Suetonius: The Faceless Scholar of Imperial Rome

Suetonius' influence extends beyond his own time. His biographical style set a precedent for later historians and biographers.

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, was a Roman historian and biographer, best known for his work The Twelve Caesars (De Vita Caesarum), which provides detailed biographies of the first twelve Roman emperors, from Julius Caesar to Domitian.

Who was the pen that shaped Roman history?

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus is one of the many Roman writers who reveal little about their personal lives. He mentions only that he was the son of Suetonius Laetus, a Roman knight who served as a tribune in the thirteenth legion during the battle of Betriacum.

Apart from four other brief references, which don’t add much but help estimate his birth year—placed by Mommsen, a renowned 19th-century German scholar, in 77 CE, and by Macé, an American historian, more likely in 69 CE—we know little about his early life. Most of what we know comes from the letters of Pliny the Younger and a single reference in Spartianus, who wrote a biography of Hadrian during the reign of Diocletian.

Suetonius' birthplace is unknown, though he may have been one of the few Roman writers actually born in Rome. The date of his death is also uncertain; the last reference to him is in 121 CE, but the extent of his works and an implication in one of Pliny’s letters that he was slow to publish suggest that he lived to an old age, possibly into the reign of Antoninus Pius.

One of the greatest mysteries is his physical appearance, as no records or busts exist from the Roman times

A 19th-century etching of Suetonius, of questionable accuracy. Public domain

Pliny notes that Suetonius briefly practiced law, though not for long. The claim that he was a schoolmaster, made by Macé and others, lacks solid evidence. Suetonius did not engage in political life, and although he secured a military tribuneship with Pliny's help, he soon passed it on to a relative.

He received the jus trium liberorum (the right to have three children) from Trajan, although he apparently had no children, and there’s no evidence to support claims that his marriage was unhappy. The fact that Trajan granted him this privilege, despite being reluctant to do so for those who didn’t legally qualify, might indicate Suetonius’ high character.

Pliny’s letters refer to Suetonius as contubernalis (comrade), indicating a close friendship and similar age, though Pliny’s higher status might account for some differences. Pliny’s correspondence mentioning Suetonius spans from around 96 to 112 CE.

Spartianus (Aelius Spartianus, was one of the authors associated with the Historia Augusta, a collection of biographies of Roman emperors, usurpers, and other notable figures from the reign of Hadrian to that of Numerian), informs us that Suetonius served as a secretary to Emperor Hadrian, likely during the time when his friend and patron, Gaius Septicius Clarus, was the prefect of the Praetorian Guard (from 119 to 121 CE).

Spartianus also notes that both Suetonius and Septicius were dismissed by Hadrian for a breach of court etiquette rather than any serious misconduct. After this event, Suetonius fades from the historical record, and it is likely that he retired and focused on his literary pursuits.

The works of Suetonius

There are numerous references to Suetonius' works, with a catalog of them preserved by Suidas, supplemented by information from other sources. Suetonius was a scholar with a wide range of interests, and in keeping with the trends of his later years, he appears to have written in both Greek and Latin. His writings covered various subjects, including history (particularly biography), antiquities, natural history, and grammar.

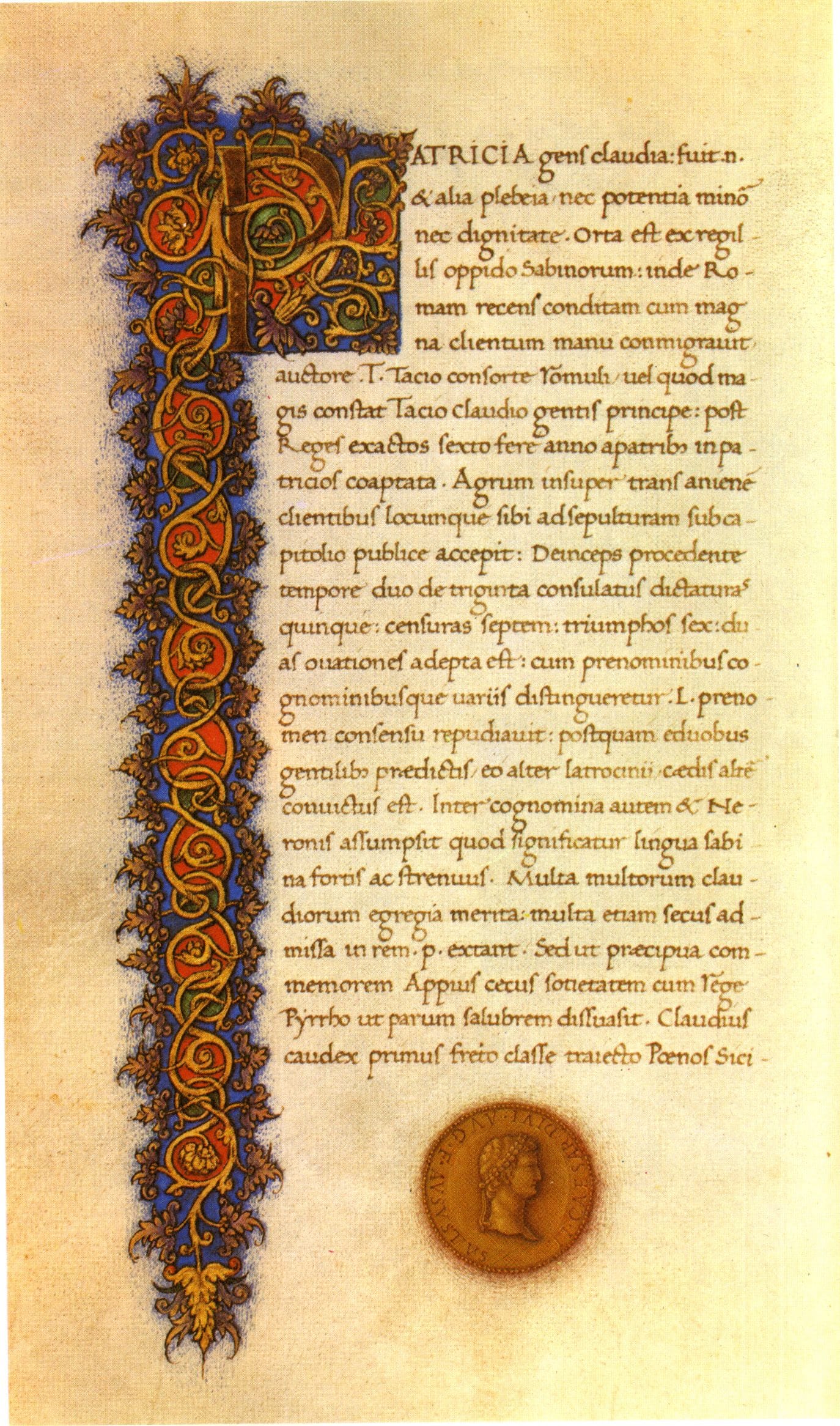

The only complete, or nearly complete, work of Suetonius that has survived is The Lives of the Caesars, published in 120 CE. This collection, as aforementioned, includes the biographies of twelve emperors, from Julius Caesar to Domitian. Although it is largely intact, it is missing the first few chapters of Julius Caesar's life, and there are a few minor gaps. According to Johannes Lydus, a sixth-century writer, he had access to a manuscript that included a dedication to Septicius Clarus, which likely contained the missing portion about Julius.

This section must have been lost sometime between the sixth and early ninth centuries.

Suetonius countless works lost in time. Illustration: Midjourney

Suetonius' extensive body of work earned him lasting fame, and later writers in various fields frequently used his writings as sources. As a result, many excerpts from his lost works and the missing sections of De Viris Illustribus have been preserved. Historical writers like Eutropius, Aurelius Victor, and Orosius often borrowed directly from Suetonius, sometimes reproducing his exact language, which helps in analyzing his text.

Suetonius significantly influenced the style of historical writing, steering it towards a biographical focus for several centuries. He inspired imitators and successors, such as Marius Maximus, whose works have not survived, and the authors of the Augustan History (Scriptores Historiae Augustae), whose biographies have.

His influence extended to Christian writers, evident in the Life of Ambrosius by Paulinus, Ambrosius' secretary, and even reached the Middle Ages, where Einhard modeled his Life of Charles the Great on Suetonius' style, possibly using a manuscript related to those that have survived to the present. (Suetonius. With an English translation by J. C. Rolfe, PhD, Professor of the Latin language and literature in the University of Pennsylvania)

The Historian and His Emperors: Analysis of Lives of the Caesars

Suetonius' De Vita Caesarum was published around the time of Emperor Hadrian's accession in AD 117, though the exact date is uncertain. The preface included a dedication to Septicius Clarus, one of Hadrian's praetorian prefects, suggesting that Suetonius was still serving as ab epistulis (a chancellor responsible for the emperor's correspondence) when the work was written.

The eight volumes may have been released gradually over a decade, and it's unclear when Suetonius began writing. It's also possible that Roman audiences had a preview of the Caesars through literary recitations before its official publication.

The work was daring, as it covered the lives of twelve Caesars. Suetonius chose to stop at Domitian, as the strong ties between the reigning emperor Hadrian, Nerva, and Trajan would have necessitated a more flattering portrayal, which wasn't Suetonius' intention. His endeavor was bold, given that Tacitus, a towering figure in Roman historiography, had recently covered the same period in his Histories and Annals.

Suetonius was aware of Tacitus' influence but approached his work differently, focusing on biographical sketches rather than historical narratives. This allowed him to minimize direct overlap with Tacitus' works. While Tacitus was a dominant figure, Suetonius established his own distinct foundation in literature, with a different intellectual approach than that of the historian, former consul, and orator.

Suetonius deliberately chose not to write history in the traditional sense; instead, he focused on scholarship. This choice should not be seen as a mistake. Suetonius’ deliberate avoidance of what were considered historical techniques in ancient times was not just a side effect of his scholarly approach—it was central to his work.

By distancing his biographies from traditional history, especially when dealing with historical material, Suetonius asserted the independence of his genre. His approach to the Caesars was, in many ways, a deliberate inversion of historical methods. The three key aspects that defined history for the ancients—structure, subject-matter, and style—are precisely where Suetonius chose to emphasize his role as a scholar rather than a historian. (Suetonius, the scholar and his Caesars by Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew)

Suetonius' Lives of the Caesars is a work that is not as well-known as it should be. Despite its frequent citation in historical writings and treatises on Roman antiquities, this statement holds true due to its limited presence in college curricula and the scarcity of English editions of the Caesars or individual lives.

Additionally, there is no comprehensive and satisfactory commentary available in any language. Suetonius' style reflects that of an investigator and scholar, focusing on clarity rather than rhetorical flourish or dramatic effect. Unlike the popular styles of his time, such as the one favored by Seneca or the archaic style that later gained popularity, Suetonius preferred a straightforward approach.

His style, as he describes Augustus' writing, is accurate, forceful, and concise, often packing his sentences with meaning. Occasionally, he produces phrases reminiscent of Tacitus, though these seem to stem more from his subject matter than from any deliberate stylistic choice.

Suetonius had access to an extensive array of sources, many of which are now lost to us, including historical works, memoirs, public records, documents, and private correspondence, both published and unpublished. His close relationship with Pliny the Younger provided him with insights into senatorial opinions, and his position under Emperor Hadrian gave him access to imperial archives, possibly through his colleague ab studiis.

Few individuals had such rich opportunities for research, and Suetonius was as diligent a collector of material as the elder Pliny.

Suetonius’ office, filled with materials of study. Illustration: Midjourney

Although he made limited use of inscriptions, which are highly valued today, this was likely due to the abundance of literary sources available to him and the specific focus of his work. However, he did occasionally reference inscriptions and demonstrated an understanding of their importance.

In general, Suetonius' approach is more that of a scholar and researcher than that of an inquirer or observer. He diligently searches through records but seldom includes hearsay or personal observations, whether from his grandfather, others of an earlier time, or his own experiences.

His primary interest lay in collecting entertaining anecdotes and details about personalities, which he drew from various sources indiscriminately. He either didn’t recognize or expected his readers to discern that unbiased opinions about Augustus were unlikely to be found in the letters and speeches of Mark Antony, or that not all historians were equally reliable.

As a result, none of the Caesars come across as particularly heroic in Suetonius' accounts. Julius Caesar, for instance, is depicted as a ruthless politician who sought supreme power from an early age and was willing to use any means to achieve it. Despite acknowledging Caesar's moderate use of his victory and his many plans for the state's welfare, Suetonius seems to believe that Caesar ultimately deserved his assassination.

While Suetonius shows some admiration for Augustus and Titus, he does not shy away from documenting Augustus' calculated cruelty and seduction or Titus' violence, debauchery, and shameless greed. In fact, Suetonius is so thorough that he even records accusations he himself does not fully believe.

On the other hand, he dutifully lists the good deeds and qualities of emperors like Tiberius, Caligula, Nero, and Domitian, despite clearly holding an unfavorable view of them overall. Vespasian is portrayed most favorably, with his only fault being stinginess, which Suetonius tends to justify as a necessity.

Vespasian's story is one of the most dramatic in the series, depicting a practical, humorous man driven to seek political office only by his mother's taunts, and who maintained his simple habits and common sense even after becoming emperor.

Suetonius recounts various episodes from Vespasian's life, such as when he offended Nero by falling asleep or leaving the theater during the emperor's performance, was pelted with turnips in Hadrumetum, and was smeared with mud on Caligula's orders for neglecting his duties—punishments Suetonius attributes to the mad genius of Caligula.

Despite Vespasian's fears of Nero's vengeance, the opportunity arose for him during the war in Judaea, where his energy and ability as a leader, proven in Britain under Claudius, made him the right choice. Upon becoming emperor, Vespasian gained the necessary prestige and sanctity by performing miracles, yet his humility remained intact, as shown by his deathbed joke, "Woe's me! Me thinks I'm turning into a god."

Suetonius concludes with a powerful image of the determined old man struggling to meet death standing, as an emperor should, dying in the arms of his attendants.

Although Suetonius likely intended his approach to be impartial, and while it might have been closer to impartiality in the hands of a more critical writer, his method does not provide a balanced evaluation of the emperors.

To understand this, one only needs to imagine a biography of a contemporary figure composed of praise and criticism taken indiscriminately from both supporters and opponents, presented with little or no commentary. (Suetonius and His Biographies by John C. Rolfe)

As John C. Rolfe states,

“While it is obvious that we must regard the "Lives of the Caesars" more or less in the light of a work of fiction, it deserves to be read as our best and most characteristic specimen of Roman biography albeit with an open mind and in a spirit of scholarly scepticism.”

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: