What are The Ides of March and Why are they Important?

The day that Julius Caesar was assassinated has left its mark on history's face.

The Ides of March, occurring on March 15th, is a date deeply embedded in Roman history and collective memory, primarily due to the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C. This day marked a turning point, symbolizing the end of the Roman Republic and the dawn of the Empire.

A forewarning of imminent peril was given to Caesar, who had recently been declared Dictator perpetuo, ("dictator in perpetuity"), also called dictator in perpetuum, and found himself amidst increasing hostility in Rome. Although Caesar's fall precipitated the decline of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Empire, the term "Ides of March" is famously linked to its depiction in William Shakespeare's drama "Julius Caesar."

Understanding the Roman Calendar

Rather than sequentially numbering the days from the beginning to the end of the month, the Romans used a system of counting backwards from three critical points within the month:

- The Nones - Nonae (either the 5th or 7th, depending on the month, and occurring eight days prior to the Ides)

- The Ides - Idus (falling on the 13th for most months but on the 15th for March, May, July, and October)

- The Kalends - Kalendae (which marked the start of the following month)

The Significance of the Ides of March

The Ides were intended to align with the full moon, underscoring the Roman calendar's lunar origins. March, or Martius, served as the initial month of the Roman year up until the mid-2nd century BC. This is evident in the names of the months from September to December, which originally aligned as the seventh to tenth months, respectively, but now occupy different positions in the modern Gregorian calendar.

In the oldest Roman calendar system, the Ides of March marked the year's first full moon. Positioned as a significant day within the month, the Ides became associated with various monthly obligations, including the due date for debts and rent payments.

The month of March, named after Mars, the god of war, began with celebrations for Mars but the Ides of March were dedicated to Jupiter, the chief deity of the Romans. During the Ides, a specific ritual involving the sacrifice of a sheep, known as the "Ides sheep," by Jupiter's high priest took place.

This procession and sacrifice occurred along the Via Sacra to the arx. (Arx is a Latin word meaning "citadel". In the ancient city of Rome, the arx was located on the northern spur of the Capitoline Hill, and is sometimes specified as the Arx Capitolina.) Despite the introduction of January and February as the first months of the year, March retained its significance with several ceremonies, one being the Feast of Anna Perenna.

Anna Perenna was an old Roman deity of the circle or "ring" of the year, as indicated by the name (per annum).

Anna Perenna silver denarius Roman coin. Credits:

Otto Nickl, CC BY-SA 4.0, Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

This feast marked the conclusion of the new year's celebrations, characterized by public festivities such as picnics, drinking, and general merriment. Additionally, the Ides of March included the Mamuralia - Sacrum Mamurio a ritual possibly related to the theme of expelling the old year, symbolized by beating an old man dressed in animal skins.

The Sources of Caesar’s Final Years: Evidence, Myths, and Political Lessons

The final years of Julius Caesar’s life, particularly the two years leading up to his assassination on the Ides of March in 44 BCE, are illuminated through three primary types of evidence. The first and most valuable category consists of contemporary sources. Cicero’s correspondence provides an extensive firsthand record, though disappointingly sparse for the five months Caesar spent in Rome before his death.

Additional contemporary works include speeches by Cicero, Book 8 of De Bello Gallico (written posthumously by Aulus Hirtius), and Caesar’s own commentaries on the Civil War. Other documents, such as Sallust’s De Republica Ordinanda and numismatic evidence, further contribute to our understanding.

The second category comprises lost contemporary sources that can be partially reconstructed. These include the Catones and Anticato, polemical works produced in the wake of Cato’s suicide, as well as slander and propaganda circulated by both Caesar’s assassins and his defenders. Personal recollections, such as those of Calpurnius Bibulus regarding his stepfather Brutus, and the writings of hostile figures like Tanusius Geminus, reflect the deep political divisions of the time.

The third category consists of later historical accounts by authors like Velleius Paterculus, Plutarch, Suetonius, Appian, and Cassius Dio. These later narratives, though partially based on contemporary evidence, are also influenced by historical imagination and the political contexts of their authors. While often useful, they present the risk of creating a composite and sometimes misleading historical picture.

The Political Lessons of Caesar’s Murder

Caesar’s assassination, while tragic, imparted two key lessons. First, it demonstrated that Republicanism was not yet dead. Caesar had assumed too readily that the Republic was a thing of the past, much as he had mistakenly believed Gaul to be conquered in 57 BCE.

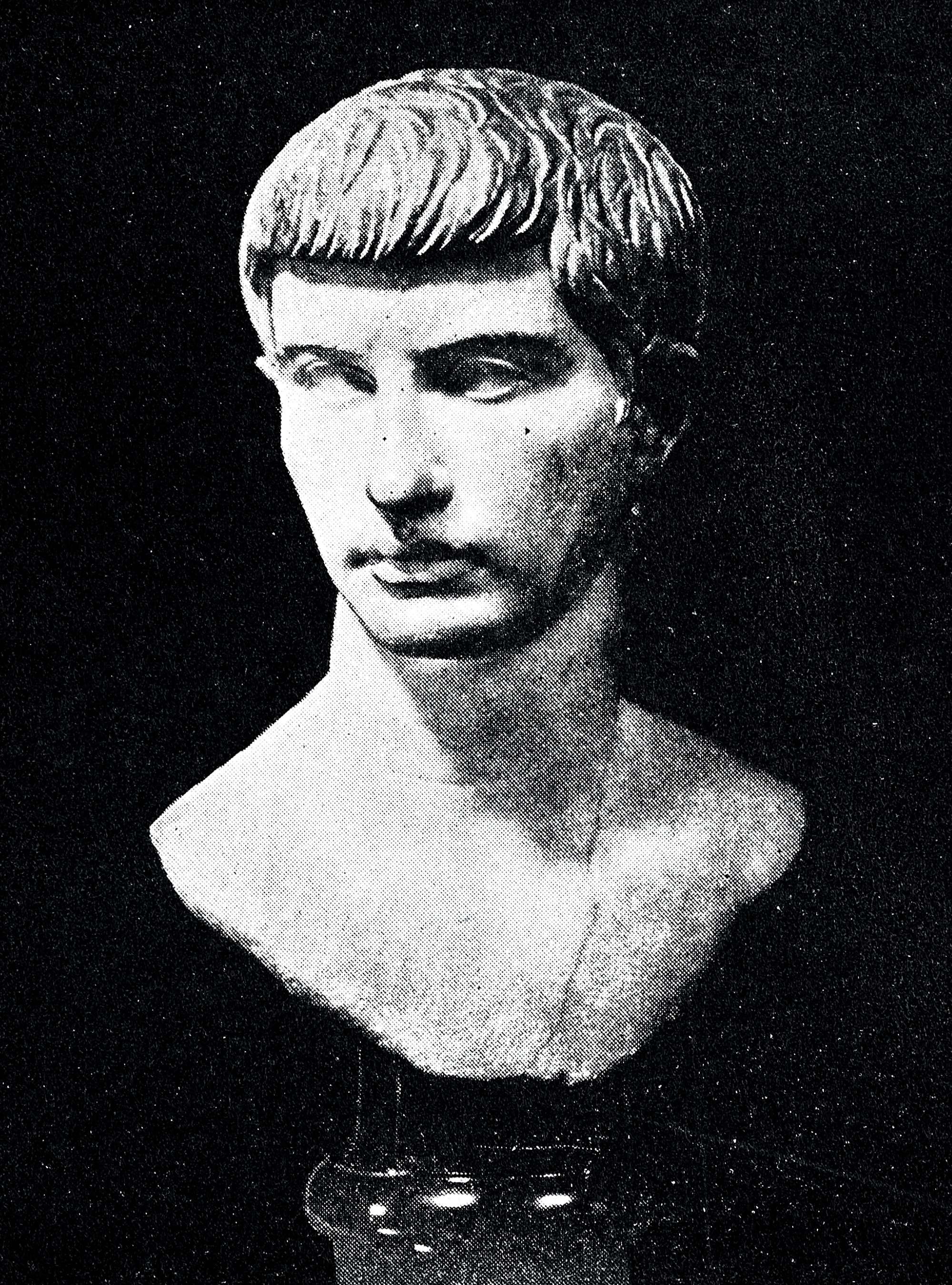

The coup de grâce to Republicanism would require further violence, proscriptions, and ultimately, the brutal pragmatism that Caesar’s heir, Octavian, would embrace.

Cameo of Octavian, later Emperor Augustus. Credits: Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0 1.0

Second, the assassination underscored that an authoritarian regime in Rome could not be as openly frank as Caesar’s had been. Unlike Caesar’s direct and sometimes careless approach to power, Octavian (later Augustus) learned the necessity of maintaining a republican façade while exercising absolute control.

For Caesar personally, his assassination may not have been as overwhelming a tragedy as it might seem. Having dismissed his Spanish bodyguard and living without military protection, he appeared unconcerned about the possibility of assassination.

Suetonius and Plutarch report that he had even expressed a wish for a sudden death. Whether these accounts are entirely accurate or not, they underscore that Caesar, at least outwardly, did not fear the end.

The Conspiracies That Never Were

Following Caesar’s murder, a variety of retrospective plots were invented to justify the assassination. Stories emerged that various individuals had planned to kill Caesar earlier but had failed for circumstantial reasons. Cassius was said to have plotted against him at Tarsus in 47 BCE but was thwarted by geography.

In 46 BCE, assassination attempts supposedly occurred in Rome, including an alleged plot by Antony, though contemporary sources like Cicero’s letters remain silent on such melodramatic claims. Trebonius, another of the assassins, was later said to have plotted against Caesar in 45 BCE with Antony’s cooperation, but Antony allegedly lost his nerve at the last moment.

Similarly, posthumous justifications for the murder proliferated, suggesting that Caesar had to be killed “in the nick of time” to prevent some imminent tyranny. Yet, concrete evidence for these claims is lacking. The most persistent myth was that Caesar sought to become king, an idea linked to an alleged Sibylline prophecy that Parthia could only be conquered by a Roman king. However, even ancient sources like Cicero’s De Divinatione dismissed this prophecy as a fabrication.

The Myth of Caesar’s Monarchical and Divine Aspirations

While Caesar undoubtedly accumulated unprecedented honors, the claim that he sought kingship or divine status remains dubious. He had statues in temples, was voted a Flamen (though never initiated), and was hailed as Pater Patriae, but he consistently rejected the formal title of king.

The famous episode at the Lupercalia, where Antony attempted to crown him, ended with Caesar throwing the diadem aside, a gesture his critics could hardly reconcile with a desire for monarchy.

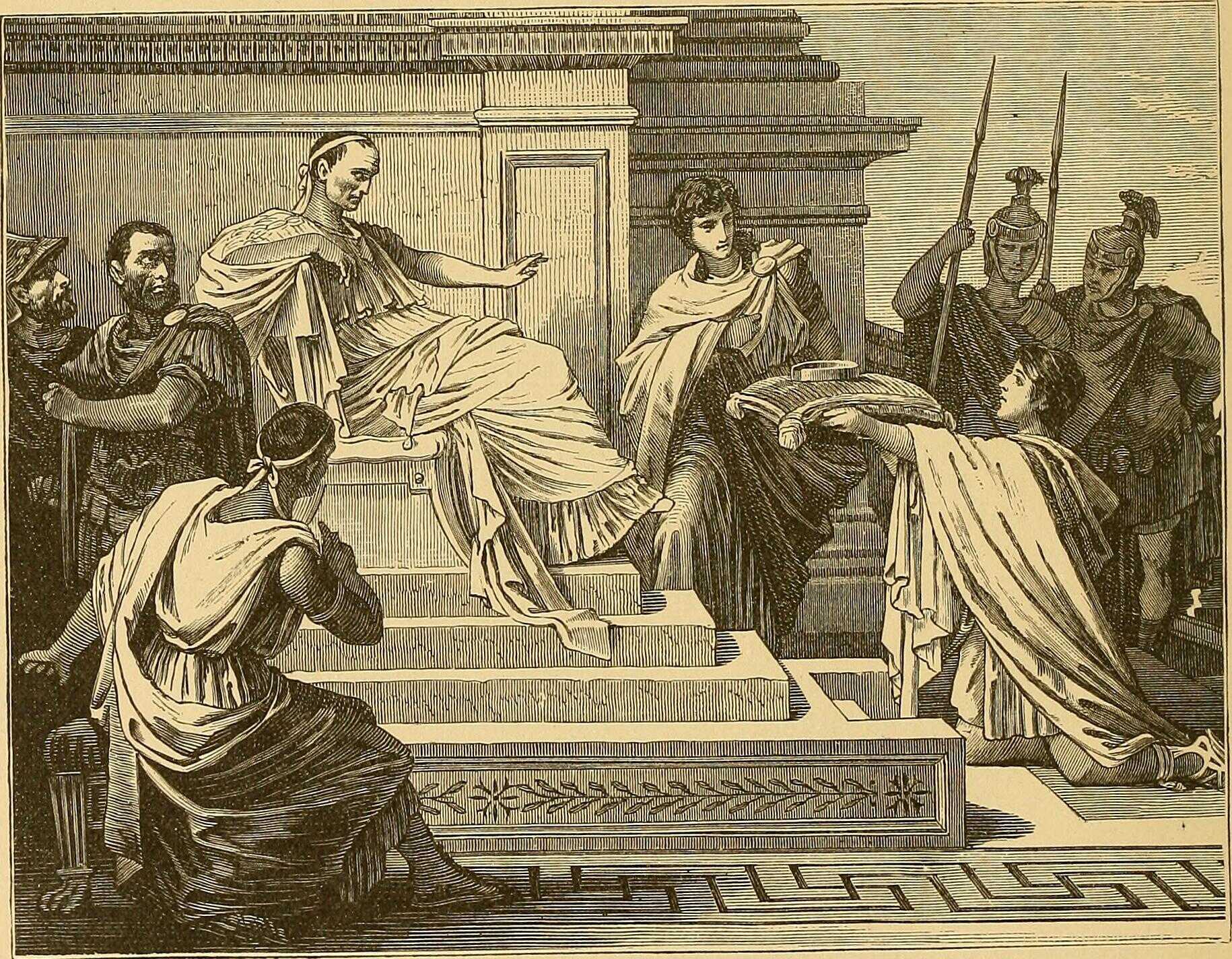

A gravure depicting Julius Caesar refusing the diadem crown offered to him by Mark Antony, as a sign of his status as king. Public domain

The idea that he planned to elevate Cleopatra as queen and legitimize their alleged son, Caesarion, was another fabrication. The decree supposedly allowing Caesar to recognize any offspring as legitimate was never proposed in his lifetime. The story, attributed to the tribune Helvius Cinna, conveniently lacked a firsthand denial—Cinna was torn to pieces by the mob at Caesar’s funeral just days later.

As for Caesarion himself, the lack of any mention of his existence in Cicero’s extensive correspondence is striking. Some scholars, like Jérôme Carcopino, have even argued that he was born after Caesar’s death and was not his son at all. Given Caesar’s long history of marriages and affairs without producing other known children, the idea that Cleopatra alone bore him an heir seems highly suspect.

The Growing Rift Between Caesar and the Aristocracy

The perception that Caesar had changed in his final months—becoming more arrogant, unapproachable, and autocratic—has been argued by some historians. However, there is little direct evidence to support this view. Rather than Caesar changing, it was the failure of the system to change that likely led to his murder.

After the decisive victory at Munda in 45 BCE, the expectation was that Caesar would transition to a more traditional mode of governance. Instead, he continued to rule as a military dictator, issuing commands from above and sidelining the Senate. For Rome’s conservative elite, this was intolerable.

The resentment among the aristocracy was compounded by Caesar’s reliance on men they considered unworthy—figures like Balbus, Oppius, and Hirtius—while traditional senatorial voices were ignored. Cicero himself, despite wishing to act as Caesar’s philosophical advisor, found his suggestions unwelcome.

Brutus, Porcia, and the Path to Assassination

One of the most fascinating aspects of the conspiracy is the transformation of Marcus Junius Brutus from a loyalist to Caesar’s murderer. In August 45 BCE, Brutus still believed that Caesar intended to restore the Republic. Cicero, however, was already urging him to remember his lineage:

“Where is that Brutus and Ahala I saw in your Parthenon?”

—a reference to his supposed ancestors who had famously opposed tyranny.

Brutus’ marriage to Porcia, the daughter of Cato the Younger, was likely a turning point. Having been raised under the influence of the fiercely Republican Cato, Porcia’s presence in Brutus’ life must have reinforced his sense of duty. By late 45 BCE, as it became clear that Caesar had no intention of restoring the Republic, Brutus’ allegiances shifted. While Cassius, the conspirator with a more radical history, was a key figure in the plot, it was Brutus’ moral weight and prestigious name that made the assassination feasible. (The Ides of March, by J. P. V. D. Balsdon)

The Ides of March: Planning, Execution, and Unintended Consequences

The assassination of Julius Caesar on March 15, 44 BCE, was not an impulsive act but the result of careful planning, political urgency, and miscalculations by the conspirators. The decision to strike on the Ides of March was shaped by Caesar’s upcoming departure for Parthia, a rumored attempt to declare him king, and the symbolism of the chosen location—the Curia of Pompey.

The conspirators believed their actions would restore the Republic, but instead, their choices set in motion the collapse of the very system they sought to protect.

Why the Ides of March? The Urgency Behind the Assassination

The conspirators acted with a sense of urgency. The conspiracy was widely known, and further delay risked discovery. More crucially, Caesar was scheduled to leave Rome for his Parthian campaign on March 18. If he left, their window to act would close.

A rumor circulating in Rome added even more pressure: it was said that L. Aurelius Cotta, a member of the XVviri sacris faciundis, (Quindecimviri sacris faciundis, "Fifteen Men for the Performance of Sacred Rites" was a collegium of priests in ancient Rome responsible for overseeing the Sibylline Books and interpreting them in times of crisis), planned to announce that the Sibylline books had foretold that only a king could defeat the Parthians.

Whether this prophecy was real or fabricated, the conspirators believed it, fearing that Caesar was about to assume the title of rex. This, they thought, would permanently end the Republic.

Compounding their anxiety, Caesar was scheduled to address the Senate on the Ides regarding objections raised by Mark Antony over Dolabella’s election as consul. This was a crucial issue, and Caesar’s presence at the Senate was guaranteed. Thus, the Ides of March became the ideal moment to act—a decisive strike before any irreversible political developments could take place.

Alternative Assassination Plans

Before settling on the Curia of Pompey, the conspirators considered multiple assassination scenarios:

- During the Comitia (public assembly) on the Campus Martius, where they planned to push Caesar off a bridge and kill him.

- On the Via Sacra, a location Caesar frequently visited as pontifex maximus.

- During gladiatorial games, using the presence of weapons as cover.

- At the entrance to Pompey’s Theatre, before he entered the Senate.

Once the Senate meeting was announced, the Curia of Pompey became the most logical choice, as it ensured Caesar would be isolated, unarmed, and vulnerable. It also carried symbolic weight, with Caesar falling at the base of Pompey’s statue, reinforcing the perception that the Republic was being avenged.

The Role of the Festival of Anna Perenna

The Ides of March coincided with the Festival of Anna Perenna, a celebration held in the Campus Martius. This festival, which involved drinking, singing, and outdoor feasting —as already mentioned— drew much of the urban population away from the city center, reducing the risk of an immediate public backlash.

At the same time, gladiatorial games were held at Pompey’s Theatre, drawing further attention away from the conspirators’ actions. Gladiators were stationed nearby, ostensibly for the games, but also as backup in case resistance arose. Decimus Brutus ensured that their presence would not arouse suspicion, claiming they were there to resolve a contract dispute over a gladiator’s services.

Caesar’s Last-Minute Hesitations and Omens

The assassination almost did not happen. Calpurnia’s nightmares deeply unsettled her, and she pleaded with Caesar not to attend the Senate. The haruspices, examining a sacrificial liver, warned of bad omens, advising him to stay home. Initially, Caesar considered canceling his Senate appearance, fueling rumors that he would remain at home that day.

Even his golden chair was removed from the Senate chamber, anticipating his absence. However, Decimus Brutus intervened, convincing him that a full Senate awaited him and that it would be dishonorable to disappoint them. Reluctantly, Caesar agreed and left his house late—around the fifth hour (10–11 AM), much later than usual. (The Ides of March: Some New Problems, by Nicholas Horsfall)

The Aftermath of Assassination: The Journey of Caesar’s Body and the Role of Medicine in the Ides of March

As Julius Caesar fell beneath the statue of Pompey on that fateful Ides of March, 44 BCE, the conspirators stood over his lifeless body, their daggers dripping with his blood. The Senate chamber, filled with the echoes of his final breath, quickly emptied as chaos erupted in the streets of Rome.

While the assassins saw themselves as liberators, they had left behind a gruesome spectacle—one that would set in motion a chain of events leading to the fall of the Republic.

A possible representation of the dagger that delivered the deadly strike from the murderers to Julius Caesar. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

Among the many accounts of that day, Suetonius alone records a crucial, often-overlooked detail: the physician Antistius medicus was summoned in the hours after the murder. His role was not to save Caesar but to examine his body—to determine what had truly killed the Dictator. This medical inquiry would not only shape the narrative of the assassination but also foreshadow the legal and political battles that followed.

The Journey Home: A Widow’s Lament and a Public Display

After the assassins had fled, three slaves gathered Caesar’s lifeless body, carefully placing it in a litter. But there was no dignity in his final journey—his arm hung limply over the side, a shocking visual of vulnerability for the once-mighty general. The procession through Rome was not discreet; as Nicolaus of Damascus tells us, the curtains of the litter were left open, exposing the brutal wounds to the Roman people.

Awaiting him at home was Calpurnia, his devoted wife, who had spent the morning in anguish, pleading with Caesar not to go to the Senate. Her dreams had been filled with terrifying omens, and now, as she ran out to meet the body, her worst fears had materialized. She was now a childless widow, the wife of a man whose fate had been sealed by betrayal and ambition.

The Physician’s Verdict: Antistius and the Forensic Examination

As Rome reeled from the assassination, the physician Antistius medicus arrived at Caesar’s house in the late afternoon. Unlike modern forensic examiners, Antistius was not conducting an autopsy but a politically significant assessment. His findings would influence how Caesar’s death was understood—and whether it would lead to legal action against the conspirators.

After carefully inspecting the wounds, Antistius reached a startling conclusion: despite the twenty-three stab wounds inflicted upon Caesar (or thirty-five, according to Nicolaus), only one was fatal. It was a single, deep wound to the chest that ultimately ended the Dictator’s life.

This verdict carried profound implications. If only one wound had been fatal, who had delivered the death blow? The conspirators had acted as a collective, but Antistius' assessment suggested a hierarchy of guilt—someone had struck the decisive wound, and this revelation had the potential to divide the assassins as accusations flew.

Medicine and Politics in Rome: A Greek Legacy

The presence of Antistius at Caesar’s home also sheds light on the evolving role of medicine in Roman society. By the first century BCE, Greek-trained physicians had firmly integrated into elite Roman households, despite earlier Roman skepticism toward foreign doctors.

A century earlier, Cato the Elder had warned his son never to trust Greek physicians, believing they sought to poison Rome. Yet by Caesar’s time, Hellenistic medicine had become indispensable to the aristocracy. Wealthy patricians employed personal doctors, who traveled with them, prescribing treatments ranging from medicated wines to passive exercises like horseback riding and singing.

Yet, for all his power, Caesar did not keep a personal physician in his entourage—an unusual omission for a Roman statesman of his stature. The only previous mention of a medicus in Caesar’s life comes from Suetonius’ account of his capture by pirates in the 70s BCE, when he was accompanied by an anonymous doctor.

But no official record exists of a personal physician attending to him in Rome. It is possible that Antistius was not connected to Caesar at all but was called upon simply due to his forensic expertise.

The Legal Ramifications: Was Justice Possible?

The timing of Antistius' examination suggests that some of Caesar’s allies hoped for a legal case against the assassins. The memory of the de vi trial of Milo—who had been convicted for the murder of Clodius Pulcher in 52 BCE—was still fresh in Roman minds. Perhaps a similar charge could be brought against the conspirators.

Had events unfolded differently, Caesar’s murderers might have faced a formal trial in Rome. But history took a different course. Instead of standing before a court, Brutus, Cassius, and their fellow assassins would find themselves hunted across the Roman world, forced to fight for their survival.

On March 17, the Senate reached a temporary compromise:

- Caesar’s acts would remain valid, avoiding the complete undoing of his rule.

- The assassins would be granted amnesty, ensuring that no immediate legal proceedings would be held.

This agreement, however, was merely a pause before the storm. The public funeral, filled with outrage and emotion, turned the Roman people against the assassins. Octavian, Caesar’s adopted son, would use this fury to consolidate power, eventually leading to the Battle of Philippi (42 BCE), where Brutus and Cassius met their fates.

The End of an Era: From Republic to Empire

Caesar’s assassination was meant to restore the Republic, but instead, it accelerated its demise. The Republic’s legal structures—trials, Senate decrees, and forensic investigations—could not contain the fallout of his murder.

Octavian, once just a name in Caesar’s will, emerged as the avenger of his adoptive father. In time, he would become Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, and his regime would ensure that Caesar’s legacy endured. He even framed his vengeance in legal terms, claiming in the Res Gestae that he had avenged Caesar “with appropriate judicial procedures” (iudiciis legitimis ultus).

Calpurnia, the widow who had foreseen the disaster, disappeared from history, her grief lost to time. The conspirators, once so certain of their cause, found themselves branded as parricides—murderers of Rome’s father.

Antistius' forensic assessment, while overshadowed by the grand sweep of history, remains a remarkable detail of the Ides of March. In his examination of Caesar’s lifeless body, he saw not just the marks of violence and betrayal, but a final, fatal wound—the wound that ended the Republic and set Rome on the path to Empire. (Antistius Medicus and the ides of March, by Ann Ellis Hanson, in the book "Medicine and markets in the Graeco-Roman World and Beyond")

William Shakespeare, about 150 years later, cemented the "Ides of March" into the cultural lexicon with his play "Julius Caesar," specifically through the phrase "Beware the Ides of March." This phrase has since come to symbolize forewarnings of treachery and calamity, encapsulating the notion, of an ominous harbinger.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: