Cato the Elder and the Roman Spirit: Discipline, Duty, and the Fall of Carthage

Cato the Elder is a fascinating figure in Roman history, embodying the traditional Roman virtues of discipline, frugality, and loyalty to the Republic.

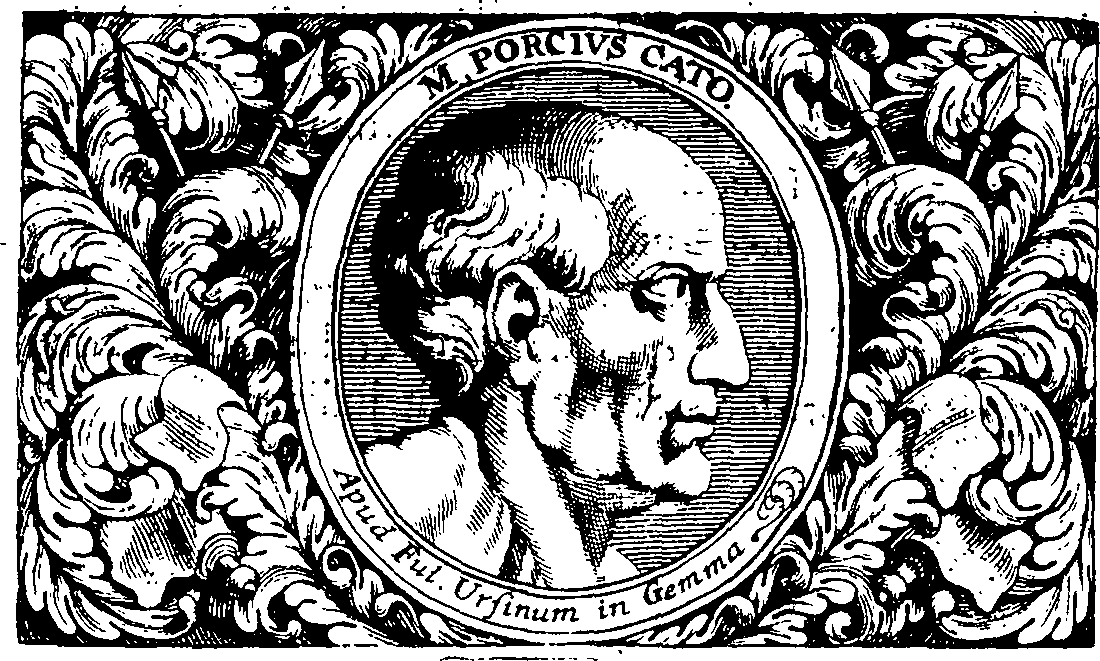

Born in 234 BCE, Cato was known as Cato the Censor for his strict morality and conservative values, which he tried to impose on Roman society, particularly during his time as censor in 184 BCE. He also earned the nickname Cato the Wise or Cato Major to distinguish him from his great-grandson, Cato the Younger.

Cato the Censor stands out as one of the earliest figures in Roman history for whom we have substantial biographical details. Our sources provide a rich portrayal of his life and character, capturing not only his public and political deeds but also his personal habits, sayings, and various anecdotes.

Much of this information comes from Cato's own literary works. As the first free-born Roman to write literature in Latin, Cato produced an extensive body of prose and highlighted himself prominently in these works, using the medium in a remarkably original way.

Old and New Views of Cato

The reputation of Cato the Elder has long been shaped by caricature, both by ancient writers and modern scholars. Cicero, less than a century after Cato’s death, portrayed him as a strict yet affable figure, distinct from his descendant, Cato the Younger.

In his writings, Cicero suggests that the Elder Cato, while severe, balanced his gravitas with kindness and adaptability, qualities he found lacking in the later "Cato model" adopted by his descendant. Cicero’s portrayal, however, may have been influenced by his rhetorical objectives, creating a slightly idealized version of Cato that emphasizes moral rectitude and consistency.

In modern scholarship, Cato is often depicted as a staunch traditionalist, fiercely anti-Greek, and morally rigid. This image stems in part from Cicero’s and other Roman authors' views of him as a symbol of conservative values, resistance to Greek influence, and devotion to Roman customs. This view persisted in educational texts and influenced early impressions of Roman history, where Cato appears as a narrow-minded reactionary whose principles often verge on inflexibility.

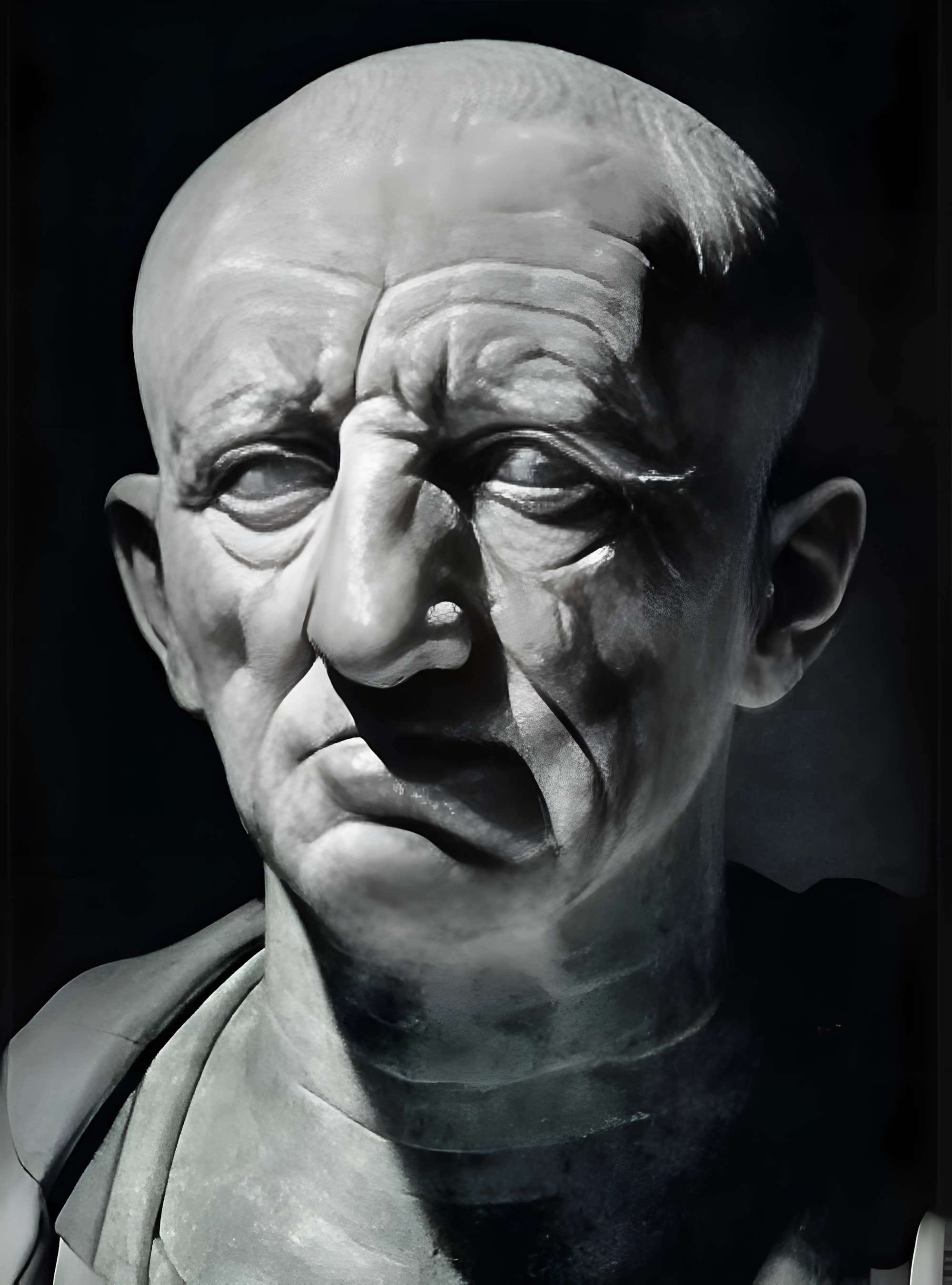

Yet, ancient sources, such as Nepos, give a more complex picture, describing Cato as a "master of all good skills" with remarkable versatility. He was seen as a farmer, orator, general, legal expert, and lover of literature—qualities that later Romans, including Plutarch, associated with a "Renaissance man."

Plutarch’s Life of Cato continues to shape interpretations of Cato's character, portraying him as fiercely committed to his values but sometimes at odds with his ideals of simplicity and frugality. Plutarch describes Cato as both a reformer and a harsh critic of the times, a man unyielding in his convictions yet occasionally hypocritical in his personal dealings.

He accuses Cato of an extreme dislike for Greek philosophy, and Plutarch's portrayal has led some to view Cato as reactionary and anti-Hellenic.

A possible representation of Cato the Elder looking at a bust of Sofocles in disdain. Illustration: Midjourney

Despite these conflicting images, ancient writers generally praised Cato’s commitment to moral and civic duty, even as his severity and moral crusades drew criticism. Cato’s reputation for unwavering virtue and eloquence persisted, marking him as a complex figure whose values defined his public life and set a standard for Roman ideals.

Through the centuries, the multifaceted portrayal of Cato—from the staunch traditionalist to the intellectual reformer—continues to invite debate on his legacy in Roman culture and history. (The elder Cato: A philological reassessment, by Churchill, James Bradford. University of Illinois)

Cato the Censor and the Origins of Latin Prose: From Poetic Translation to Elite Writing

Enrica Sciarrino’s "Cato the Censor and the Beginnings of Latin Prose: From Poetic Translation to Elite Transcription" explores how Cato the Elder shaped the early Latin prose genre in the context of societal hierarchies and power dynamics. Sciarrino argues that Cato’s work was more than literary; it was a strategic vehicle for asserting authority and redefining Roman values against the “alien” influence of Greek culture.

Sciarrino suggests that in early second-century BCE Rome, writing prose in Latin was a significant social act, particularly in contrast to Latin poetry, often composed by immigrant professionals and deeply rooted in Greek influence. Cato, born in Tusculum and a self-made figure (homo novus), used his prose to project traditional Roman virtues and to distinguish his legacy from the Greek-inspired poetry of his contemporaries.

Sciarrino posits that Cato’s writings were “transcriptions”—texts presenting themselves as codified forms of Roman speech and ritual, thereby reinforcing his authority and legitimacy. Cato’s opposition to Greek culture is highlighted in a fragment of his Ad Filium, in which he warns his son about Greek literature and doctors, whom he depicts as a cultural and physical threat to Romans.

He claims, “Whenever this race will give its literature, it will corrupt everything…if they will send their doctors here.” Cato’s view positioned Greek literature as “alien and alienable,” something that could disrupt the values and stability of Rome.

In her study, Sciarrino asserts that Cato used prose not simply to convey ideas but as a tool of cultural power, a way to assert his authority and set himself apart from the Greek-inspired poetry that had become prevalent in Rome. She emphasizes that the choice of literary form was a statement of identity, with Cato’s prose standing in opposition to poetry, which was rooted in Greek traditions and often performed rather than read.

Sciarrino explores the distinction between poetic and prose authorship by comparing Cato with Ennius, an earlier Roman poet who embraced a “three-hearted” (tria corda) identity, symbolizing his connection to Greek, Latin, and Oscan cultures.

Ennius, Sciarrino explains, relied heavily on “the intake of Greekness” in his work, while Cato defined himself against Greek influence, rejecting it as “alien and alienable.” Where Ennius’ identity was a blend of cultures, Cato positioned his writing as a purely Roman voice, untouched by foreign styles, which he believed would undermine the values of Rome.

Through her analysis, Sciarrino describes Cato’s prose as operating in a unique space distinct from Greek-influenced poetry, creating what she calls “transcriptions” of Roman social practices. These texts presented themselves not as works needing to be performed, but as codified expressions of Roman speech and ritual. By doing this, Cato avoided the dependency on audience reception that could limit the social influence of poets like Ennius, who performed for approval.

This gave Cato greater control over his public image and allowed him to use his prose as a powerful form of self-representation.

A possible representation of Cato the Elder, as he is reading his works. Illustration: Midjourney

Ultimately, Sciarrino concludes that early Latin literature reflects diverse subjectivities and social dynamics, shaped by the identities of their authors. For Cato, writing was a medium for asserting a distinctively Roman cultural identity, providing him a platform to project values resilient to foreign influence. Through his texts, Cato not only built his own legacy but also laid foundational ideas of Roman virtue, loyalty, and authority that would continue to influence Roman thought for generations.

The Origines of Cato

Enrica Sciarrino's study, Putting Cato the Censor’s "Origines" in its place, examines the fragmented state of Cato’s Origines—considered by scholars to be the first Latin historical prose—and the unique challenges this text presents. With its incomplete preservation, the work's form and content are known only through scattered references from later authors, particularly Cornelius Nepos.

Nepos provides a valuable, albeit limited, outline of Origines, explaining that the seven-book work spans Rome’s early history, the origins of various Italian states, and several significant wars. Notably, Nepos points out that Cato avoids naming military leaders, emphasizing instead the events and geographical features of Italy and Spain. Sciarrino notes this omission as likely a deliberate strategy by Cato, an effort to resist the aristocratic practice of associating history with elite individuals—a stance aligned with his status as a homo novus (new man in Roman politics).

“When he was an old man he began to write "histories."

There are seven books of these. The first contains the deeds of the kings of the Roman people, the second and the third the origin of each Italian state; on this account, he seems to have called the whole work Origines. In the fourth, however, is the First Punic War, in the fifth the Second.

And all of these matters are told in a summary fashion; as for the remaining wars, he continued in the same way down to the praetorship of Servius Galba, who plundered the Lusitanians.

And he did not name the leaders of these wars but recorded the events without names.

In the same books he accounted for the noteworthy events and sights of Italy and the Spanish regions; in these there is evident much industry and diligence but no learning.”

Nepo, Life of Cato

Cato’s omission of personal names and his surprising inclusion of Greek cultural references may reflect deeper intentions. The avoidance of naming leaders seems to signify Cato’s resistance to celebrating individual power, while the Greek influences, despite Cato's anti-Greek reputation, reveal a complex engagement with cultural materials that adds nuance to his persona.

Viewing Origines solely as a historical text misses a significant dimension. Understanding it within a "performative" lens, feels better, where the work is seen as a medium for Cato’s active engagement in the socio-political debates of his time. By approaching Origines as a text embedded within the public discourse on elite identity, Sciarrino recontextualizes Cato's work as an intervention in the changing Roman landscape, where Rome was transitioning from a city-state to an empire.

The study proposes that Origines was not just historical prose but an active response to Rome’s evolving identity, suggesting that the text operated as a form of public performance, aiming to redefine traditional boundaries of prose and poetry. Sciarrino’s exploration illuminates Origines not merely as an artifact but as a tool through which Cato sought to influence and shape Roman society, placing it back into its "proper context" as a culturally and politically resonant text, operating at the crossroads of literature, performance, and social commentary.

Carthage Must Be Destroyed: Cato the Elder's Fierce Crusade Against Rome’s Rival

“The last of his political actions is supposed to have been the destruction of Carthage; while the younger Scipio brought about the fulfilment of the act, it was by the design and especially the judgment (gnome) of Cato that the Romans undertook the war.”

Plutarch, Life of Cato the Elder

Cato the Elder could almost be said to have written a manual titled How to Do Things with Words, given the impact of his famous dictum on Carthage. This statement, often seen as his most memorable and influential phrase, arguably carries even more weight in historical memory than veni, vidi, vici. What makes Cato’s statement so powerful is the way it moves beyond merely describing past actions—it actively shapes a future in which these actions feel unavoidable.

Accounts of Cato tend to support this portrayal by merging his statement with its ultimate outcome, glossing over the Senate’s initial response to the Carthage debate, which was to propose relocating rather than destroying the city. Numerous texts seem to blur the distinction between word and action. A prime example comes from Pliny the Elder, who succinctly records:

"[W]hen he was declaiming in every meeting of Senate that Carthage must be destroyed [Carthaginem delendam] ... and at once they embarked on the third Punic war, in which Carthage was destroyed [Carthago deleta est]

Cato’s famous statement, "Carthage must be destroyed," goes beyond a call for action—it casts Carthage’s destruction as an inevitable outcome. This sense of inevitability is reinforced by ancient writers like Pliny, who captures Cato’s demand, Carthago delenda est, as fulfilled in Carthago deleta est, leaving later generations to marvel at how Cato’s words translated into reality.

For us, and for ancient historians like Plutarch and Pliny, the destruction of Carthage seems a fixed event, leading us to project this necessity back onto Cato’s time, as though he were a voice not of his own era but of the future, embodying a fate already written. This retrospective view amplifies Cato's significance, making him seem almost prophetic.

In this light, Cato is less a figure of his own time and more a symbol of the future—a figure whose powerful words are understood only in hindsight, once Carthage has indeed been destroyed. Carthage itself occupies an unusual, almost "undead" position in these narratives: it "exists" in Cato's statement as a target of impending destruction and in the perfect tense as something already conquered. The reality of Carthage in these accounts hovers between an anticipated future and a completed past.

This perspective makes Cato's campaign against Carthage appear distinct from the destruction of another great city in 146 BCE: Corinth. While Corinth’s destruction was seen as a lesson to the Greeks, Carthage’s fall resonated as the elimination of a formidable rival, and the Romans’ identification with Carthage added to the gravity of the event.

Scipio Africanus the Younger, at Carthage’s fall, famously expressed fear for Rome’s own future—a sentiment reflecting the Romans’ awareness of Carthage as both a rival and a mirror. Carthage thus became a focal point for Rome’s anxieties about its own mortality and the irreducibility of certain threats within its empire. This deeper resonance is evident even in Lucretius, who recalls the Punic wars to evoke humanity’s fear of nonexistence, using Carthage as a metaphor for ultimate annihilation.

“Therefore death is nothing to us and matters not one bit, since the nature of the mind is considered to be mortal.

And just as we felt no distress with regard to past time, when the Carthaginians were coming to battle from all sides, when everything was shaken by the terrifying tumult of war, and, shivering, trembled under the high vaults of the heavens, and was in doubt under whose domination all humankind on land and sea must eventually fall; so, when we are no more [ubi non erimus], when body and soul, from which we are made one, are split, then surely nothing can affect us, who are no more [qui non erimus], nor can anything cause us sensation, even if the earth mingles with the sea and the sea with the sky.”

Carthage holds an ideal position both in space and time as a symbol within the Roman imagination. It stands at the center of Rome’s imperial ambition precisely because it remains unconquerable in spirit. Preceding Rome as its ultimate foe, Carthage endures as an ever-present memory; its destruction does not diminish Rome’s desire for that destruction.

Pliny’s progression from delenda (the desire for destruction) to deleta (the aftermath of fulfillment) illustrates that the Romans found the actual conquest less compelling than the lingering desire itself. What endures—the “undead city” or Carthage as a symbol—becomes a leftover or surplus-enjoyment. This haunting symbol, essential to framing the Roman world, resists complete assimilation and emerges as a product of Rome’s very act of symbolization.

Cato’s Famous Figs in the Roman Senate

Carthage’s abundance of war materials emphasizes it as a military threat, but Cato seems particularly affected by the idea that Carthage takes a certain dangerous pleasure in its own wealth. This view of Carthage as a place of indulgence influences Cato's choice of a vivid example to persuade the Romans of the need to destroy their rival. In a symbolic act as memorable as his words, he presents figs from Carthage before the Roman Senate:

“Besides this, they say, Cato purposely dropped some Libyan figs in the Senate as he threw his toga over his shoulder, then when the senators wondered at their great size and beauty, he said that the land which had borne these was only three days' sail from Rome.

But the next thing he did was more violent, namely, his practice when declaring his opinion on any subject at any time of saying in addition this: "And it seems to me that Carthage should not exist."

Plutarch, Life of Cato the Elder

The figs primarily serve to illustrate Carthage's unsettling closeness to Rome, acting as a synecdoche. However, their immediate impact is to represent the city's lush prosperity, functioning metaphorically. Just as Carthage has flourished, the figs' impressive size and beauty evoke admiration, wonder, and perhaps even pleasure among the senators. This imagery extends Cato's famous statement, implying that Carthage’s very existence—and the indulgent pleasures it symbolizes—is itself intolerable.

The selection of figs may further underscore the idea of Carthage embodying excessive pleasure, as figs were symbolically linked to the female breast among ancient Romans. The ficus Ruminalis, where Romulus and Remus were famously suckled, exemplifies this association. Cato's use of a fig to represent Carthage’s remarkable prosperity evokes similar associations, especially as he dramatically reveals the figs by shaking them from his toga.

It’s essential to note that, regardless of what the fig may symbolize for the Carthaginians, for Cato, it is not merely food. Instead, it represents a form of enjoyment that Cato himself seemingly cannot partake in—a pleasure that appears central to his hostility toward Carthage.

The phrase Delenda est Carthago may represent history’s earliest recorded incitement to genocide.

A possible representation of the genocide of Carthage by Roman soldiers. Illustration: Midjourney

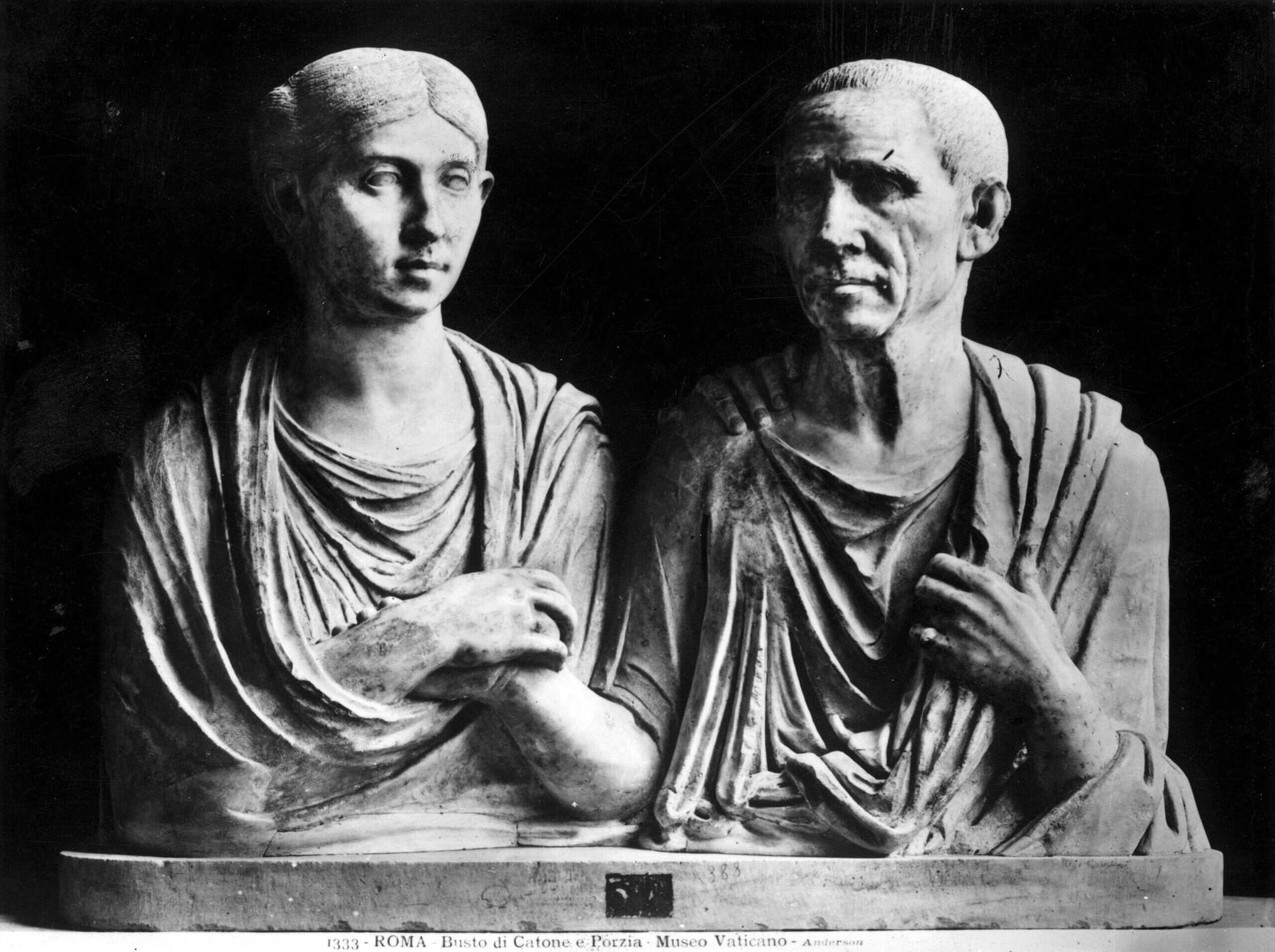

These were the words of Marcus Porcius Cato, the Censor. According to Plutarch, Cato concluded every Senate speech with this call, “regardless of the topic,” from 153 BC until his death in 149 at age 85.

His opponent, Scipio Nasica—son-in-law of Scipio Africanus, who defeated Hannibal in the Second Punic War (218–202 BC)—would counter with, “Carthage should be allowed to exist.” Yet dissenters like Scipio were eventually silenced. Rome had resolved to go to war "long before" it officially commenced the Third Punic War, just before Cato's passing. One of Cato’s final Senate speeches, delivered before a Carthaginian delegation in 149, proved pivotal.

“Who are the ones who have often violated the treaty?… Who are the ones who have waged war most cruelly?… Who are the ones who have ravaged Italy?

The Carthaginians.

Who are the ones who demand forgiveness?

The Carthaginians.

See then how it would suit them to get what they want.”

The Carthaginian delegates were denied a chance to respond, and Rome soon began a three-year siege against the wealthiest city of the ancient world. Out of a population of 200,000–400,000, approximately 150,000 Carthaginians died. Appian mentions a single battle where "70,000, including non-combatants," were killed, though likely an exaggeration.

Polybius, who witnessed the campaign, confirmed the "incredible number of deaths" and described the Carthaginians as "utterly exterminated." In 146 BCE, Roman forces under Scipio Aemilianus—an ally of Cato and son-in-law of Cato’s son—demolished Carthage, enslaving 55,000 survivors, including 25,000 women. Plutarch attributed the city's destruction mainly to "the advice and counsel of Cato."

This was not a war of indiscriminate slaughter; the Romans spared many survivors, including adult males. In 149 BCE, Carthage had already complied with Rome’s demand to surrender 200,000 weapons and 2,000 catapults, unaware that the Senate had secretly decided "to destroy Carthage for good" once the war ended.

The Senate's sudden new demand for the Carthaginians to abandon their city and its religious sanctuaries provoked resistance that Rome met with "the destruction of the nation." Rome’s policy of "extreme violence," which resulted in the “annihilation of Carthage and most of its inhabitants,” aligns with the modern legal definition of genocide per the 1948 United Nations Genocide Convention: the deliberate eradication "in whole or in part" of a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.

How much did Cato the Elder influence the Destruction of Carthage?

Although it would be anachronistic to judge Rome’s actions by 20th-century laws, it’s equally important to acknowledge the opposition within Rome to Cato's approach. What ideology drove the demand for a disarmed commercial city's complete eradication? Beyond any strategic motivations for the 149 BCE siege, Cato’s fervor in pushing for Carthage's destruction stands out.

His accounts of Punic "atrocities" likely stirred memories among Romans of Hannibal’s devastation of Italy. Cato’s alleged list of Carthaginian treaty violations, though lacking solid historical basis, emphasized legalistic points that other writers didn’t prioritize. Cato's rationale shares striking parallels with more recent instances of genocide. Cato was fixated on militaristic expansion, idealized agrarian values, and reinforced hierarchies of gender and social order, while harboring cultural and racial biases.

The decision to destroy Carthage was an unusual one in Rome’s history of frequent warfare; it was premeditated and carried out even after Carthage had surrendered. While ancient sources differ on whether Carthage truly posed a major threat or if Rome’s demands were motivated by “extreme power hunger,” Cato saw the danger as partly internal, believing Carthage’s prosperity and proximity could tempt Roman complacency and luxury.

Cato, a distinguished Roman orator and administrator with a reputation for bluntness and dedication, had long warned of the dangers of wealth and extravagance, especially after criticizing the indulgences of Scipio Africanus, a hero of the Second Punic War. In his writings, Cato omitted the names of Roman leaders, possibly to caution against the lure of fame, while highlighting Hannibal’s symbolic elephant. For him, the Carthaginians were “already our enemies” due to their capacity for war, regardless of formal conflict.

In 195 BCE, during his consulship, Cato led a brutal campaign in Spain to suppress revolts in former Carthaginian territories, known for his harsh tactics against rebels and his claim of capturing over 400 cities. His control over Spain was so enduring that even subsequent uprisings were ruthlessly quashed.

By 152 BCE, at age 81, Cato visited Carthage and was alarmed by the city’s recovery. Now a prosperous commercial hub, Carthage was “brimming with wealth and weapons,” and upon his return to Rome, he famously displayed (as already mentioned above) the Libyan figs to the Senate, warning them of Carthage’s proximity, only three days’ sail from Rome. For Cato, this vibrant, nearby threat had to be destroyed for Rome’s safety.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: