Tacitus: The Chronicler of Rome’s Moral Decline

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, commonly known as Tacitus, was a Roman historian and politician. He is widely considered one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

Who was Tacitus?

Publius Cornelius Tacitus was born around 54 A.D., the year Nero began his reign. He studied under Quintilian, the first Regius Professor of Rhetoric, and trained for the bar under the skilled jurists Aper and Secundus. In 77 or 78, he married the daughter of the notable general Agricola.

Tacitus progressed in his political career, becoming quaestor in 81, praetor in 88, and consul in 97. Between the latter dates, he was likely absent from Rome for four years, possibly serving as governor of a less significant province. In 112, his career peaked with his appointment as Proconsul of Asia, the highest position a private individual could achieve under the Empire. He died in 117.

His lifetime spanned the reigns of Nero, the tumultuous year of Galba, Otho, and Vitellius, the Flavian dynasty (Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian), and the prosperous era of Nerva and Trajan. Tacitus was a skilled lawyer, competent administrator, and distinguished public figure. His extensive experience parallels that of historians like Thucydides, Cromer, and Macaulay, rather than Herodotus, Livy, and Grote. (Tacitus the historian by By Louis E. Lord, Oberlin College)

Tacitus' Personal Life

Details about the personal life of Tacitus are limited. The little that is known comes from hints scattered throughout his works, the letters of his friend and admirer Pliny the Younger, and an inscription found at Mylasa in Caria.

Tacitus was likely born in northern Italy (Cisalpine Gaul) or more probably in southern Gaul (Gallia Narbonensis, present-day southeastern France). His parentage remains unknown. While "Cornelius" was a name associated with a noble Roman family, there is no evidence suggesting he was descended from the Roman aristocracy; provincial families often adopted the name of the governor who granted them Roman citizenship.

Despite this, Tacitus grew up in comfortable circumstances, received a good education, and had a clear path to a public career.

The Roman world underwent significant changes during Tacitus' lifetime (A.D. 55-117) and the preceding century. These changes profoundly transformed Roman institutions, social classes, civic roles, and character. The transition from the Republic to the Empire, particularly the years Tacitus chose to describe, was marked by numerous horrors, crimes, and periods of terror.

This turbulent experience, rather than his studies, led Tacitus to develop a philosophy centered on survival. However, mere survival was insufficient for the grand moral purpose of Roman historical writing. Despite being a Roman senator in an imperial era, Tacitus remained committed to republican and senatorial standards, the criteria by which he judged the formative period of his new age.

He eventually found himself caught between two worlds: the imperial world of his maturity, where he developed his survival philosophy, and his continued dedication to serving Rome.

Tacitus studied rhetoric in Rome, and his rhetorical and oratorical skills are evident throughout his significant works, the incomplete but noteworthy Annals and Histories. Written in elegant, unmatched Latin prose, marked by often bitter and ironic observations on the human tendency to abuse power, Tacitus traces the violent path of the Roman Empire from the death of Augustus in 14 CE to the end of Domitian's reign in 96.

The work of Tacitus and its significance

Cornelius Tacitus, is one of the most valuable sources for early Roman Empire history. His commanding style is unmatched, his narratives are complex, and his speeches showcase remarkable rhetoric and metahistory. Tacitus' historical accounts are deeply intertwined with his views on human nature, and his prose carries a palpable sense of survivor’s guilt.

He vividly portrays the tensions between individuals and society, particularly in the strained relationships between emperors and senators, generals and soldiers, governors and provincials, and within family dynamics such as uncle and nephew, mother and son, and husband and wife. Though his writing is concise, his messages are clear, and his condemnation of those who fail to meet his high moral standards is filled with a barely concealed anger.

Tacitus‘ Five Surviving Works

- The Life of Julius Agricola, a biography of his father-in-law, who was governor of Britannia under Domitian.

- Germania, a brief treatise on the customs and peoples of Germania.

- The Dialogue on Orators, a discussion among friends about the importance and decline of public speaking.

- The Histories, of which only the first five books survive, recounts the tumultuous year 69 AD when four emperors—Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian—ruled Rome, with Vespasian founding the Flavian dynasty.

- The Annals, which chronicle the Julio-Claudian emperors, covering Tiberius' reign in Books 1–4 and fragments of Books 5 and 6. The entire reign of Caligula is missing due to gaps between Books 6 and 11. Books 11–12 cover the end of Claudius' reign, and Books 13–16 cover Nero's reign. The manuscript of The Annals breaks off in the middle of Book 16. (Tacitus by Victoria Emma Pagan, Professor of Classics at the University of Florida)

Tacitus’ Influence in Modern History

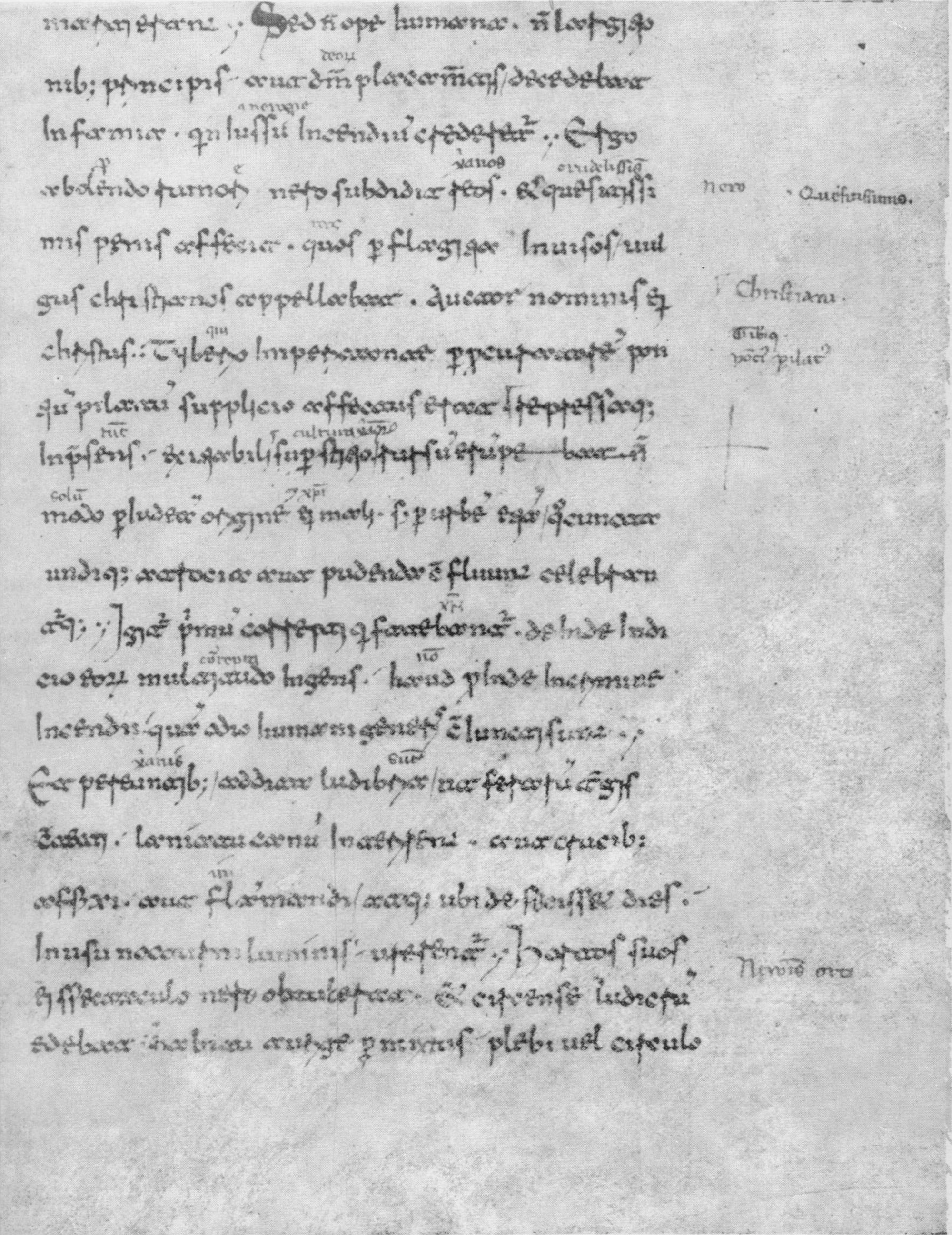

In classical antiquity, there are only sporadic references to Tacitus' works, partly due to the accidents of transmission. Tacitus seems to have been overlooked during late antiquity and the Middle Ages (650–850 CE).

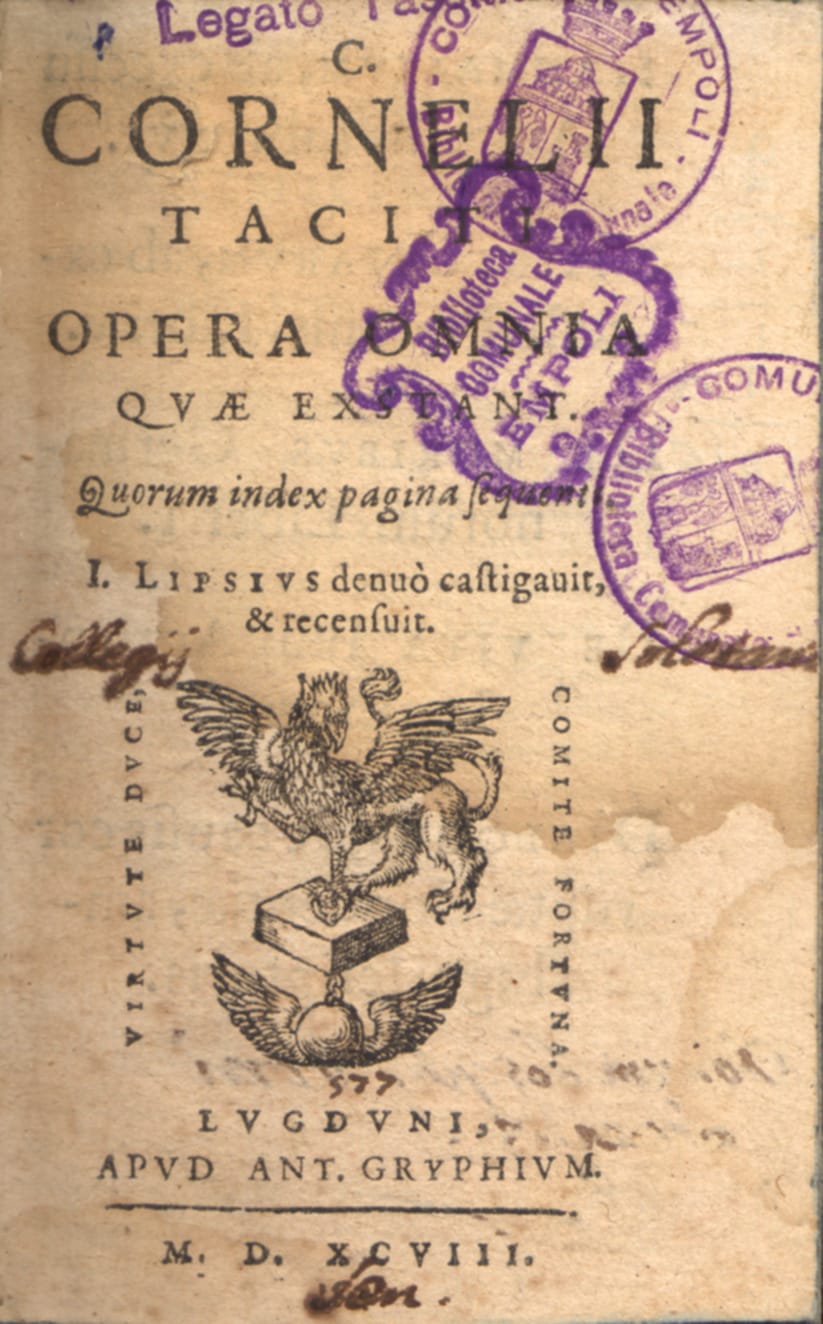

By 1362, the Florentine scholar and poet Giovanni Boccaccio was reading Annals Books 11–16 and Histories Books 1–5; by 1473, a first edition of Germania and Dialogue on Orators appeared in Venice. The publication of Annals Books 1–6 and Agricola in 1515 during the Renaissance age of Niccolò Machiavelli marked a significant revival of Tacitus' works.

In the sixteenth century, 45 editions of his work were published, including the monumental edition by the Flemish philologist Justus Lipsius in 1574, and 103 more editions appeared in the seventeenth century. Between 1580 and 1700, 100 commentaries on Tacitus' works were published.

The eighteenth century was known as the age of Tacitism in Britain, and the nineteenth century in Germany. Tacitus' political thought had a profound impact on European intellectual history and beyond. Recent scholarship by Christopher Krebs on the influence of Germania in early to mid-twentieth-century Germany illustrates the strong hold Tacitus had on the imagination of the emerging German nation.

Postwar German artist Anselm Kiefer and American poet Frank Bidart have drawn inspiration from Tacitus for works that confront and attempt to heal the traumas of World War II. In 1983, American historian Stanley Karnow began his Vietnam: A History, with one of Tacitus' most famous quotes: “They make a wasteland and call it peace.”

The influence of Tacitus on Western thought is profound and enduring. Studying Tacitus opens a window into the captivating world of Roman politics, history, and private life that he recreated in his writings. For instance, Tacitus vividly describes the Capitol consumed by flames, and although the fire was accidental, readers can still feel the hollow senselessness of civil war.

Tacitus versus other Historians

Among all writers, both ancient and modern, Tacitus stands out as one of the most incisive and critical. His intent was to delve deeply into and reveal the hidden truths about individuals and governments.

As Victoria Emma Pagan states: “The first sentence of the Agricola prefigures a major theme that recurs in all of Tacitus’ works – the disconnect between honourable men and the dishonourable times in which they live:”

“To hand down to posterity the deeds and characters of famous men is an ancient practice neglected not even in our times (although our age is careless of its own men) whenever some great and noteworthy virtue prevailed and rose above the vice common to states great and small, namely ignorance of and hostility towards righteousness”

Tacitus, Agricola

To better understand Tacitus’ character and moral stand, one has only to see his prefaces, because it is there, he announces that he will tell the truth in a way that will benefit the community.

Other Roman historians are more forthcoming in their prefaces. For example, Sallust, (an historian and politician of the Roman Republic) through extensive introductions, reveals some of his ambitions and grievances, although much remains inferred.

Livy, a more transparent writer, openly expresses nostalgia for the past and a patriot's concern for the present. He admires Roman power and remains loyal to the ideals of an earlier Rome. Tacitus, on the other hand, reveals very little.

His prefaces are grand and formal, valued for their brevity, precision, and impersonal tone. In a passage from the Annals, he declares a moral purpose, stating that history should commemorate virtue and condemn vice eternally. While he acknowledges this as the primary function of history, other motivations likely influenced his writing, including ambition, curiosity, artistic sense, and a reaction against the stagnation or mediocrity of his age. There may also be deeper, personal reasons at play. (Syme Ronald, Who was Tacitus? Harvard Library Bulletin XI)

Tacitus’ Distinctive Style

Various aspects have been inferred from his writings. He was not just serious, but also stern and austere, averse to gaiety, and completely lacking in a sense of humor. He wasn't merely a devotee of the past but also conservative and reactionary, constantly longing for the old Republic. He was an unmistakable snob and indeed a member of the Roman aristocracy, descending from the ancient and patrician Cornelii family.

When Tacitus reflected on the court life under the Julian and Claudian Caesars, he might have felt a peculiar fascination. That era was marked by luxury, vice, and vulgarity, yet it also exhibited a gaiety and wit that had since vanished from Rome. Writing at the end of Trajan's reign and under Hadrian, Tacitus observed that current standards were more sober and wholesome.

Solid virtues held the forefront of Roman society, and there was a mediocrity that effortlessly avoided the stigma of cleverness. The upper classes were enthusiastically or reverently turning to philosophy, seeking edification through old myths reinterpreted for comfort and hope. Traditional pieties saw a revival as archaism became fashionable. This shift led to a certain dreariness, and the political landscape had changed. The men of noble birth or bravery, who had once made doctrines seem dangerous, were no longer present.

When Tacitus reflects on the past, he expresses a sorrowful call for vigor and heroism. He also appreciates a refined elegance in both behavior and language. Various senators from earlier times earn his praise for their "elegantia vitae" (elegance of life).

Tacitus was primarily focused on people and their actions, rather than form or theories. He admired individuals who upheld dignitas and libertas, which were the traditional values of the ruling class. However, the times were not conducive to maintaining these values, and when it became impossible to uphold them, people resorted to taking their own lives.

This left Tacitus feeling disheartened and weary of such a tragic waste.

Illustration: Midjourney

Tacitus’ Latest Works

Tacitus had planned to write the histories of the reigns of Nerva and Trajan, as well as Augustus. However, there is no evidence that he ever completed these works. Had he managed to undertake these extensive tasks, which he referred to as curae (duties), he would have chronicled the entire span of the Roman Empire from its inception to the death of Trajan. In reality, Tacitus only completed the historical narrative from Tiberius' accession in 14 AD to Domitian's death in 96 AD.

In his later works, Tacitus developed a distinctive style. While it was influenced by Thucydides and more directly by Sallust, it achieved a level of epigrammatic sharpness that neither predecessor reached. Unlike the rich and full style of Livy, Tacitus' style was marked by concise incisiveness, elevating Sallust's approach to an even higher level.

Tacitus is less personal compared to many other historians. When assessing the fairness of his works, it's important to note that one of his historical pieces, Germania, is almost entirely impersonal, similar to the style found in the introductory passages of Thucydides.

Tacitus‘ Impartiality

It is said that Tacitus is not impartial, although he claims he is. In the opening chapter of Agricola he says:

"It is my purpose to write briefly the closing events of Augustus' reign, next the reigns of Tiberius and the others without indignation or favor, for I have no cause for either."

And again at the beginning of the Histories,

"But those who profess fidelity to truth must speak of each individual without affection and without hatred" (neque amore et sine odio).

The reason to study Tacitus is that, when reading his works, we gain slightly less information about Roman history than we might desire, but far more insight into his attitudes, perspectives, and philosophy than we might expect.

The opening sentences of his books reveal his concerns about morality, the expansion of the empire, comparisons between the past and present, and the conflict between tyranny and liberty.

As the French Renaissance philosopher Michel de Montaigne stated, “If his writings tell us anything about his qualities, Tacitus was a great man, upright and courageous, not of a superstitious but of a philosophical and high-minded virtue.”

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: