Pompeii’s Taverns and Wine Bars: The Hospitality Business of an Ancient City

Behind Pompeii’s grand villas thrived a bustling world of taverns, inns, and bars. From graffiti complaints about watered wine to marble-clad counters that lured passersby, these establishments reveal the everyday rhythms of food, drink, and company in the Roman world.

In the shadow of Pompeii’s grand banquets and imperial feasts thrived a very different world of eating and drinking. Along busy streets and in smoky alleys, counters simmered with hot stews, jars brimmed with cheap wine, and dice rattled across worn wooden tables.

These were the cauponae, popinae, tabernae, and thermopolia—the beating heart of Rome’s “fast food” culture. Far from the marble dining halls of senators, they catered to workers, travelers, and slaves, offering quick meals, rough company, and sometimes more than food. To step into one was to glimpse the everyday Pompeii rarely shown in marble or verse.

The Problem of Labels: What Did ‘Taberna’ Really Mean?

Modern scholarship has shown that labeling Pompeian remains with Latin terms is not as straightforward as once believed. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century archaeologists applied words like taberna, caupona, hospitium, stabulum, popina, and thermopolium to structures in Pompeii almost indiscriminately, creating categories that may not match ancient realities.

Ancient Authors on Roman Taverns (Tabernae)

Even the Latin authors themselves used taberna in shifting ways. Ulpian defined it broadly as “all buildings fit for habitation” (Digest 50.16.183), an almost meaningless generalization.

In funerary inscriptions, however, tabernae were distinguished from aedificia and habitationes, hinting at a more specific type of structure. Vitruvius recommended tabernae and stabula in country forecourts to store produce and animals, again pointing to a functional role rather than a fixed form.

“Those whose estates are near a town ought to have in the forecourt both tabernae and stabula, so that the produce may be stored under cover, and the cattle also may be kept safe in stalls.”

Vitruvius, De Architectura

Etymologists traced the word back to tabula (plank) or trabs (beam), recalling its origin as the poor man’s hut. Juvenal describes shutters chained in place at night, reinforcing the image of modest wooden frontages.

“Everywhere the public sings, the drunkard quarrels, and the crowd of brawlers goes on fighting till dawn. One man tires out the chained shutters of his tavern with blows.”

Juvenal, Satires

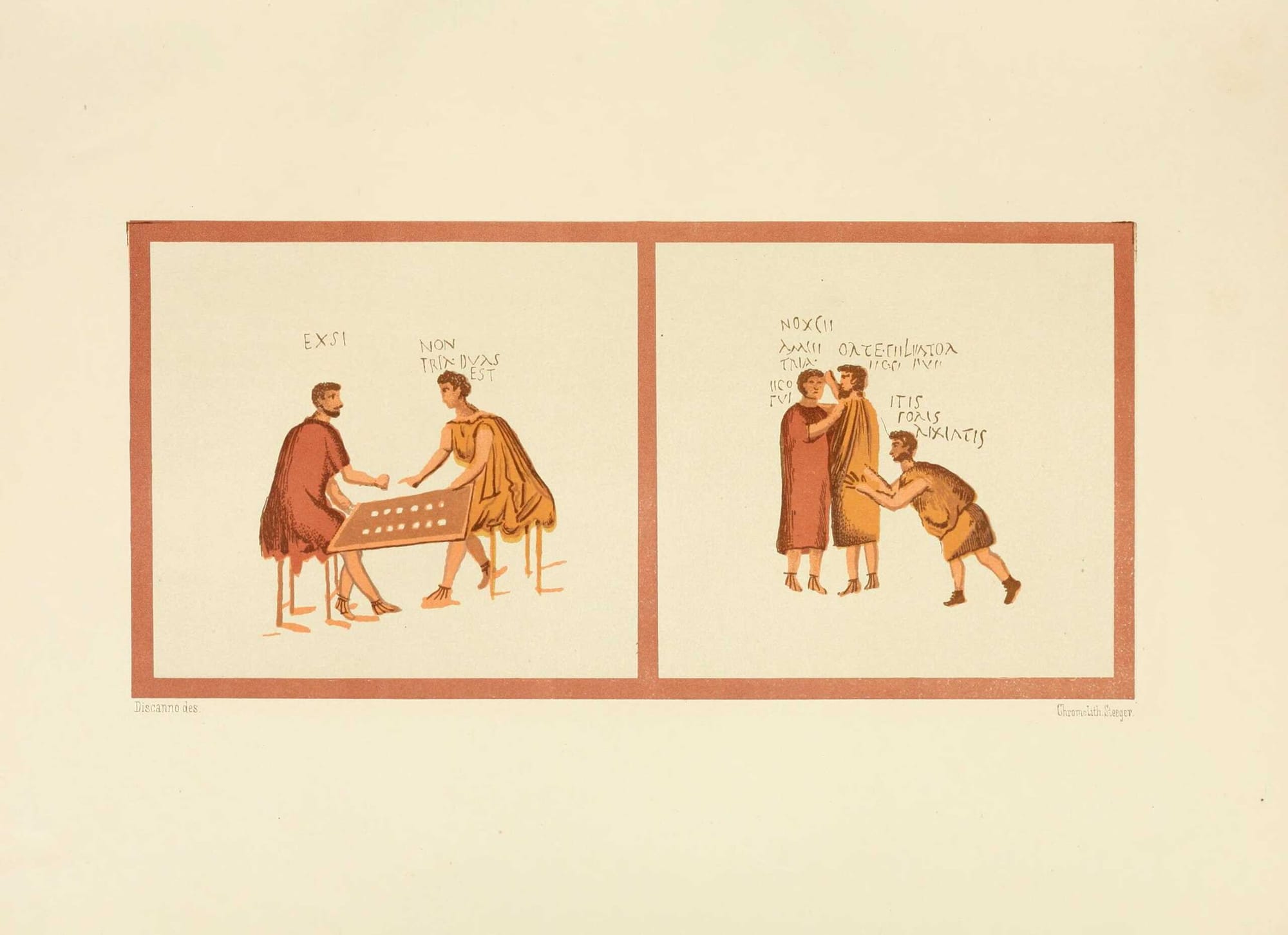

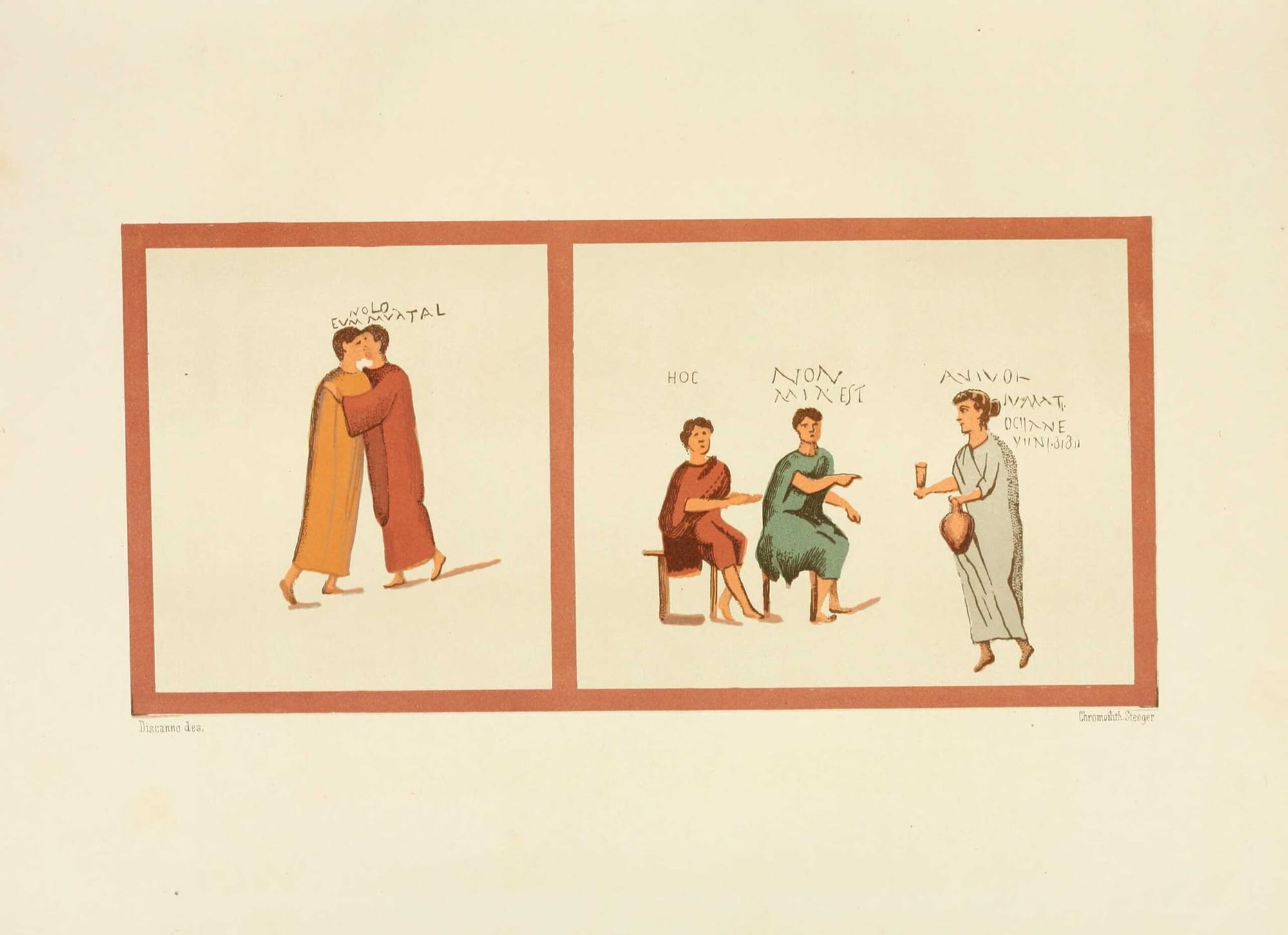

Reconstructed tavern scenes from Pompei (Caupona of Salvius), by Geremia Discanno. Public domain

Literary scenes suggest how tabernae worked in daily life. Martial praised Domitian’s edict compelling shopkeepers to keep within their thresholds, since their wares often spilled into the street.

“Now, thanks to your edict, Caesar, all the shops keep within their thresholds. Before, they had encroached upon the streets and porticoes, and their wares blocked the passers-by.”

Martial, Epigrams

Livy described the openness of Tusculum’s shops, doors wide and goods on display to passers-by.

“As he entered the city he found all the shops (tabernae) open, and saw that artisans were busy at their trades, while boys were being taken to school and teachers were in attendance; the whole city wore the aspect of peace.”

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita

The term was flexible. Some tabernae were little more than booths or stalls, others substantial two-storey shops.

“He brought me into a small shop (tabernula), humble though it was, yet with an upper story. There he lived with his wife, and there was even enough room to conceal both me and my ass.”

Apuleius, Metamorphoses

They might host moneylenders, doctors, barbers, bakers, butchers, and sellers of cheese, fish, or wine. While later tradition equates taberna with a tavern or wineshop, ancient evidence points to a multifunctional commercial space, often fronting the street with a wide doorway.

Modern analogy also colors interpretation. Roman tabernae resemble the street-front shops still seen in Naples or Rome, with broad openings inviting contact with customers. Yet, drawing too direct a line between ancient and modern shops risks anachronism. Function and use could shift, and the label taberna in antiquity was applied far more loosely than modern categories imply. (Finding commerce: the taberna and the identification ot Roman commercial space, by Claire Holleran)

Hospitia, Cauponae, Tabernae, and Popinae: The Four Faces of Roman Hospitality

In Pompeii and Herculaneum, as in many smaller Roman cities, eating and drinking establishments were part of daily life. Pompeii in particular preserves some of the best examples, where taverns, inns, and small restaurants dotted the insulae and clustered near the city gates.

These venues welcomed travelers but also served the city’s own lower classes, offering food, wine, companionship, and sometimes shelter. They were woven deeply into the fabric of Pompeii’s economy and society.

Roman hospitality businesses fell into four main categories: hospitia, stabula, tabernae, and popinae. A hospitium was originally a place that embodied the bond between host and guest, but in practice it came to mean an inn offering overnight accommodation, meals, and drink. Some were purpose-built, while others were converted from private homes.

The caupona was similar but generally more modest, catering to less affluent patrons. While some were comfortable, the word gradually acquired unsavory associations, and innkeepers eventually preferred not to use it. If the hospitium was akin to a hotel, the caupona might be compared to a roadside inn or bar with food and lodging.

Stabula were inns that also stabled animals. Recognizable by their broad sloping entrances that allowed carts to pass inside, they combined rooms for travelers with stalls for beasts of burden. These were especially common just outside or inside city gates, where space was often at a premium. Their layouts typically included an open courtyard ringed with kitchens, latrines, and sleeping quarters, with the stables at the rear.

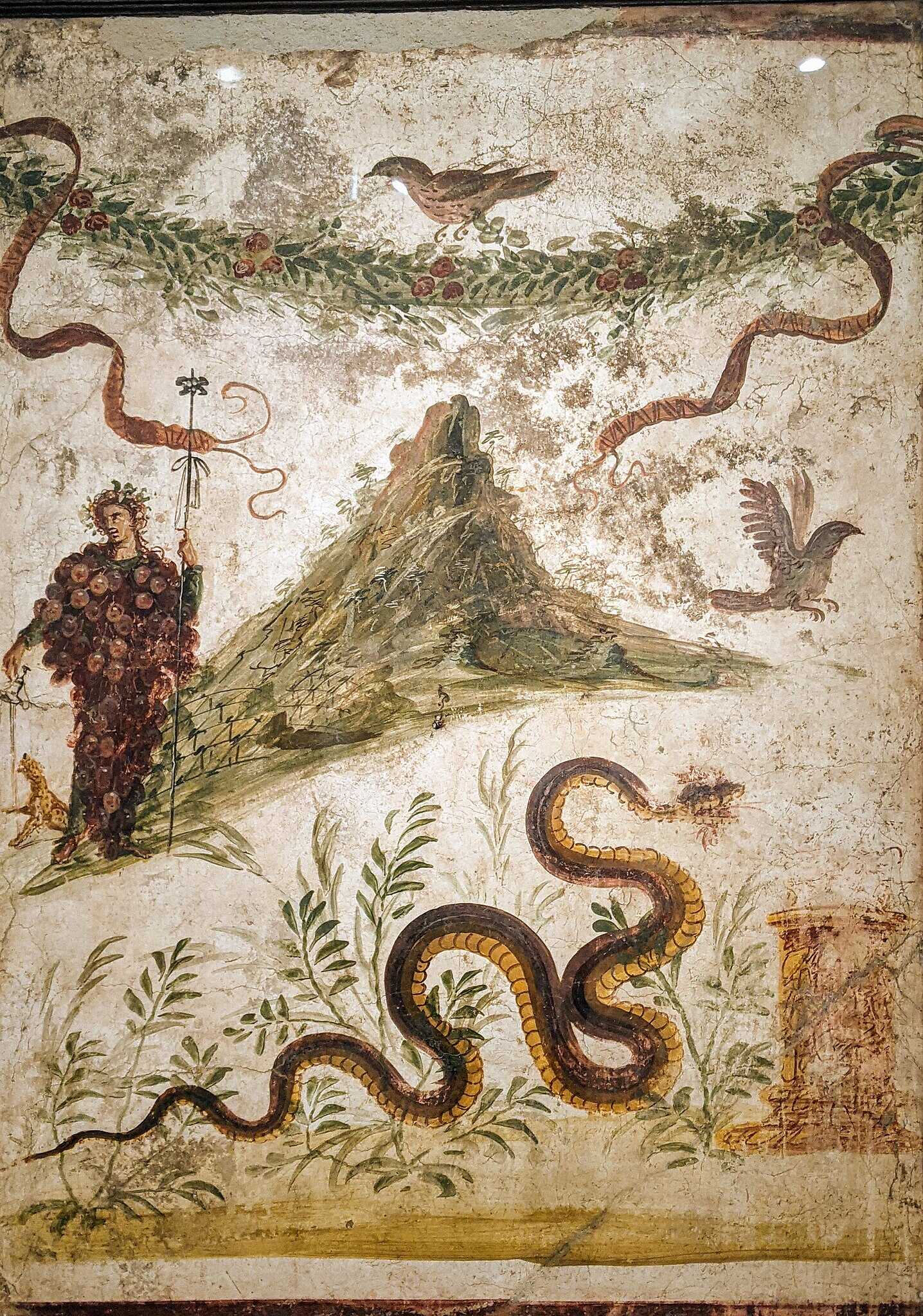

A series of frescoes from the Via dell’ Abbodanza (Abundance Street), in the Tavern of the Four Deities, depicting the Gods Apollo, Jupiter, Diana and Mercury. Credits: Sailko, CC BY-SA 4.0

The taberna began as a term for a shop, but by the first century CE it was often used for taverns. These establishments varied in size and quality. Sometimes they were combined with inns (caupona taberna), selling food and wine while providing rooms upstairs. The term could cause confusion, however, since many scholars use it to describe all kinds of shops.

Both tabernae and popinae served simple meals and drink, often from counters lined with sunken storage jars (dolia). The counters were usually L-shaped, with heating systems that allowed food and wine to be served warm. Some establishments, such as the Taberna of Fortunata in Pompeii, had multiple storage jars, stoves, niches, and even latrines tucked behind the counter. Others offered small eating areas either indoors or in adjoining gardens.

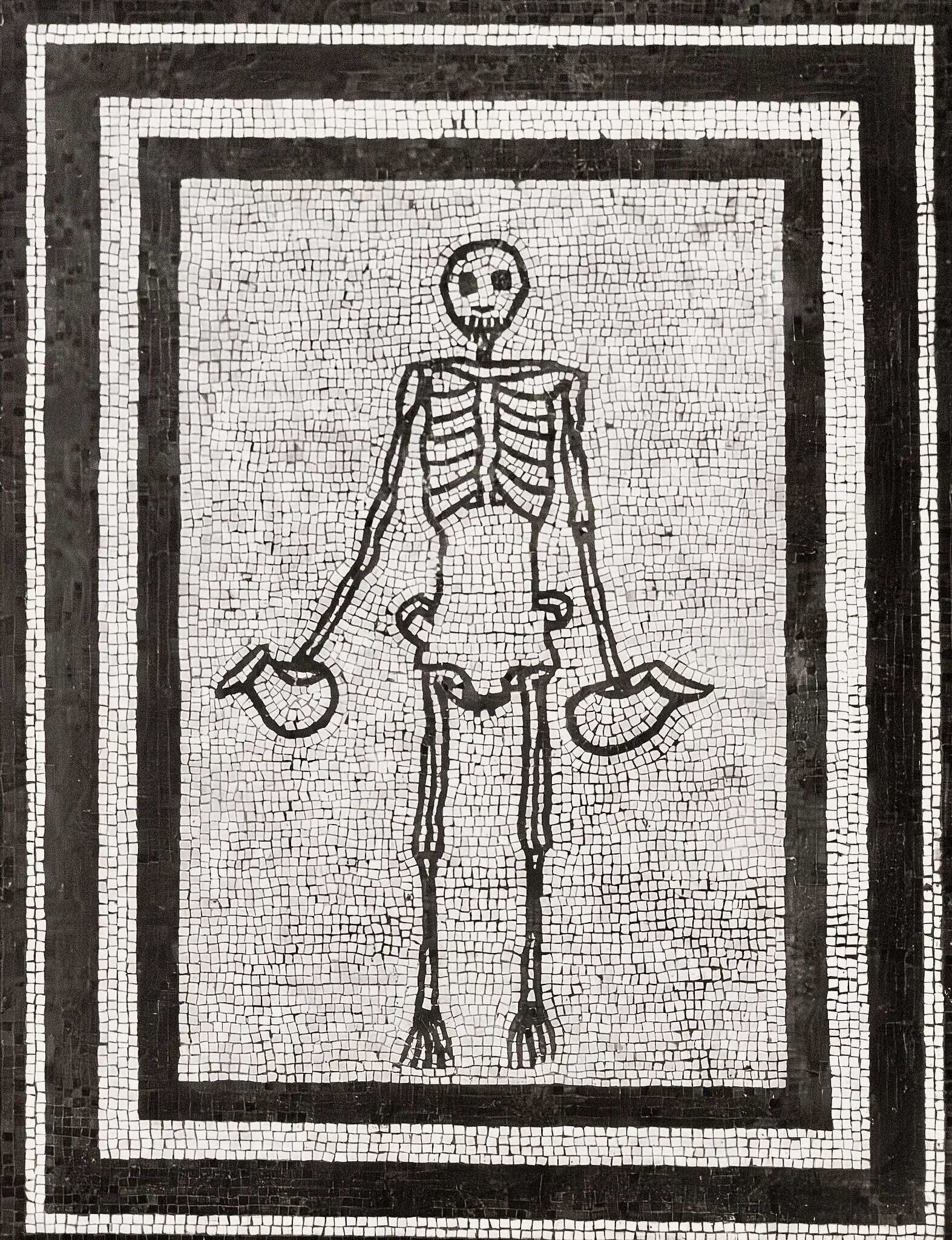

Popinae were the Roman equivalent of a casual sit-down restaurant, quick and affordable, but frowned upon by the elite. Upper-class Romans preferred to recline in triclinia and eat at leisure, so the bustle of the popina was considered coarse. Nevertheless, they provided an essential service to ordinary Pompeians.

In practice, the line between caupona and hospitium was blurry. Some inns offered gardens with triclinia, multiple bedrooms, kitchens, and even atria or reception rooms.

After the earthquake of 62 CE, many private houses seem to have been adapted for this purpose, their atria converted for storage or service. Inns at Pompeii reveal this blending of domestic and commercial space, where hospitality businesses were carved into the city’s very fabric.

At the Gates: Inns, Guests, and Graffiti in Pompeii

At Pompeii, many hospitality businesses clustered near the city gates, strategically placed for travelers — merchants, sailors, and those breaking their journey overnight on the way to other destinations. Not every visitor needed such services, however. Wealthier Romans often stayed with friends or relied on networks of hospitae (“hosts”) in different cities, while some households rented out private rooms.

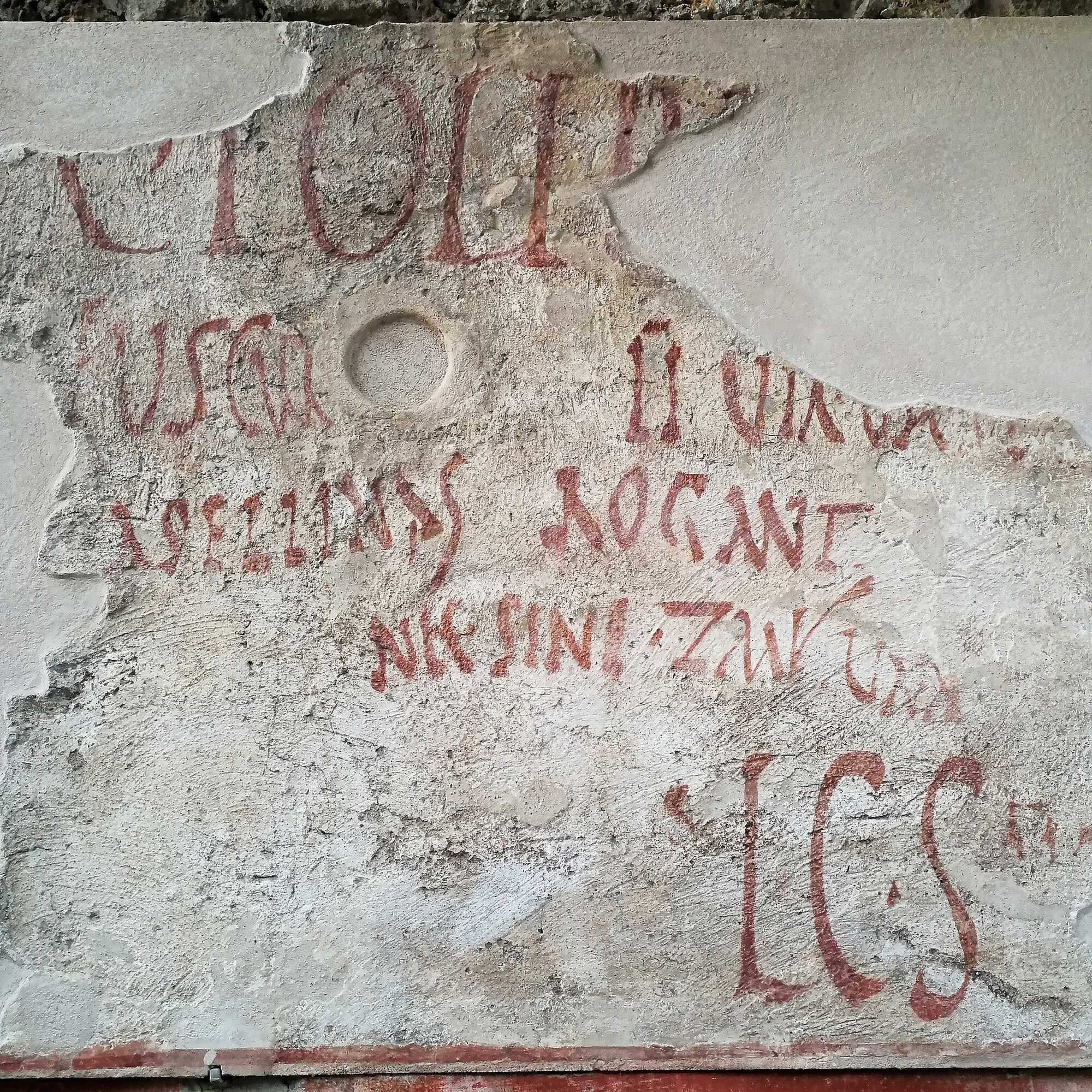

The inns near the gates quickly developed a reputation as haunts of less prestigious travelers. They were notorious for bedbugs, discomfort, violence, and danger. Apuleius and Petronius painted them as sordid places filled with poverty-stricken guests. Staff quality also varied, as a piece of graffiti from an inn in Pompeii humorously admits:

“We peed in the bed. I admit we did wrong, innkeeper. If you should ask why—well, there was no chamber-pot!”

Longer-term guests tended to lodge in hospitia within the city itself. This practice may have contributed to their reputation, as such establishments housed both transient travelers and poorer residents unable to rent homes. Petronius in the Satyricon even depicts an inn blending permanent tenants with short-stay customers.

The graffiti left behind gives a vivid glimpse into tavern life. At one inn, a disgruntled patron scrawled:

“Curses on you, innkeeper! What you sell us is water, and you keep the wine for yourself!”

In another tavern, a soldier was painted holding out his cup to a servant, above which a witty request was written:

“Just one drop of water to dilute my wine.”

Not all taverns bore a bad name. At one, the hostess Hedone advertised her menu openly: good wine for one as, better wine for two, and fine falernum for four. This same tavern was also the gathering place of the seribibi universi (“the late-night drinkers”), who even issued a political endorsement under their collective name.

Amorous graffiti also covered the walls. At a tavern, a visitor blended lines from Ovid and Propertius to declare:

“A fair skinned beauty taught me to despise dusky women. I will spurn them, if I can; if not … I will love them reluctantly.”

Such playful verses remind us that inns and taverns were not only places of wine and lodging, but also of humor, frustration, politics, and desire etched in everyday words.

From Samnite Houses to Mixed Businesses

One of the most famous examples of a Pompeian hospitium is the so-called House of Sallust, originally a grand Samnite residence later converted into a large hotel. Its layout was carefully adapted for commercial use. At entrance no. 5, the service counter could be reached from both the street and the atrium, maximizing custom.

Several bedrooms clustered around the atrium, while larger rooms off the northeast corner and the peristyle may have hosted indoor dining. Outside, a masonry triclinium, shaded by a pergola supported by two pilasters, provided a pleasant garden setting for meals. A nearby hearth prepared food for al fresco service.

Scholarship has noted that remodeling preserved the elegance of the house. Archaeologists described how guests could look through a broad picture window in the tablinum, raised three steps above the rest of the floor, to view the garden. On the back wall a painting extended the vista, showing columns, garlands, fountains, and birds as if continuing the real greenery outside.

Elsewhere in the city, establishments varied from modest to elaborate. Across from a larger hospitium, a small inn nonetheless boasted of its triclinium and displayed a striking wall painting of an elephant caught in the coils of a serpent and rescued by a pygmy.

Just inside the Porta Ercolano, a compact caupona offered a garden triclinium and rented rooms upstairs, though it lacked a counter with dolia and so either served cold meals or sourced food from elsewhere.

A more humble example was the stabulum of Hermes, its entrance once decorated with a painting of the innkeeper himself pouring wine from an amphora into a dolium. The courtyard plan included stalls along the rear wall, three upstairs rooms for lodgers, and even latrines on both floors—an unusual feature for such a modest business. Adjoining was a tavern with a separate dining room.

Tabernae and popinae were everywhere in Pompeii. Over a dozen lined the busy Strada Stabiana and Via dell’Abbondanza, with more along the Strada Consolare, Via di Nola, and near the amphitheater, forum, and baths. Around fifty stood on corners of major intersections.

Some were simple: the single-room taberna, once linked to the House of the Menander, had a red-painted masonry counter with two dolia, a small hearth, and an upstairs apartment. Larger ones,had an L-shaped counter with three dolia, a stove, and a back room perhaps used for dining, connected by doorways to the adjoining House of the Matron.

Many establishments combined functions. One business seems to have been at once a hospitium, caupona, stabulum, and popina. A counter, stove, and display shelves fronted the entrance, while passages connected to latrines and neighboring inns.

Guest rooms, a triclinium, watering troughs, cart sheds, and animal stalls were all included, forming a hub for wagon drivers (statio mulionum) near the Porta Ercolano. This multifunctional design was typical of Pompeian ingenuity in squeezing as much as possible from limited space.

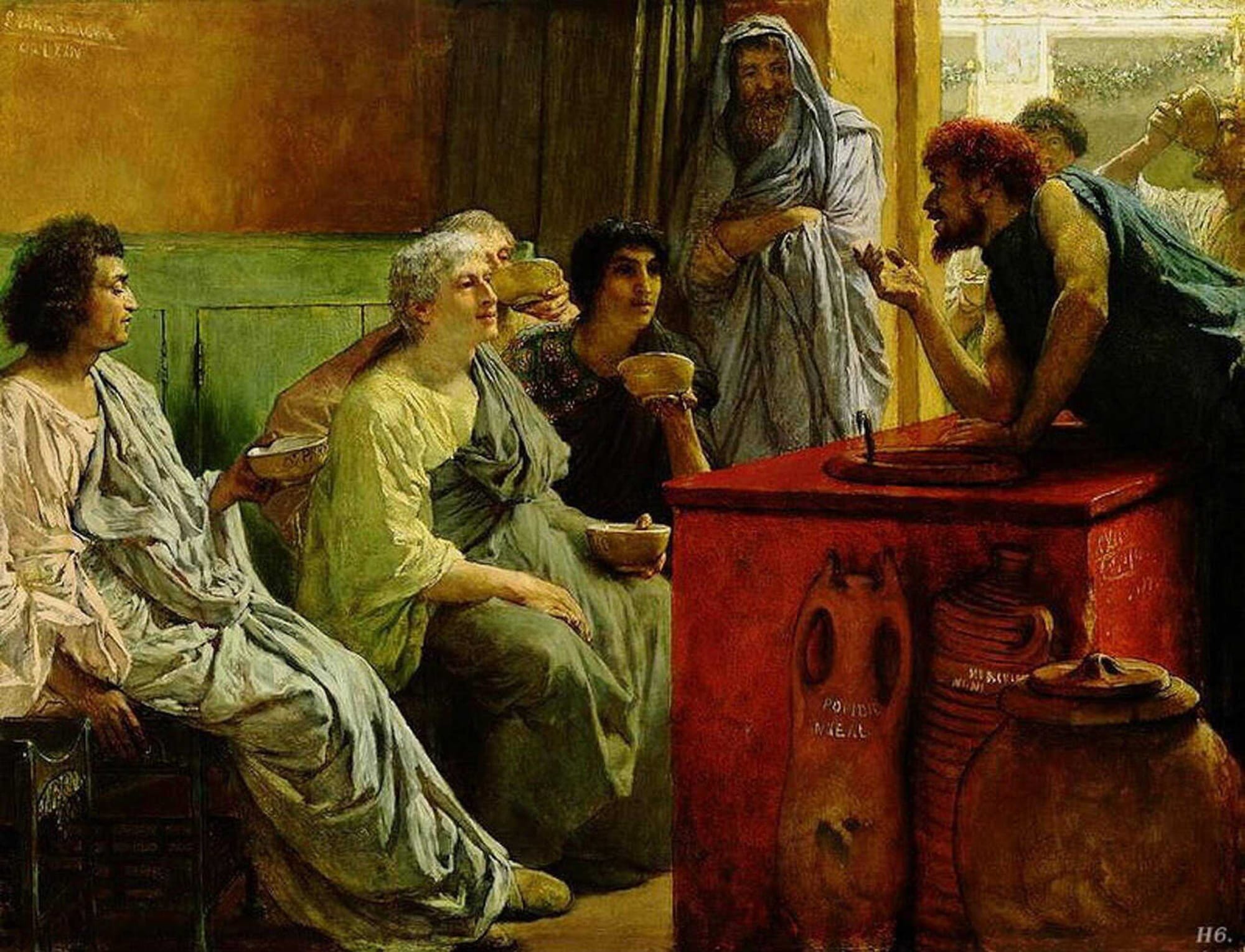

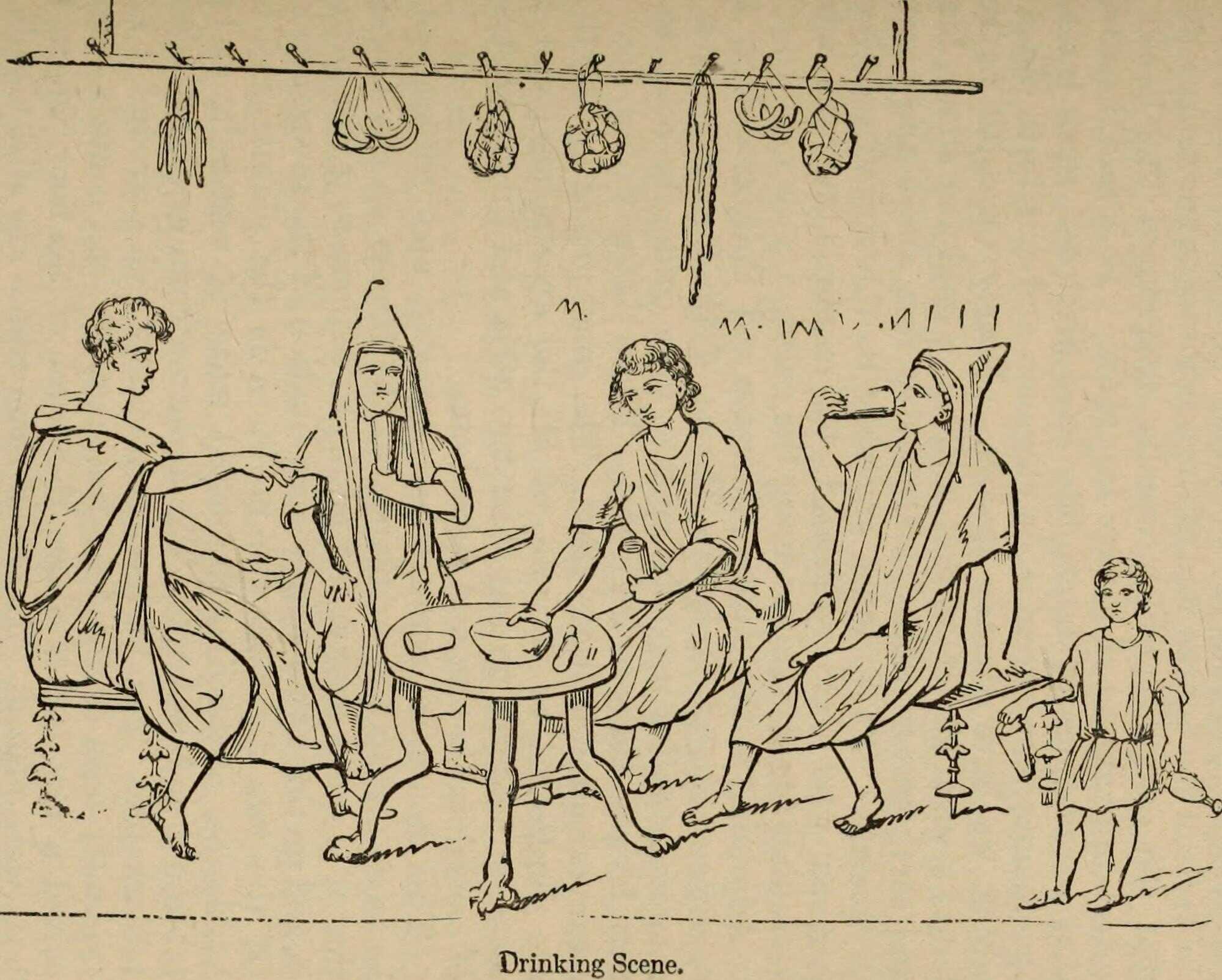

The fare in such establishments was simple. Diners sat at tables rather than reclining in triclinia, and paintings from an inn, show travelers seated around wooden tables, served by a puer cauponis (“serving boy”).

Both masonry dining tables and benches survive at sites like the Praedia of Julia Felix. Food quality must have varied. Horace once dismissed such eateries as uncta popina (“greasy taverns”).

Items on offer may have included eggs, goose liver paté, sow’s womb, poultry, game, pork, cheese, chickpeas, beans, cabbage in various forms, raw vegetables with vinegar, and beets, often strongly seasoned with garlic, pepper, and sauces. To entice customers, some foods were displayed outside in glass bowls filled with water, magnifying their size.

The authorities took notice of these venues. Emperors Tiberius, Claudius, Nero, and Vespasian all issued laws restricting the sale or display of certain prepared foods, especially meat and wine. Some believed these regulations were aimed at improving “public morality,” while others saw them as attempts to stifle political agitation in places where people gathered freely.

Yet these measures seem to have had little real effect: Pompeii’s taverns remained lively centers of social life. Even in later centuries, as Ammianus Marcellinus noted, Rome’s poor still spent their nights drinking and feasting in tabernae. Inns and taverns, however much maligned, were never silenced for long. (The world of Pompeii, edited by John J. Dobbins and Pedar W. Foss)

Wine Bars and Marble Counters as Silent Witnesses

The bars of Pompeii and Herculaneum are not only known from literature and graffiti, but also from the stone counters that survive in astonishing numbers. A detailed study by J.C. Fant, B. Russell, and S.J. Barker documented 49 bars in Pompeii and 8 in Herculaneum, recording more than 8,000 pieces of marble and stone used to face their counters.

The authors observed that “the marble-clad surfaces of the numerous bars or shops (thermopolia) of Pompeii and Herculaneum are a vast and hitherto untapped source of information about marble use beyond the confines of public building and élite houses.”

These counters were not hidden away but placed prominently, often facing the street, so that decoration itself served as an advertisement. At Pompeii, nearly half of all bars identified had marble cladding, and many employed colorful stones such as cipollino, giallo antico, portasanta, and africano.

Even rare materials from Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean were found, reused on these counters and displayed where customers could see them. Much of this marble was second-hand, salvaged from the renovation or demolition of public buildings and houses, particularly after the earthquake of AD 62.

The reuse of these stones shows that tavern owners were resourceful: marble cladding was not cheap, yet even modest establishments invested in it to project style and attract patrons. As the authors note, the counters testify both to the “pervasiveness of the wider pan-Mediterranean marble trade” and to the practical economics of recycling architectural materials.

Rather than being makeshift shops of ill-repute, Pompeii’s bars emerge from the archaeological record as established businesses integrated into the city’s economy, their marble counters standing as enduring proof of their role in urban life. (Marble use and reuse at Pompeii and Herculaneum: the evidence from the bars, by J.C. Fant, B. Russell and S.J. Barker)

From modest wooden booths to marble-clad counters, from graffiti-laden walls to imperial edicts, the inns and taverns of Pompeii and Rome reveal a society sustained as much by its street food and drinking houses as by its banquets and palaces. These spaces, often dismissed by elite writers, were in fact the lifeblood of urban life—places where travelers rested, locals gathered, and the empire’s commerce and camaraderie unfolded; one cup of wine at a time.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: