Whispers on the Walls: Graffiti as a Voice of Ancient Rome

For tens of thousands of years, people have been leaving their marks on the walls. How was street art during the Empire perceived?

Beneath the grandeur of marble temples and towering aqueducts, a different kind of Roman voice survives—etched, painted, and scratched onto walls. Graffiti, often dismissed as vandalism in the modern world, was a vibrant form of expression in ancient Rome, offering an unfiltered glimpse into the lives of ordinary people.

From witty insults and love declarations to political slogans and business advertisements, these messages provide a unique lens through which to view the daily rhythms, aspirations, and struggles of Roman society. Nowhere is this art of the people more vivid than in Pompeii, where the preserved graffiti on walls, taverns, and public spaces reveals a world bustling with humor, rivalry, and human connection.

As A. J. Peden, in “The Graffiti of Pharaonic Egypt” says, graffiti serves as a means of expression that is both personal and unrestricted, unbound by the usual societal constraints that often limit individuals from freely sharing their thoughts. These often unpolished inscriptions provide fascinating glimpses into the lives of their creators and the cultural framework of the society they inhabit.

Ancient Graffiti: Unveiling the Voices of the Past

According to Peter Keegan in “Graffiti in Antiquity”, modern society defines graffiti as “writings or drawings scribbled, scratched, or sprayed illicitly on a wall or other surface in a public place.” (Oxford Dictionaries)

This definition covers a wide range of texts, such as single letters, phrases, and sentences, as well as artistic expressions like pictures, diagrams, or identifying marks like “tags,” “throw-ups,” and “stencils.” Graffiti can also involve various techniques—hasty writing, marking with sharp tools, or applying colored substances—and can appear on different surfaces, often man-made and public.

However, the modern association of graffiti with illegality and public spaces contrasts sharply with ancient attitudes toward this practice.

Roman theatre mask graffiti in Lisbon. Credits: Roman Empire Times

In antiquity, the legality of graffiti depended on the consent of the property owner. Modern laws, which consider graffiti a punishable offense unless permission is granted, have parallels in the ancient world. Evidence shows that permission to write or draw on property in ancient times was broader and less formally defined.

Graffiti from the ancient Mediterranean is widespread, appearing not only on civic structures like arenas, temples, and baths but also on columns, doorposts, and even steppingstones. In addition, private and domestic items such as pottery, metal objects, and wood were also commonly marked with graffiti, suggesting a society deeply integrated with this form of expression.

Despite occasional prohibitions, ancient graffiti flourished. For instance, a Pompeian inscription warns:

“If someone writes something here, may he rot and his name be pronounced no more”.

Similarly, at Rome, an inscription from a temple portico reads:

“Gaius Iulius Anicetus, at the behest of Sol, requests that no one inscribe or scribble on the walls or triclia [covered, porticoed chamber]”.

However, the sheer volume of surviving graffiti on both public and private structures suggests that these warnings were the exception rather than the rule.

Modern laws often view graffiti as a form of anti-social behavior, defined as activities causing harassment, alarm or distress. Political graffiti is typically exempt if deemed reasonable, but ancient criteria for offense or political commentary differed significantly.

At Pompeii, for instance, over 11,000 graffiti inscriptions survive, with roughly half found on domestic or occupational buildings such as houses, shops, and brothels. These markings were often made in full view of occupants and visitors, indicating a level of societal tolerance not typically seen today.

Tools used for graffiti, such as spray paint or markers, are regulated in modern contexts, but no such restrictions existed in antiquity. This absence highlights differences in how ancient societies produced and consumed meaning. Graffiti in antiquity often occupied shared spaces like communal latrines, theaters, tombs, and shrines.

The individuals creating these markings likely intended them for an audience, embedding their messages within broader social and cultural contexts. For example, inscriptions in Pompeii include political pamphlets, electoral posters, and even graffiti on amphorae and other pottery types.

These texts reveal an epigraphic culture deeply integrated into everyday life. Modern views on graffiti as inherently disruptive reflect a distinct perspective. In contrast, ancient graffiti emerged from deeply social patterns of behavior, serving as a medium for communication within communal spaces.

Historians today are well-positioned to analyze these markings, interpreting them as part of a vibrant epigraphic tradition. However, critical study of ancient graffiti remains limited. While philologists have examined the linguistic elements, and archaeologists the material contexts, efforts to integrate these perspectives remain sparse.

Graffiti’s freedom from conventional artistic and literary constraints makes it a compelling lens for studying ancient society. As Peter Keegan demonstrates, graffiti offers insights into the symbolic structures and human activities of the ancient Mediterranean. These markings, preserved across a variety of contexts, reveal the dynamic and multifaceted ways in which individuals interacted with their world and left their voices for posterity.

The Interplay of Graffiti and Historical Writing

Graffiti in the ancient world offers a fascinating window into the daily lives and cultural dynamics of its time. Unlike the modern perspective that often associates graffiti with vandalism or illicit public markings, these inscriptions were a profound form of personal and public expression.

They existed at the intersection of informal communication and historical record, complementing the more polished narratives of classical historians such as Livy, Tacitus, and Cassius Dio. Through graffiti, we gain insight into the sentiments, aspirations, and frustrations of ordinary individuals—voices that are often absent from official records.

These markings reveal the socio-political undercurrents of Ancient Rome, capturing moments of triumph, dissent, and cultural exchange, while simultaneously shedding light on pivotal events, key figures, and the evolving urban landscape. In this way, graffiti serves as a unique and invaluable complement to the formal historical accounts of antiquity, enriching our understanding of the complexities of Roman society.

Graffiti and Historical Context: Livy’s Perspective

Livy’s monumental Ab Urbe Condita traces Rome's evolution from its legendary foundation to its imperial dominance under Augustus. Though annalistic in nature, Livy’s narrative infused moral, religious, and social virtues into historical events. Graffiti parallels this approach by capturing important moments in Roman history from a grassroots perspective, often reflecting marginalized voices.

For instance, inscriptions from the Social War (91 BCE) in Pompeii include directives to defenders during emergencies. These inscriptions, known as eituns, highlight the localized military organization during a time of upheaval:

"Go by this route between the 12th Tower and the Salt Gate, where Maras Atrius, son of Vibius, gives instructions."

"Fight where Matrius, son of Vibius, is in charge."

These inscriptions not only delineate defensive strategies but also preserve the original names of city gates and districts, providing a rare glimpse into the urban and social fabric of the time.

Graffiti as Historical Evidence: Tacitus and the Pompeii Riot

Tacitus’ Annals recount events that intertwine with urban tensions and civic unrest. A notable episode is the violent clash between Pompeii and Nuceria during a gladiatorial show in 59 CE, escalating from verbal taunts to physical confrontation. Tacitus records the Senate’s decree banning gladiatorial games in Pompeii for a decade, underscoring the impact of these riots on local identity and economy.

Graffiti and frescoes complement Tacitus' account. A wall painting in the House of Anicetus depicts the chaos, with figures fighting within and outside the amphitheater. A chalk sketch on the House of the Dioscuri façade features a prisoner and a victorious gladiator holding a palm, accompanied by an inscription:

“Campanians, you perished together with the Nucerians in victory.”

Such depictions vividly illustrate how graffiti served as both a historical record and a medium for public commentary on significant events.

Cassius Dio’s Insights

Graffiti often played a role in shaping or reflecting political discourse. Cassius Dio’s Roman History recounts public dissatisfaction during Caesar’s rise to power. Graffiti addressed to Marcus Brutus, a perceived defender of Republican ideals, captures the mood of the populace:

“Would that you were living!”

“Brutus, you are sleeping.”

“You are not Brutus.”

Similarly, Dio reports a scathing inscription on a statue of Agrippina the Younger after her murder by Nero:

“I, I am ashamed of you; but you, do you not blush?”

These examples highlight graffiti’s role as a tool of political expression, often offering candid insights absent from official records.

Graffiti in the Histories of Ammianus Marcellinus

In his Res Gestae, Ammianus Marcellinus provides another lens through which to view graffiti’s historical significance. He recounts Constantine II’s suspicion of the oracle of Bes at Abydos, where individuals sought divine guidance. Graffiti found at the shrine supports Ammianus’ narrative, including a prayer by Artemidorus:

“May I not be wiped out.”

Graffiti often served as a subtle yet powerful tool for public commentary in ancient Rome, revealing the sentiments of the populace toward significant figures and policies. A striking example comes from Suetonius, who recounts public dissatisfaction with Emperor Domitian’s penchant for excessive building projects. One succinct inscription, etched in Greek on one of Domitian’s arches, read:

“It is enough.”

This brief yet impactful statement critiques Domitian’s monumental constructions, reflecting popular discontent with his self-aggrandizing tendencies. Through this simple phrase, we glimpse the frustrations of ordinary citizens, who used graffiti as a means to voice their resistance in an era where open dissent could carry serious consequences. Such inscriptions demonstrate how graffiti captured the undercurrents of public opinion, adding a valuable dimension to the study of Roman political and cultural life.

The Language of Love and Literary Aesthetics in Pompeian Graffiti

One of the most captivating aspects of Pompeian graffiti is its preoccupation with themes of love and sexuality. These wall inscriptions not only reveal a profound connection to the literary traditions of Rome but also shed light on the everyday thoughts and emotions of ancient Pompeians.

Found in both public and private spaces, Pompeian graffiti encompasses a wide range of sentiments, from playful declarations to deeply poetic expressions, offering a fascinating glimpse into the intersections of personal experience, education, and public discourse. In the Basilica of Pompeii, graffiti presents an array of emotions and styles. Some inscriptions lean toward the playful and romantic, such as:

"Mea vita, meae deliciae ludamus, parumper hunc lectum c[...]"

CIL 4.1781

Others are more straightforward expressions of affection:

"Caesius fidelis amat m[...]"

CIL 4.1812

Meanwhile, some carry a philosophical tone, reflecting on the nature of love and beauty:

"Nemo est bellus nisi qui amat mul[ier]em adu[lescentulus?"

CIL 4.1883

However, not all graffiti remains poetic or sentimental; many inscriptions take a sharp turn into the vulgar and humorous. For example:

"Narcissus fellator maximus"

CIL 4.1825a/b

Others showcase linguistic creativity, such as the neologism "irrumabiliter," presumably meaning "face-f***ingably" (CIL 4.1931). Despite their diversity, these inscriptions demonstrate a shared preoccupation with erotic themes, a central motif in Roman culture.

Beyond their explicit content, Pompeian graffiti often reveal a literary sensibility, intertwining personal sentiments with the stylistic and thematic elements of Roman poetry. For example, one inscription declares:

"Scribinti mi dictat amor mostratque cupido | ad peream, sine te si deus esse velim."

CIL 4.1928

These lines evoke the works of Ovid and other canonical elegists. The phrase "scribinti mi dictat amor" ("Love directs me as I write") mirrors Ovid’s use of Cupid as both inspiration and antagonist in the Amores.

However, unlike Ovid’s playful depiction of Cupid disrupting poetic meter, this graffiti positions the god as a guiding force, emphasizing the act of writing itself. The prominence of the participle "scribinti" at the start of the hexameter underscores the physical act of inscribing the poem, situating the writer firmly within the practice of creating material culture.

The graffiti also point to the broader cultural and educational practices of ancient Rome. The imagery of Cupid as a schoolmaster dictating verses recalls the pedagogical methods of Roman classrooms, where students copied prose and poetry as part of their training.

Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria highlights the moral and aesthetic goals of this practice, suggesting that selected passages should shape character and be memorable for their elegance. Although Quintilian disapproved of using Roman elegists like Propertius in education, the brevity and wit of their poetry often lent themselves well to graffiti.

For example, a Propertius line from Elegies –

"Now anger is fresh, now is the time to go away: once pain has faded, believe me, love will return"

— appears repurposed on a Pompeian street wall (CIL 6.13.19). Stripped of its original context, the line communicates a universal truth about time and healing, transcending its literary origins.

The graffiti’s fragmentary nature reflects a broader aesthetic tied to education and popular culture. In Roman schools, students learned poetry in short, memorable excerpts, a practice evident in the brevity and aphoristic tone of many inscriptions. This habit of isolating lines from their larger contexts allowed graffiti writers to imbue their texts with new meanings, repurposing canonical phrases for personal or communal expression.

A poignant example is CIL 4.5296, a longer love poem that combines literary sophistication with raw emotion. Its survival as graffiti attests to the blend of public and private, written and oral traditions that characterized Pompeii’s urban literary culture. The writer’s choice to inscribe their verse on a wall underscores the interplay between formal education, personal sentiment, and public display.

A Love Poem on Pompeii’s Walls

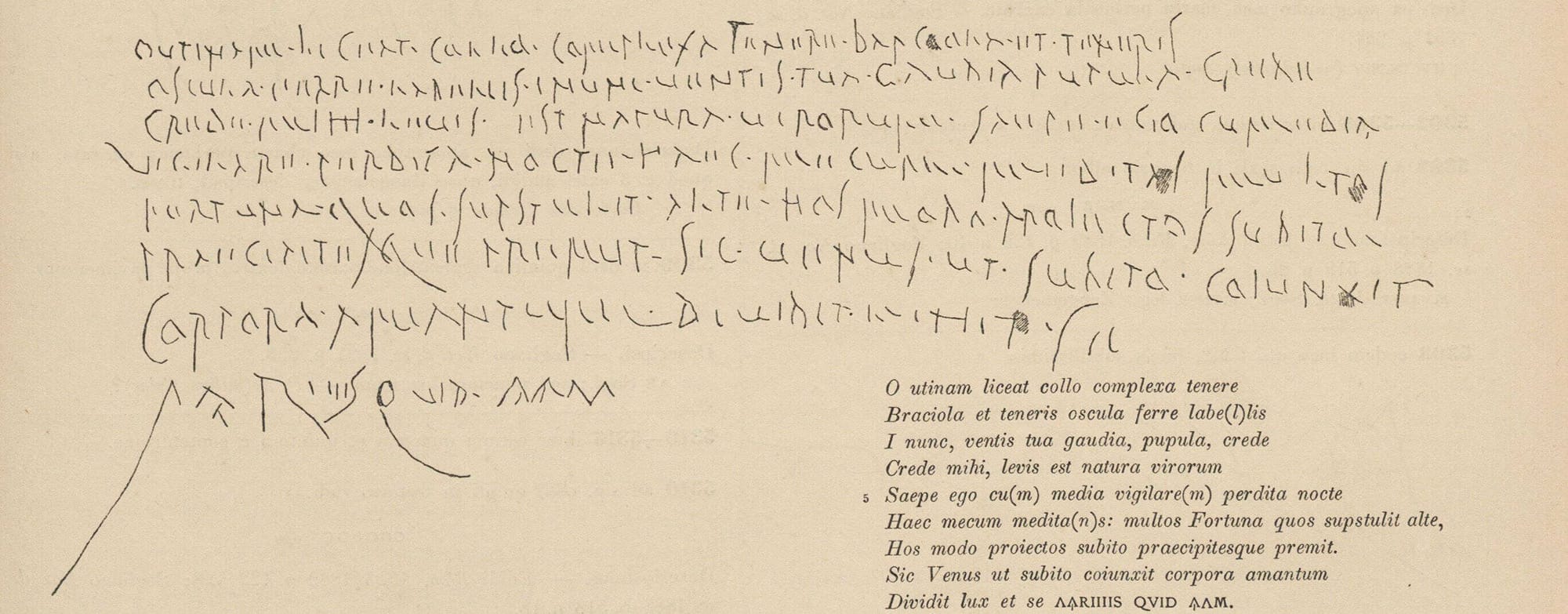

In 1888, archaeologists excavating a narrow alley in Pompeii’s ninth region discovered an intriguing piece of graffiti etched into the plaster wall of a hallway. This seven-line love poem, later cataloged as CIL 4.5296, immediately drew attention due to its literary qualities.

While the interior spaces beyond the hallway had yet to be unearthed, the text alone was enough to merit publication in that year’s excavation report. Antonio Sogliano, the report’s author, noted the poem’s irregular meter and identified parallels with classical literature, but his most striking observation was simple: “It is a woman who speaks.”

"Oh, would that it were permitted to grasp with my neck your little arms

as they entwine [it] and to give kisses to your delicate little lips.

Come now, my little darling, entrust your pleasures to the winds.

(En)trust me, the nature of men is insubstantial.

Often as I have been awake, lovesick, at midnight,

you think on these things with me: many are they whom Fortune lifted high;

these, suddenly thrown down headlong, she now oppresses.

Thus, just as Venus suddenly joined the bodies of lovers,

daylight divides them and if(?)..."

Despite some irregularities in spelling and grammar, the poem exhibits clear poetic ambition, blending elements of hexameter and elegiac couplets. A final line beneath the poem, reading "paries quid ama", appears to be a separate addition, possibly a quotation from Ovid’s Metamorphoses ("Wall, why do you stand in the way of lovers?"). Its differing handwriting suggests it was added later as a playful commentary on the love poem above.

The poem’s most debated aspect lies in its voice and gender. Two key elements—the vocative pupula (a feminine term of endearment) and the participle perdita (lovesick, feminine)—suggest that the speaker is female and that the addressee may also be female. This interpretation challenges traditional assumptions about gender roles and authorship in Roman graffiti.

Scholars have proposed various theories to explain this "gender trouble." Some argue that perdita could agree with nocte (night) rather than ego (I), allowing the speaker to be male. Others speculate that pupula refers to the poet’s own spirit rather than the poem’s beloved. Still others posit a change of speaker midway through the text, with pupula marking a shift to the beloved’s voice.

These debates reflect broader uncertainties about authorship in ancient graffiti. While graffiti often reflects the personal voice of its inscriber, it can also involve copying, adaptation, or creative reinterpretation of pre-existing texts. The literary qualities of CIL 4.5296 complicate the matter further, as its style suggests influence from Roman elegiac poetry, yet its context—a casual inscription on a wall—places it far from elite literary circles.

Graffiti and Roman Literacy

The ambiguity surrounding the gendered voice of CIL 4.5296 also highlights broader questions about literacy and authorship in ancient Rome. While evidence suggests that some Roman women could read and write, societal norms often attributed public inscriptions to men. Yet graffiti, with its informal and personal nature, provides a space where marginalized voices, including women’s, might surface.

Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans even portrays fictional women writing graffiti to assert their presence and desires, suggesting that the concept of female participation in this medium was not implausible. However, the lack of direct evidence complicates definitive claims about female authorship in Pompeian graffiti.

The interplay between formal literary influences and the informal context of graffiti underscores the complexity of Pompeian writing culture. Graffiti writers often adapted fragments of popular verse, reshaping canonical texts into personal and localized expressions. (Graffiti and the Literary Landscape in Roman Pompeii, by Kristina Milnor)

CIL 4.5296 exemplifies the rich intersection of public and private, personal and literary, in Pompeian graffiti. Whether composed by a woman or not, it offers a rare glimpse into the creative and emotional lives of ancient Pompeians, blending love, poetry, and public inscription in a way that challenges modern assumptions about authorship, gender, and literary tradition.

As a product of its time and place, this remarkable graffiti serves as a proof to the enduring power of poetic expression, in even the most unexpected corners of Roman society.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: