Emperor Titus, “Darling of Mankind”

Feared as another Nero, Titus surprised Rome by becoming one of its most beloved emperors. In just two years, he faced Vesuvius, fire, and plague—emerging as a ruler praised for generosity, diplomacy, and a transformation still debated today.

When Titus Flavius Vespasianus succeeded his father in 79 CE, Rome gained a ruler celebrated for his generosity, military skill, and personal charm. Yet his short reign was overshadowed by calamities of almost biblical scale—the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, a devastating fire in the capital, and a deadly plague.

Known as the conqueror of Jerusalem and the patron who completed the Colosseum, Titus became a symbol of imperial benevolence in the face of disaster. Ancient historians like Suetonius called him deliciae generis humani—the “darling of mankind”—a reputation that has endured for nearly two millennia, even as modern scholarship revisits the politics and propaganda behind his image.

Heir, Protector, and Enigma of the Flavian Age

Titus Flavius Vespasianus the Younger—known simply as Titus—holds a special place in Flavian history. As the first Roman emperor to follow his own father on the throne, he was, until the time of Marcus Aurelius, arguably the most thoroughly prepared successor. For nearly a decade, he served not only as heir-apparent but also, in Suetonius’ words:

“From that time on he never ceased to act as the emperor's partner and even as his protector.

He took part in his father's triumph and was censor with him.

He was also his colleague in the tribunicial power and in seven consulships.

He took upon himself the discharge of almost all duties, personally dictated letters and wrote edicts in his father's name, and even read his speeches in the senate in lieu of a quaestor.”

Suetonius, The Life of Titus

Yet this role had a darker aspect: as praetorian prefect—an almost unheard-of appointment for a senator—he acted as his father’s chief of security, displaying an arrogance and ruthlessness that made many fear the moment of his accession.

Much about his life remains uncertain, from his year of birth and the timeline of his two marriages, to the identity of Julia’s mother, his surviving daughter.

Roman Emperor Titus portrayed as a Roman general. Credits: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC 2.0

Questions linger over his celebrated liaison with the foreign-born Berenice, his stance toward his brother Domitian, and the circumstances of his sudden death after a short reign marked by catastrophe: the eruption of Vesuvius, a major fire in Rome, and a mysterious epidemic. These gaps and ambiguities continue to draw historians, offering fertile ground for fresh interpretations, new evidence, and even entirely new theories.

Courtly Education, Marriages, and the Making of an Heir

Suetonius opens his Life of Titus by recording that Vespasian’s eldest son was born on December 30, 41 CE, in a modest house likely located in the Campus Martius. This detail suggests Vespasian’s finances were strained at the time—something not unusual in his life.

Yet the date is almost certainly wrong: later in the same work (Tit. 11), Suetonius notes that Titus died on September 13, 81, two years, two months, and twenty days after Vespasian, and in the forty-second year of his life. This means he had already turned forty-one, placing his birth at the end of 39 CE. Cassius Dio (66.18.4; 66.26.4), generally reliable for such chronology, supports this earlier date.

“He was born on the third day before the Kalends of January, in the year memorable for the death of Gaius, in a mean house near the Septizonium and in a very small dark room besides; for it still remains and is on exhibition.”

“He died in the same villa as his father, on the Ides of September, two years, two months, and twenty days after succeeding him, in the forty-second year of his age.”

Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, The Life of Titus

“He had ruled two years, two months, and twenty days, as has been stated, and had lived thirty-nine years, five months, and twenty-five days.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History 66.26.1–2

By late 39, Vespasian’s senatorial career was advancing—he probably became praetor in 40—though it was marked by political hazards. A sycophantic speech in support of Caligula’s reprisals for a 39 CE conspiracy in Germany earned him the lasting enmity of Agrippina the Younger. Despite this, he maintained good relations with Claudius and the influential freedman Narcissus, leading to his appointment in 42 to command Legio II Augusta in Germany, which in 43 joined the invasion of Britain.

Vespasian distinguished himself in the conquest of southern and southwestern Britain (43–47), and Titus, then seven years old, was educated at court alongside Claudius’ heir Britannicus. Suetonius’ account of their close friendship may be somewhat embellished, but, as Levick notes, it was verifiable and thus likely accurate.

“He was brought up at court in company with Britannicus and taught the same subjects by the same masters.

At that time, so they say, a physiognomist was brought in by Narcissus, the freedman of Claudius, to examine Britannicus and declared most positively that he would never become emperor; but that Titus, who was standing near by at the time, would surely rule.

The boys were so intimate too, that it is believed that when Britannicus drained the fatal draught, Titus, who was reclining at his side, also tasted of the potion and for a long time suffered from an obstinate disorder.

Titus did not forget all this, but later set up a golden statue of his friend in the Palace, and dedicated another equestrian statue of ivory, which is to this day carried in the procession in the Circus, and he attended it on its first appearance.”

Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, The Life of Titus

Suetonius also praises Titus’ precocious talents—an exceptional memory, mastery of civil and military arts, fluency in Latin and Greek, and musical skill—though he also notes a more dubious ability: expertise in shorthand and forging handwriting.

“Even in boyhood his bodily and mental gifts were conspicuous and they became more and more so as he advanced in years.

He had a handsome person, in which there was no less dignity than grace, and was uncommonly strong, although he was not tall of stature and had a rather protruding belly.

His memory was extraordinary and he had an aptitude for almost all the arts, both of war and of peace.

Skilful in arms and horsemanship, he made speeches and wrote verses in Latin and Greek with ease and readiness, and even off-hand.

He was besides not unacquainted with music, but sang and played the harp agreeably and skilfully.

I have heard from many sources that he used also to write shorthand with great speed and would amuse himself by playful contests with his secretaries; also that he could imitate any handwriting that he had ever seen and often declared that he might have been the prince of forgers.”

Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, The Life of Titus

After Claudius’ marriage to Agrippina in 49, Vespasian’s career slowed, but Titus appears to have remained at court until Britannicus’ death in 55. His activities between then and 67 are obscure, though Suetonius states that he served as a military tribune in Germany and Britain (ca. 57–60 or 60–63), winning praise in both theaters. He later entered the legal profession and married Arrecina Tertulla, daughter of the former praetorian prefect M. Arrecinus Clemens, likely of Julian descent. Their daughter, Flavia Julia, may have been born shortly before Tertulla’s death in late 64.

Titus then wed Marcia Furnilla, from a distinguished senatorial family, who bore him another daughter who died in infancy. When Furnilla’s uncle, Q. Marcius Barea Soranus, was condemned on false charges in 66, Titus quickly divorced her—almost certainly to preserve favor with Nero. Around this time, he held a quaestorship, officially entering the Senate.

Up to late 66, Titus’ career followed a conventional upper-class path. Notably absent from most accounts is his mother, Flavia Domitilla, mentioned only by Suetonius as a woman of humble origins who bore Vespasian two sons and a daughter.

Both she and her daughter (born after Domitian in 51) had died before Vespasian’s accession in 69. Domitilla’s father, Flavius Liberalis, was of modest status, though possibly distantly related to Vespasian. Unlike the forceful Vespasia Polla, whose caustic remarks drove her younger son into politics, Domitilla appears to have exerted no discernible influence, good or bad, on Titus’ life.

Titus and the Jewish War: From Privileged Legate to Flavian Heir

The outbreak of the Jewish revolt in the spring of 66 CE presented an unexpected opportunity for the Flavians. Despite his known distaste for Nero’s artistic pursuits, Vespasian was chosen to lead Rome’s military response—a decision likely rooted in his proven record, political reliability, and humble origins. By the year’s end, Vespasian secured command in Judea and Syria, appointing his 27-year-old son Titus as legate of Legio XV Apollinaris.

In the campaigns of 67 CE, Titus quickly emerged as the favored subordinate among legion commanders, leading key assaults at Jotapata, Japha, Tarichaeae, Gamala, and Gischala. His inexperience showed, however, when he was deceived by Gischala’s rebel leader, allowing a dangerous escape to Jerusalem. While bold and charismatic, he lacked his father’s caution and strategic restraint.

In 68 CE, political upheavals in the West slowed military operations. Titus undertook a delicate diplomatic mission to reconcile Vespasian with C. Licinius Mucianus, governor of Syria—succeeding through tact and personal charm. When Galba replaced Nero, Vespasian sent Titus on another mission to win the new emperor’s favor. This journey was cut short in Corinth upon news of Galba’s assassination and the rise of Otho and Vitellius.

According to Tacitus, Titus already considered the prospect of a Flavian bid for power, an idea he likely conveyed to Vespasian and Mucianus. The plan was postponed until the civil conflict in Rome resolved, but by mid-69 the “Mount Carmel conference” set the Flavian strategy in motion. Vespasian moved to secure Egypt’s grain supply, Mucianus advanced west, and Titus assumed supreme command in Judea.

Returning to Jerusalem in spring 70 CE, Titus launched the siege that culminated in the city’s fall and the destruction of the Temple. While supported by the experienced Tiberius Julius Alexander as chief of staff, Titus’ leadership style—reckless personal bravery and severe reprisals—drew criticism for causing unnecessary casualties and displaying excessive brutality. His troops hailed him “Imperator” during the Temple’s destruction, but official inscriptions made clear he acted under Vespasian’s authority.

Following the victory, Titus managed a tense diplomatic encounter with Parthian envoys at Zeugma, before returning to Rome in mid-71. His shared triumph with Vespasian symbolized both military success and dynastic consolidation. Granted tribunician power from July 1, 71, Titus became the designated heir and, as Vespasian’s “partner and protector,” took on the regime’s less popular tasks—reinforcing his position at the heart of Flavian power while shaping the imperial image.

Titus and Berenice: Passion, Politics, and Palace Scandal

Julia Berenice, great-granddaughter of Herod the Great, was a powerful and controversial figure in the politics of the Eastern Mediterranean. Sister to King Agrippa II, she acted as his de facto consort and wielded influence in Rome’s eastern client network.

By the time Titus met her in 67 CE at Caesarea Philippi, she was almost forty—beautiful, wealthy, and politically seasoned. Titus, then twenty-seven, was drawn to her allure and status. While his relationships, both with women and young male companions, reflected the sexual fluidity common in Rome’s elite circles, Berenice stood out as a partner of prestige and intrigue.

Rumors of Titus’ tastes in pleasure—lavish late-night parties, entertainers, eunuchs, and handsome slave companions—were recorded by Suetonius, while ancient gossip also speculated about his closeness to the influential governor Mucianus. But it was his bond with Berenice that became most visible.

“Besides cruelty, he was also suspected of riotous living, since he protracted his revels until the middle of the night with the most prodigal of his friends; likewise of unchastity because of his troops of catamites and eunuchs, and his notorious passion for queen Berenice, to whom it was even said that he promised marriage.

He was suspected of greed as well; for it was well known that in cases which came before his father he put a price on his influence and accepted bribes.

In short, people not only thought, but openly declared, that he would be a second Nero.

But this reputation turned out to his advantage and gave place to the highest praise, when no fault was discovered in him, but on the contrary the highest virtues.”

Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, The Life of Titus

Tacitus noted that during his 69 CE voyage to Rome, Titus was widely believed to have turned back east out of passion for her. Their association deepened after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE, where Titus’ military triumph was paired with an increasing taste for luxury and self-indulgence.

When Berenice and Agrippa arrived in Rome in 75 CE, their relationship reignited. She moved into Titus’ section of the imperial palace, and contemporaries assumed they lived together. The pairing echoed Nero’s earlier attachment to the glamorous Calvia Crispinilla—a union of political partnership, spectacle, and whispered scandal. In the eyes of Rome’s elite, Berenice was both an exotic queen and a potential empress, embodying the blend of passion and politics that defined this chapter of Titus’ life.

From Heir to Emperor: Titus’ Final Years and Short Principate

As already mentioned at the beginning, in the closing decade of Vespasian’s reign, Titus acted as his father’s closest partner without holding the title of co-emperor. Sharing consulships, imperatorial salutations, and the censorship, he also served as praetorian prefect, managing much of the imperial administration.

While Vespasian retained ultimate control over policy, Titus gradually replaced Mucianus as chief aide, aligning with him in suppressing perceived political threats, including the “Stoic opposition.” The controversy surrounding his relationship with Berenice persisted, culminating in her dismissal—either during Vespasian’s final years, as Cassius Dio suggests, or immediately after Titus’ accession, as Suetonius claims.

By 79 CE, the prospect of Titus succeeding his father was met with unease, some fearing “another Nero.”

A bust of Titus from Utica. Credits: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC 2.0

That summer, the conspiracy of Caecina Alienus and Eprius Marcellus underscored this apprehension. Vespasian’s death in June brought Titus to power without challenge, but he quickly adopted a more sober, Vespasian-like public image. He cultivated good relations with the Senate, promised to avoid treason trials and executions, and won popular favor through new public works and lavish spectacles, including the hundred-day games inaugurating the Flavian Amphitheater.

Titus’ reign was defined by a series of disasters: the eruption of Vesuvius in 79, the great fire of Rome in 80, and a severe epidemic that followed. His personal involvement in relief efforts—refusing outside aid and spending lavishly on recovery—earned him praise as a caring and conscientious ruler. Yet, apart from these responses, little of note was recorded in the last year of his reign.

By mid-80, sources suggest he appeared withdrawn or depressed, and in September 81, while traveling to the Flavian family estate, he was struck by sudden fever. Believing his end was near, he lamented that he did not deserve to die. Ancient rumor quickly cast suspicion on Domitian’s role in his brother’s death, a suspicion that has never been proven but has remained part of the enduring intrigue surrounding Titus’ final days. (The Emperor Titus, by Charles Leslie Murison, in A Companion to the Flavian Age of Imperial Rome, edited by Andrew Zissos)

Reassessing Suetonius’s Titus: Panegyric, Paradox, and the Problem of Reputation

“Titus, of the same surname as his father, was the delight and darling of the human race; such surpassing ability had he, by nature, art, or good fortune, to win the affections of all men, and that, too, which is no easy task, while he was emperor; for as a private citizen, and even during his father's rule, he did not escape hatred, much less public criticism.

He was born on the third day before the Kalends of January, in the year memorable for the death of Gaius, in a mean house near the Septizonium and in a very small dark room besides; for it still remains and is on exhibition.”

Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, The Life of Titus

Ancient historians differed sharply in their verdicts, and later scholarship has continued to wrestle with the paradox of Titus’ reign.

A statue of Emperor Titus. Credits: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC 2.0

Suetonius’ Life of Titus has often been dismissed as one of the weakest of the Caesars, its panegyrical tone seemingly at odds with his usual structure. Critics have long noted its striking division into two halves: a record of Titus’ vices before becoming emperor, followed by unreserved praise of his principate.

Yet the biography is more carefully constructed than it appears. Suetonius frames Titus within the Flavian narrative arc—Vespasian’s rise, Titus at the dynasty’s peak, and Domitian’s decline—while drawing thematic parallels with earlier emperors, especially Augustus. Central to Suetonius’ approach is the question of transformation: how did a man feared as another Nero at his accession win universal affection while reigning?

This issue, shared with other imperial historians, was a point of contention well into late antiquity. Cassius Dio, for example, speculated whether Titus’ virtue was genuine or merely a short-lived effect of a brief reign. Defenders likened him to Augustus—both ruthless in youth but ultimately admired—while detractors claimed only his early death spared Rome from tyranny.

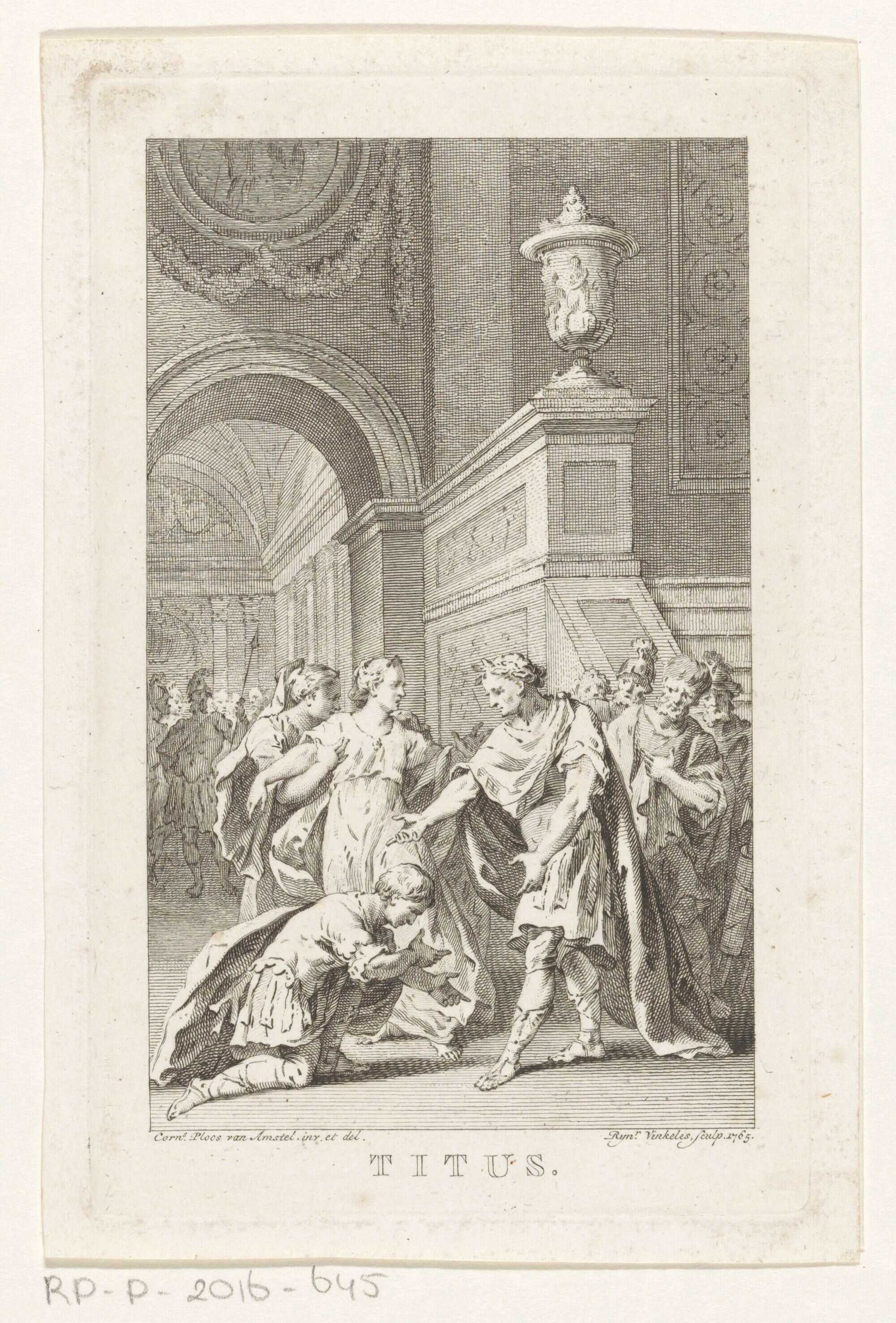

Image #1: Franciszek Smuglewicz’s painting of Emperor Titus granting rights to Rome. Public domain Image #2: Inscription commemorating the restoration of Surrentum's horologium (town's clock) by the Emperor Titus after the earthquake of AD 79. Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

“His satisfactory record may also have been due to the fact that he survived his accession but a very short time, for he was thus given no opportunity for wrongdoing.

For he lived after this only two years, two months and twenty days—in addition to the thirty‑nine years, five months and twenty‑five days he had already lived at that time.

In this respect, indeed, he is regarded as having equalled the long reign of Augustus, since it is maintained that Augustus would never have been loved had he lived a shorter time, nor Titus had he lived longer.

For Augustus, though at the outset he showed himself rather harsh because of the wars and the factional strife, was later able, in the course of time, to achieve a brilliant reputation for his kindly deeds; Titus, on the other hand, ruled with mildness and died at the height of his glory, whereas, if he had lived a long time, it might have been shown that he owes his present fame more to good fortune than to merit.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History 66.26.1–2

Suetonius rejects such cynicism entirely. He ignores the notion that a longer reign might have revealed darker traits, instead portraying Titus’ death as an irreparable loss for mankind. His explanation for the emperor’s popularity rests on the interplay of three classical categories—ingenium (natural disposition), ars (acquired skill), and fortuna (fortune)—a framework also reflected in Tacitus’ depiction of Titus as:

"capable of the highest fortune, able to reconcile rivals through nature and art, and more self-controlled as ruler than as heir."

“The report gained the more credit from the genius of Titus himself, equal as it was to the most exalted fortune, from the mingled beauty and majesty of his countenance…”

Tacitus, Histories Book 2, Chapter 1

In Suetonius’ telling, Titus’ reign required no redemption by premature death; his character and abilities alone secured his place as one of Rome’s most beloved emperors. (Another look at Suetonius' Titus, by W. Jeffrey Tatum, in Suetonius the Biographer: Studies in Roman Lives, edited by Tristan Power & Roy K. Gibson)

Vitellia is a central character in Mozart's La clemenza di Tito, where a dramatic account of her life has her attempt to assassinate Titus, after he declares his love for the Jewish princess Berenice. The opera is set in 79.

“On his death, the common people, in their grief, likened him to the gods, and hailed him as ‘the delight and darling of the human race.

He died in the same villa as his father, on the Ides of September, two years, two months, and twenty days after succeeding him, in the forty-second year of his age.

He was so much lamented by the people that it was said he had been taken from them not for his own good, but for theirs.”

Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, The Life of Titus

Titus’ principate, brief yet eventful, remains one of Rome’s enduring paradoxes. To some, his reign’s brevity preserved his reputation; to others, it revealed his true nature at its best. Whether through innate character, cultivated skill, or sheer fortune, he emerged from suspicion to be mourned as deliciae generis humani—the “darling of mankind.” In Suetonius’ account, his death was not a reprieve from potential tyranny, but a loss for the empire, sealing the image of a ruler whose short time in power left a legacy outlasting the Flavian dynasty itself.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: