From Soldier to Sovereign: The Rise and Reign of Vespasian

The final ruler during the tumultuous Year of the Four Emperors, Vespasian established the Flavian dynasty, which governed the Roman Empire for 27 years.

The death of Nero in 68 CE plunged the Roman Empire into chaos, marking the beginning of a turbulent period known as the Year of the Four Emperors. In this time of political upheaval, four claimants—Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian—vied for control of the empire, each rising and falling in rapid succession.

Amid the bloodshed and instability, Vespasian, a pragmatic and seasoned general, emerged as the unlikely savior of Rome. His rise to power in 69 CE not only ended the anarchy, but also laid the foundation for the Flavian dynasty, bringing a much-needed era of stability and reform to the fractured empire.

The Stabilizer of an Empire in Chaos

Barbara Levick, in her book Vespasian, frames his story as one of remarkable success, underscored by medieval traditions that painted him as a noble emperor. In a fascinating tale from a 15th-century romance, Vespasian, suffering from leprosy, is healed by the handkerchief of St. Veronica and goes on to conquer Jerusalem, avenging Christ and converting the empire to Christianity.

The historical reality, while less mythical, is equally impressive. Vespasian rose from being a practical and unremarkable senator under the Julio-Claudian emperors to a seasoned military leader chosen by Nero to pacify Judaea. Commanding three legions and cooperating with the governors of Syria and Egypt, Vespasian found himself uniquely positioned to ascend to power during the chaotic Year of the Four Emperors.

The fall of Nero in June 68 marked the collapse of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, which had maintained stability for nearly a century. The power vacuum that followed saw a rapid succession of emperors—Galba, Otho, Vitellius—until Vespasian secured the throne. Tacitus aptly described this tumultuous year as “nearly Rome’s last,” but Vespasian’s calculated strategies and alliances ensured his survival and ultimate triumph.

Ascending to the principate in December 69, Vespasian inherited an empire in disarray, plagued by rebellion, demoralization, and financial strain. His approach was pragmatic rather than revolutionary; he adapted and restored the Augustan model of rule while focusing on rebuilding stability and projecting himself as a capable and traditional ruler.

His reign, along with those of his sons Titus and Domitian, marked the beginning of a new era.

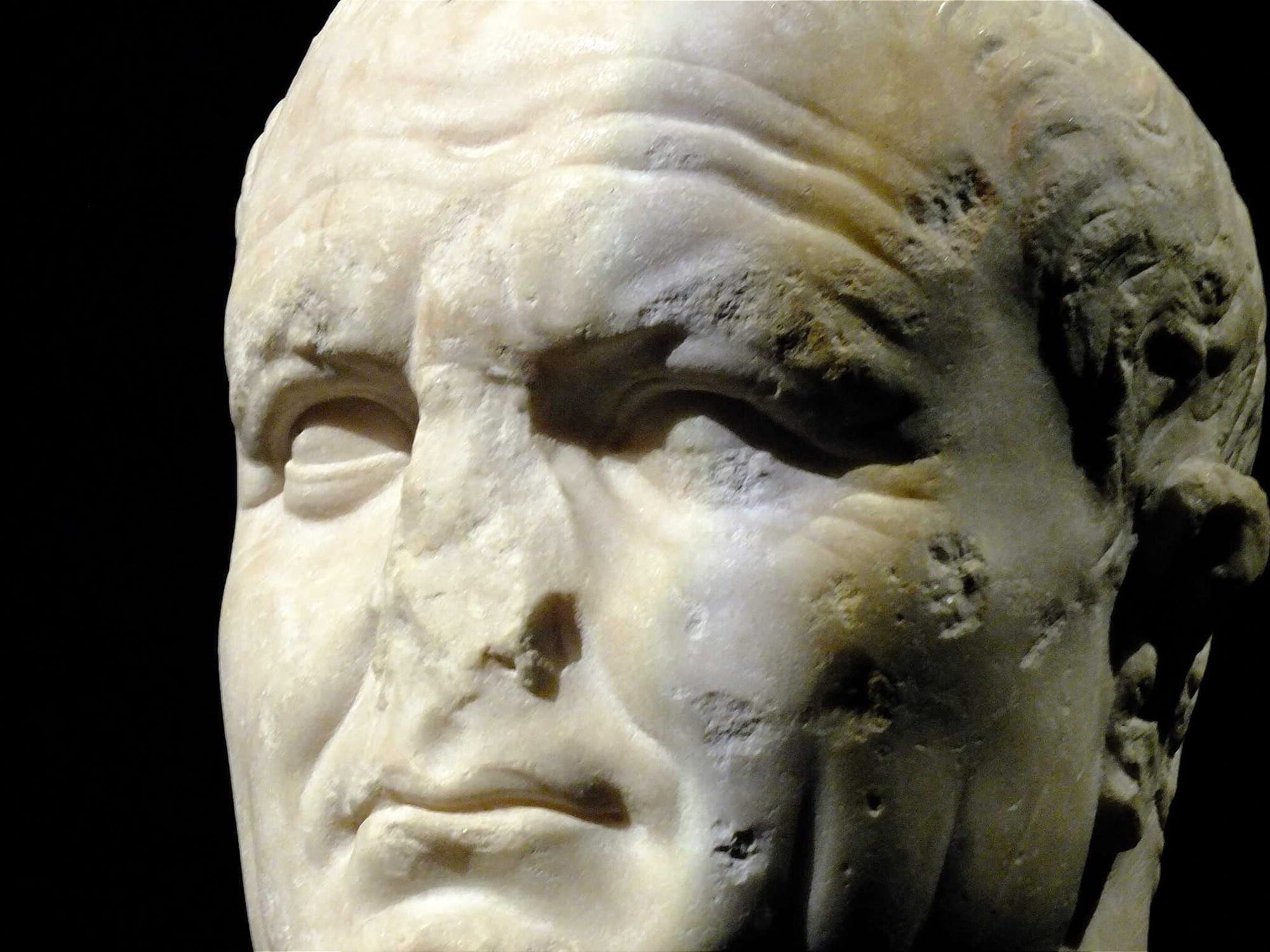

A damnatio memoriae of Nero; Emperor Vespasian’s bust, reworked from an original of Nero’s, maintaining some characteristics of the latter, like the deep-set eyes and side long hairline. Credits: failing_angel, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The Flavian dynasty set the stage for the relative peace and prosperity of the subsequent Nerva-Antonine period, often hailed as Rome’s Golden Age. Vespasian's legacy is multifaceted. While his restoration of stability is celebrated, his reign also reflected the emperor’s dual role as both a symbol of power and a servant of public expectation.

His measures to reform the military, curtail luxury, and restore Roman infrastructure carried both practical and propagandistic weight. Contemporary sources, though often shaped by Flavian propaganda, emphasize his efforts to address immediate crises while enhancing the moral and material stature of the state. Vespasian’s ability to blend pragmatism with a commanding public image secured his place as one of Rome’s great stabilizers in a time of profound upheaval.

The Rise of Vespasian: From Humble Beginnings to the Founding of a Dynasty

Vespasian's remarkable ascent from modest origins to Emperor of Rome is a testament to the permeability and complexity of Roman society during the transition from the Republic to the Principate.

Born in a Sabine village, he was the first of the Flavian family to achieve senatorial rank, rising to heights unimaginable for a man of his background. His family’s modest origins, often disparaged by detractors, included his grandfather, who was a centurion or tax collector, and his father, a moneylender in Helvetian territory. Suetonius notes that Vespasian’s family achieved respectability through financial enterprise and strategic marriages, even as rumors circulated to undermine their reputation.

Vespasian’s mother, Vespasia Polla, came from an influential Umbrian family, and her ambition played a significant role in her son’s success. She pushed him to seek higher office, despite his initial reluctance, and her connections provided vital support. Vespasian’s early career included military service in Moesia and the less prestigious posts of the Vigintivirate and quaestorship, where he faced setbacks but eventually secured the praetorship.

His marriage to Flavia Domitilla, a woman of contested freeborn status, further illustrates his pragmatic approach to alliances. Although the union elevated his social standing, financial benefits were delayed. Despite his modest beginnings, Vespasian’s family life remained intertwined with his Sabine roots, with the future emperor maintaining close ties to his homeland and the values of his upbringing.

Vespasian’s career reflects the broader social dynamics of his time. His rise from provincial obscurity to imperial power underscores the opportunities and challenges faced by "new men" in Roman society. By blending financial prudence, military competence, and familial ambition, Vespasian laid the foundations for the Flavian dynasty, which would stabilize and shape Rome in the aftermath of the chaotic Year of the Four Emperors.

From Humble Beginnings to Political Ascent

The early career of Vespasian, exemplifies the challenges and opportunities of navigating the Roman political system as a "new man." Born on November 17, AD 9, in the town of Falacrina near Reate, Vespasian’s early life was shaped by his paternal grandmother, Tertulla, as his parents were often away managing tax and banking ventures.

Despite a modest upbringing, Vespasian’s career trajectory eventually aligned with the senatorial path, although not without hesitation. Initially resistant to pursuing the latus clavus (a senatorial career marker), he later changed course, likely in the late 20s AD, and entered the cursus honorum.

“Vespasian was born in the country of the Sabines, beyond Reate, in a little country-seat called Phalacrine, upon the fifth of the calends of December [27th November], in the evening, in the consulship of Quintus Sulpicius Camerinus and Caius Poppaeus Sabinus, five years before the death of Augustus; and was educated under the care of Tertulla, his grandmother by the father's side, upon an estate belonging to the family, at Cosa.

After his advancement to the empire, he used frequently to visit the place where he had spent his infancy; and the villa was continued in the same condition, that he might see every thing about him just as he had been used to do.

And he had so great a regard for the memory of his grandmother, that, upon solemn occasions and festival days, he constantly drank out of a silver cup which she had been accustomed to use.”

Suetonius, Vita Divi Vespasiani - The life of Vespasian

Vespasian’s first official role was likely as a member of the vigintivirate, a minor administrative office that was a traditional step for aspiring senators. He then served as a tribunus laticlavius in Thrace, a posting that marked him as a promising military officer. By 35 AD, Vespasian was appointed quaestor in the province of Crete-Cyrene, a role focused on financial administration, though considered less prestigious.

Upon completing his term, he campaigned for the aedileship, which he achieved in 38 AD after suffering an initial defeat (repulsa). This role, primarily concerned with the maintenance of streets and public spaces, fit Vespasian’s practical approach and gained him visibility under Emperor Caligula’s rule. In 39 AD, Vespasian advanced to the praetorship, marking a significant step in his political ascent.

However, his rise was not exceptionally rapid compared to contemporaries, such as Q. Veranius, who enjoyed greater favor. Vespasian’s advancement suggests a combination of persistence, strategic choices, and his ability to fulfill administrative and military roles effectively. (Vespasian and the partes Flavianae, by John Nicols)

These formative years laid the groundwork for his later successes, culminating in his eventual role as Emperor during one of Rome’s most tumultuous periods.

17th century marble bust from Florence, Italy, of the first Roman Emperor of the Flavian dynasty, Vespasian. Credits: Jebulon, Public domain

From Humble Origins to the Restorer of Rome

Vespasian’s rise to power marked a turning point in Roman history. Titus Flavius Vespasianus emerged from modest beginnings to become the founder of the Flavian dynasty. It was precisely his unpretentious origins and pragmatic approach to governance that would later define his reign as one of stability and restoration.

Vespasian’s reputation as a skilled military leader was solidified during his campaigns in Britain under Claudius and later in Judaea under Nero. His victories in Judaea, where he subdued a fierce revolt, earned him the loyalty of the legions and positioned him as a viable candidate during the chaotic Year of the Four Emperors in AD 69.

With support from the eastern provinces and key military leaders, Vespasian secured his claim to the throne. Suetonius highlights his pragmatic approach during this tumultuous time, noting that “Vespasian’s reputation rose to meet the demands of the Principate, where others had fallen short.”

Once in power, Vespasian faced the daunting task of restoring stability to an empire ravaged by civil war and financial ruin. The treasury, depleted after Nero’s reign and the subsequent conflicts, required immediate attention. Through rigorous taxation and fiscal reforms, Vespasian replenished Rome’s finances.

His efforts were both practical and symbolic, demonstrating his commitment to the empire's recovery. Suetonius recounts how Vespasian humorously defended his imposition of taxes on public urinals, quipping, “Money does not stink,” a phrase that became emblematic of his straightforward pragmatism.

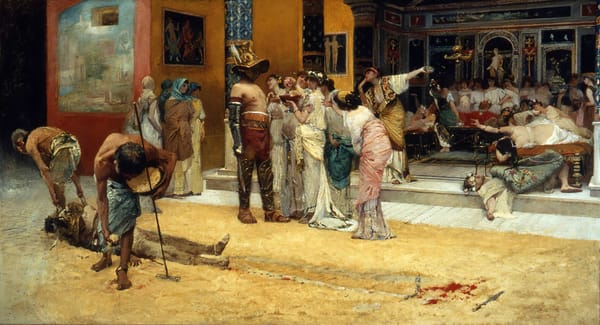

Public works became a cornerstone of Vespasian’s reign. He initiated the construction of the Colosseum, a grand amphitheater funded by spoils from the Jewish War, which served as both a symbol of Flavian power and a gift to the Roman people. He also restored temples, repaired infrastructure, and established the Temple of Peace, emphasizing his role as a restorer of Rome’s physical and moral fabric.

Suetonius observes that these projects reflected Vespasian’s dual aims: “to restore stability to a tottering state and to enhance its lustre.”

“He resolved upon rebuilding the Capitol, and was the foremost to put his hand to clearing the ground of the rubbish, and removed some of it upon his own shoulder.

And he undertook, likewise, to restore the three thousand tables of brass which had been destroyed in the fire which consumed the Capitol; searching in all quarters for copies of those curious and ancient records, in which were contained the decrees of the senate, almost from the building of the city, as well as the acts of the people, relative to alliances, treaties, and privileges granted to any person.”

Suetonius, Vita Divi Vespasiani - The life of Vespasian

Vespasian also utilized propaganda to solidify his legitimacy. Coins and monuments depicted him as a bringer of peace and stability, linking his rule to the ideals of Augustus. His humility and humor, however, set him apart from his predecessors.

According to Suetonius, Vespasian never allowed imperial flattery to corrupt him and often joked about his origins, once remarking that he was “just a Sabine farmer elevated by fate.” This self-awareness endeared him to the Roman populace and helped maintain his image as a relatable and just ruler.

"...He likewise erected several new public buildings, namely, the temple of Peace near the Forum, that of Claudius on the Coelian mount, which had been begun by Agrippina, but almost entirely demolished by Nero; and an amphitheatre in the middle of the city, upon finding that Augustus had projected such a work."

Suetonius, Vita Divi Vespasiani - The life of Vespasian

Despite his practical governance, Vespasian faced challenges. His efforts to discipline the military and curb luxury among the elite were met with resistance. Yet, his ability to balance autocratic authority with public engagement ensured his success. Suetonius credits him with fostering a clearer understanding of the emperor’s role and strengthening the senate’s position, laying the groundwork for a more stable imperial system.

Vespasian’s reign lasted ten years, during which he not only restored Rome’s stability but also set a precedent for his successors, Titus and Domitian. His emphasis on pragmatic leadership, fiscal responsibility, and public works marked the Flavian dynasty as a period of recovery and renewal. Suetonius encapsulates his legacy, stating that “through acts of restoration and generosity, Vespasian presented himself as a ruler for the people, exemplifying the ideal of a noble emperor.”

In the end, Vespasian’s life and reign epitomize the transformation of Rome from chaos to order. His ability to bridge the gap between humble origins and imperial grandeur, combined with his humor and practicality, ensured his place among Rome’s greatest leaders.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: