Inside Roman Society: How Ordinary Life Shaped an Extraordinary Empire (Part 1)

Behind Rome’s power and conquests lay the daily lives of its people. From family and education to poverty, slavery, law, and spectacle, their routines and struggles reveal how ordinary Romans shaped the empire’s enduring legacy.

Beneath the marble monuments and imperial conquests that defined Rome’s grandeur lay a vibrant and complex social world. Families bound by tradition and law, merchants and bankers fueling the economy, soldiers marching across frontiers, and citizens gathering in baths or amphitheaters—all formed the daily fabric of an empire that stretched across continents.

To understand Rome not only as a state but as a lived experience, we must look beyond emperors and wars to the patterns of ordinary life: how Romans loved, worked, worshiped, and played.

The Legacy and Allure of Roman Social History

Roman social history is inseparable from the broader history of the empire itself. To study it is to study human beings in the past—how they lived, worked, worshiped, and interacted within one of history’s most influential civilizations.

Roman society fascinates not only because of its own richness but also because it sits at the crossroads of legacy and contrast: its ideas and institutions helped shape the modern world, yet its values and structures remain strikingly different from ours.

Rome’s expansion across the Mediterranean and into northwestern Europe made it the transmitter of Greek culture and the channel through which Graeco-Roman traditions were passed into medieval Europe and beyond. From Latin language and literature, which seeded later European literatures, to Roman law, which became the backbone of legal systems, to the institutions of the Western Church and enduring models in art and architecture—the Roman contribution is woven deeply into Western heritage.

At the same time, this inheritance must be seen within a broader web: Greek philosophy and culture, Jewish religious thought, and even the less-recorded contributions of Celts and other peoples, all left marks on Roman society.

Crucially, Roman identity was not based on ethnicity but on legal status. Citizenship, conferred with a generosity unusual in antiquity, created a diverse and complex society where outsiders could become insiders. This inclusivity, coupled with the empire’s vast reach, gave Rome a social fabric unlike any other in antiquity.

For modern readers, the Romans occupy a unique place: they are close enough in thought and expression to seem familiar, yet distant enough in customs and institutions to challenge us. Their world was pre-industrial, deeply reliant on slavery, and ordered by hierarchies alien to our values.

Still, the voices of Cicero, Caesar, or the anonymous Roman citizen ring with a clarity that can seem more accessible than those of medieval figures centuries closer to us in time. Roman social history thus allows us to recognize both the echoes of our own experience and the strangeness of a world long past—a dual perspective that makes it endlessly compelling.

The Framework of Roman Society

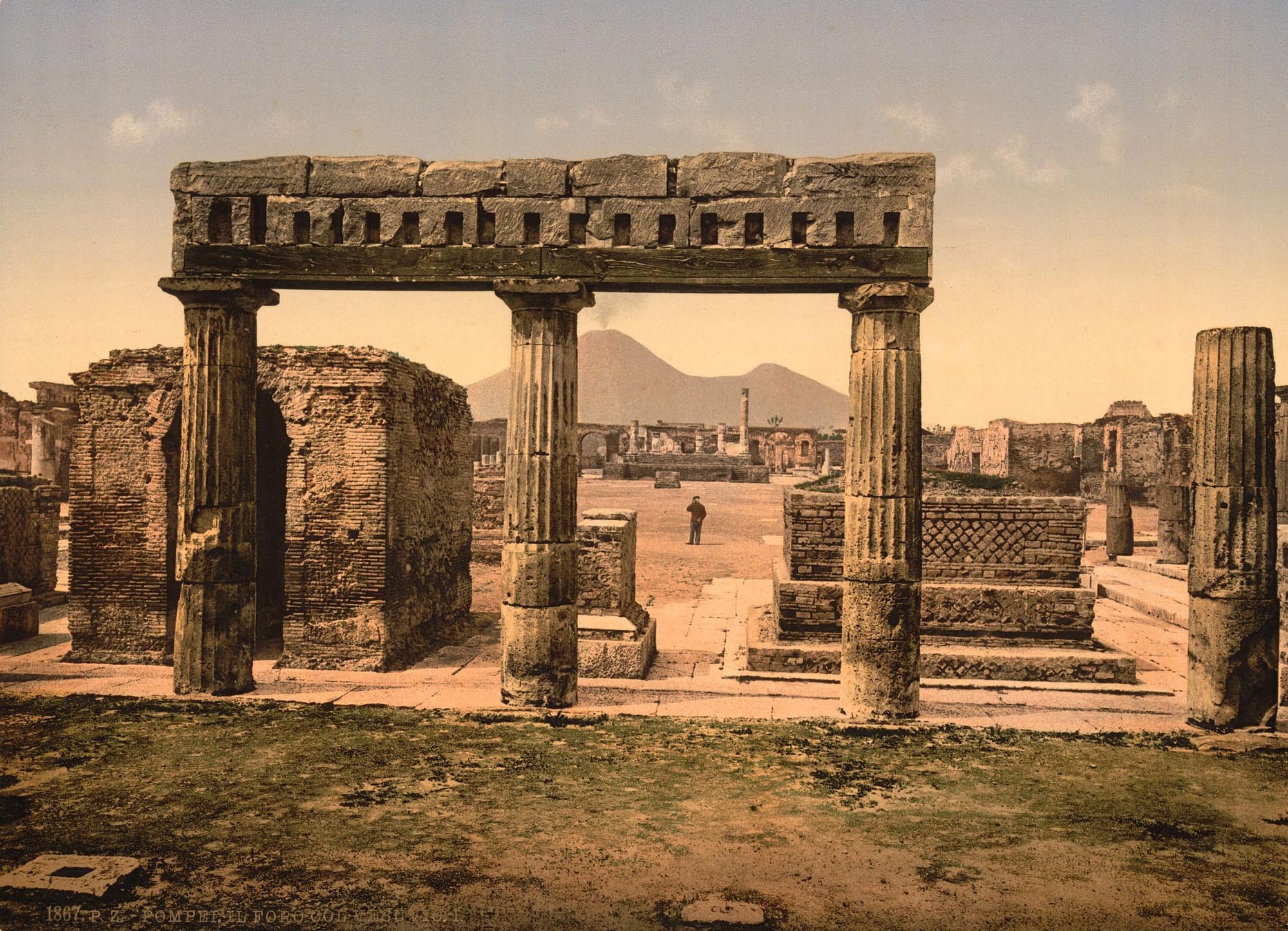

To understand Roman society, it is essential to set it against the backdrop of Rome’s political and territorial expansion. From its beginnings as a cluster of villages in Latium, the imperium populi Romani grew into an empire that spanned the Mediterranean and northwestern Europe.

The area in the power of the Roman People was a patchwork: provinces governed and taxed directly, client kingdoms serving as protectorates, and frontier zones that both repelled and absorbed outside influences. Cities (urbes) remained the focal point of civic life, exporting the model of the polis from Greece and later spreading it through Roman foundations across Spain, Gaul, Britain, and beyond.

Yet most of the population lived not in cities but in villages and small towns, maintaining local languages, cultures, and tribal loyalties. Citizenship was never about ethnicity but about rights.

By Augustus’ reign, only about 10 percent of the empire’s population were citizens, but their backgrounds were diverse—descended from Italians, Greeks, Celts, freed slaves, or soldiers rewarded for service. What distinguished them was a bundle of rights: the right to vote, marry, make contracts, own property, and pass citizenship to their children or freed slaves.

Roman law governed these lives, and demographic realities shaped them further: high infant mortality meant that almost one-third of all babies died before the age of one, about half by the age of ten. Those who survived childhood had roughly a fifty–fifty chance of reaching fifty, while only a small minority lived past seventy.

Society was structured by orders and wealth. At the top stood the emperor, followed by senators, equites, local notables, and then the vast mass of plebs, artisans, and day laborers. Soldiers could rise to prosperity, and slaves might accumulate resources and gain freedom, joining any level of society—even the senatorial elite.

Social “fault-lines” were everywhere—male and female, slave and free, rich and poor, rural and urban—but cross-class ties such as patronage, manumission, and friendship bound people together in networks of obligation and exchange. As one Roman ideal put it, relationships involved fides, trust, whether between equals or in the unequal bond of patron and client.

Women’s lives were shaped by class and biology, yet in law they were citizens with rights to property, inheritance, and family participation, even if they could not vote or serve in office. The aristocrat Claudia Pulchra lived a world apart from a peasant or tavern-keeper, but all shared the same legal framework.

Religion, meanwhile, permeated every level of life. Polytheists could recognize foreign gods as their own, and cults from Cybele to Isis were absorbed into Roman practice. Priests were not a separate caste: senators and magistrates led public sacrifices, while families, slaves, and freedmen participated in worship within the home and neighborhood.

Roman social history thus emerges as a story of mixture and assimilation. From freedmen intermarrying with citizens, to soldiers rising through the ranks, to aristocrats tracing their mythical ancestry back to the Trojan War, Rome was built on connections that crossed boundaries of class, status, and culture. The result was a society at once rigid in hierarchy and astonishingly flexible in allowing new blood to climb the ladder of power. (Roman Social History, by Susan Treggiari)

Social Classes and Status in the Empire

Roman society was built upon a steep hierarchy, where privilege and power concentrated in the hands of a tiny elite, while the vast majority occupied subordinate positions. As aforementioned, at the top stood the emperor, whose authority could be viewed both as mediator and as autocrat, bolstered by divinisation and a circle of advisers and imperial family members.

Beneath him, the senate and equestrian orders dominated politics, law, and public display, with strict rules regulating their conduct, privileges, and social prestige. Local elites—town councilors (decurions) and Greek bouleutai—mirrored this dominance in provincial settings, while apparitores (public servants), secretaries, and even wealthy freedmen could achieve local influence through benefaction.

The free populace formed a vast, amorphous group, often despised by their superiors yet tied to them through patronage, manumission, and reciprocal obligations. Occupations shaped status: while some trades brought respect, others, as Cicero observed, carried stigma.

“First, those professions that meet with general hostility, such as those of customs collection and moneylending, fail to win approval.

Next the trades of all men, who are available for hire and whose labour rather than skills are being paid for, are unworthy of a free man and are low-class.

For in these trades the pay itself is a contract of enslavement.

Also to be considered low-class are those who buy goods from retailers to sell immediately: they couldn’t make a profit unless they lied to some degree, and there is nothing more shameful than misleading others.

All craftsfolk engage in low-class skills, since a workshop has nothing respectable about it.

Those skills are least deserving of approval that serve our pleasures, ‘the fishmongers, butchers, cooks, poulterers, and fishermen’, as Terence says.

Please add to this the perfumers, ballet dancers, and the whole cabaret set.

However, skills that involve considerable intelligence or aim at some particularly useful outcome, such as medicine, architecture, and the teaching of the arts, are respectable.

… For of all things from which one can profit, nothing is better, nothing more productive, nothing sweeter, nothing more worthy of a man who is free, than farming.”

Cicero, On Duties

For the lower classes, collegia offered social protection and burial rights, and tombstones reveal pride in trades from cobblers to muleteers. Yet economic insecurity was constant, and many labored in fixed-term contracts in state monopolies such as mines. Despite rigid divisions, mobility was possible: freed slaves might rise into local notability, soldiers could advance to centurions, and even humble harvesters or traders sometimes achieved remarkable success.

This complex system produced both fault-lines—male/female, free/slave, rich/poor, town/country—and cross-class ties of patronage and friendship. Ultimately, Roman social classes reveal a society both deeply stratified and surprisingly permeable, where wealth, connections, and service to the state could reshape one’s place in the hierarchy .

Counting Lives: Demography and Population in the Roman World

The demographic realities of Rome shaped every aspect of its society. With no reliable censuses beyond Egypt and fragmentary evidence elsewhere, scholars must piece together population trends from inscriptions, papyri, and scattered references.

The empire’s growth was marked by high mortality offset by high fertility, resulting in overall population stability rather than expansion. Infant mortality was severe-as already mentioned, and average life expectancy at birth was only in the mid-twenties, though survivors of childhood often reached fifty or more.

Marriage came early, especially for women in their teens, and Augustus’ laws even sought to reward fertility among the elite. Migration, whether through colonization, military service, or the slave trade, added constant mobility within the empire. Urban centers like Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch reached populations in the hundreds of thousands, sustained by grain supplies and administrative oversight.

Ancient observers recognized that most Romans lived not in cities but in the countryside. Dio Chrysostom, reflecting on the rural poor, described how they endured a hard but honest life:

“some of them work the land, others herd flocks, and others hunt; from these labors they live, wearing simple clothing, eating simple food, and lacking the vices of the city.”

Such testimony underlines that the majority of the empire’s inhabitants were peasants, whose lives were precarious yet vital to sustaining Rome.

Despite the scarcity of exact data, the demographic picture highlights a world of fragile lives, frequent deaths, and families constantly reshaped by mortality and mobility. The rhythms of life and death, fertility and migration, formed the backdrop against which Roman social and cultural history unfolded.

Duty, and Affection: Family Life in Ancient Rome

Family lay at the heart of Roman society, a place where power, duty, and affection intersected. At its head stood the paterfamilias, whose authority in theory extended even to life and death over his children. Gaius the jurist — one of the most important Roman legal writers of the 2nd century CE emphasized this uniqueness:

“slaves are in the potestas of their masters … also in our potestas are the children whom we beget in legitimate marriage. This right is peculiar to Roman citizens; for scarcely any other people have over their sons a power such as we have” Institutes.

Yet the Roman home was not simply a site of control but of sanctity. Cicero reminded his audience:

“What is more holy, what better defended by a sense of religious awe than the domus of each individual citizen? Here the altars, here the hearths, here the household gods … this is the sanctuary, so holy to everyone that it is considered sacrilege to tear anyone away from there”.

Cicero, On His Own Home

Households could be large and complex. Plutarch tells of Aelius Tubero, whose family of sixteen shared a single hearth, embodying frugality and solidarity. More often, inscriptions reveal smaller units, but they also show the bonds of affection: grieving parents who mourned lost children, or husbands who praised wives as steadfast companions.

Marriage, divorce, adoption, and the exposure of infants reveal both the harsh demographic pressures of the ancient world and the importance placed on heirs. The household was thus both legal framework and emotional community—at once a sacred refuge, a site of authority, and a space where Romans sought love, continuity, and remembrance.

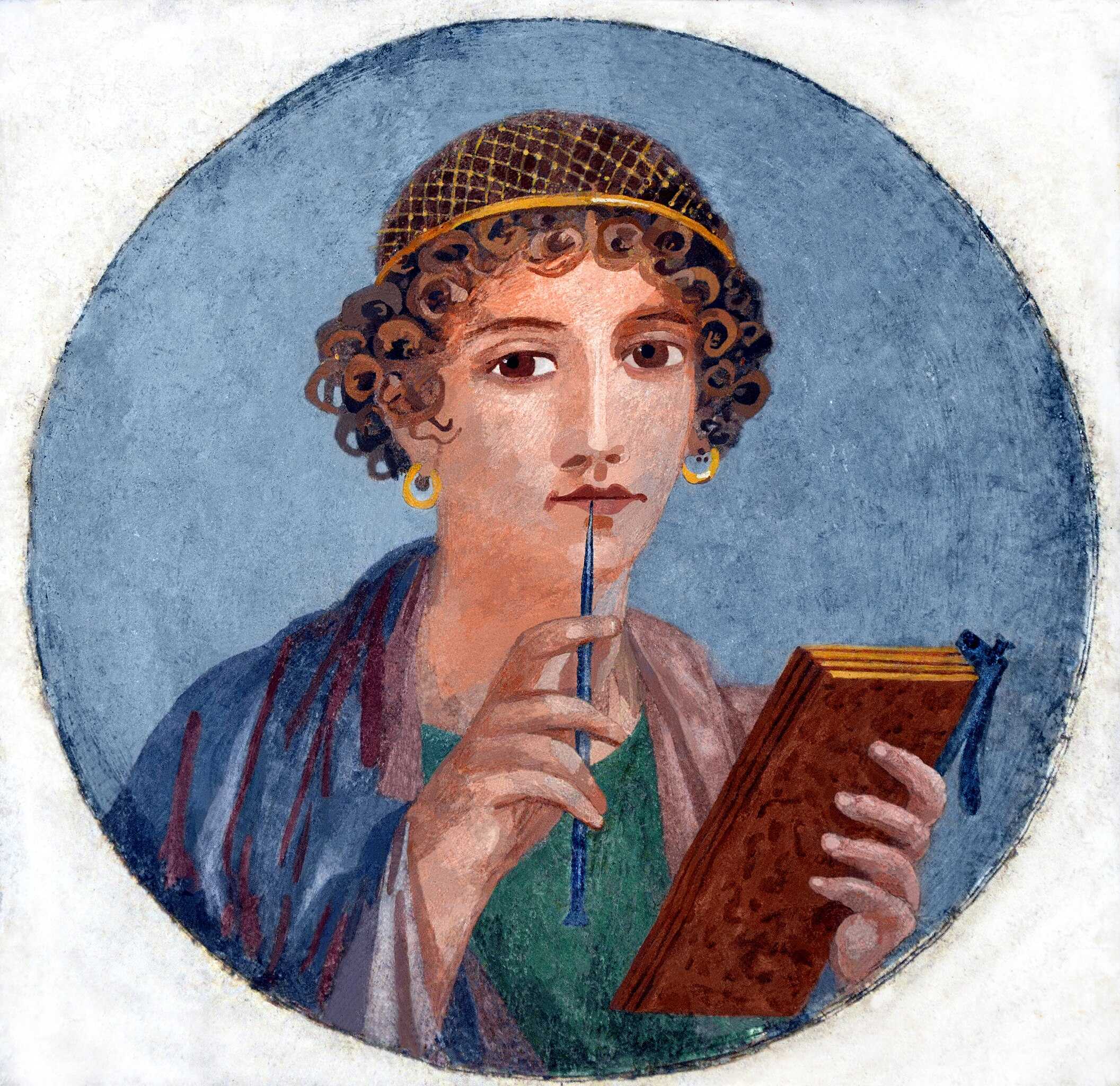

Lessons, Rods, and Rhetors: Education in the Roman World

Education in Rome began at home. Parents, nurses, and especially pedagogues—slave guardians—instilled discipline and basic learning, though children often resented their authority. Martial joked about an overbearing tutor:

“When your pedagogue, though long since freed, still clings to his charge, it’s time to say farewell”

Most children learned reading, writing, and arithmetic from a magister in public places, where noise and beatings were part of the routine. Martial complained of the racket:

“The crested cocks have not yet broken the silence, but you are already thundering with savage roar and whips … We neighbours of yours plead for some sleep.”

Punishment could be brutal—Pliny the Elder noted that children of citizens were flogged with eel skins instead of fines (Natural History). Some educators, however, advised against excessive force. Quintilian argued:

“One should lead children to decent behaviour by encouragement and advice, and certainly not by blows and humiliations”

Higher learning in grammar and rhetoric often required travel to larger cities, sometimes financed by civic trusts or benefactions. A papyrus letter from Oxyrhynchus (c. 100 CE) shows a student anxiously reporting to his father about inadequate teachers, runaway slaves, and wasted fees, revealing the struggles of studying away from home. Wealthy patrons also funded schools, though Antoninus Pius later restricted how many teachers cities could officially employ.

Teachers usually lived precariously, many being freedmen. Yet some thrived spectacularly. Suetonius tells of Remmius Palaemon, once a slave, who rose to become Rome’s leading grammarian, boasting extravagantly of his genius and wealth—though emperors Tiberius and Claudius distrusted his morals (On Teachers of Grammar and Rhetoric ). Greek intellectuals like Epaphroditus likewise prospered, amassing large libraries and estates.

Literacy levels remained uneven. Artemidorus observed that many of his clients could not read at all (Interpretation of Dreams). Soldiers with literacy were valued, but most relied on scribes for documents. Even civic inscriptions often served more as decoration than accessible records.

Education brought prestige and opened doors to public service, but it was also mocked. Petronius has Hermeros, a freedman, defend practical skills over lofty rhetoric:

“We may not be learned, but we know enough to run our lives and our trades”.

Such voices remind us that while elites prized rhetoric, for most Romans, basic literacy—or none at all—was sufficient for survival.

Crowded Streets and Crumbling Walls: The Roman Urban Experience

Roman cities were noisy, crowded, and dangerous places where housing reflected social inequality. A few elites lived in spacious domus or villas, but most inhabitants crowded into insulae, multi-storey apartment blocks notorious for fire, collapse, and squalor. Owners often prioritized rent over safety, as Cicero wryly admitted after the collapse of two of his shops:

“Not only the tenants, but even the mice have moved out”. Cicero, Letters to Atticus

Writers emphasized both the fragility of construction and the risks of urban speculation. Vitruvius described how ancient builders first used mud and branches, then improved with tiles and stone, while in his own time shoddy methods—wattle walls, timber upper floors, wooden balconies—made insulae especially flammable. Fires recurred with terrifying frequency. Tacitus, recalling Nero’s rebuilding after the Great Fire, noted how regulations now required stone walls, courtyards, and access to water:

“The height of buildings was to be restricted, and there were to be open courtyards and porticos … so that the water supply might be available to all”.

Tacitus, Annals

The spectacle of blazes became almost routine. Aulus Gellius described walking with friends when they saw:

“an apartment building alight … constructed to a great height out of many tall storeys,”

proof that:

“the returns on urban property are great, but the risks are far greater”.

Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights

Plutarch, in his Life of Crassus, accused the magnate of profiting from disaster, buying burning buildings and ruined properties until:

“most of Rome came into his possession.”

Not all dwellings were urban. Apuleius, in his Metamorphoses, gives a vivid picture of life in a poor gardener’s hut through the voice of Lucius, transformed into a donkey. He laments how both man and beast endured cold winters with little shelter or food:

“Shut in an unroofed stable, I was tortured by the unceasing cold … our meals were meagre: old and bitter greens”.

The contrasts were stark: the poor huddled in flammable shacks or crumbling insulae, while the wealthy enjoyed airy houses with gardens. Yet even the rich faced the risks of Rome’s crowded sprawl—noise, fire, flood, and collapse were constant companions of urban life. (Roman social history. A sourcebook, by Tim G. Parkin and Arhur J. Pomeroy)

Roman social history reveals a world both familiar and foreign. It was a society built on hierarchy yet bound by networks of trust and duty, harsh in its inequalities yet rich in cultural life. From the hum of the city streets to the silence of family hearths, from the discipline of the schoolroom to the blood of the arena, ordinary Romans shaped the rhythms of an extraordinary empire. Their legacy survives not only in monuments and laws but also in the traces of daily lives that still speak across the centuries.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: