Pliny the Elder: The Author of the World’s First Encyclopaedia was Roman

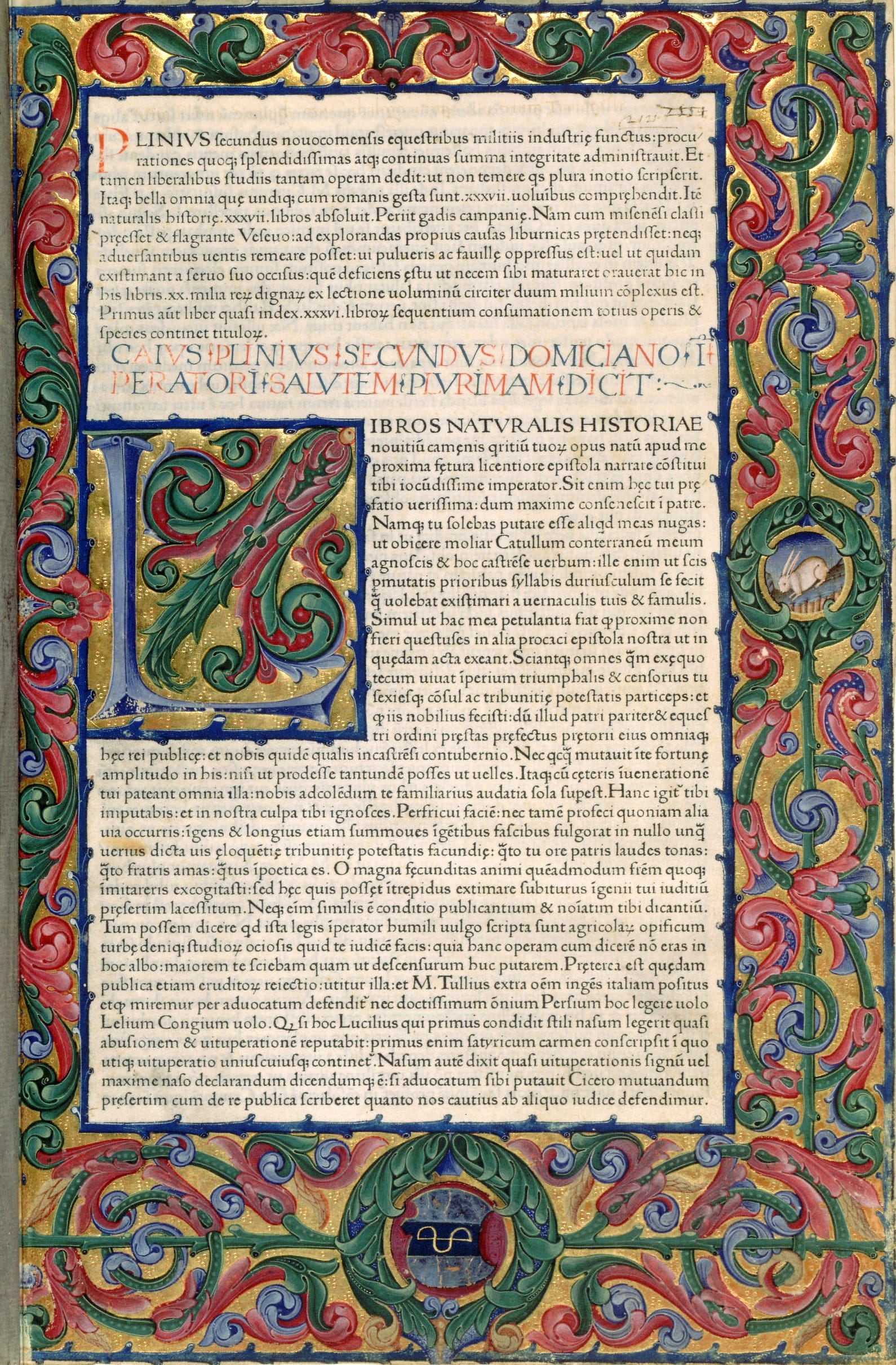

Naturalis Historia by Pliny the Elder is the world's first encyclopaedia.

Pliny the Elder, a Roman author, natural philosopher, and naval commander, left a lasting legacy with his comprehensive work, "Naturalis Historia". This encyclopaedia, completed in 77 CE, is considered one of the largest single works to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, and it profoundly influenced both the Renaissance and modern science.

In the introduction to his monumental work, "Natural History", addressed to Titus, who ascended to the role of emperor shortly before Pliny's demise in the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius on August 24, 79, Pliny articulates his objective as exploring “the nature of things, that is, life.” His extensive research compiles insights from over four hundred sources, covering a broad spectrum of topics including animals, plants, minerals, metals, botany, medicine, geography, literature, and the arts.

Who was Pliny the Elder?

Gaius Plinius Secundus, the man we know as Pliny the Elder, was born either at the end of AD 23 or the beginning of AD 24 in Novum Comum, a town in what was then the Roman province of Transpadane Gaul, now known as Como, Italy, located near the Swiss border.

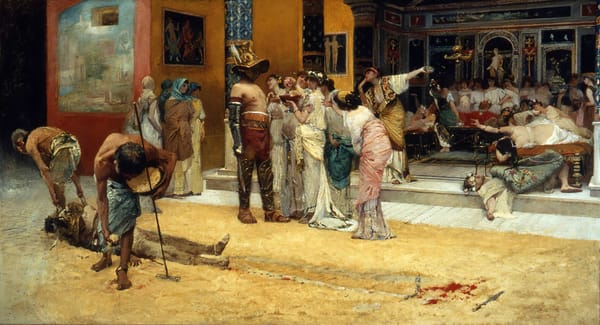

He was born into the equestrian class, a wealthy tier of the Roman Empire's aristocracy, which is often translated as "knights" in English. This class formed the municipal governing body of the Empire, and its members were expected to perform military service. The equestrians were relied upon to exhibit heroic behavior, demonstrating to the lower classes that they deserved their elevated social status.

“The fortunate man, in my opinion, is he to whom the gods have granted the power either to do something which is worth recording or to write what is worth reading, and most fortunate of all is the man who can do both. Such a man was my uncle…”

Pliny the Younger, Letter 6.16

At the age of 24, Pliny began his military service in Germany. Over the course of approximately ten years, he completed three tours as a cavalry commander. During this time, Pliny gained a reputation for his outstanding performance and leadership skills in the army.

While serving in the army, Pliny developed a keen interest in literature and grammar, which led him to start writing. His first work was titled "De jaculatione equestri", focusing on the use of javelins by cavalry. He later authored a comprehensive 20-volume series called "Wars in Germany", detailing military campaigns in the region.

Around AD 59, at the age of 36, Pliny relocated to Rome during the reign of the notorious Emperor Nero, who had been in power for five years, and began his career as a lawyer.

To avoid attracting unwanted attention, Pliny maintained a low profile, later characterizing Nero as "an enemy of the human race". He worked in Rome and, to further distance himself from Nero’s dangerous rule, possibly resumed his military duties until Nero's death in AD 68.

Upon Vespasian's ascension to emperor in AD 69, Pliny the Elder, a former military comrade, became one of his most trusted advisors. Pliny held the position of governor in several of Rome's imperial provinces, which likely included roles in regions such as southern France, northern Africa, Spain, and Belgium. Additionally, he spent periods in Rome where he provided counsel to Vespasian and his son, Titus, who shared the responsibilities of the emperor with his father. He earned a reputation for his upright character and his final role was as the commander of the naval base at Misenum, located on the Bay of Naples—a significant military appointment that he approached with utmost dedication.

Creation of "Natural History"

Pliny's "Natural History" is an extensive collection of knowledge that covers a vast array of subjects including astronomy, anthropology, geography, botany, horticulture, farming, zoology, medicine, chemistry, minerology, and art.

Comprising 37 volumes, the work was an attempt to document all human knowledge of the natural world in Pliny's time. Drawing from over 400 sources, including his own observations and the work of predecessors, Pliny aimed to provide a critical and comprehensive resource for the Roman public.

Pliny's "Natural History" may be considered the first Western encyclopedia but defining it as such requires understanding that the concept of an encyclopedia has evolved significantly.

While modern readers might recognize it as an encyclopedia, this would not necessarily align with the expectations or recognition of its earliest audiences. The work itself has had a considerable influence on how we interpret and engage with historical texts.

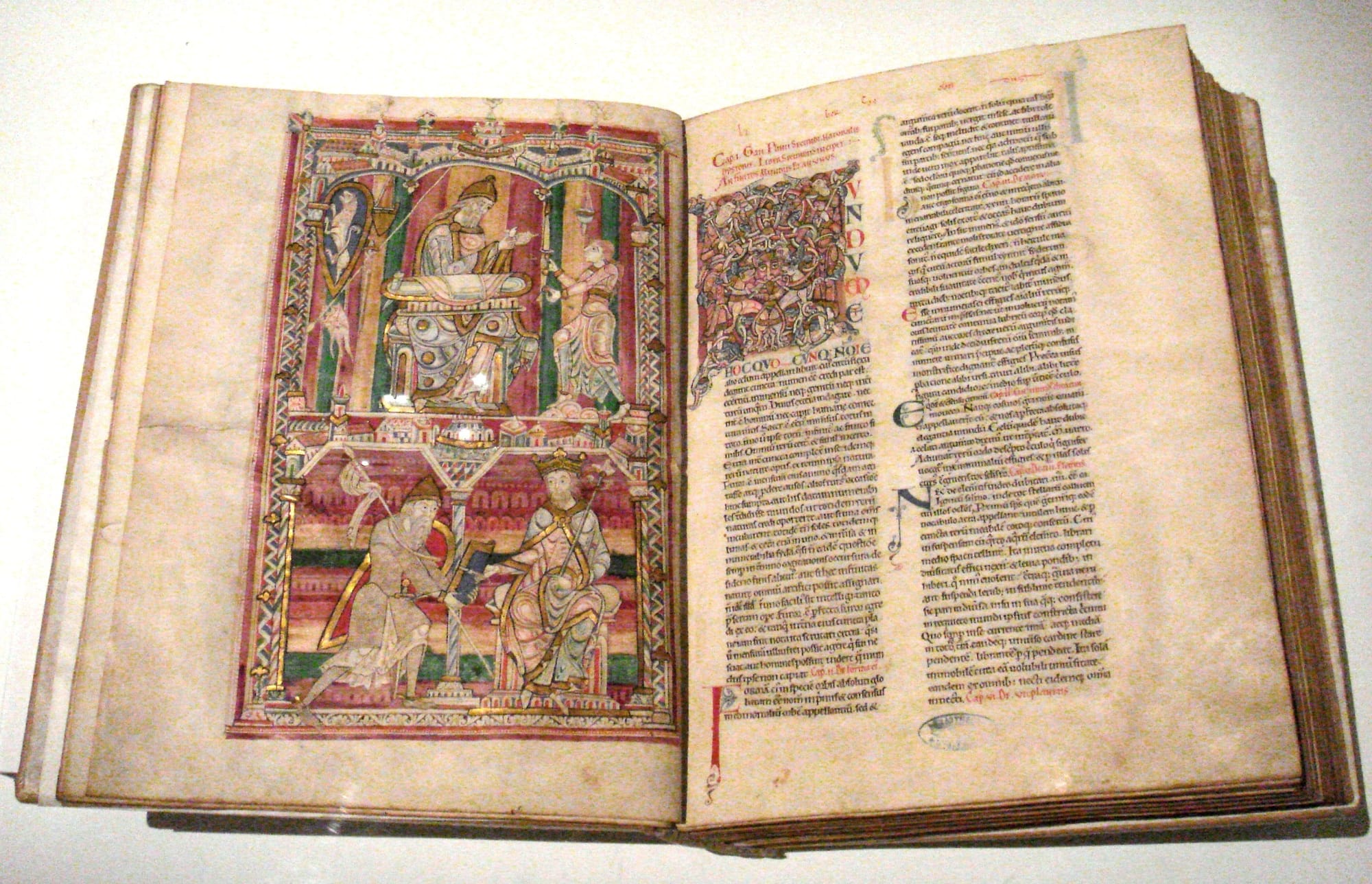

Over centuries, it has been a critical reference in various fields, from medicine to zoology, informing scholars and serving as a cornerstone for the development of numerous disciplines. Although its direct utility for contemporary practitioners may have diminished, its value to antiquarians and classicists remains substantial, providing a window into ancient knowledge and practices. The enduring scholarly reliance on Pliny's work illustrates the complex ways in which historical texts continue to shape modern academic disciplines, even as the nature of these texts and their interpretations evolve over time.

Pliny the Elder's "Natural History" begins with a dedication to Emperor Titus, offering a preview of the extensive contents within the 37-book series. The initial volume delves into cosmology, touching upon the universe, celestial bodies, and fundamental elements. It is followed by a detailed geographic exploration of the Earth and its varied inhabitants. The subsequent book shifts focus to humanity and technological advancements.

“…written for the masses, for the farmers and workers, and to interest people in their leisure time.”

Pliny the Elder

The compendium then examines animals both terrestrial and aquatic, with separate discussions dedicated to birds and insects. Most of the volumes center on botany, discussing trees, plants, flowers, and fruits, extending into their agricultural practices and medicinal uses. Pliny also explores other medicinal resources derived from animals. The final sections are devoted to minerals and metals, including their applications in painting and the arts, culminating in one of the earliest comprehensive accounts of art history.

In the second book of "Natural History", Pliny the Elder embraces the traditional Greek astronomical theories, acknowledging the Earth's spherical shape and its implications on phenomena like day and night cycles, sunrises, and sunsets.

He identifies the planets known during the classical era: "Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, the sun, Venus, Mercury, and the moon." Pliny's descriptions, particularly of the sun and moon, are imbued with a mythological perspective, often personifying these celestial bodies in line with Roman and Greek traditions. He describes the sun with profound reverence: "[the Sun] lends his light … to the rest of the stars, is splendid, supreme and sees and hears everything."

Pliny wants his readers to know that his book is well researched, covers a wide range of topics, and is up to date. He writes:

“I have included in 36 books 20,000 topics… acquired by the study of about 2,000 volumes… gathered by the careful examination of 100 select authors; and to these I have made considerable additions of things, which were either not known to my predecessors, or which have been lately discovered.”

Pliny The Elder

Modern scholars put the number of pieces of information at 37,000.

Pliny the Elder authored his expansive work "Naturalis Historia" not for profit but as a scholarly endeavor. In his era, long before the advent of the printing press, each book had to be manually transcribed by scribes, making the production of books labor-intensive and costly. Although Pliny might have commissioned a few initial copies with possible financial backing from the emperor, subsequent copies were made by those who hired scribes to painstakingly replicate the text, which contains over a million words.

Drawing from the works of hundreds of esteemed authors across various scientific disciplines, Pliny meticulously gathered thousands of details, aiming to preserve ancient sciences for future generations. As noted by the late classicist David Eichholz, Pliny was driven by "his anxiety to save the science of past ages from the forgetful indifference of the present."

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: