How did Romans use Marketing in the Roman Empire?

In Rome’s noisy, competitive world, painted slogans and shouted announcements were more than decoration. From tavern signs and branded pottery to gladiator billboards and state-run bulletins, the Romans mastered public messaging with flair, strategy, and a touch of spectacle.

In the bustling cities of the Roman Empire, messages clamored for attention not through glowing screens or glossy magazines, but across stone walls, market stalls, and colonnaded streets. From the political slogans scrawled in Pompeii to painted advertisements for taverns, gladiator games, and lost goods, the ancient world pulsed with a surprising variety of promotional language.

Far from being silent and austere, Roman urban life was filled with carefully crafted appeals — commercial, political, and theatrical — aimed at shaping public opinion, drawing crowds, and turning a profit.

These messages, whether etched by the hand of a paid scribe or shouted aloud by a town crier, reveal a world where persuasion was public, performative, and often as strategic as it is today.

Messages on Walls, Marks on Clay: How the Romans Advertised Their World

Ancient Rome, founded in 753 BCE, evolved into the world’s first true metropolis — a city of theaters, libraries, bustling baths, and commercial brilliance. Its urban heart thrived like a grand bazaar, dense with tabernae — small shops that often featured painted signs above their doors to catch the eye of passersby.

Some of these commercial walls even doubled as paid advertising space, licensed for promotional use. Competition among retailers was fierce, and to cut through the noise, merchants employed criers to shout product names in crowded streets — an early form of audio advertising.

Still, the most powerful promotional force remained word of mouth, which traveled quickly through Rome’s dense social networks.

A possible representation of word-of-mouth marketing in the Roman Empire. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

Rome’s appetite for public entertainment also offered fertile ground for promotional spectacle. Gladiator fights, theatrical plays, and chariot races drew citizens from every social class to venues like the Colosseum, the Circus Maximus, and the Amphitheatre of Pompeii. These mass events weren’t just leisure — they were political platforms.

Wealthy elites vied for the honor of sponsoring games, using them as public displays of influence and allegiance. Public spectacle became the Empire’s version of mass media.

Celebrity culture also flourished. Gladiators, actors, and charioteers like Diocles became the icons of their age — admired, imitated, and commodified. Their fame inspired portraits, mosaics, and souvenirs, and their names held sway over the Roman imagination. The visibility of such figures was not lost on those in power, who recognized — even then — the influence of star power.

Rome’s flair for communication extended beyond arenas and marketplaces. Under Julius Caesar, the Acta Diurna (“Daily Acts”) emerged as the earliest known form of a state-run newspaper. Posted in public spaces, these bulletins informed citizens of births, deaths, court decisions, and grain supplies — curated and controlled by the state. In many ways, it was a prototype for modern media: centralized, circulated, and political.

Some scholars even argue that the essence of social media existed long before the internet. Information from public assemblies was transcribed onto papyri, copied, annotated, and re-shared. Quotes were passed along and content evolved as it traveled — much like posts on modern digital platforms.

Coins, too, became carriers of curated identity. Julius Caesar used currency to project his image and achievements — from portraits to symbols of victory — ensuring his persona reached every hand in the empire. In this, money functioned as propaganda, reinforcing power with every transaction.

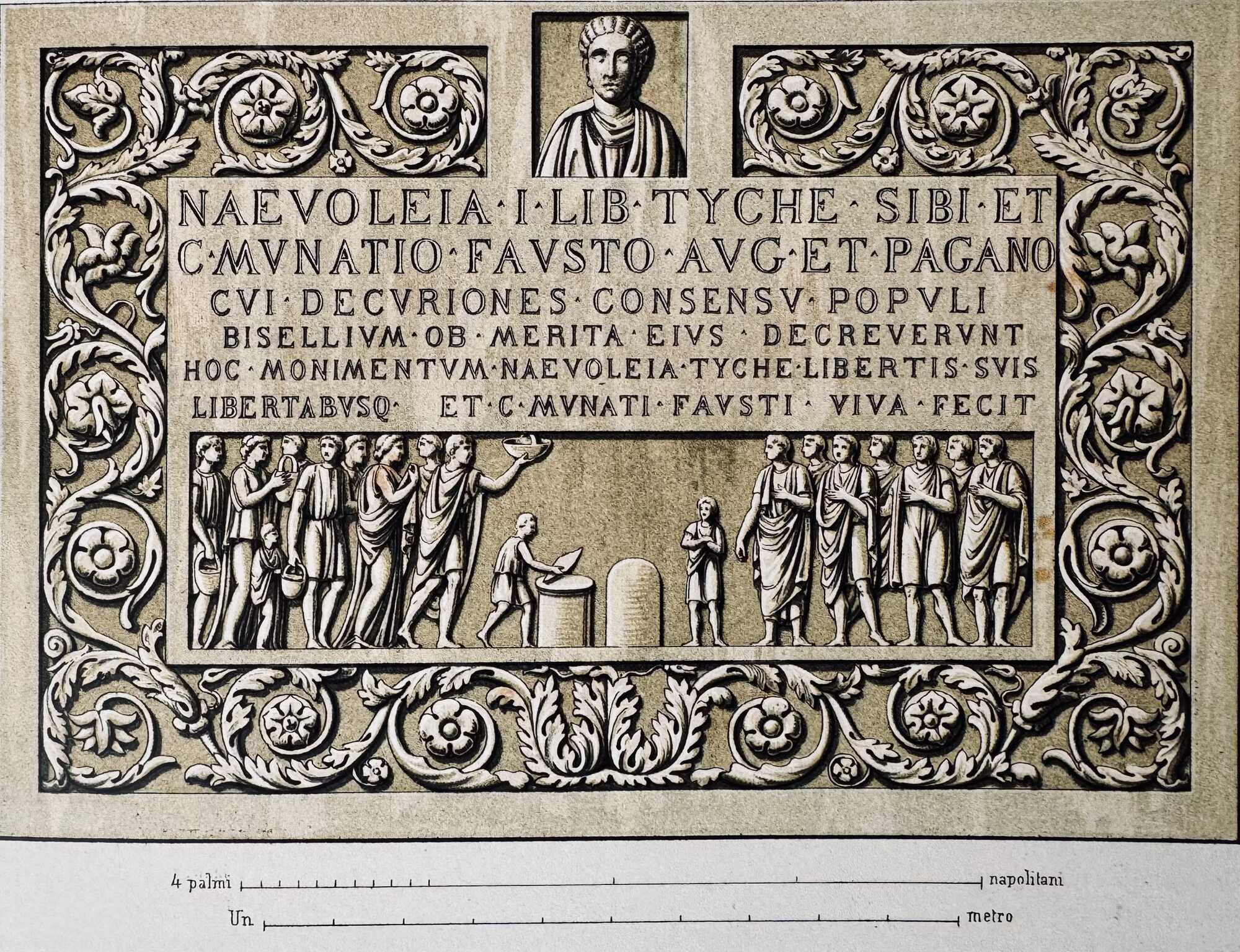

Branding, likewise, was no stranger to the Roman world. Pottery, oil lamps, bricks, and tiles often bore marks — stamps, names, or initials — identifying the maker, the workshop, or the inspector. These labels weren’t just practical; they were promotional.

Whether molded into clay or pressed into terracotta, such marks aimed to establish reputation and build loyalty. In some cases, even brand names like “Fortis” or “Communis” appeared — precursors to trademarks we recognize today.

Even Rome’s infrastructure bore signs of self-promotion. Bricks used in construction were frequently stamped, sometimes with the name of the military unit that made them, sometimes with the official overseeing the production. By the third century CE, brick production had become an imperial monopoly, and state control extended right down to the imprint in the clay.

The Roman colony of Pompeii, founded as early as the eighth century BCE, met its tragic end when Mount Vesuvius erupted in the first century CE. Yet before its destruction, the city had already embraced a lively culture of political messaging.

Archaeologists have uncovered hundreds of election-related slogans painted on its walls — early examples of organized political propaganda. A common abbreviation found at the end of these inscriptions was OVF, short for “Oro vos faciatis” (“I ask you to vote for him”).

Control over these messages often belonged to the homeowners whose walls bore them, allowing them to decide which names or slogans would appear. This practice bears a resemblance to the selective nature of personal endorsement seen in modern social media platforms.

In addition to political appeals, pictorial advertisements promoting public spectacles — particularly gladiator games — were also painted throughout the city. These ads typically included the sponsor’s name and the date of the event, serving both informational and promotional purposes.

Tickets were not sold for such events; entry was free. The spectacles themselves functioned as tools of political promotion — platforms through which Rome’s leaders could win public favor.

The exchange of influence through branding and sponsorship clearly spread across cultures in contact with Rome, showing how promotional strategy was already a shared and evolving practice. (The Origin and Historical Development of Branding and Advertising in the Old Civilizations of Africa, Asia and Europe, by Slađana Starčević)

Signs of Persuasion: Advertising Practices in Ancient Rome

Roman trade, though less central than in modern economies, still gave rise to a variety of promotional practices. Among the Roman elite, commercial activity was often looked down upon: senators, for instance, were barred from engaging in trade, with the expectation that their votes should remain free from financial influence.

Agriculture was considered the only noble occupation. As Cicero noted:

“most or all other sources of income are vulgar or ungenteel,”

with small-scale shopkeeping seen as too close to the masses. Though large-scale commerce was more acceptable, a disdain for business permeated Roman culture.

Despite this cultural posture, trade persisted, driven in part by the equestrian class and managed largely by slaves and freedmen, many of whom were foreigners. These individuals, often lacking substantial capital, would not have engaged in large-scale advertising campaigns. Yet publicity was still a part of urban life. Advertising, in its various forms, developed to suit the limitations and norms of Roman society.

Four broad categories of Roman advertising may be identified:

- Notices in news media or public bulletins

- Circulars or letters directed to individuals

- Signage for businesses and services

- Billboards and wall postings

The first category was constrained by the near-absence of formal periodicals. Prior to 59 BCE, there was no equivalent to the newspaper. Romans relied on personal letters for news, especially when posted far from the capital.

Cicero’s correspondence with Caelius Rufus exemplifies the system of private updates, mixing political commentary with social news. Some letters were circulated among others or posted in public spaces.

A class of news gatherers, known pejoratively as operarii or more neutrally as correspondents, emerged to fulfill this need for information. Though scorned by elites, their digests were widely used.

As Caelius admitted:

“You can skip the divorces, the hissings at the theater, and the rest of the trash.”

Public records evolved with Caesar’s reforms. In 59 BCE, the acta diurna were established — the first formal public reports of senatorial proceedings and daily events. Over time, the acta expanded to include items such as births, suicides, public works, and even amusing details like “the visit to the Emperor of a certain C. Crispinius Hilarus with sixty-one descendants in the direct line.”

Despite their reach, the acta did not become platforms for commercial advertising. Public interest in them was evident, especially in the provinces, but merchants did not yet see the opportunity to exploit them for promoting goods or services. Instead, dissemination of consumer trends and fashions relied more on travelers and word of mouth.

The nearest equivalent to magazines may have been the seasonal poetry volumes published by writers such as Martial, whose verses often read like promotional blurbs. Martial named publishers and booksellers, listed prices, and possibly embedded promotional content for perfumers, barbers, and others — some of whom may have paid for the mentions. References to real and fictitious tradespeople blurred the line between literary character and product placement.

Circulars, form letters, or handbills were virtually unknown — likely due to prohibitive costs and limited printing infrastructure. Signs, however, did play a role. Inns and taverns used painted or carved images — such as elephants or mythological figures — to identify themselves.

Occasionally, signs would include slogans like “One word, wayfarer: come in; a copper tablet tells you all.” A Vergilian quote on a butcher’s wall offered another imaginative flourish.

Shops displayed images of their wares: painted goats for milk vendors, Bacchus for wine merchants, dyed garments, or scenes of transactions. Though these may not have functioned like modern signs, they reflected the shop’s trade and aesthetic.

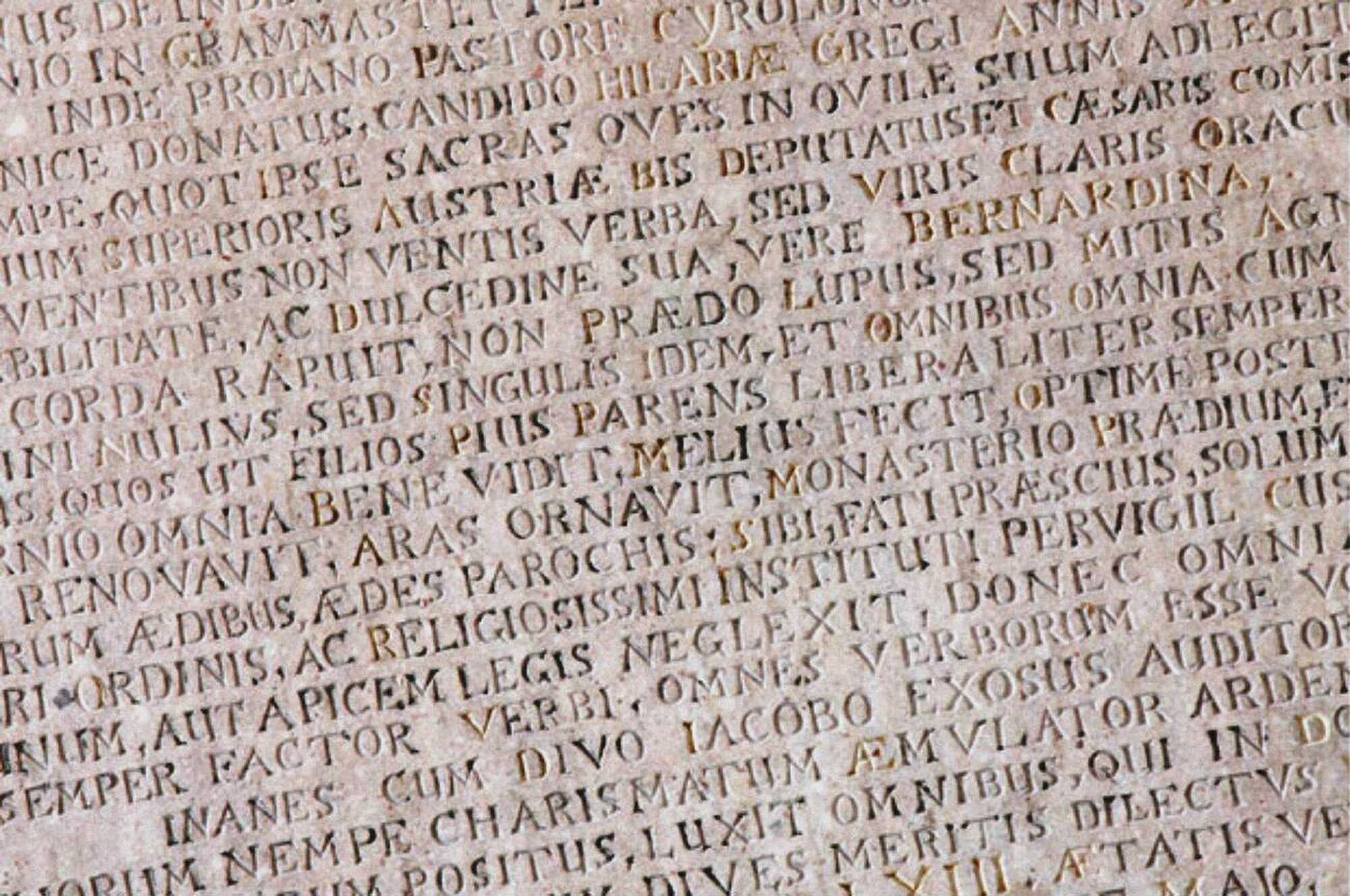

Reliefs and plaques were also used, and some shopfronts simply bore inscriptions like “Aemilius Celer lives here” — Celer being a prolific sign painter. Factory markings were rare, but goods were sometimes stamped or labeled with the names of their makers, shops, or production centers. Retail activity was spread across the city, with no centralized business districts.

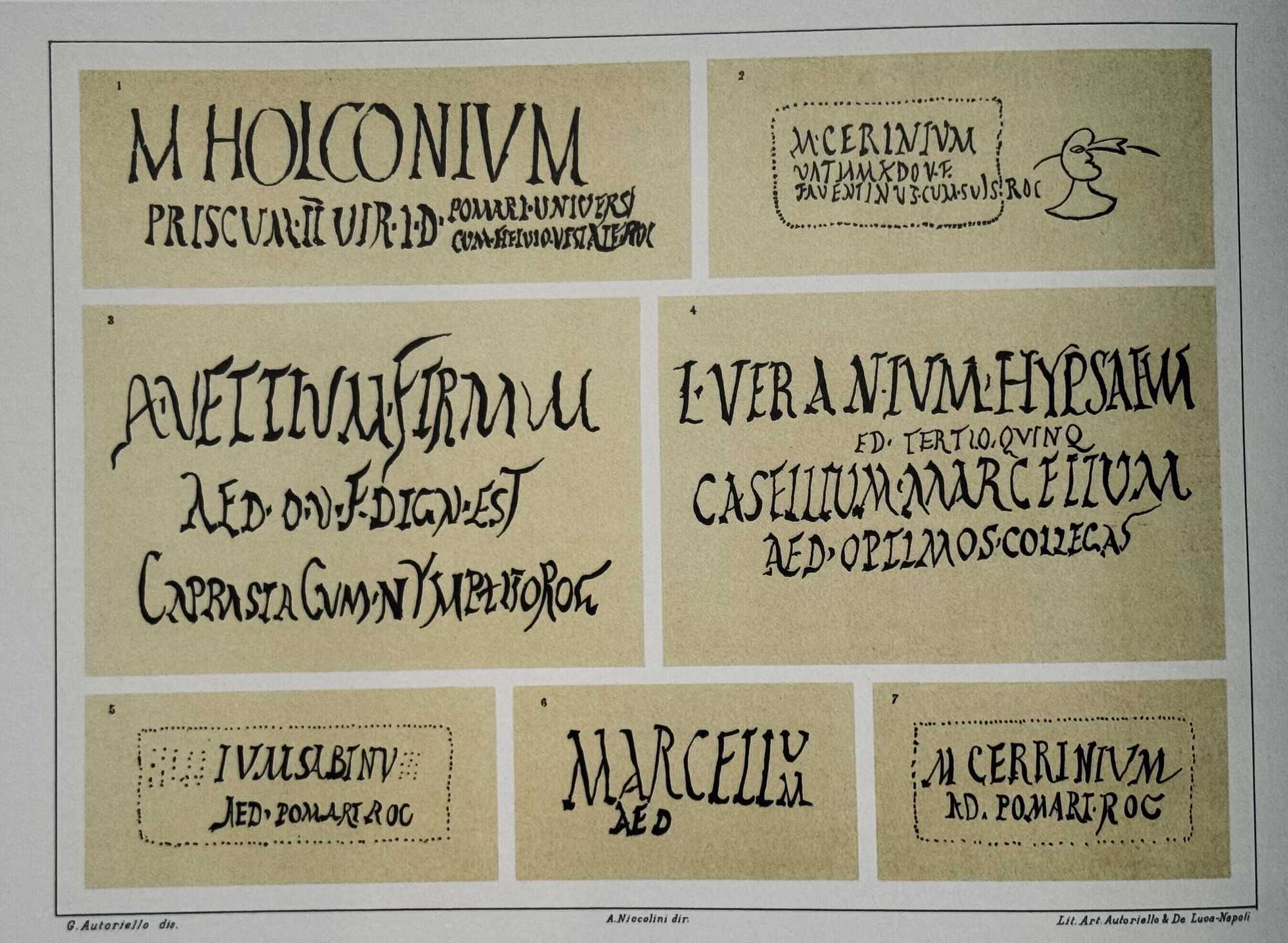

Some trades localized naturally — like the “scythemakers’ street” — and addresses often relied on nearby landmarks rather than precise street names. Billboard-style advertising was the most developed format, especially in Pompeii, where over 6,000 wall inscriptions have been found. These included everything from “for rent” signs to event announcements and political slogans.

Public buildings like the forum, basilica, and baths served as display areas. Billposting became professionalized, with names like Aemilius Celer and even whitewashers leaving signatures on their work.

At times, property owners tried to repel postings by painting snakes on their walls. Tombs along major roads were also used, with messages like: “Bill-poster, I beg you, pass this monument by. If any candidate’s name is ever painted on it, may he suffer defeat and never get an office.”

Political advertisements were particularly prominent. More than 1,500 election notices have been recovered, with recommendations from individuals, trade groups, or humorous entities like “all the sleepyheads.” Candidates were endorsed for their integrity, bread quality, or treasury stewardship.

Women occasionally joined campaigns, and messages sometimes included quotes or literary references. Literary posters outside bookshops may have echoed this model, possibly quoting from the advertised works themselves.

In assessing the relatively limited development of Roman advertising, several constraints emerge: inefficient shipping, the dominance of slavery over labor innovation, and a society with fewer product changes and less consumer novelty.

Yet the Roman citizen, with his long days spent in public spaces, had no shortage of exposure to messages. He did not need a newspaper; he was the network. And in this social, outdoor world, promotion was woven into the rhythms of daily life. Had the need arisen, the practical Roman — often called the Yankee of antiquity — would likely have met it. (Advertising among the Romans, by Evan T. Sage)

Advertising Gladiatorial Games in the Streets of Pompeii

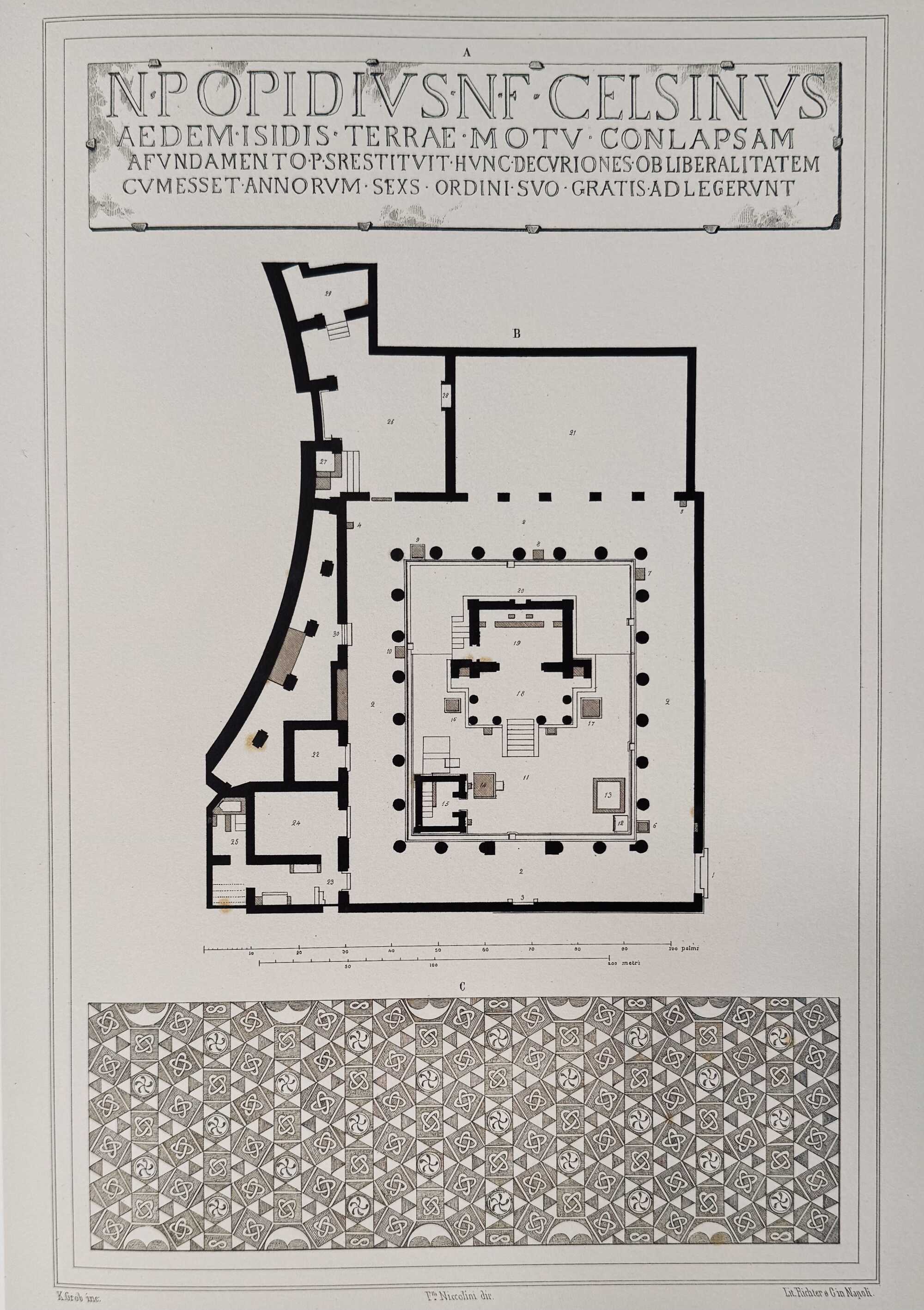

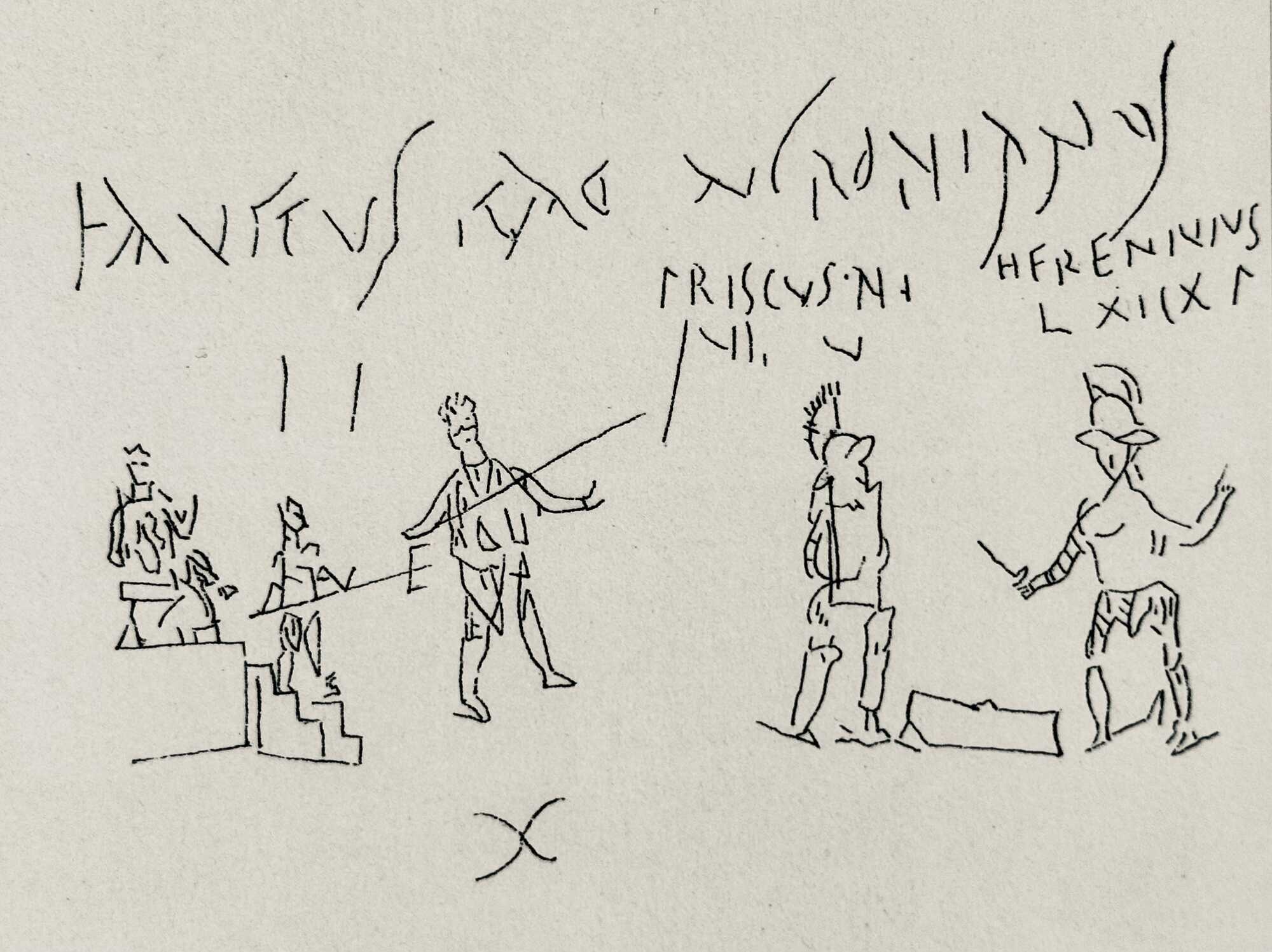

During excavations in Pompeii in the late 19th century, a striking fresco was uncovered that has since become one of the most iconic visual depictions of the Roman amphitheatre.

Painted on the wall of the peristyle in the Casa di Anicetus, the scene vividly captures the violent clash between residents of Pompeii and nearby Nuceria during a gladiatorial event in AD 59 — an episode later chronicled by Tacitus.

The composition offers more than mere drama; it includes a detailed rendering of the area around the amphitheatre, showing it as seen from Vicolo dell'Anfiteatro with the Grande Palestra prominently visible.

The painter emphasized both architectural realism and local color, depicting not only the riot but also a velarium stretched above the arena stands, merchant stalls, and the imposing façade of the Grande Palestra.

On this façade appears a prominent painted inscription: “D•LVCRETI-FELICIT[ER]”, positioned between two entryways flanked by decorated wall abutments. Accompanying this is a reference to acclamationes — public acknowledgments of the benefactors who sponsored and organized gladiatorial games.

These inscriptions, known as dipinti, were a familiar and deliberate part of the urban setting, emphasizing the significance of the games within local identity and memory. Notably, this is the only section of the fresco where the whitewashed wall has been preserved in contrast to the rest of the painted scene, drawing attention to the textual content.

The lettering style used in the fresco closely matches inscriptions discovered on the actual façade of the Pompeian Palestra, raising the possibility that what we see is not simply artistic license, but a faithful rendering of a familiar urban feature.

The scene functions not only as a dramatic record of the riot but as a tool for analyzing Pompeii’s urban landscape. The inclusion of dipinti related to gladiatorial events underscores their lasting visibility in the cityscape and their role in shaping public awareness. These painted notices were part of a consistent visual language that made spectacles like gladiator contests a permanent part of civic life.

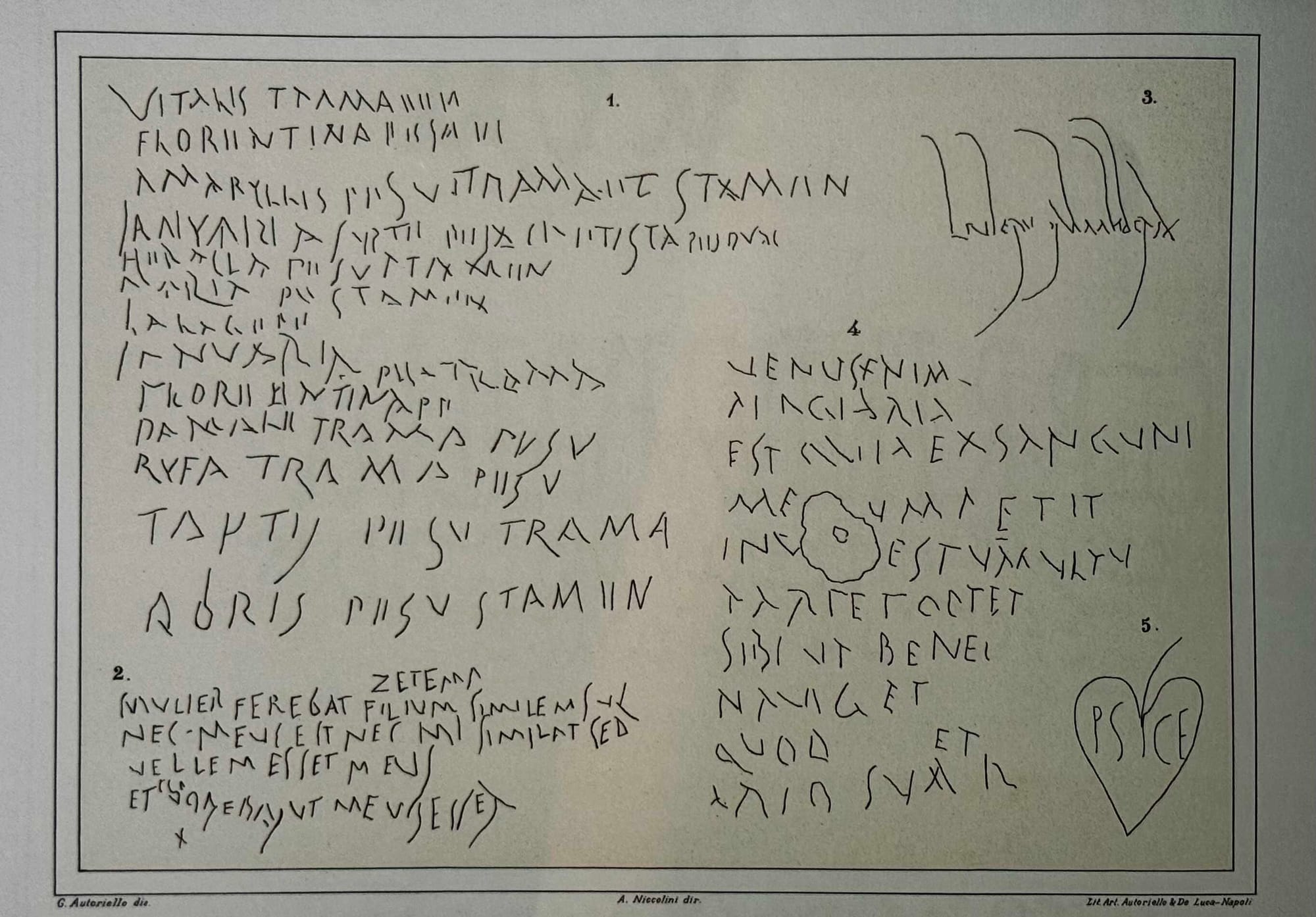

Among these painted messages were announcements called edicta munerum, advertising upcoming games and animal hunts (venationes). These were not haphazard messages but professionally produced promotional tools meant to draw large audiences.

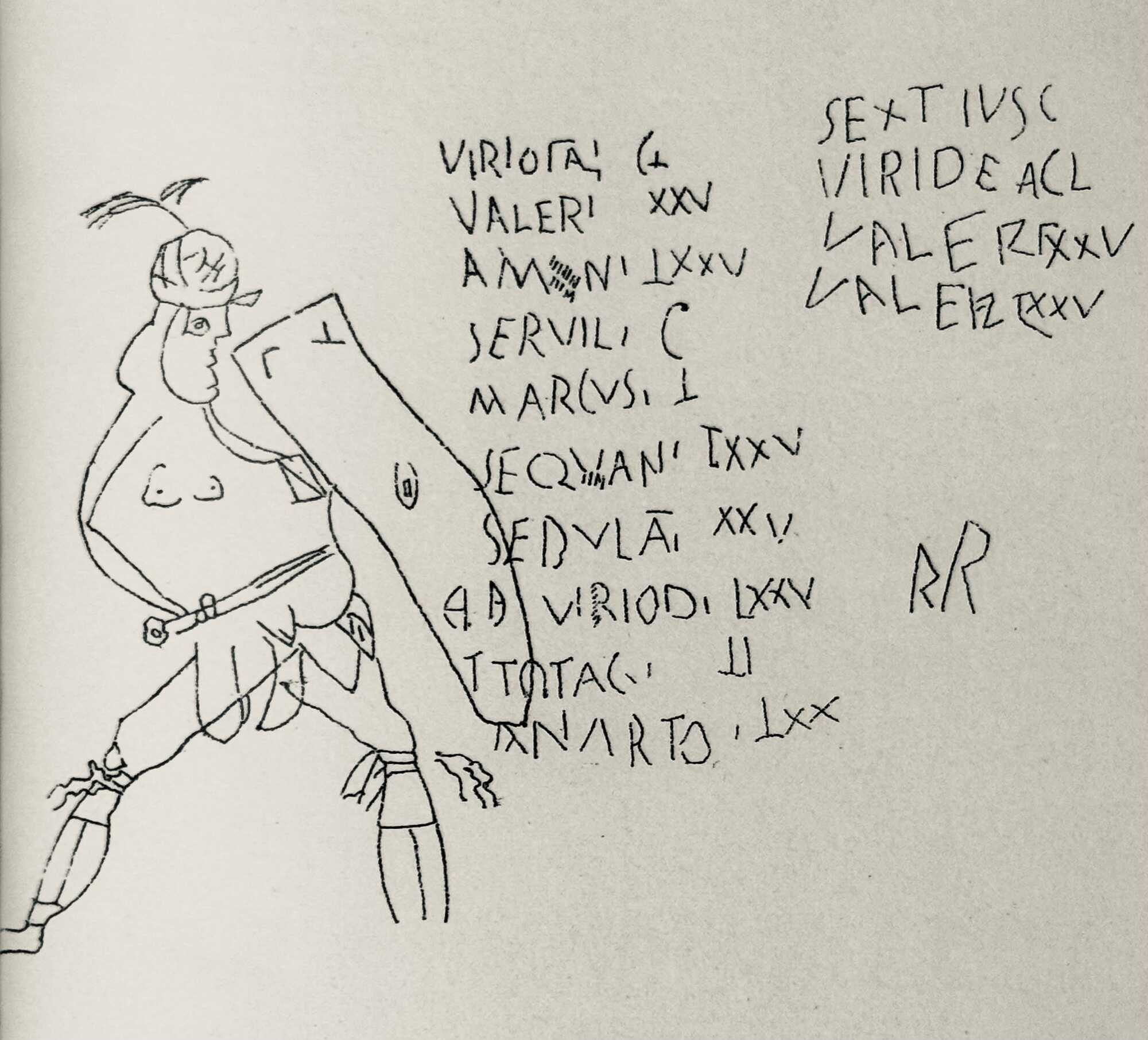

Alongside edicta were acclamationes and libelli gladiatorum — the former offering post-event praise for sponsors, and the latter serving as scratched lists of paired fighters and fight outcomes, created by spectators. These texts provided both pre-event marketing and post-event commentary, creating a feedback loop of anticipation and reflection.

While gladiatorial games are often remembered for their grand spectacle, less attention has been paid to the promotional infrastructure behind them.

These edicta, painted by skilled signwriters (scriptores), operated much like modern advertisements. Though the Latin language lacked a direct term for “advertising,” the practice was embedded in the socio-political dynamics of the time. In Campania especially, changing political landscapes and the emergence of new elites after the Social War led to a growing need to publicize games as a means of securing public favor.

Despite the general assumption that all residents already knew when and where these games occurred — since they were tied to funerals, holidays, elections, and harvests — written advertisements played a key role in encouraging attendance.

Oral announcements and word-of-mouth were not enough. Instead, painted edicta served as tools of persuasion, not just information, reinforcing public enthusiasm and legitimizing the sponsor’s status in the process.

The Pompeian evidence reveals a century-long tradition — from the late Republic to AD 79 — of using edicta as a consistent communication method. These announcements evolved alongside the politicization of what had once been private, funerary rituals.

As games transformed into public exhibitions of political ambition, advertising them became essential. From a sponsor’s perspective, information needed to spread far beyond one's social or political circle. For the spectator, the appeal depended on the quality of the show — something that needed to be conveyed compellingly.

Painted inscriptions became the most effective tool for mass advertising. Over eighty surviving examples of edicta munerum from Pompeii and its cemeteries allow scholars to study how these messages operated, where they were placed, and how they shaped public perception.

These inscriptions fall into two main categories: dipinti (professionally painted texts including edicta, programmata, and acclamationes) and graffiti (amateur messages and drawings).

While programmata — political endorsements painted on walls — lie outside the scope of gladiatorial promotions, they offer a helpful parallel. They often appeared alongside edicta and shared similar functions and locations.

Particularly notable within the dipinti category are acclamationes, emotional praises directed at the benefactors of recent games. Though visually similar to edicta, they were distinct in content and purpose, reflecting audience sentiment rather than promotional strategy.

The second category, graffiti, includes libelli — amateur inscriptions listing gladiators and match results — and figural graffiti showing fighters in action. These libelli served two functions: some may have been distributed as informational “folders” or booklets before or during events, while others were spontaneous post-event etchings made by spectators.

Though no physical copies of the “folder” type have survived, literary references provide indirect evidence for their existence. When scratched on walls, libelli served to preserve memory and emotion long after the events had ended.

All surviving edicta from Pompeii appear in their complete form, not as evolving drafts. By organizing these sources according to their function rather than their date, one can reconstruct the communication strategy behind these spectacles.

Each stage — from painted edicta to post-event graffiti — helped build anticipation, document participation, and sustain the relationship between patrons and the people they hoped to impress.

Communication as Spectacle: How Romans Engaged Their Public

The world of Roman advertising did not end with painted walls and shouted slogans. As Anna Miączewska’s study on “Communication Culture on a Mass Scale: Ancient Roman Games and Methods of Communicating with the Audience”, shows, Roman society developed a sophisticated, multi-layered system of public messaging, especially around the games.

The tools of communication were not only practical but performative — calibrated to attract, excite, and engage spectators long before the games began.

The methods fall into distinct categories: direct oral interaction (chants, cheers, and protests by the crowd), indirect oral delivery (announcements by heralds), indirect written messages (official edicta munerum, libelli, and placards), and direct written feedback in the form of graffiti and acclamationes.

This matrix gave organizers a range of channels to build anticipation, explain events, and harvest public response — not unlike today’s multi-platform campaigns.

Heralds, far from being mere criers, sometimes narrated complex stories and paraded signs to enhance the drama of the games. Placards themselves became storytelling devices, worn by the condemned and used to announce the moral lesson of a spectacle.

Painted slogans like venatio et vela erunt (“there will be hunts and awnings”) became recognizable promotional markers — effectively the brand language of the arena.

The public played an active role in this system. Spectators left emotional graffiti, praised or criticized organizers, and sometimes protested the nature of a show in real time.

Some responses, like the painting of acclamationes after particularly grand events, functioned as public endorsements of both the spectacle and the patron who paid for it. This feedback loop — direct, visible, and often spontaneous — was central to the culture of the games.

Even the logistics of edicta placement were strategic. Notices were painted along roads and on tomb facades outside city walls, catching the eye of both locals and travelers. Program leaflets (libelli), meanwhile, offered names, matchups, and timetables — part information, part memorabilia.

Miączewska's research reveals a society that not only mastered the art of communication but made it part of the performance. The games were not just advertised — they were staged long before the first blow in the arena. In Rome, publicity wasn’t a sideshow. It was part of the show.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: