The Ancient Blueprint Behind Every Modern Stadium

What survives now is only the emptiness of a vast space, yet it carries the weight of a city’s anticipation and the memory of its most restless hours.

Every modern stadium, from the roar of football fans to the echo of concerts under open skies, owes something to a forgotten masterpiece of the ancient world. It wasn’t just a venue — it was an idea so advanced that its echoes still shape the way we gather today. Built for speed, spectacle, and the spirit of competition, this place became the heart of an empire long before it inspired ours.

The Rise, Fall, and Rediscovery of the great stadium

The Circus Maximus was the first and largest structure ever built for the Roman ludi — the public games that blended religion, politics, and spectacle. Its size and design made it a model for circuses across the Roman world.

Modern understanding of the site owes much to more than a century of research. Early investigations began with Bigot in 1908 and were continued through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries by numerous scholars and institutions. Excavations, core drillings, and more recent geophysical surveys have revealed the gradual transformation of the area over two millennia.

The first permanent masonry structures were built under Julius Caesar. After enduring fires, reconstructions, and imperial enhancements, the Circus reached its grandest form under Emperors Domitian and Trajan. It remained active until 549 CE, when the Ostrogothic king Totila hosted the final games. After the sixth century, neglect and looting reduced the site to a quarry for building materials. Over time, floods and sediment buried the original track beneath ten meters of earth.

The valley of the Circus Maximus changed character repeatedly through the centuries: farmland during the Middle Ages, a Jewish cemetery in the seventeenth century, and an industrial zone by the nineteenth and early twentieth. Gasometers, workshops, and warehouses stood where chariots once raced.

In the Fascist era, the space was cleared and reused for trade fairs and national exhibitions, including the 1934 Textile Show and the 1939 Exhibition of Italian Autarkic Minerals. It was reshaped into a park preserving the form of the ancient arena. By the mid-twentieth century, the site was formally designated as the Circus Maximus Monumental Area.

Archaeologists then removed the industrial remains, uncovering the lower seating tiers, outer porticoes, and sections of the curved hemicycle. These can still be seen today beside the medieval Torre della Moletta, a square tower with battlements erected by the Frangipane family.

Further excavations in 1998, using large-diameter shafts, examined the remains of the central barrier — the spina. For the first time, researchers could visually study the structural core of the euripus (the central water channel) and confirm that Roman layers survive eight to eleven meters below ground. Two main anthropic layers were identified: a modern one, up to four meters thick, and deeper strata containing the ancient remains themselves. (“Cultural Heritage Sites Conservation and Management: The Case of the Circus Maximus in Rome” by Valerio Ruscito)

The Scale of the Circus Maximus

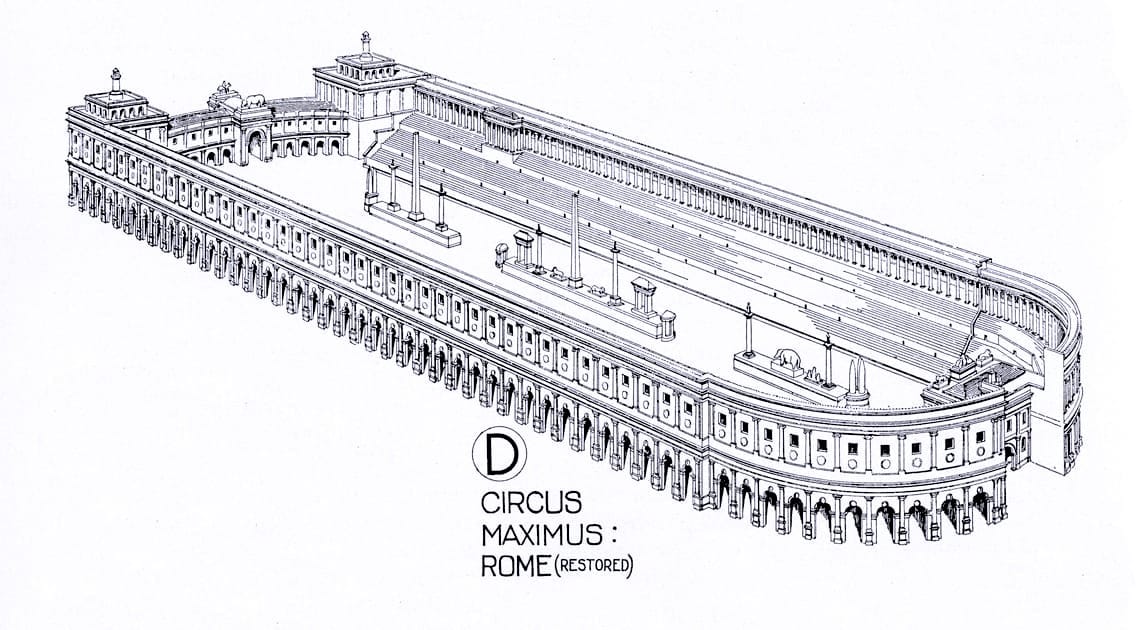

The Circus Maximus stands among the oldest and most remarkable monuments in Rome — an arena that dwarfed every other structure of its kind. Built for the thrilling spectacle of chariot racing, it stretched roughly 600 meters in length and 140 meters in width, capable of seating more than 250,000 spectators during the height of the Roman Empire (circa 100 BCE–300 CE). Its sheer scale made it the beating heart of Roman entertainment, and a model for racetracks across the ancient world.

A Valley Turned to Stone: Building in the Murcia Basin

The stadium rose in the wide, marshy Murcia Valley, nestled between the Palatine and Aventine Hills. This valley once carried one of the major tributaries of the Tiber River, flowing down from the volcanic Alban Hills. At first glance, it was an unlikely location for such a colossal construction — a flood-prone plain of soft, unstable alluvium.

Yet this very quality may have determined the choice. The valley’s waterlogged soil, unsuitable for housing or temples, offered open space ideal for the long, sweeping track that the ludi circenses required.

The Romans faced the challenge of transforming a geologically young landscape marked by steep slopes, seasonal torrents, and unstable ground into a foundation capable of supporting one of the largest stadiums ever built. Understanding how they achieved this feat has long fascinated engineers and archaeologists alike. Through careful drainage, leveling, and the use of robust retaining structures, they stabilized the valley floor and created an enduring base that would support centuries of races, festivals, and triumphs.

Recent geophysical studies have allowed researchers to piece together the environmental history of the Murcia Valley. Beneath the modern surface lies evidence of the original floodplain that once made the site inhospitable. Surveys and excavations reveal how the Romans drained, filled, and reinforced the ground to form a stable arena platform — a marvel of ancient engineering that kept the Circus standing until well into the Middle Ages. (“Geology of the Murcia Valley and Flood Plain Modifications in the Construction of the Circus Maximus, Rome, Italy” by Elena Carpentieri, Donatella de Rita, and Giuseppe Della Monica)

The Circus and the Birth of Rome’s Spectacle

For over a millennium, horse racing formed one of Rome’s defining entertainments, and its most iconic arena — the Circus Maximus — was steeped not only in sport but in myth. Tradition holds that this vast space was also the setting of the rape of the Sabine women, a foundational tale in Roman lore. Livy, writing at the turn of the first century BCE, explains that Romulus deliberately chose the Circus as the stage for this fateful event:

“The Roman state had become strong enough to hold its own in war with all the peoples along its borders, but a shortage of women meant that its greatness was fated to last for a single generation … Romulus, to gain time till he found the right occasion, hid his concern and prepared to celebrate the Consualia, the solemn games in honour of equestrian Neptune. He then ordered that the spectacle be announced to the neighbouring peoples. He gave the event great publicity by the most lavish means possible in those days. Many people came … from Caenina, Crustuminum and Antemnae; the entire Sabine population came, wives and children included … they marvelled that Rome had grown so fast. When it was time for the show, and everybody was concentrating on this, a prearranged signal was given and all the Roman youths began to grab the women. Many just snatched the nearest woman to hand, but the most beautiful had already been reserved for the senators and these were escorted to the senators’ houses by plebeians who had been given this assignment.”

— Livy, History of Rome

From its mythical foundation under the Etruscan kings of the sixth century BCE (Livy), through its monumental reconstructions under the emperors, and down to its modern incarnation as a public park, the Circus Maximus has embodied the evolving relationship between power, space, and spectacle. This progression — from regal ritual ground to republican festival arena to imperial monument — reveals how the aristocracy continually reshaped the Circus to project authority, celebrate divinity, or win popular favor.

The architectural and functional transformations of the Circus, spanning more than two millennia, illustrate not only the adaptability of public venues but also their power as instruments of social negotiation. Ancient sources attest that the Circus was both a space of unity and distraction. It could dissolve class distinctions as people from every stratum gathered to watch the ludi (Suetonius, Claudius; Tacitus, Annals), yet it also induced a collective frenzy — an intoxication of sight and sound that erased awareness and restraint. As Ovid observed, it was uniquely permissive:

“The Circus was the only place where men and women sat together.”

— Ovid, Ars Amatoria

In the legendary abduction of the Sabine women, this loss of awareness — the surrender to spectacle — becomes the very instrument of destiny. The Circus Maximus, born in myth as the scene of deception and desire, would remain the enduring theater of Rome’s passions: a place where glory, pleasure, and power forever raced side by side.

The Etruscan Origins: When Kings and Gods Shaped the First Circus

The beginnings of the Circus Maximus reach back to the twilight of Rome’s monarchy, before the Republic and long before imperial grandeur transformed the valley. Tradition credits its foundation to Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, Rome’s fifth king (616–579 BCE), during the era of Etruscan dominance over the city — vae victis, “woe to the conquered,” as Livy remarks (History of Rome).

Though Livy attributes the commission to Tarquinius Priscus, modern historians suspect this to be more legend than fact, molded by Livy’s political motives and his tendency to shape early Roman history into a moral narrative rather than a verifiable account.

Whether begun by Tarquinius Priscus or completed by his grandson Tarquinius Superbus, it is clear that the Circus was an early royal project. The kings allowed Rome’s aristocracy to construct raised viewing platforms — the pulvinar (cushioned couch) — where they could enjoy an elevated view of the horse races and boxing contests said to have been imported from Etruria. While the elder Tarquin’s existence may be debated, the younger Tarquin was almost certainly real, and scholars generally agree that the Circus was completed before the fall of the monarchy, around 509–500 BCE.

Archaeological findings corroborate this early date. A stone seat inscription discovered near the shrine of Murcia, dated to 494 BCE, records a magistrate named Manius Valerius Maximus who occupied a private seat. Such inscriptions, considered among the most reliable evidence for early Roman chronology, confirm that the Circus was already functioning in the early Republic.

The Murcia Valley, where the Circus stood, lay between the Aventine and Palatine Hills, stretching roughly 621 meters in length and 118 meters in width. In early times, it was fertile farmland nourished by floods from the Tiber River and a now-lost tributary stream that divided the valley. This stream — later re-excavated by Pope Calixtus II and renamed the Acqua Mariana — once powered mills at the eastern end near the Torre della Moletta and irrigated crops in the surrounding fields.

The earliest Circus must have been a simple pastoral track, “with nothing more than turning posts, banks where spectators could sit, and some shrines and sacred spots” as John Humphrey, the American archaeologist and classical scholar, says. Wooden stands and seating, vulnerable to rot from flooding and damp soil, required constant repair — offering the elite opportunities to display generosity through munera, gifts to the people.

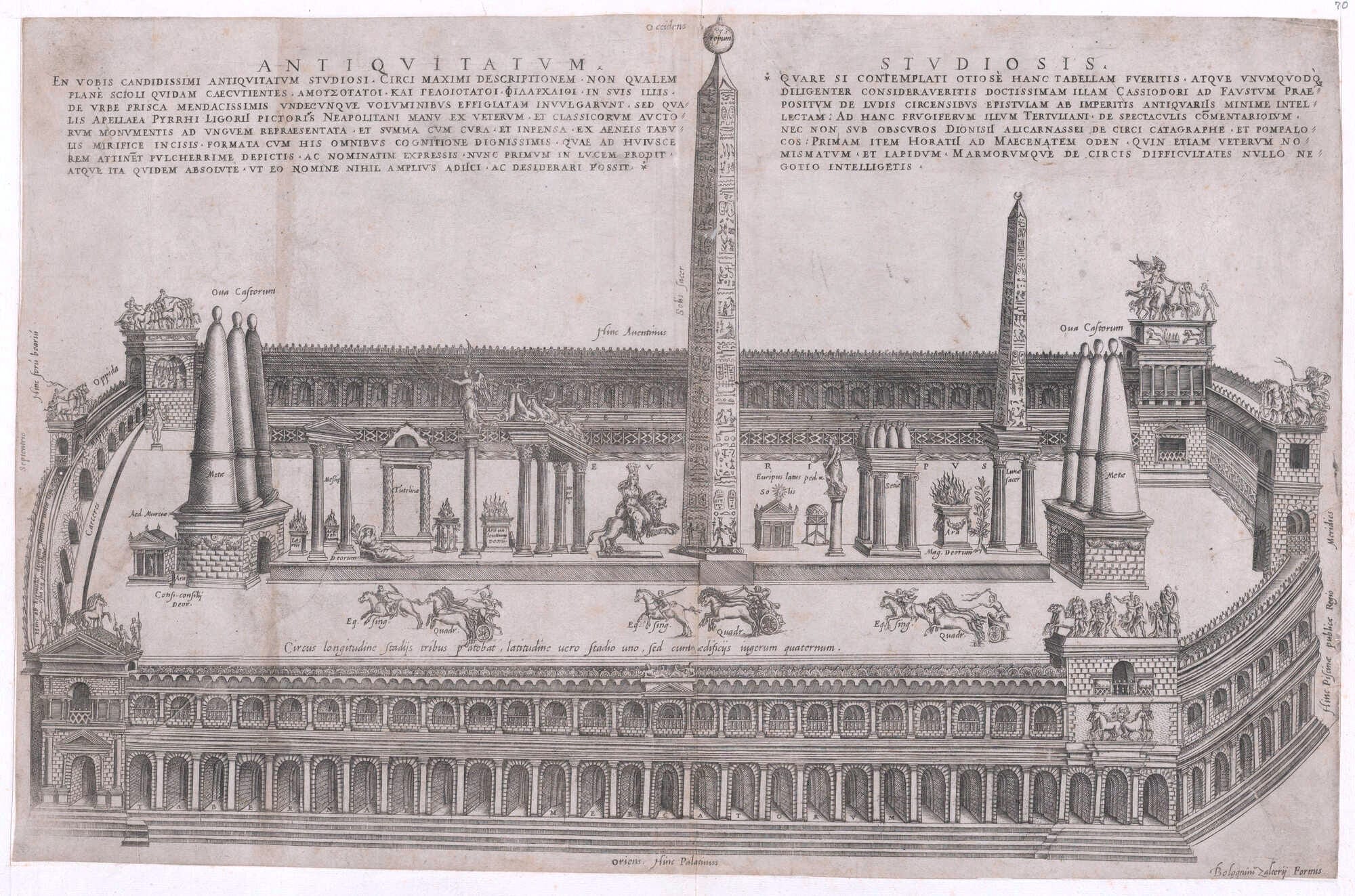

The first turning posts (metae), located near the banks of the old stream and perhaps linked to the goddess Murcia, consisted of three conical stone pillars on each end of the track. Between them ran an open drainage canal, which likely served as the earliest form of the spina, the central barrier that would later become the Circus’s defining feature.

As Ovid recalls in his Metamorphoses, these early markers shaped the very rhythm of Roman sport — where kings, gods, and earth itself laid the foundation for the city’s most enduring spectacle.

Where Gods, Games, and Emperors Collided: The Sacred Power Behind the Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus was far more than a racetrack — it was the beating heart of Roman religion, politics, and public life. From its earliest days, the arena fused cultic ritual and spectacle, embodying a uniquely Roman blend of piety (pietas) and propaganda. Even as political systems shifted from monarchy to republic and empire, the Circus remained a stage where sacred rites, civic devotion, and elite ambition intertwined.

The valley’s early shrines reveal how the Romans blurred the line between worship and entertainment. The southeastern turn of the track passed between two ancient sanctuaries: one dedicated to Murcia, a mysterious goddess associated with Venus, fertility, and the valley’s stream, and another to Consus, the hidden god of grain and underground stores.

At the Consualia, horses and mules were crowned with flowers and released from labor to race — an agricultural thanksgiving turned public spectacle. This merging of sacred ceremony and civic showmanship laid the foundation for Rome’s culture of munera, political gifts to the people disguised as religious offerings (Juvenal, Satires). As Seneca warned,

“There is nothing so damaging to good morals as to hang around at some spectacle. There, through pleasure, vices sneak in more easily.” Letters

Archaeology confirms that horse racing was already practiced here in the sixth century BCE, and the earliest dimensions of the track may have been determined by the distance between the shrines of Murcia, Consus, and the Ara Maxima of Hercules, a pre-Roman altar that anchored the valley’s sacred geometry. In later centuries, the altar of Consus became a fixed feature beneath the southeastern meta, while Murcia’s shrine was rebuilt near the euripus, the channel dividing the track.

As the Circus evolved, so did its theology. By the Imperial period, the site reflected a solar and lunar cosmology: Apollo (Sol) and Luna, with their temples crowning the Palatine and Aventine Hills, represented the chariots of the sun and moon racing across the heavens. The Circus itself became a cosmic arena, its track symbolizing the circuit of time — day and night, life and eternity.

The emperor, identified with Sol, presided as both ruler and divine charioteer. Augustus’ placement of an Egyptian obelisk at the Circus’s center fused Roman statecraft with solar worship, turning architecture into imperial theology.

By the first century CE, the Circus Maximus could seat up to 150,000 spectators (some claimed 250,000), an amphitheater of faith and frenzy. Fires, floods, and rebuildings under Tiberius, Claudius, and Trajan transformed it from wood to stone, culminating in the grand structure that became the largest stadium of the ancient world. Trajan’s all-stone reconstruction secured its final form — a monument where divine order and imperial ambition met in a single, thunderous spectacle.

In the end, the Circus Maximus stood as Rome’s cosmic theater — where gods raced across the heavens, emperors claimed their divinity, and the people of the Eternal City learned to worship through the thrill of the games. (“Rome’s Seat of Passion: An Assessment of the Archaeology and History of the Circus Maximus” by Cody Scott Ames)

Inside the Spectacle That Ruled the City

Tradition cast Tarquinius Priscus as founder (Livy). Livy later notes the first permanent starting gates in 329 BCE and their rebuilding in 174 BCE, when seven wooden eggs were set on the spina to count laps; the turning posts he mentions must have been restorations, not novelties.

Julius Caesar lengthened the track and ran an encircling euripus (Suetonius). In 33 BCE, Agrippa added seven bronze dolphins and a second set of eggs by the carceres for lap-marking (Dio). After the 31 BCE fire (Livy), Augustus built the pulvinar beneath the Palatine — an imperial shrine-box for viewing, where divine images were seated after the pompa, and in 10 BCE he set an obelisk on the spina to honor the Sun and memorialize Egypt.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus wrote:

Tarquin [fifth king of Rome] also built the largest of the Circuses, which lies between the Aventine and Palatine hills ... in the course of time this work was to become one of the most beautiful and remarkable buildings in Rome; the Circus being 3.5 stadia long [2100 feet] and four plethra wide [400 feet]. There is a canal around it on the two long sides and on one of the shorter ones: this is ten feet wide and ten feet deep. Behind this are three tiers . . . seating 150,000 persons. On the outside of the Circus there is another portico of one storey, which has shops with apartments over them. These have entries and stairways for the spectators at each shop, so that thousands of people may enter or leave without congestion. Roman Antiquities

Those wooden arcades — home to cooks, astrologers, and prostitutes — kindled the AD 64 blaze (Tacitus). Pliny the Elder ranked the Circus among the world’s great works and gave a higher capacity, 250,000, likely counting hillside sightlines (Pliny, Natural History).

After another great fire (perhaps AD 80), Trajan completed the all-stone rebuild by AD 103 —

“rivaling the beauty of temples,”

says Pliny the Younger — with three tiers, arched orders below, marble in the lowest seating, and zoned terraces. Unlike the theater and amphitheater, seating here was less segregated: senators had the podium front (Suetonius), equites sat behind (Tacitus), and men and women sat together — a fact Ovid mined for flirtation.

Though born for ludi circenses, the Circus staged gladiatorial shows, venationes, athletics, and processions. By Augustus’ time, seventy-seven festival days filled the year, with races on seventeen; ten to twelve races a day were standard until Caligula doubled them and twenty-four became typical (Dio). Extremes occurred — Domitian ran one hundred short-lap races in a day (Suetonius); Commodus crammed thirty into two hours (Dio) — but logistics (horses stabled on the Campus Martius) kept such marathons rare.

Starts came from twelve carceres (six per side) near the Forum Boarium entrance; the presiding magistrate signaled the release. The far sphendone held the processional gate, rebuilt in AD 80 as a triumphal arch for Titus’ Judaean victory. Shrines on the spina honored Consus and Murcia; at each end stood the metae — triples of gilded cones atop semicircular plinths. A race ran seven laps (spatia) — thirteen turns counter-clockwise — just over three miles, often eight to nine minutes, the cinematic pace of Ben-Hur.

For fairness, the carceres were set on a curve so each team hit the break line at equal distance; drivers kept lanes until that line, then fought for position. Lots assigned gates; the magistrate dropped the white mappa, gates flew, and the surge began.

The classic quadriga matched two central yoke horses with two trace horses; the right yoke-mate was prime, and the inside funalis had to be stout to take the turns. It suffered most from concussions, strains, or fractures between spina/metae and the yoke. Pelagonius lists hazards: whip-strikes to the eyes, tongues cut by harsh bits, and wheel or axle blows.

Tails tangled in reins — often bound or even cut. Breeding was meticulous; racing began near age five, with long careers. Studs in North Africa and Hispania shipped horses on hippagoi (horse transports).

Aurigae were mostly slaves or freedmen, legally infames like gladiators. They wrapped reins around the waist for leverage — deadly in crashes unless the curved knife in their harness freed them. Fouls were routine; emperors’ whims could weigh heavily — Martial hints that prudence sometimes counseled restraint. The crowd, though, could force restarts — Ovid speaks of toga-waving protests; the reruns became so many that Claudius capped them (Dio, LX.6.4–5).

Fame and fury mixed. Ammianus tells of witchcraft trials; one driver burned despite having

“given such general pleasure".

Curse tablets begged demons to

“torture and kill the horses of the Greens and Whites,”

to

“bind every limb … and knock out their eyes.”

Yet fortunes were made: purses of 15–60,000 sesterces per win; Juvenal gripes a driver earns a hundred times a lawyer; Martial brags Scorpus won

“fifteen bags of gold in an hour.”

Gaius Appuleius Diocles amassed 35,863,120 sesterces, with 1,462 wins in 4,257 starts over 24 years; Scorpus died at twenty-six with 2,048 victories.

Gaius Appuleius Diocles, Charioteer of the Red Stable, a Lusitanian Spaniard by birth, aged 42 years, 7 months, 23 days. He drove his first charuiot for the White Stable in [122 A.D.]; he won his first victory for the same Stable in [124 A.D.]. He drove for the first time for the Green Stable in [128 A.D.]. He won his first victory for the Red Stable in [131 A.D.].

Grand Totals:

He drove chariots for 24 years, started 4,,257 times, won 1,462 times, of which 110 were in the opening race.

In single-entry races he won 1,064 victories, winning 92 major purses

32 of them (including three with six-horse teams) at 30,000 sesterces.

28 of them (including two with six-horse teams) at 40,000 sesterces.

29 of them (including one with a seven-horse team) at 50,000 sesterces.

3 of them at 60,000 sesterces.

In two-entry races he won 347 victories, including four with three-horse teams, at 15,000 sesterces.

In three-entry races he won 51 victories.

He won or placed 2,900 times, taking 861 second-places, 576 third-places, and 1 fourth-place at 1000 sesterces.

He tied a Blue for first-place 10 times and a White 91 times, twice for 30,000 sesterces.

He won a total of 35,863, 120 sesterces.

In addition, in races with two-horse teams for 1000 sesterces, he won three times, and tied a White once and a Green twice. He took the lead and won 815 times, came from behind to win 67 times, and won under handicap 35 times, won in various styles 42 times, land won in a final dash 502 times—216 over the Greens, 205 over the Blues, 81 over the Whites.

He made nine horses 100-time winners, and one horse a 200-time winner. Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum XIV. 2884 (Rome, 146 A.D.)

The Circus was also Rome’s loudest political barometer — the people petitioned between heats; emperors were expected to attend and look delighted. Dio records crowds crying,

“How long are we to be waging war?” (AD 196).

Push too far — as Caligula did — and cheers turned to peril; he dragged dissenters from the stands.

Factions — Reds, Whites, Blues, Greens — grew from private stables into monopolies. By the fourth century, the emperor absorbed control; senior charioteers managed operations and horses came from imperial stables. Devotion bordered on madness: Ammianus laments a populace whose

“temple … dwelling … meeting-place … is the Circus Maximus,”

rushing there before dawn, living and dying by a turn at the post. Christian critics condemned the place as a school of vice: Tertullian calls its allure a “madness”; Cassiodorus sees Blues and Greens trading “frantic insults” as if the state itself were at stake (Variae).

Ironically, their polemics preserve details we’d otherwise lack — eggs for Castor and Pollux, dolphins for Neptune, and the mappa’s origin when Nero tossed his napkin to signal lunch’s end and the races’ start.

After AD 541, consuls vanished and funding waned; Procopius notes the last races in AD 550 (Gothic Wars). For a thousand years, Rome’s people forgot themselves here — laughing, pleading, cursing, praying — while horses and men traced the city’s fortune in sand and thunder.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: