How did the Romans shave? A look into men's grooming rituals

Shaving in Ancient Rome, was a painful and time-consuming process, but Romans were obsessed with hair removal for the whole body.

Shaving in Ancient Rome was not merely a personal hygiene practice but a significant cultural and social ritual that reflected one’s status and role in society. From the tools used to the techniques employed, the process of shaving held a prominent place in the daily life of Roman men.

In ancient Rome, the act of shaving was not just about personal grooming but carried significant cultural weight. The first shave of a young Roman marked his transition into adulthood, often celebrated with a gathering. Roman barbershops, or tonsoriums, served as hubs for social interaction where men would not only get shaves but also catch up on news and gossip.

The shaving process typically involved using a pumice stone to scrub away stubble followed by a novacila for a closer shave. Post-shave, perfumes and oils were applied to soothe the skin. Among the elite, having a personal barber and maintaining a hairless body was a symbol of status. It was noted that Julius Caesar had his facial hair meticulously plucked out with tweezers each day.

The Onset of Shaving in Rome

In the early Roman era, men traditionally wore uncut beards, a custom evidenced by historical accounts involving figures like M. Papirius as insulted by a Gaul, detailed in Livy's writings (V.41), and discussions in Cicero's orations (Pro Cael. 14).

It wasn't until 300 BC, according to Varro (De Re Rust. II.11) and Pliny (VII.59), that Romans began the practice of shaving, initiated by P. Ticinius Maenas who introduced a barber from Sicily to Rome. This marked a cultural shift when Scipio Africanus became the first to adopt daily shaving, a practice that gradually gained popularity, as noted by Pliny.

During the Republic, while some men trimmed and styled their beards decoratively, referred to as bene barbati and barbatuli by Cicero (Catil. II.10; ad Att. I.14, 16, Pro Cael. 14), the lower classes often couldn't afford regular shaving, leading to remarks by Martial (VII.95, XII.59). Mourning customs of the time dictated that both high and low-status men grew their beards.

Regarding societal norms, a long, unkempt beard was generally seen as a sign of neglect, something the censors L. Veturius and P. Licinius addressed by ordering M. Livius to shave and clean up before re-entering the senate after his exile (Livy XXVII.34). The first shave marked the transition to manhood and was celebrated with a festival.

This event did not have a fixed age; it usually coincided with a young man taking the toga virilis, as seen with historical figures like Augustus and Caligula who shaved at 24 and 20 years respectively. The hair from this first shave was often consecrated to a deity, exemplified by Nero who dedicated his shaved hair in an ornate box to Jupiter Capitolinus (Suet. Ner. 12).

Barbers and tools

In ancient cultures, barbers, known as κουρεύς in Greek and tonsor in Latin, played a significant role beyond mere haircutting. They were integral to personal grooming, lacking the implements found in modern homes such as combs, mirrors, and perfumes, making daily visits to the tonstrina, or barber's shop, a necessity for many. These venues served as bustling social hubs where people congregated to gossip while attending to their appearance. The barber's duties extended beyond hair cutting to include nail paring and even tooth extraction, similar to the broader role once held by barbers in England.

Barbers in ancient Rome, known as "tonsores," offered a variety of grooming services beyond just hair cutting and shaving. They worked from shops or sometimes right on the streets, providing services such as nail trimming for both fingers and toes, removing unwanted body hair, and even creating wigs. These barbers played an essential role in the daily life and hygiene of Roman Empire society.

The barber utilized a variety of tools such as knives of different sizes and shapes for cutting hair, and tweezers for plucking uneven hairs post-cut. This comprehensive approach to personal care highlights the barber's importance in ancient society, reflecting a multifaceted profession that catered to both aesthetic and practical needs of grooming and social interaction.

Roman men typically used a tool called the "novacila", a type of early straight razor, along with "pumice stones" to smooth the skin post-shave. These razors were often made from iron or bronze and required frequent sharpening to maintain their effectiveness. Wealthier Romans might have owned silver razors as a display of status.

Sometimes though, the act of shaving performed by slaves trained as barbers, especially for the elite class, highlighting a divide between the common man and the upper echelons of society.

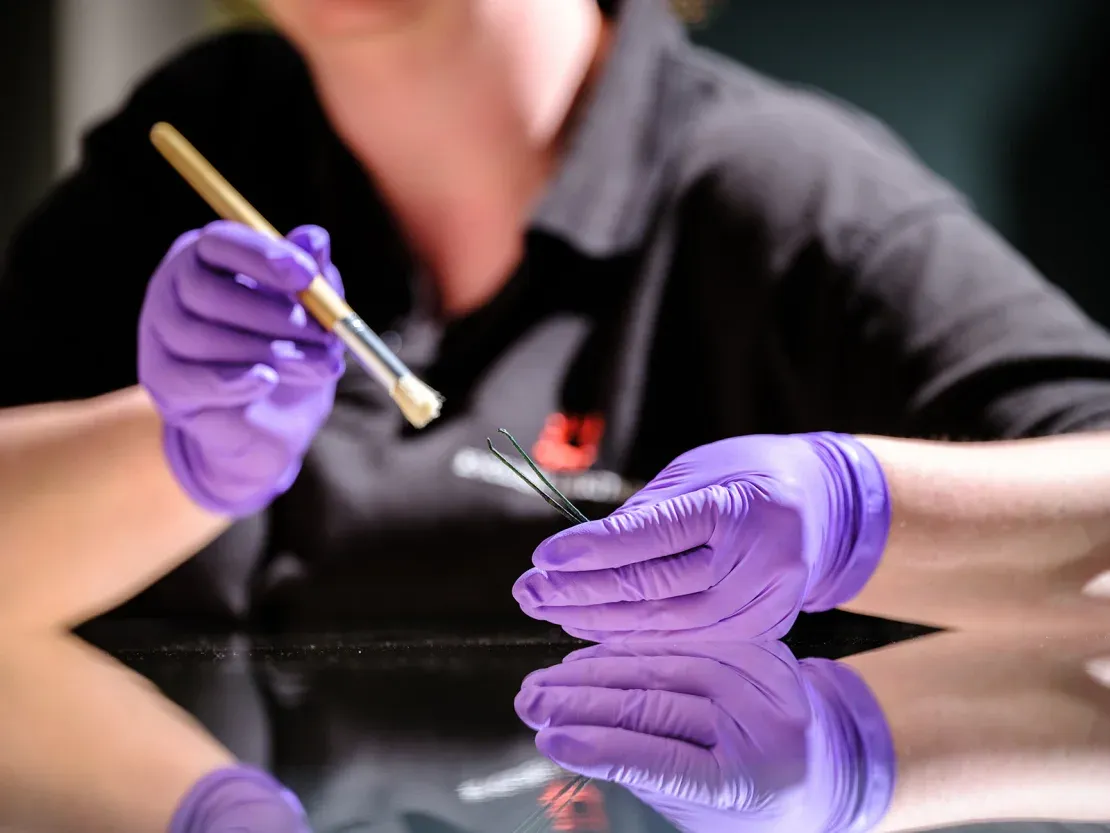

The ancient Romans' dedication to personal grooming is evidenced by their use of various tools and practices, as highlighted by English Heritage at a new museum in Wroxeter Roman City, (or Viriconium Cornoviorum, as it was known).

Among the artifacts showcased are special tweezers for removing armpit hair and other beauty-related items like strigils, perfume bottles, and jewelry. This collection offers a glimpse into the daily beauty routines that were central to Roman culture, where both men and women aimed for a clean-shaven look to distinguish themselves from non-Romans.

Painful hair removal, often done by slaves, was a common practice. The removal of body hair, including armpit hair, was not just for aesthetics but also a marker of social status and cultural identity, differentiating 'civilized' Romans from 'barbaric' tribes. This obsession with cleanliness extended to their public lives, with communal bathing being a routine activity.

The Romans used various tools in their personal cleaning kits, such as ear scoops, nail cleaners, and tweezers, which were essential for maintaining their meticulously groomed appearances. This pursuit of beauty, however, often came at the cost of discomfort, highlighting the proverb "beauty is pain" that seems just as relevant in ancient times as today.

Public recognition, wealth and popularity could be achieved by barbers. Thalamus, for example, was the barber of Nero, and went down in history for his ability. A few customers were enraged because they had been badly shaved and, as a result, hurt. But keep in mind that softeners for shaving or shaving foams were not invented yet. Shaving is described as delicate, slow, and sometimes traumatic by Latino writers.

Blades or knives, usually made in bronze, were used by the tonsors. A scissor-like contraption called forfex was formed by two blades connected by a curved part in the shape of a horseshoe, which would later evolve into contemporary scissors. Also used combs, mirrors, an iron curl, pincers, tweezers, ointments, and scents.

Techniques and Hygiene Practices

The act of shaving was typically done in the morning. Men would either visit public barbershops—places for socializing and networking—or perform the shave at home if they were wealthy enough to have personal slaves. Shaving creams or oils made from plant extracts and animal fats were used to soothe the skin and ease the shaving process.

Social and Cultural Implications of Shaving

Shaving held profound social and cultural implications in Rome. A clean-shaven face was often associated with youth and military readiness. In contrast, during periods of mourning or distress, men might grow their beards to signify their sorrow. The process of a young man's first shave (the "depositio barbae") was celebrated as a rite of passage into adulthood, often marked by a family gathering and sometimes involving a sacrifice to a deity.

Emperor Augustus was known for his meticulous grooming habits, shaving daily and ensuring his appearance was immaculate. This attention to personal grooming is reflected in the numerous statues that depict him, highlighting his commitment to maintaining an image befitting the first emperor of Rome.

In ancient Rome, the presence of barbers and the practice of shaving were relatively recent phenomena. Varro noted that ancient statues often featured bearded figures, suggesting that barbers were not a part of early Roman culture. According to Pliny, barbers only came into fashion around 300 BC. The tradition of daily shaving among Romans like Augustus, who maintained a clean-shaven appearance, was a practice that did not originate from Rome's mythical past.

Interestingly, historical accounts credit Scipio Aemilianus, who died in 129 BC, with popularizing this grooming habit. The introduction of barbers to Rome is attributed to the Greeks from Sicily, highlighting the cultural exchange that influenced Roman customs.

In Roman culture, personal grooming habits were often seen as reflections of one's state of mind. During times of personal or political crisis, prominent figures such as Augustus and Caligula would neglect their usual grooming routines as a sign of mourning or distress. For instance, after receiving news of the military disaster in the Teutoburg Forest, Augustus let his hair and beard grow for months, demonstrating his profound grief and turmoil.

He is also reported to have expressed his anguish by hitting his head against a door while calling for Varus to return the lost legions (Suetonius, Augustus, 23). Similarly, Caligula's unshaven appearance following his sister's death was a public display of his mourning (Suetonius, Caligula, 24). These actions underscored the depth of their emotional responses and were symbolic gestures that resonated with the societal expectations of their time.

In ancient Roman society, grooming and body hair had specific cultural implications, often reflecting gender norms. For example, while it was acceptable for men to remove armpit hair, removing leg hair was considered effeminate, according to Seneca in his Letters (114.4). Martial, in his Epigrams (e.g., 2.62), also critiques excessive grooming in men as a sign of effeminacy.

On the other hand, Ovid in The Art of Love, (Ars Amatoria) (1.505-524) suggests a balanced approach to male grooming. He advises men to keep their hair and beard neatly trimmed by a skilled barber, maintain a natural tan from outdoor exercises, wear well-fitting clothes, and ensure personal hygiene to be attractive without appearing overly fastidious, which he associates with feminine or effeminate characteristics.

Don’t delight in curling your hair with tongs,

don’t smooth your legs with sharp pumice stone.

Leave that to those who celebrate Cybele the Mother,

howling wildly in the Phrygian manner.

Male beauty’s better for neglect: Theseus

carried off Ariadne, without a single pin in his hair.

Phaedra loved Hippolytus: he was unsophisticated:

Adonis was dear to the goddess, and fit for the woods.

Neatness pleases, a body tanned from exercise:

a well fitting and spotless toga’s good:

no stiff shoe-thongs, your buckles free of rust,

no sloppy feet for you, swimming in loose hide:

don’t mar your neat hair with an evil haircut:

let an expert hand trim your head and beard.

And no long nails, and make sure they’re dirt-free:

and no hairs please, sprouting from your nostrils.

No bad breath exhaled from unwholesome mouth:

don’t offend the nose like a herdsman or his flock.

Leave the rest for impudent women to do,

or whoever’s the sort of man who needs a man.

Ovid, Book I Part XIV: Look Presentable

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: