Sulla: Rome’s Reluctant Tyrant

Sulla marched on Rome, ruled by terror, and then did the unthinkable—he gave up absolute power. A paradox of reformer and tyrant, he reshaped the Republic through blood and law, leaving a legacy that foreshadowed Caesar and the emperors to come.

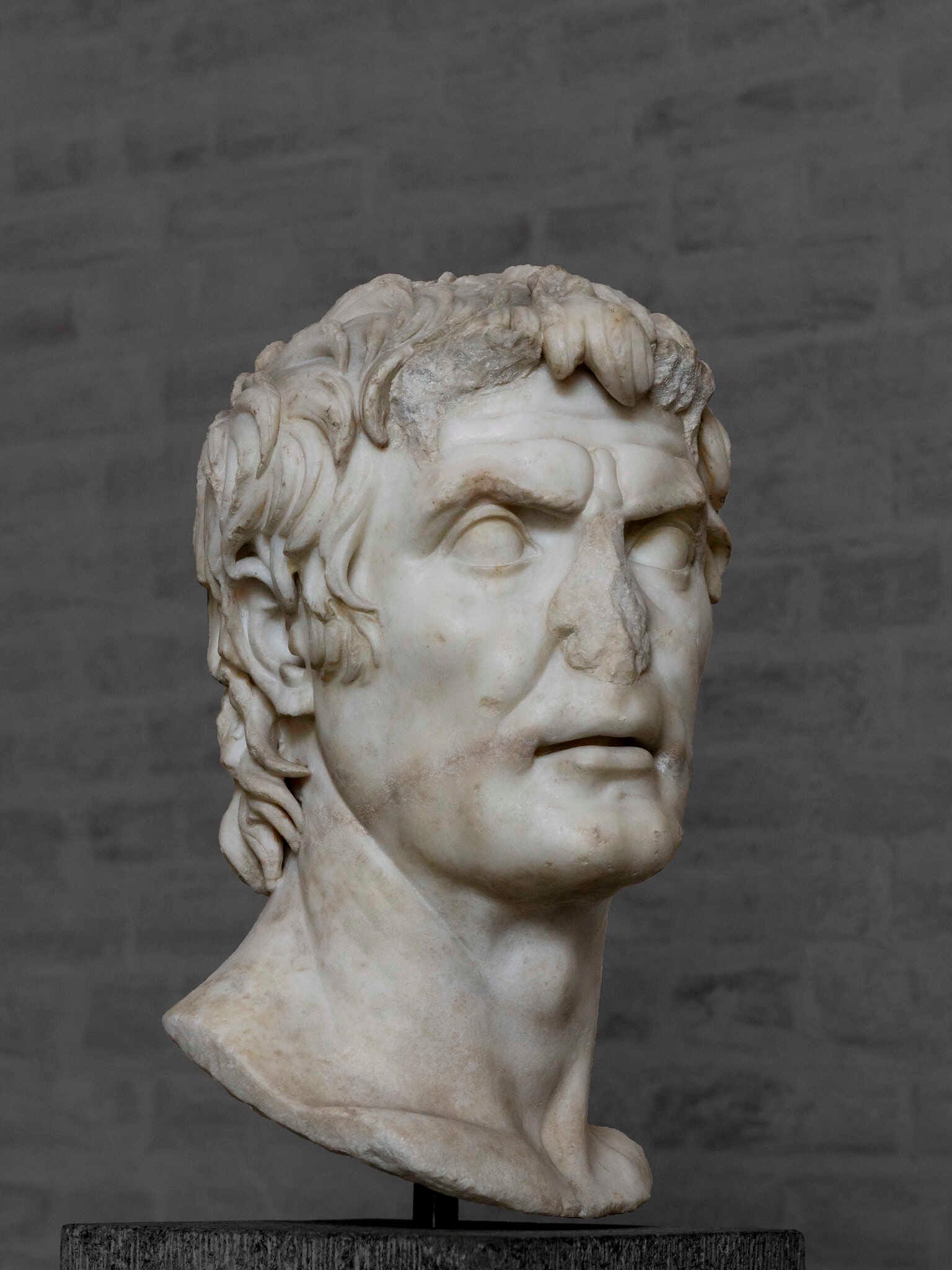

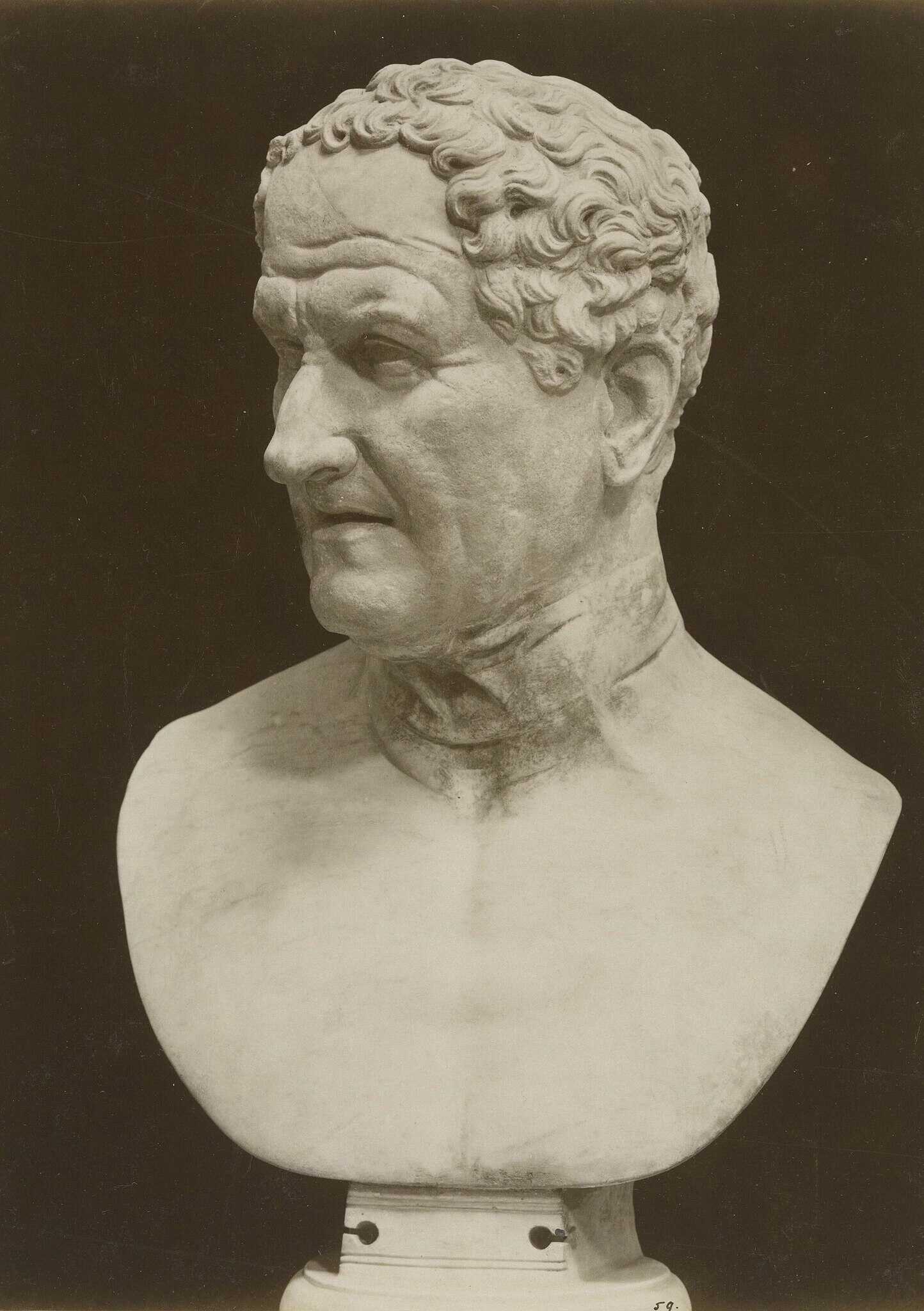

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix was the first Roman general to march on Rome at the head of his legions, the first to unleash proscriptions as a tool of political terror, and the first to hold the dictatorship without limit of time. Yet in a move that stunned his contemporaries, he later resigned his power voluntarily and retired to private life.

Sulla’s career was a paradox of brutality and order, destruction and reform. He reshaped the Republic through bloodshed and legislation, leaving a legacy that paved the way for Caesar and Augustus. To understand the collapse of Republican Rome, one must first reckon with the shadow of Sulla.

No Better Friend, No Worse Enemy

Corruption and greed were as entrenched in the Republic as in any other age, and men who genuinely put the state above their own interests were always in the minority. Sulla was one of those men, though the envy, opposition, and short-sightedness of rivals repeatedly drove him to decisions that would forever mark his name in infamy.

Yet Sulla’s devotion to Rome was sincere. Unlike those who loved her for the honors, wealth, and power she could bestow, Sulla revered Rome herself. To him, she was both mother to her citizens and mistress to be loyally served. When circumstances finally allowed, after years of struggle, he enacted legislation that blended practical common sense with reforms designed to restore prosperity after decades of war had drained Rome’s lifeblood.

Soldier and Statesman

His early career was forged in those conflicts. He fought alongside Gaius Marius against the Germanic tribes still seeking a homeland, and in the Jugurthine War it was Sulla who engineered Jugurtha’s capture. He later confronted Rome’s Italian allies, who resisted her dominance and resented their unequal treatment, in a war that dragged on for years.

During this struggle, he was awarded the Corona Graminea, the Grass Crown—the highest honor a Roman commander could receive—for saving his army outside Nola. He also subdued Pompeii, transforming it into Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum, Sulla’s colony dedicated to Venus. But despite these triumphs, the Republic was financially exhausted and politically unstable.

Sulla sought solutions but found his way blocked by rivals who cared more for their own gain than the recovery of the state. His hatred of Rome’s financiers was legendary. He despised the bankers and moneylenders who had grown exceedingly rich while the Republic teetered, yet refused to fund his campaigns in the East. They preferred to send him away, hoping to profit from new conquests, but left him to find ships, men, and supplies on his own when he turned toward Greece.

It is worth remembering that before Caesar crossed the Rubicon and later assumed the dictatorship—and before he earned the Corona Civica—Sulla had already marched on Rome and held an open-ended dictatorship, having earlier won the Corona Graminea. Unlike the temporary six-month dictatorships granted in emergencies, Sulla seized the position for as long as he thought necessary to rebuild the Republic’s foundations. His reliance on extreme measures has since overshadowed his achievements, but to him they were essential to restore order.

Foremost among his enemies was the equestrian order, whose opposition defined much of his career. By the time of his return to Rome, the Republic was collapsing, and Sulla was determined to end the self-interest of the knightly class, refill the treasury, restore temples, and revive the state. He cut down those who stood in his way, convinced they valued only their own wealth while he labored for Rome’s survival.

His constitutional reforms reflected this conviction. Critics attacked him for strengthening the Senate and weakening the tribunes, but these measures targeted real abuses. The Senate needed renewed authority to govern an expanding empire, while the tribunes’ veto power—so easily bought—paralyzed reform. By curbing these corrupt practices, Sulla cleared the way for genuine restoration.

His assault on the equestrian class was also pragmatic. They had thrived under Marius, Cinna, and Carbo, and now their fortunes financed Rome’s recovery. Their estates were confiscated, their wealth poured into the empty treasury. Unlike others who might have seized such riches for themselves, Sulla redirected the spoils to the state. Though never rich by the standards of his peers, he refused to indulge personal gain, channeling resources instead into Rome’s renewal. Caesar, in contrast, would later raid the treasury for his own ambitions.

The Dictator Who Let Go

In little more than two years, Sulla remade the Republic. Then—as already mentioned—in a move no one anticipated, he laid down his dictatorship and retired. No Roman had ever voluntarily abandoned such absolute power. Caesar could not; knowing his enemies waited to destroy him, he declared himself dictator for life and was ultimately cut down. Sulla, however, kept his word. Once his reforms were complete, he returned to private life, accompanied by those who loved him despite years of turmoil.

Sulla had begun his life with striking beauty, though in Rome such looks were as much a liability as a gift. Attractive boys were suspected of being prey to older men; handsome men were envied as rivals in love. Yet Sulla defied the stereotype. He proved himself anything but a lightweight: a soldier, a commander, and a man of immense charm who collected friends easily and kept them for life. He was no mad despot surrounded only by flatterers, but a leader with genuine loyalty from those who knew him well.

Later in life, illness marred his once-admired face. Ancient writers described his complexion as resembling “mulberries sprinkled with oatmeal,” possibly from scabies, shingles, or another untreatable condition. The pain drove him to drink, hastening his decline. Yet even then, his motto rang true:

“No better friend, no worse enemy.”

He was merciless toward those who opposed him but steadfast toward those who stood by his side. Many of his closest companions were outsiders—actors, dancers, and the poor—friends he had made in youth when he lacked money to move in aristocratic circles. They remained loyal to the end, following him into retirement.

These associations, along with his rumored affairs with both men and women, long tarnished his image among traditional historians, who painted him as immoral or decadent. Today, however, it is easier to see beyond those labels to the complex man beneath: a ruthless reformer, a charming friend, a dictator who rebuilt Rome and then relinquished absolute power.

Sulla lived in an age of turbulence, alongside some of the Republic’s most formidable figures, and left behind a legacy that was both admired and feared.

A sketch of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, with a map of the Roman Empire in the background. Credits: Andrew_Howe from Getty Images Signature, Vintage Illustrations, Composition by Roman Empire Times

Consulship, Marriage, and the First March on Rome

By 88 BCE, Sulla had climbed into Rome’s ruling elite. He sealed his social position by marrying Caecilia Metella, the widow of the Princeps Senatus, a match that cemented his standing but also forced him to divorce his previous wife. That same year, he gained the consulship and was awarded command of the lucrative eastern war against Mithridates of Pontus.

Yet politics in Rome turned against him. Marius and his allies maneuvered to strip him of command and grant it to Marius instead. Outraged, Sulla marched his loyal legions into Rome itself — the first general to do so. The city was seized in chaos, setting a precedent of military intervention in Roman politics. This act stained Sulla’s name forever, but it also ensured he retained command and set him on a collision course with Marius and his supporters.

The Eastern Campaign and the War Against Mithridates

Sulla inherited a desperate situation in the East. Mithridates VI had overrun Asia Minor, and the Romans, drained by the Social War, lacked funds and manpower. Sulla, resourceful but perpetually short of money, fought brilliantly nonetheless. He defeated Mithridates’ forces in Greece, stormed Athens after a brutal siege, and destroyed Mithridatic armies at Chaeronea and Orchomenus.

These victories not only restored Rome’s dominance in the East but also filled Sulla’s coffers with the wealth he needed for his eventual return to Italy. The campaigns hardened him: ruthless toward enemies, confident in his destiny, and certain that only strong leadership could save the Republic.

Civil War and the Battle for Rome

By 82 BCE, Rome was again in flames. Sulla returned from the East to find Marius dead but his faction still powerful under leaders like Carbo. The campaign was bitter, marked by battles across Italy. At the River Aesis, Sulla’s ally Metellus and the young Pompey won decisive victories. Later, Sulla crushed the Marian forces at the Colline Gate outside Rome in one of the bloodiest battles in Roman history.

These triumphs left Sulla master of Rome. With enemies destroyed and legions at his back, he assumed supreme power. It was in this crucible of civil war that his reputation as both savior and butcher was sealed. (Sulla: A dictator reconsidered, by Lynda Telford)

Sulla’s Dictatorship: Reform, Terror, and the Shadow of a Twisted Romulus

When Lucius Cornelius Sulla seized absolute power in Rome, he envisioned himself as more than a temporary strongman. He acted as a refounder of the Republic, a figure who would restore order through laws and institutions. His contemporaries recognized this ambition: Sallust later sneered at him as a “twisted Romulus” (scaevos iste Romulus), mocking his claim to be a second founder of Rome. The office he claimed was not the traditional, short-term dictatorship but one formally designated dictator legibus scribundis et rei publicae constituendae—a dictator empowered to make laws and “reconstitute” the state.

Sulla’s constitutional plan was coherent. By strengthening the Senate, imposing legal checks on magistrates, and curbing the influence of popular assemblies, he sought to place power firmly in the hands of what he considered the “right” class of men. In practice, this meant excluding opponents, silencing the people’s voice, and stripping away avenues for ambitious individuals to challenge the senatorial elite.

His reforms enlarged the Senate to about 450 members (with later automatic increases through quaestors), a body large enough to dilute rival cliques but still functional as a deliberative council. For Sulla, this was a way to restore stability and prevent corruption; for his enemies, it was the architecture of tyranny.

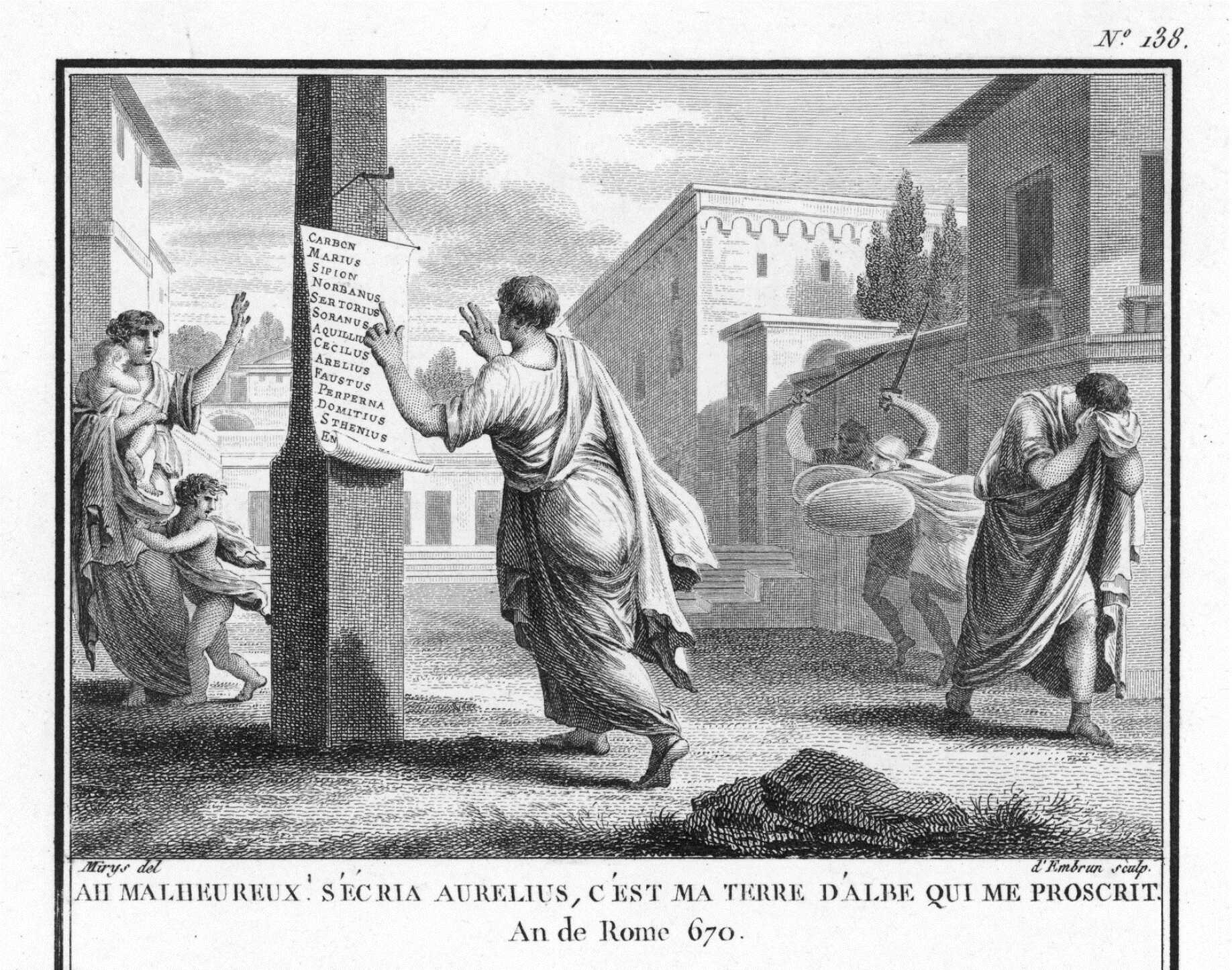

The darker side of his dictatorship was most visible in the Forum, the symbolic heart of Rome. There, Sulla ruled through fear. Proscription lists were posted in public, and the severed heads of his enemies decorated the rostra as grim trophies. Appian and Dio describe a city in terror, where each Roman weighed whether to appear in public or remain at home, knowing either choice could be fatal. The Forum became Sulla’s stage: he rebuilt the Curia, placed his equestrian statue on display, and turned the rostra into his tribunal.

From this seat he distributed rewards to loyalists, ordered forced marriages among the elite, and presided over brutal punishments. The execution of Lucretius Afella, cut down in the Forum for defying Sulla’s will, showed how arbitrary power had replaced civic freedom.

Even the most powerful men were not immune. Pompey was compelled to divorce his wife and marry Sulla’s stepdaughter Aemilia, who was herself torn from her previous husband. Caesar resisted pressure to abandon his wife and barely escaped with his life. Whether or not every story is fully reliable, their survival in ancient accounts proves the climate of intimidation was real. Romans remembered this era as one where Sulla’s physical presence in the Forum meant domination, fear, and the bending of private lives to his will.

By 81 BCE, Sulla stepped down from the dictatorship, passing into the consulship of 80 with Metellus Pius as colleague. He presented this as a return to normality, even boasting of the harmony between himself and Metellus as proof of his lifelong felicitas, or good fortune. But to contemporaries, this “normality” felt hollow.

Cicero’s speech Pro Roscio Amerino, delivered during this year, illustrates the tension: it outwardly avoided direct attacks on Sulla, but its hints and silences evoked the unsayable truths everyone knew. Romans lived in uncertainty, unsure whether Sulla would behave as a statesman or a tyrant.

His settlement, moreover, did not outlast him. After Sulla’s death in 78 BCE, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus openly challenged his system. Lepidus courted the urban plebs, proposed recalling exiles and undoing Sulla’s confiscations, and even threatened to march on Rome. Though ultimately defeated, his revolt revealed how unstable Sulla’s reforms had been. Later generations—Pompey, Crassus, and above all Caesar—would overturn or bypass his institutions.

Sulla’s dictatorship, then, left behind a paradox. On the one hand, he crafted a vision of order and law, binding Rome’s governance to the authority of the Senate. On the other, he ruled through terror, exclusion, and violence, imprinting on Rome the lesson that brute force and political murder could dictate constitutional change. His contemporaries remembered the severed heads, the forced marriages, and the auctions of the proscribed. His enemies called him a tyrant, his supporters a restorer of the Republic. History remembers both.

The Uncertainty of 80 BCE

Between Sulla’s decisive victory at the Colline Gate in 82 BCE and the end of his consulship in 80, just over two years passed in which his position evolved in ways difficult to define. Official markers—the end of the proscriptions, his assumption of the consulship with Metellus Pius—suggested transitions, yet ancient sources were more fascinated by the drama of his final abdication than by the gradual stages of his power. For Romans, what mattered was not the technical shift from dictator to consul, but the astonishing fact that Sulla eventually laid down supreme authority and returned to private life.

Plutarch and Appian, our most detailed sources, blur the lines between dictatorship and consulship. Plutarch depicts Sulla as equally tyrannical in both roles, collapsing distinctions to emphasize his illegitimacy as a ruler. Appian, meanwhile, presents Sulla’s consulship of 80 as a façade of republican government, assumed to maintain appearances while he continued to rule by fear. Neither author dwells on the nuances of 80 BCE itself, and both are colored by later experiences of autocracy. Their accounts remind us that even in antiquity, the precise contours of Sulla’s power during this year were difficult to grasp.

"[Sulla] … remained in arms for ten years together, making himself now consul, and now dictator, but always being an usurper."

Plutarch, Lysander and Sulla, section 2.1

Plutarch portrays Sulla as shifting between consul and dictator — but always remaining an usurper.

“Sulla made himself consul for the following year, in order that he might appear to be quitting the dictatorship voluntarily.”

Appian Civil Wars 1.103

Appian meanwhile, presents Sulla’s consulship of 80 as a façade of republican government, assumed to maintain appearances while he continued to rule by fear.

As aforementioned, Cicero’s Pro Roscio Amerino, delivered in 80 BCE in defense of Sextus Roscius against a charge of parricide, provides our sharpest window into this elusive period. The speech, one of Cicero’s earliest, now dominates modern understanding of the year. Yet it also reflects the uncertainty of its own time.

Romans were unsure whether Sulla’s authority was softening into something like constitutional normality, or whether tyranny still ruled unchecked. The atmosphere was one of fear and guesswork: no one knew what behavior Sulla might tolerate, or how he would respond to defiance. Figures like Pompey, who dared to show independence, became focal points of fascination. In this environment, Cicero’s words had to tread carefully—his oratory gestured toward the unsaid as much as to what could safely be spoken.

The year 80 BCE thus remains shadowed in ambiguity. It was neither a clear end to dictatorship nor a true return to republican government, but an interlude defined by uncertainty, when Rome lived under a ruler whose intentions and limits no one could confidently predict.

The Forum of Fear

Sulla’s authority after the Colline Gate was maintained less by loyalty than by terror. The proscriptions, the massacre of thousands of war captives in the Campus Martius, the execution of Lucretius Afella in the Forum, and Sulla’s own speeches demanding obedience created an atmosphere where defiance seemed unthinkable. Ancient writers like Dio and Appian describe a forum silenced by fear. Yet even as Sulla stepped back from the dictatorship into the consulship at the end of 81 BCE, his presence still dominated Rome.

Military unrest lingered. In Italy, cities like Nola and Volaterrae continued to resist, harboring proscribed men until they were expelled and killed. These deaths showed that the trauma of the proscriptions extended beyond the closing of the lists in 81 BCE; the stigma of being proscribed was still lethal. Abroad, Rome’s attention turned to Spain, where Sertorius emerged as a formidable opponent after defeating Roman governors. The Republic, though outwardly restored, was still unsettled.

In this tense climate, ordinary politics resumed, but with unease. Routine senatorial decrees and building projects, such as the restoration of the Capitol and the Curia, gave an impression of stability, yet they were also visible reminders of Sulla’s supremacy. Even elections betrayed the ambiguity of the moment.

When the people elected Sulla consul again for 79 BCE, he declined, but the gesture revealed that Romans themselves did not know whether his rule was meant to end. Fear drove them to demonstrate loyalty, unsure of the consequences of not doing so.

This uncertainty bred fascination with those who dared to resist. Pompey secured a triumph despite Sulla’s reluctance, and stories circulated of his bold remark that more men worship the rising sun than the setting one. Others, like Lentulus Sura, defied Sulla in the Senate and lived to tell the tale, though the risk gave their actions a notoriety of their own. Romans were captivated by these moments, not because they changed policy, but because they tested the limits of what Sulla might tolerate.

At the heart of this atmosphere was Sulla’s reputation for unpredictability. He could order the massacre of thousands without warning, yet spare offenders of greater crimes. This volatility was the very essence of tyranny as described in Greek and Roman thought, and it magnified the fear that governed Roman life in 80 BCE. The senators’ chilling experience of hearing the screams of slaughter outside the Temple of Bellona during one of their meetings epitomized this uncertainty: they knew something horrific was happening, but not what.

The year 80 BCE was thus marked less by formal offices than by the psychology of fear. Romans lived in a haze of uncertainty, never sure what words or actions might cost them their lives. It was in this context of terror and ambiguity that Cicero delivered his Pro Roscio Amerino, a speech that tested how far one could speak in Sulla’s Rome—and hinted at the unspeakable realities that everyone knew but few dared to voice. (Rome after Sulla, by J. Alison Rosenblitt)

Sulla’s Image, Abdication, and the Fragile Legacy of His Republic

Sulla was not only a general and dictator—he was also his own historian. In his lost Autobiography, he worked hard to shape how posterity would remember him. He presented himself as a man of felicitas (good fortune), chosen by the gods to save the Republic. His narrative emphasized victories, reforms, and his voluntary abdication, casting his dictatorship as a noble restoration rather than a reign of terror.

This self-fashioning, however, contrasted sharply with how contemporaries and later historians remembered him: as the butcher of the proscriptions and the tyrant who ruled Rome through fear. His abdication remains one of the most debated aspects of his career. Officially, he stepped down from the dictatorship around the end of 81 BCE and assumed the consulship of 80 with Metellus Pius.

Ancient writers, however, rarely distinguish between dictatorship and consulship in these years. Modern scholars argue that contemporaries themselves were uncertain—what mattered was not the technical office Sulla held, but the extraordinary reality of his power and the shock when he finally returned to private life.

Yet even in retirement, the structures he created proved brittle. The reforms that were meant to stabilize the Republic—strengthening the Senate, curbing the tribunes, restraining individual ambition—collapsed almost immediately after his death in 78 BCE. Marcus Aemilius Lepidus openly challenged the Sullan order, rallying the urban plebs and promising to restore property to the dispossessed.

Though his revolt was crushed, it revealed how shallow the foundations of Sulla’s settlement were. Within a generation, Pompey and Caesar would draw upon his example, marching armies into Rome and surpassing the precedents he had set. In the end, Sulla’s attempt to control his legacy failed.

He wished to be remembered as a founder, a new Romulus, the man who restored Rome’s greatness. Instead, he was recalled as a tyrant whose terror scarred Roman memory and whose constitution disintegrated with startling speed. His autobiography vanished, but the severed heads on the rostra and the proscriptions remained engraved in Rome’s collective consciousness.

Sulla’s life and career remain a paradox. He was the first Roman to march on Rome, the first to use mass terror as a tool of politics, and yet the only dictator to lay down absolute power voluntarily. He claimed to have restored the Republic, but in truth he taught Romans that constitutions could be bent by violence and that armies could decide politics. His reforms collapsed almost as soon as he died, but the example he set endured. In Sulla’s shadow, Caesar, Pompey, and the emperors who followed learned that power seized by the sword could never again be returned unchanged.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: