Rome’s Hidden Cruelties: Disturbing facts about the Roman Empire (Part 2)

From staged executions in the arena to poisonings in the palace and children sold into sex, the Roman Empire perfected violence as a tool of order. This isn’t just history—it’s a chilling anatomy of power, control, and the brutal cost of greatness.

Rome’s greatness was built not only on engineering and empire, but on blood and fear. Beneath its triumphal arches and civic pride, the Empire maintained control through spectacle, exploitation, and silenced suffering.

In the amphitheaters, death was staged as entertainment. In politics, betrayal was sharpened with daggers and poisoned cups. In private, women and children were bought, sold, and violated with legal impunity. Even in matters of health, the façade of civilization masked practices that put lives at risk. These were not aberrations—they were Roman order, codified and glorified. This is the world behind the marble.

When Killing Became Entertainment

Across cultures and history, death is rarely ignored. It disturbs, compels, and demands acknowledgment—especially when it is public, violent, or untimely. While natural death evokes sadness or reflection, societies have often turned to unnatural death—killings that serve social, religious, or political functions.

Whether in war, ritual sacrifice, state execution, or the slaughter of animals for meat and amusement, death has long served as a tool of control. All civilizations have shaped ways of justifying it.

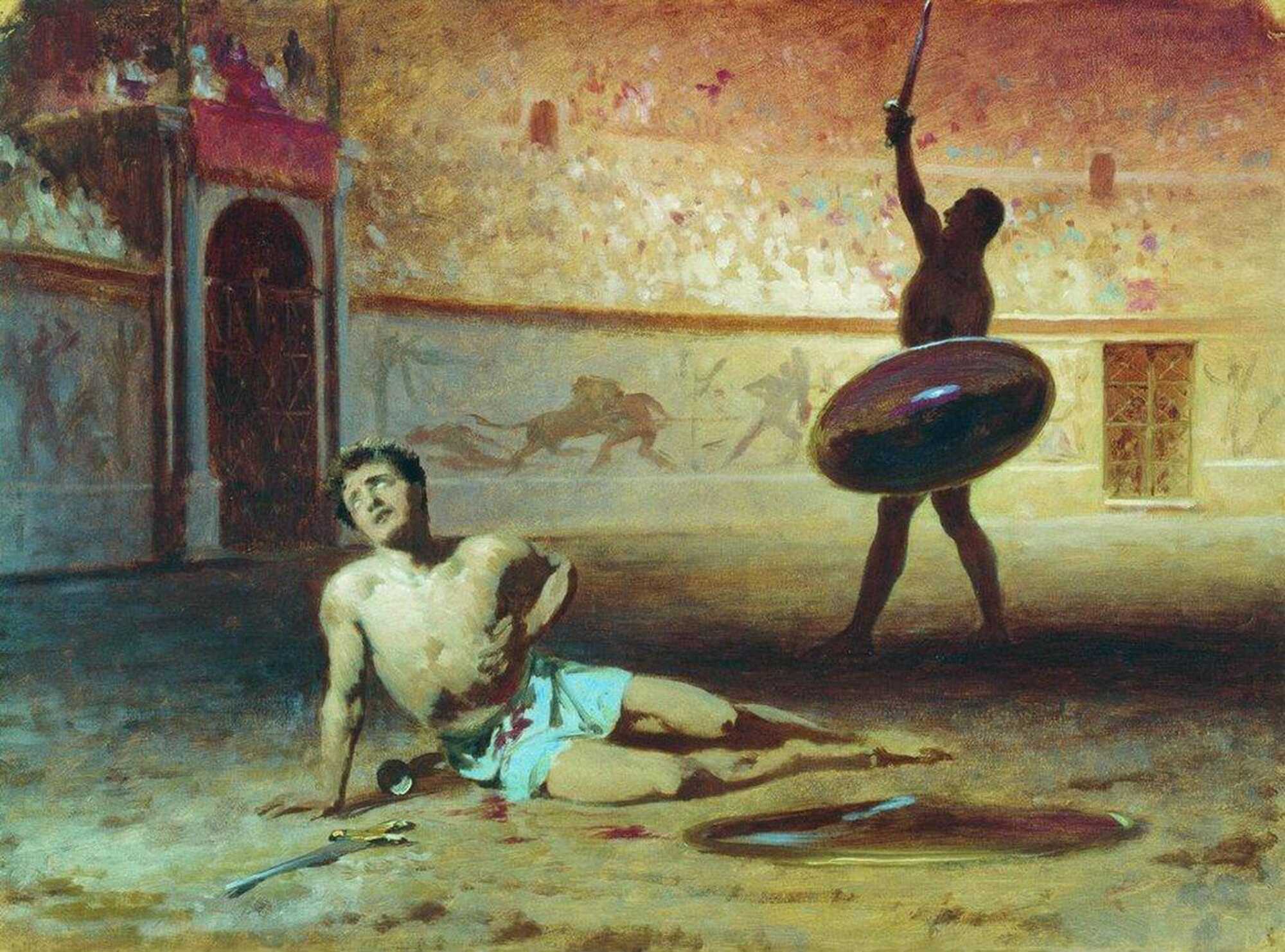

Rome, however, remains unmatched in how it elevated killing to public spectacle, applauding not just the outcome, but the style, skill, and spectacle of destruction.

A Murmillo gladiator fights a Barbary lion in the Colosseum in Rome during a condemnation of beasts, by Firmin Didot. Public domain

From early human history, killing has never been aimless—it has demanded meaning, method, and ritual. Societies surround death with customs and rites, not only to honor the dead, but to repair the community and restore order for the living.

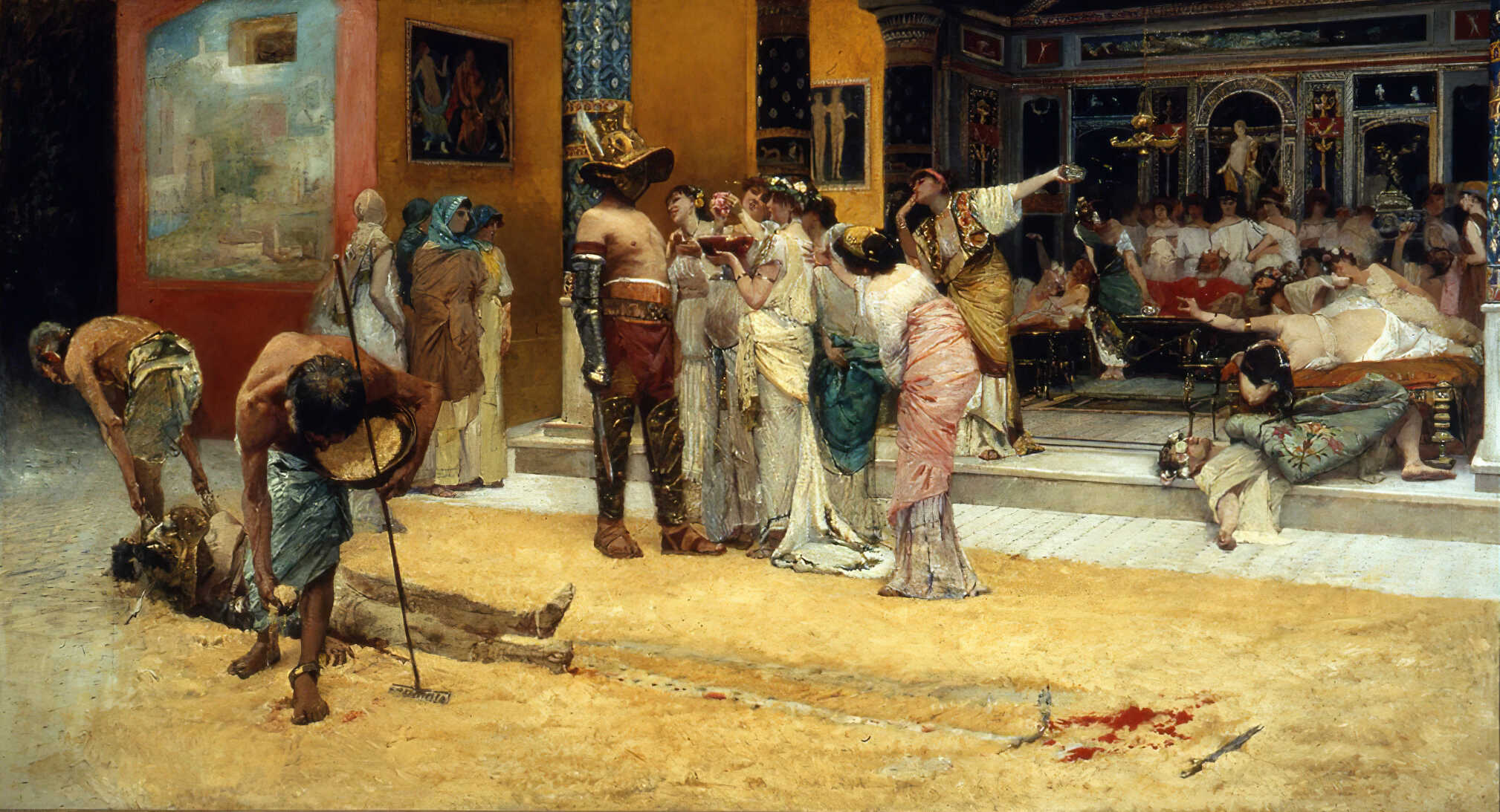

Yet in Rome, particularly under the Republic and Empire, killing moved beyond necessity into the realm of orchestrated entertainment. Gladiatorial games, beast hunts, and public executions were not merely punishments or sacrifices—they were theatrical performances, expanded and refined for mass consumption. Bloodshed became a routine part of life in the amphitheater.

The arena—spectacula as it was called in the dedication of the Pompeii amphitheater (ca. 70 BCE)—offered the public a sanctioned view of death. Romans watched criminals, prisoners, slaves, and exotic animals die as part of daily leisure.

These were not secretive or shamed acts; the killing and the killers were to be seen. The philosopher Seneca protested that the Romans had come to view the reduction of a man to a corpse as a "satisfying spectacle" (Ep. 95.33). In this culture, the transformation of death into display wasn’t an accident—it was a social function.

“Now we need swift hands, now skill must be our teacher; pleasure is sought from every direction. No vice stays within its bounds—luxury rushes headlong into greed. The memory of decency has vanished. Nothing is shameful if it can be bought. Man, who is sacred to man, is now killed for sport and amusement. The one whom it was once unthinkable to train to give and receive wounds is now brought out naked and unarmed—and a man's death is spectacle enough.”

Seneca, Moral Epistles, 95-33

Rome's violent shows were not isolated aberrations. They evolved from older traditions: sacrifices, funerals, punishments, and wartime executions. What made them distinct was the scale, ingenuity, and aestheticization of death.

Political ambition and imperial wealth fed the games, while citizens were reassured and entertained. Few societies in antiquity rivaled the scale and ritualization of Rome’s public killings—perhaps only the Aztecs and Maya approached its complexity and intensity.

In the end, Roman spectacles of death were more than brutal distractions. They reaffirmed power, glorified violence, and conditioned an entire population to see killing as normal, even pleasurable. In the architecture of Rome’s greatest venues, the seats were fixed not just toward the stage, but toward a shared reality where death became the rhythm of daily life.

The Arena and the Empire: Ritualized Violence as Social Order

Scholars across disciplines have long debated why societies ritualize violence, and Rome provides one of the most vivid—and disturbing—examples. From anthropologists to historians, many suggest that public violence reflects a deeper social need: to control, symbolically manage, or make sense of disorder, mortality, and power.

In Roman society, death was not hidden. Executions, beast hunts, and gladiatorial combat were choreographed performances, designed to be watched, remembered, and repeated.

Some theories trace these spectacles to ancient religious roots—rituals of sacrifice transformed into public shows. Others tie them to Rome’s militarism, seeing the arena as a theatrical extension of war, triumph, and conquest.

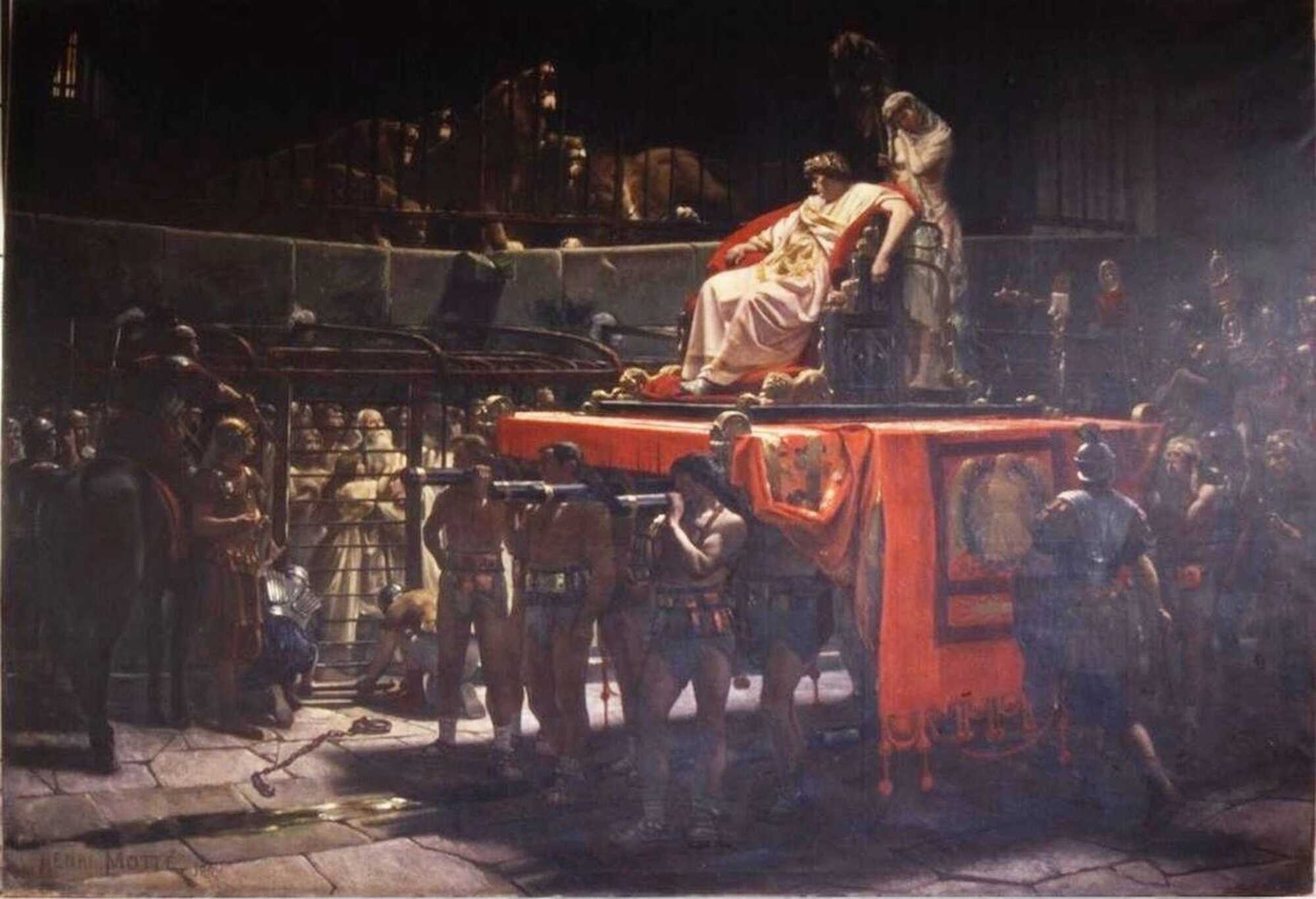

In times of peace, the blood of slaves, criminals, and animals became substitutes for foreign enemies, offering both entertainment and civic reassurance. Games were staged during festivals, imperial birthdays, and military victories, reinforcing the emperor’s role as benefactor and protector.

The arena was not just about domination from above. It was a social space, where emperors were expected to demonstrate generosity, where the crowd could express approval—or dissent—and where the Roman people collectively confronted ideas of life, death, justice, and identity.

Scholars like Thomas Wiedemann and Paul Plass view the games as liminal rituals: controlled eruptions of violence that reaffirmed social order by confronting its limits. Others, like Carlin Barton, interpret them as psychological spectacles—obsessed with monsters, deformity, and self-annihilation—as a way to purge tension and reaffirm control.

In this view, the Roman arena was a school of death and identity—a place where killing became a civic lesson. It reminded Romans who they were, who they weren’t, and who had the power to decide. (Spectacles of death in Ancient Rome, by Donald G.Kyle)

Bought Bodies: The Lives of Roman Prostitutes and Sex Slaves

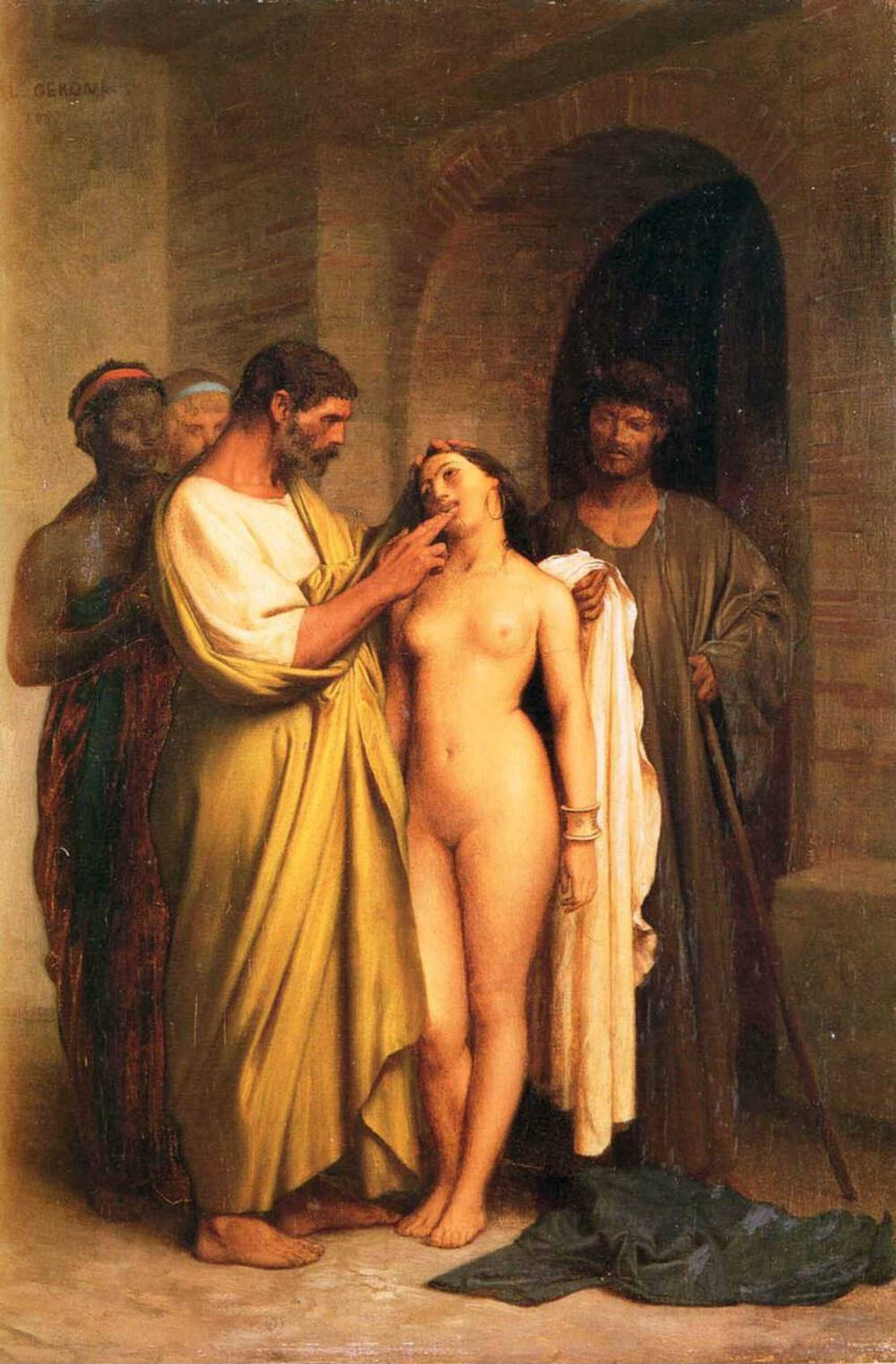

The figure of the enslaved or captive woman forced into prostitution has often been romanticized in Roman literature, but graffiti, legal texts, and epigraphic evidence tell a far grimmer story.

In Pompeii, many graffiti openly advertise girls identified as vernae—slaves born in the household—offering their services for a few coins. The fact that their status as homeborn is emphasized suggests that it was considered a selling point, pointing to a broader norm: that enslaved people, especially women, were routinely prostituted by their owners.

Some scholars argue that for many enslaved women, sex work was considered a form of domestic labor, especially when it took place within the household. Graffiti found near the entrances of private homes suggest that enslaved prostitutes may have received clients in their owners' residences.

In contrast, the literary figure of the full-time brothel prostitute is largely the creation of elite male authors, while historical evidence shows that sex work for many Roman women—free or enslaved—was occasional, coerced, or circumstantial.

The Silent Entry of Children into the Trade

Legal texts reveal the long shadow cast by prostitution on a woman’s legal and social status. For example, the jurist Modestinus wrote that cohabiting with a free woman should be considered marriage, unless she had been a prostitute. This shows how deeply prostitution stigmatized women, making even their personal relationships legally suspect.

Sex work was not confined to brothels. Roman sources frequently associate prostitution with baths, taverns, theaters, and markets, and entertainers like dancers and actresses were often conflated with prostitutes. Whether they sold sex or were merely sexualized by association, they shared in the same cultural marginalization.

Disturbingly, Roman sources also reveal that many prostitutes entered the trade as children. Seneca refers to fathers forced by poverty to hand over their children to prostitution with their own hands, and Roman plays and epigrams echo this trope—abandoned or impoverished children raised for profit by brothel owners.

While some literary sources condemned the prostitution of freeborn children as immoral, there were no laws prohibiting it.

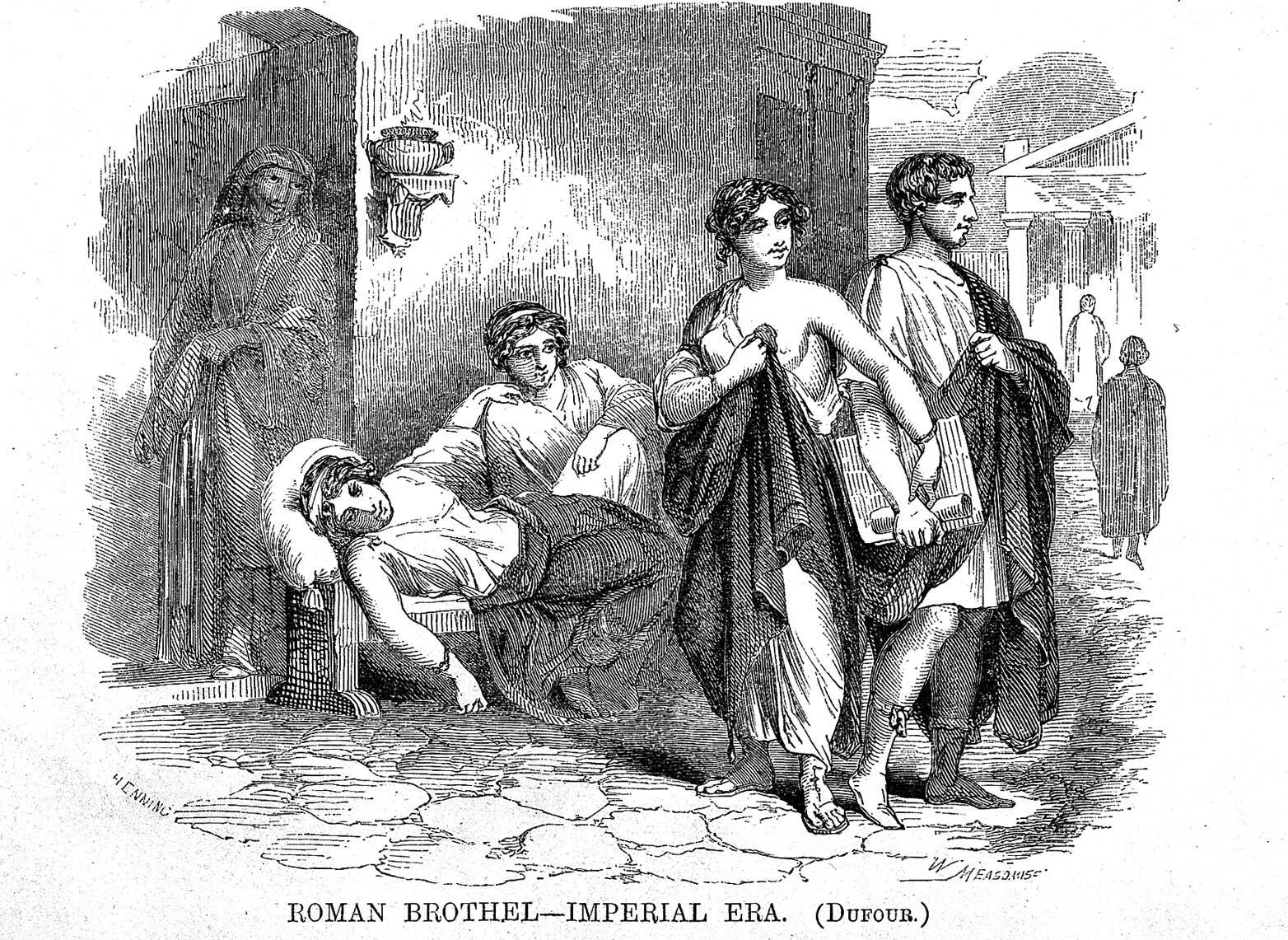

A gravure depicting a Roman Brothel in the Imperial Era. Credits: Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0

Children, like slaves, were treated as property.

“Deny now that nature has bestowed a great benefit by making death necessary.

Many are prepared to make even worse bargains: to betray a friend so they might live longer, or to hand over their children to sexual abuse with their own hands, just to see the light of day—a light that bears witness to so many of their crimes.

We must shake off our desire for life and learn that it makes no difference when we endure what must be endured eventually.”

Seneca, Moral Epistles, 101.14–15

It’s also important to note that a significant number of Roman prostitutes were male. Despite later claims that same-sex prostitution was a foreign import, Roman sources attest that boys were freely prostituted and even honored in the calendar—April 25 was marked out for pueri leonii, “the pimp’s boys.” These youths, expected to serve male clients passively, were just as much a part of Rome’s exploitative system.

Whether any sex workers served female clients is uncertain. Juvenal jokes about women lavishing gifts on pretty-boy lovers, but his intent is satire, not documentation. Even graffiti like “Glyco licks c*nt for 2 as*es” leaves modern readers unsure—was it a real transaction, a boast, or a slur? What is clear is that sex in Rome was deeply entangled with power, status, and survival, and those with the least of all three paid the highest price. (Women in antiquity, edited by Stephanie Lynn Budin and Jean Macintosh Turfa)

The Overlooked Victims: Child Sexual Exploitation in Ancient Rome

Children in ancient Rome, especially those enslaved or born into poverty, were among the most vulnerable members of society. While Roman literature often romanticized or obscured the realities of youth, inscriptions and legal ambiguities suggest that the line between childhood and commodification was dangerously thin.

As aforementioned, graffiti from Pompeii openly advertise girls identified as vernae—slaves born in the household—offering sexual services for a few coins. Their homeborn status was treated as a mark of value, suggesting that enslaved minors were routinely prostituted by their owners. Many of these inscriptions appear not in brothels but near the entrances of private homes, indicating that such acts often occurred within domestic spaces. (The Economy of Prostitution in the Roman World, by Thomas A. J. McGinn)

Although Roman moralists occasionally condemned the prostitution of freeborn children, no laws prohibited it—especially when the child was under the legal authority (patria potestas) of the father. Children, like slaves, were considered part of the household’s property, and their use for profit, including sexual exploitation, was largely unrestricted. (Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian, by Susan Treggiari)

The literary tradition reinforces this troubling norm. In Cistellaria, Plautus presents a girl raised in a brothel after being abandoned as a baby, and Martial’s epigrams echo the theme of impoverished or discarded children raised for sexual use. These recurring motifs reflect a cultural familiarity with the idea that children could be commodified through the sex trade. (from Plautus, Cistellaria 38–40 and Martial, Epigrams 9.5.6–9; discussed in “Medicine and the Making of Roman Women” by Rebecca Flemming)

Male children were also exploited. Like we underlined above, the Fasti Praenestini, a Roman calendar inscription, assigns April 25 to the pueri lenonii—“the pimp’s boys”—indicating institutional acknowledgment of their role. Servius, in his commentary on Vergil’s Eclogues, affirms that Romans had long used boy prostitutes, contradicting the idea that the practice was a Greek import. (from the Fasti Praenestini (CIL I² 236) and Servius, ad Ecl. 8.29; analyzed in “Roman Homosexuality” by Craig A. Williams)

In Rome’s sex economy, children were not spared. They were groomed, advertised, bought, sold, and used—often in spaces considered respectable, and with few voices raised in their defense. The absence of legal protection, combined with economic desperation and cultural indifference, left them exposed to the cruelest fates in a society that codified hierarchy in both law and flesh.

Power in the Shadows: Political Assassinations and Poisonings in the Roman Empire

In ancient Rome, power was rarely secure—and death was often the price of ambition. Political assassinations and poisonings were not aberrations; they were tools of the statecraft, practiced as ruthlessly in palaces as they were whispered about in the streets. Behind every imperial succession lay a story of betrayal, ambition, or opportunistic removal.

The murder of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March 44 BCE was not the first such act in Roman history, but it became the most iconic. His stabbing in the Senate was carried out not by outsiders but by senators—many of them his own allies—who claimed to be defending the Republic. Yet far from restoring order, Caesar’s death opened the floodgates to a new age of imperial intrigue where conspiracies flourished and poison became a political weapon. (The Death of Caesar, by Barry Strauss)

From the first emperors onward, poison was regarded as the most insidious form of political murder. The feared female poisoner Locusta was employed by Agrippina the Younger—mother of Nero—who, according to Tacitus, orchestrated the poisoning of her husband Emperor Claudius to elevate her son. Locusta also reportedly crafted the fatal draught used by Nero to eliminate his stepbrother Britannicus. (Agrippina: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Early Empire, by Anthony A. Barrett)

“Under this great burden of anxiety, he had an attack of illness, and went to Sinuessa to recruit his strength with its balmy climate and salubrious waters.

Thereupon, Agrippina, who had long decided on the crime and eagerly grasped at the opportunity thus offered, and did not lack instruments, deliberated on the nature of the poison to be used.

The deed would be betrayed by one that was sudden and instantaneous, while if she chose a slow and lingering poison, there was a fear that Claudius, when near his end, might, on detecting the treachery, return to his love for his son.

She decided on some rare compound which might derange his mind and delay death.

A person skilled in such matters was selected, Locusta by name, who had lately been condemned for poisoning, and had long been retained as one of the tools of despotism.

By this woman's art the poison was prepared, and it was to be administered by an eunuch, Halotus, who was accustomed to bring in and taste the dishes.”

Tacitus, Annales, 12.66–67

“He began the practice of parricide and murder with Claudius himself; for although he was not the contriver of his death, he was privy to the plot.

Nor did he make any secret of it; but used afterwards to commend, in a Greek proverb, mushrooms as food fit for the gods, because Claudius had been poisoned with them.

He traduced his memory, both by word and deed in the grossest manner; one while charging him with folly, another while with cruelty.

For he used to say by way off jest, that he had ceased morari amongst men, pronouncing the first syllable long; and treated as null many of his decrees and ordinances, as made by a doting old blockhead.

He enclosed the place where his body was burnt with only a low wall of rough masonry.

He attempted to poison Britannicus, as much out of envy because he had a sweeter voice, as from apprehension of what might ensue from the respect which the people entertained for his father's memory.

He employed for this purpose a woman named Locusta who had been a witness against some persons guilty of like practices.

But the poison she gave him, working more slowly than he expected, and only causing a purge, he sent for the woman, and beat her with his own hand, charging her with administering an antidote instead of poison; and upon her alleging in excuse, that she had given Britannicus but a gentle mixture in order to prevent suspicion, "Think you," said he, " that I am afraid of the Julian law;" and obliged her to prepare, in his own chamber and before his eyes, as quick and strong a dose as possible.

This he tried upon a kid: but the animal lingering for five hours before it expired, he ordered her to go' to work again; and when she had done, he gave the poison to a slave, who dying immediately, he commanded the poison to be brought into the eating-room and given to Britannicus, while he was at supper with him.

The prince had no sooner tasted it than he sunk on the floor, Nero meanwhile pretending to the guests, that it was only a fit of the falling sickness, to which, he said, he was subject.

He buried him the following day, in a mean and hurried way, during violent storms of rain.

He gave Locusta a pardon, and rewarded her with a great estate in land, placing some disciples with her, to be instructed in her trade.”

Suetonius, Nero, 33

The image of poison as a “woman’s weapon” was often invoked in elite Roman discourse, not to reflect biological reality, but to moralize about power wielded from the shadows. In practice, both men and women used poison. It was ideal for eliminating rivals discreetly in an age where even suspicion could ruin reputations.

The Praetorian Guard, who were sworn to protect emperors, often played a double role—as bodyguards and assassins. It was they who killed Caligula in 41 CE and then, decades later, struck down the tyrant Domitian in his own palace. Suetonius recounts the conspiracy against Caligula, highlighting the involvement of the Praetorian Guard:

"Such frantic and reckless behaviour roused murderous thoughts in certain minds.

One or two plots for his assassination were discovered; others were still awaiting a favorable opportunity, when two men put their heads together and succeeded in killing him, thanks to the co-operation of his most powerful freedmen and the Guards' commanders.

These commanders had been accused of being implicated in a previous plot and, although innocent, realized that Gaius hated and feared them."

Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum, Caligula 56

In describing Domitian's assassination, Suetonius notes the role of Stephanus, a steward, in the plot:

"Concerning the nature of the plot and the manner of his death, this is about all that became known.

As the conspirators were deliberating when and how to attack him, whether at the bath or at dinner, Stephanus, Domitilla's steward, at the time under accusation for embezzlement, offered his aid and counsel.

To avoid suspicion, he wrapped up his left arm in woollen bandages for some days, pretending that he had injured it, and concealed in them a dagger."

Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Domitian 17

Cassius Dio provides an account of a macabre banquet hosted by Domitian, reflecting the emperor's tyrannical nature:

"After this all the things that are commonly offered at the sacrifices to departed spirits were likewise set before the guests, all of them black and in dishes of a similar colour.

Consequently, every single one of the guests feared and trembled and was kept in constant expectation of having his throat cut the next moment, the more so as on the part of everybody but Domitian there was dead silence, as if they were already in the realms of the dead, and the emperor himself conversed only upon topics relating to death and slaughter."

Cassius Dio, Historia Romana, 67.15

Historians have noted how poisonings and assassinations were rarely about personal vendettas. Instead, they were strategies embedded in the political machinery of the Empire.

Tiberius and Nero alike used "forced suicide" as a method to eliminate senators and generals under the guise of propriety. Victims were given the choice to die “with dignity” or face public disgrace and execution. This theatre of death served the state—it neutralized threats while maintaining a façade of lawful conduct.(Nero: The End of a Dynasty, by Miriam Griffin and Tacitus, Annals 6.19)

The weaponization of poison extended beyond the palace. Roman texts describe herbs, powders, and slow-acting toxins used not only to murder but to manipulate wills, sabotage pregnancies, or cripple political adversaries. The Lex Cornelia de Sicariis et Veneficiis (Cornelian Law on Murderers and Poisoners) shows how deeply the state was concerned with such practices—and how often it failed to stop them. (The Criminal Law of Ancient Rome, by Olivia Robinson)

In this environment, paranoia was not a flaw—it was a survival strategy. Senators were cautious about their dinner hosts; emperors obsessed over tasters and trusted no one. Suetonius tells of Domitian lining palace walls with polished stone so he could watch behind him. (Suetonius, Domitian 14)

Assassination was not merely political—it became symbolic. Removing a ruler often came with ritualistic overtones: stabbed in the heart of power, poisoned at the imperial banquet, or forced to open their veins in the Roman bath. The deaths were messages. Each body silenced was also a sign to others. In Rome, to live close to power, was to live close to death.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: