The Chains of the Empire: Slavery in Roman Society

Slavery in the Roman Empire was a complex institution deeply embedded in the social, economic, and political systems of the ancient world.

The Roman Empire built one of the most extensive and integrated systems of slavery in world history, economically and culturally. This system relied on a steady supply of enslaved individuals from various sources, including those born into slavery, captured in wars, sold by foreign and domestic traders, reclaimed as abandoned infants, and, in late antiquity, individuals who sold themselves or their children into slavery due to debt.

Enslavement was imposed on people from across the empire, without regard to race or ethnicity. Enslaved individuals contributed to sectors like agriculture, industry, domestic service, and even intellectual work, serving as the backbone of elite wealth production.

While resistance to slavery existed in forms like rebellion and escape, Roman society was also notable for its frequent practice of manumission, where slaves were granted freedom. This reflects a blend of ancient traditions of integrating captives and more modern practices of exclusion associated with slavery.

An Empire Built on Slaves

Roman slavery was deeply rooted in a Mediterranean culture where the practices of taking captives and holding slaves were almost universal. These traditions spanned across peoples, including the Semitic and Greek populations of the East, the Germanic and Celtic peoples of the North and West, and the Phoenicians, Africans, and Egyptians in the South.

Such practices were well established both before and during the peak of the Roman Empire (3rd century BCE to the 5th century CE), and continued after its fall. Recognizing this widespread acceptance of slavery, the Romans codified it in their legal framework. Roman jurists (a lawyer or a judge), relied on a dual system that made reference to the ius gentium (the law of all peoples) and the ius civile (civil law) to explain how individuals could become enslaved.

The ius gentium covered two primary pathways into slavery: being born into it or being taken captive in warfare. Romans followed the principle of partus ventrem sequitur (offspring follows the womb), which meant that the status of a child followed that of their mother. If the mother was enslaved, the child would also be born a slave, irrespective of the father’s status.

While there are no comprehensive statistics on the different avenues into slavery, modern historians agree that birth played the largest role in maintaining the Roman slave population. Still, captive-taking was also essential in bolstering the supply of slaves.

Significant events in which large numbers of people were taken captive are frequently recorded in ancient sources. Some conquests were so prolific that they temporarily caused a glut in the slave market, driving down prices. The Roman military, renowned for its efficiency, fed this market with countless captives.

The Astonishing Numbers of Slavery

For example, Julius Caesar, in his campaigns in Gaul between 58 and 50 BCE, is said to have captured and enslaved a million Gauls. In 57 BCE alone, he sold 53,000 Atuatuci tribespeople. When Caesar won the Battle of Alesia in 52 BCE, he distributed a Gallic captive to each of his 80,000 soldiers as spoils. These large-scale campaigns ensured a steady influx of captives into the Roman economy.

As Roman armies swept across the Mediterranean, they generated captives for the empire’s slave markets. Conquests brought in waves of new enslaved populations. When Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus defeated the Sardinians in 177 BCE, he sent 80,000 captives into the Roman slave market. Aemilius Paulus’s campaign in Epirus netted 150,000 captives.

The transition from the Roman Republic to the autocratic Empire under Augustus did not slow these trends. For example, when Titus sacked Jerusalem in 70 CE, 97,000 Jews were taken as slaves, and during Trajan’s campaigns against the Dacians in the early 2nd century CE, at least 100,000 Dacians were likely enslaved.

Roman society did not restrict enslaved individuals to manual labor alone. Many captives who possessed skills or knowledge were employed in specialized professions, such as medicine, architecture, and music. Notable figures like Publilius Syrus (a satirist), Manilius (an astronomer), and Staberius Eros (a grammarian) all came to Rome as enslaved people, illustrating the value Romans placed on skilled labor.

Young captives, if recognized for their talents, could be trained in specific professions rather than being sent to agricultural work. Inscriptions mention two boys from Parthia who were trained as a treasurer and a pedagogue to the imperial family, respectively.

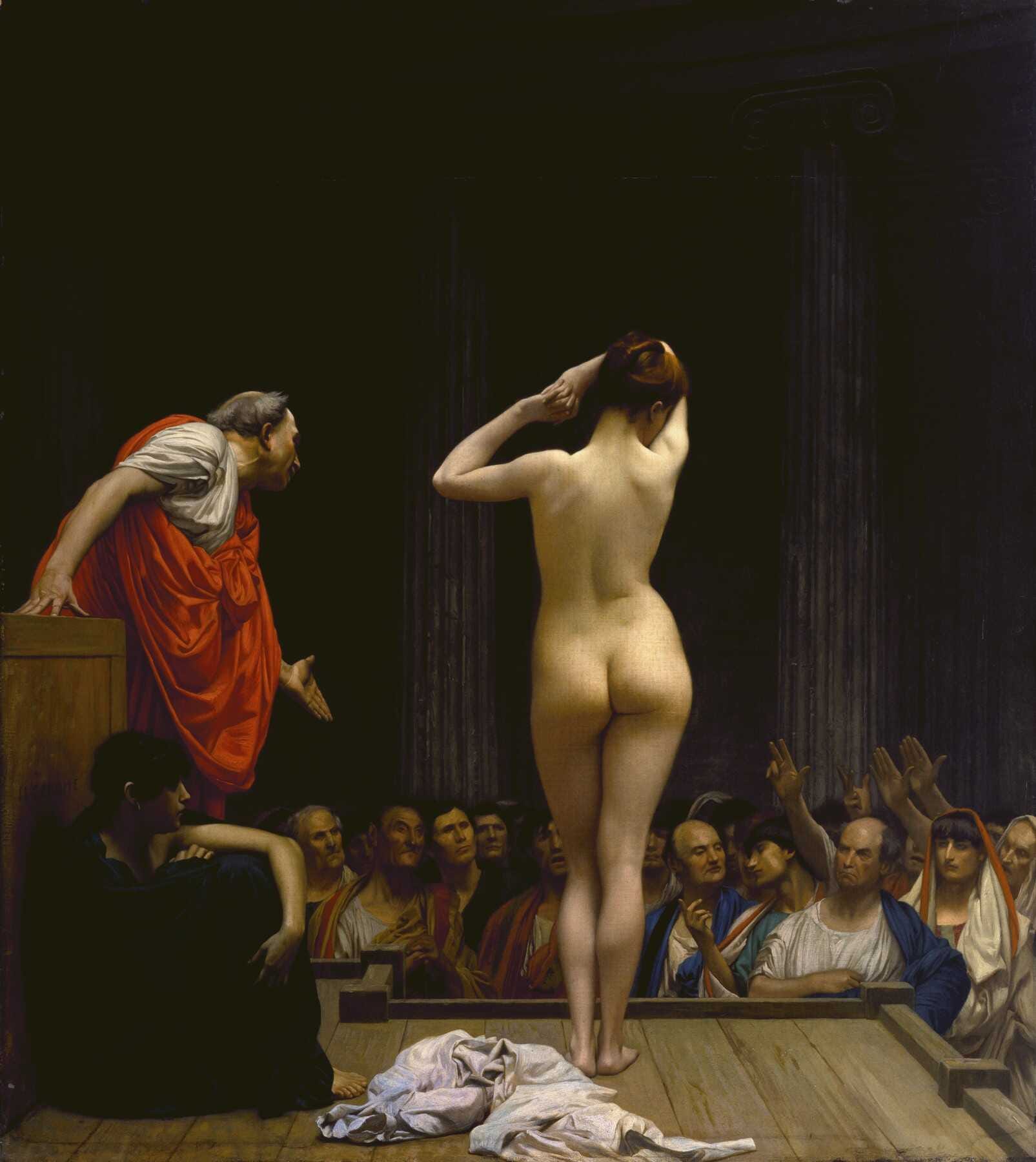

In Rome, the supply of slaves was vast, and the slave trade extended across the empire. Major markets existed in places like the Saepta Julia and near the Temple of Castor in Rome itself. The island of Delos, granted free-port status by Rome, became a significant hub for slave trafficking, reportedly dealing with as many as 10,000 humans per day.

The sources of slaves spanned the entire empire, and documents like contracts of sale preserved on papyri confirm the wide range of ethnicities involved. While Roman citizens were generally protected from enslavement, exposure of unwanted infants was common. Enslavers would often claim these abandoned children, raise them, and then sell them as slaves. Wet-nurse contracts, which ensured the care of such children, illustrate this practice.

As Rome’s empire expanded, certain regions transitioned from being sources of slaves to becoming integral parts of the empire. For example, following Caesar's conquest of Gaul, the Gauls gradually became Roman subjects, and by the mid-1st century CE, Gallic aristocrats were serving in the Roman Senate.

However, Rome’s military and technological limitations meant the empire remained surrounded by “barbarians” who were considered potential sources of slaves. These populations—such as the Scotti (Irish), Picti (Scots), Frisians, Alamanni, Sarmatians, and others—supplied the Roman slave market through human trafficking.

Before 212 CE, when the Emperor Caracalla extended Roman citizenship to most of the empire’s inhabitants, only a minority of the population were citizens. Non-citizens followed their own regional legal systems, many of which permitted practices like child sale and debt bondage.

Even citizens were not entirely immune to becoming slaves.

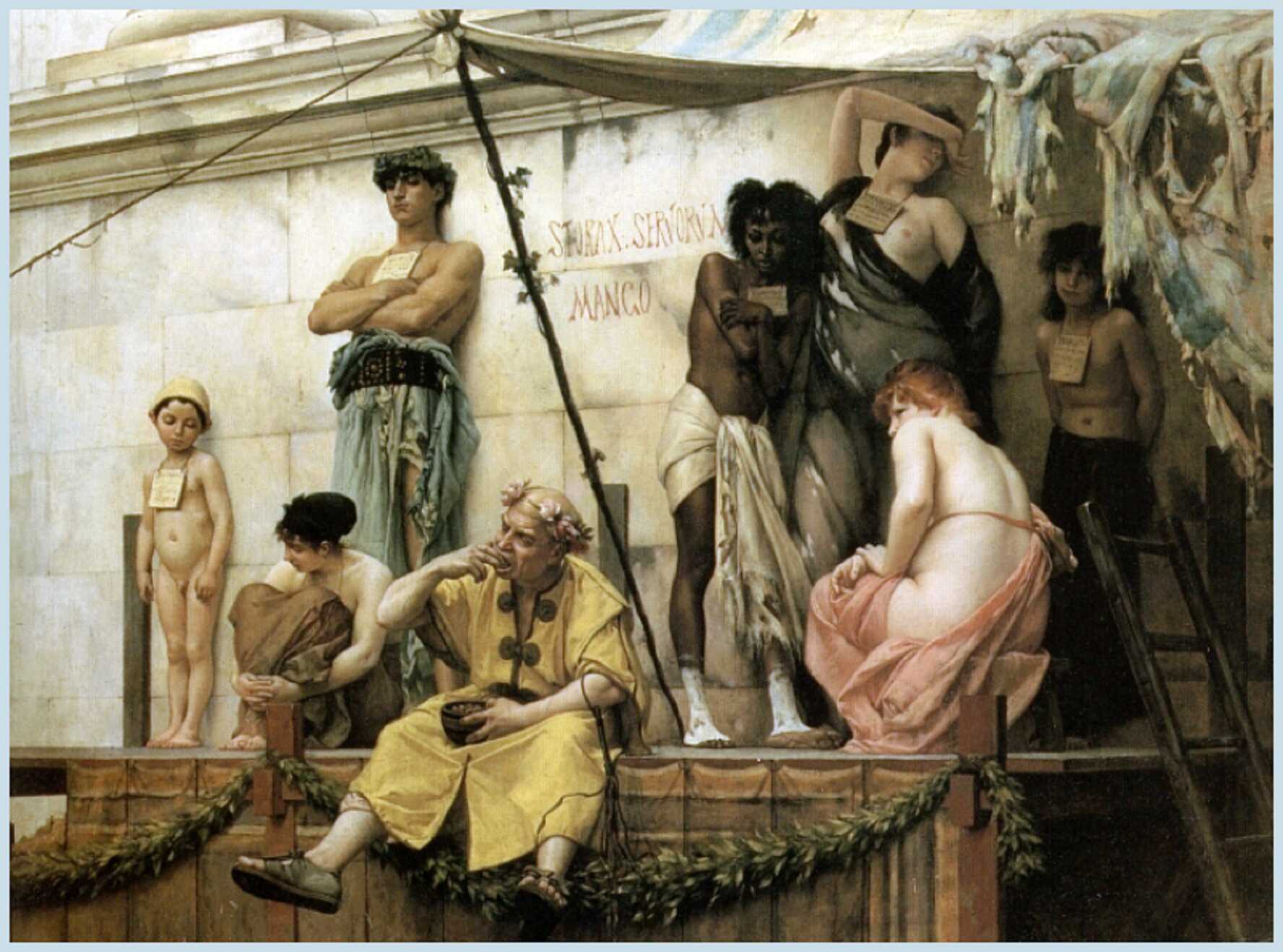

A Roman Slave Market, by Jean-Léon Gérôme. Public domain

In earlier periods, Romans allowed citizens to fall into debt slavery, a practice that reemerged in the 4th century CE. Over time, as Christianity spread through the empire following Constantine's conversion, attitudes toward slavery shifted. Constantine outlawed the exposure of infants, though he allowed parents to sell their children into long-term indentured servitude.

Throughout its history, Rome’s slave supply was maintained through multiple streams—war, birth, trade, and abandonment—which adapted to changing social, territorial, legal, and religious landscapes. Even with these shifts, the demand for slaves was always met, evidenced by the stability of slave prices throughout the imperial era, typically costing about five years’ wages for a day laborer. (Slavery in the Roman Empire, by Noel Lenski)

The Largest Slave Society in History

Building upon the institutions of the Greek and Hellenistic worlds, ancient Rome developed the largest slave-based society in history. There are several reasons for characterizing the Roman Empire, especially its Italian core but also its provinces, as a slave society.

Slaves, numbering in the millions and spread throughout the empire, made up a significant portion of the total population. In certain key areas, slaves were more than just present; they supported a “slave mode of production,” which involved a tightly integrated system of enslavement, slave trade, and labor, where slaves were systematically controlled by their masters for both production and reproduction.

Crucially, Rome qualifies as a slave society due to the structural reliance on slavery: elite groups, particularly in the empire’s core regions, depended heavily on slave labor to generate wealth and maintain their dominant status.

Since slavery was central to Rome's primary production processes, it was not only a ‘slave economy,’ but also a ‘slave society,’ where slave ownership was a defining social relationship. These terms can be used interchangeably, particularly in segments of society where slaves and former slaves continuously surrounded slave owners, influencing their interactions with free citizens. In essence, Rome's entire social and economic structure would have been fundamentally different without slavery.

In many respects, slavery in classical Athens and Roman Italy was similar. Both systems were primarily dependent on external sources of slaves (outsiders) and treated slaves as property or chattel. Slaves were captured or bought, brought to densely populated areas, and employed across a variety of occupations in both rural estates and urban settings.

The key determinant in these economies was access to land rather than labor. Despite variations in scale and minor differences in practice, the only major distinctions between Greek and Roman slavery were in the frequency of manumission and how freedpersons were integrated into society. While conditions may have differed slightly in other regions, focusing on the best-documented areas shows that Roman slavery, with some modifications, mirrored Greek slavery.

This similarity is not surprising, as the Roman imperial economy was essentially a continuation and expansion of the Hellenistic economy, just as Roman chattel slavery can be seen as an extension of Aegean slavery systems, potentially influenced by the practices of Western Greeks and Carthaginians. (Slavery in the Roman economy, by Walter Scheidel)

A Slave by Decision

Rome was familiar with a different type of slavery known as "contractual slavery," in which individuals voluntarily chose to become slaves. While some Romans opted for slavery as a means of survival, others saw it as a pathway for social or economic advancement.

The decision to enter into slavery wasn't typically made out of ignorance, impulsiveness, or irrationality; instead, it indicated a potential improvement in the individual’s economic status or welfare. This type of self-sale brought Roman society closer to what welfare economists describe as a Pareto-efficient or optimal allocation, where no mutually beneficial trade is left undone, and any changes would make at least one party worse off.

Contrary to historians' typical view of slavery as an arrangement benefiting only one side, contractual slavery in Rome was advantageous for both parties. Slave owners had incentives to purchase individuals, while those selling themselves sought to improve their economic conditions.

The benefits individuals gained from selling themselves into slavery depended on the structure of the slave market. They profited more when buyers acted competitively (as price takers) rather than monopolistically (as price setters). This competitive behavior, particularly in affluent regions, weakened local monopsonistic power, especially in agricultural areas.

Despite ample evidence supporting the existence of contractual slavery in Rome, this concept has often been overlooked or minimized by scholars, partly due to the discomfort with acknowledging aspects of slavery that might appear sympathetic. Scholars have trivialized the notion of contractual slavery by conflating market choices, even among undesirable options, with forced slavery, ignoring its distinct economic dynamics.

Clear evidence of the legal basis for self-sale into slavery in Rome comes from the jurist Marcian, who, writing in the second quarter of the third century CE, explains that individuals over the age of twenty could voluntarily sell themselves into slavery under ius civile (Roman civil law) in exchange for a share of the sale price.

This self-sale process placed these individuals on the same legal footing as those who became slaves through ius gentium (the law of nations), which applied to those captured in war or born to enslaved mothers. Roman law made no distinction between the final status of self-sellers and those captured by force—both were regarded equally as slaves.

Earlier in the third century, Ulpian (a roman jurist) also mentioned self-sale into slavery, referring to it as ad actum gerendum (to secure the position of a steward or actor) or ad pretium participandum (to perform an act or share in the sale price), providing further confirmation of the practice. These references show that self-sale was not an unusual or exceptional legal phenomenon in Roman society, but part of the broader legal framework governing slavery.

Not long after Ulpian the jurist Macer observes: “Certain offenses, which bring no penalty, or a relatively light one, on a civilian, [are visited] more heavily on a soldier". For Menander [first quarter of third century CE] writes that if a soldier takes part in stage plays or permits himself to be sold into slavery, he should suffer capital punishment.

For a soldier, selling oneself into slavery would be considered equivalent to desertion, which is a serious offense. However, for civilians, self-sale was not a criminal act, but rather, like performing on stage, something that was socially disapproved of yet still legal. Ulpian, in a discussion about fugitive slaves, mentions “a slave who seeks asylum or goes to a place frequented by those who declare (postulo) themselves for sale.”

The term "asylum" here likely refers to an imperial decree or possibly sacred spaces such as temple precincts, similar to those in Greece. While some might suggest that the "place" could be the office of the praefectus urbi (the urban prefect), who had the authority to sell mistreated slaves, this interpretation is unlikely.

First, the office of a high-ranking public official wouldn’t simply be referred to as “place,” which indicates multiple locations. Second, the reference to "those" seeking to sell themselves implies a group distinct from slaves who were dissatisfied with their current masters.

Morris Silver, in his work "Contractual Slavery in the Roman Economy," interprets Ulpian’s passage to mean that fugitive slaves may have sought refuge in a venue specifically designated for free people (homines liberi) who wished to sell themselves. The existence of such specialized self-sale venues would only be viable when the slave market reached a certain scale.

As for whether the legal possibility of self-sale by free individuals was a new development of the late second or early third century, this seems unlikely. Evidence suggests similar practices were already noted earlier, with references to such acts appearing in the writings of Scaevola in the first century BCE and possibly under Hadrian in the first century CE. Additionally, Gaius’ Institutes also envision the self-sale of Roman citizens (cives Romani) through mancipatio (formal transfer of ownership):

“Now mancipation… is a sort of imaginary sale (imaginaria venditio), and it too is an institution peculiar to Roman citizens.

It is performed as follows: in the presence of not less than 5 Roman citizens of full age and also of a sixth person, having the same qualifications, known as the libripens (scale-holder), to hold a bronze scale, the party who is taking by the mancipation, holding a bronze ingot [while holding the object], says: “I declare that this slave is mine by Quiritary right (the right of citizens), and he be purchased by me with this bronze ingot and bronze scale.”

He then strikes the scale with the ingot and gives it as the symbolic price to him from whom he is receiving by the mancipation.

It is thus set forth that both servile and free persons are mancipated, as also such animals as are mancip (mancipable), namely oxen, horses, mules, and asses; lands also, whether built or unbuilt on, are mancipated in the same way, if they are mancipi, as are Italic lands.

The mancipation of lands, differs from that of other things in this point only that persons, servile and free, and animals that are mancipi cannot be mancipated unless they are present—indeed, the taker by the mancipation must grasp the thing which is being mancipated to him, which is why the ceremony is called mancipatio, the thing being taken by the hand— whereas lands are regularly manumitted at a distance.”

It is unclear whether the ritual described by Gaius is genuinely ancient or a later recreation of an older practice. However, Gaius’ description suggests that self-sale through mancipatio was a well-established practice in his time, around the mid-second century CE. Additionally, Gaius implies that this practice may have originated in "ancient times."

By the time of Justinian, mancipatio had been abolished, but during Gaius’ era, the self-sale transaction was made official through the transfer of payment to the individual voluntarily, selling themselves into slavery.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: