The Insulae: The Apartment Buildings of Ancient Romans

The insulae of the Roman Empire are a fascinating reflection of Roman architectural innovation and urban planning.

Insulae were large multi-story apartment buildings in ancient Roman cities, particularly in Rome itself. They housed the majority of the urban population, including middle- and lower-class citizens, artisans, and sometimes wealthier individuals, though those of higher status often lived on the lower floors.

Rome’s Main Housing Structure

The distinction between domus (townhouse) and insula as terms for private residential property in Rome dates back to authors like Tacitus and Suetonius and persisted into the fourth century. However, the meaning of insula is not always clear. While it literally means "island," in the context of urban housing, insula could refer to anything from a city block to a multi-occupancy residential building owned by one person, or even a single unit within a larger structure.

One key difference is that insula generally referred to rental properties, whereas domus was more likely owner-occupied. Multi-story apartment blocks, common in Rome, were primarily rental properties, with some owners occupying parts of the building. These structures were often owned by wealthy individuals, including senators, and were a significant source of income, though risks like fire and collapse made them precarious investments.

Insulae were common in Rome due to the city's large population, with multi-story buildings designed to maximize housing space.

Model of a Roman insula apartment building. Credits: Hiro-o, CC BY-SA 1.0

Augustus and later Trajan imposed height restrictions on buildings, but some insulae exceeded these limits. Archaeological evidence from Rome is limited, but some remains, such as those on the Capitoline Hill, suggest that insulae could reach significant heights and had diverse designs to accommodate a variety of residents, including shops on the ground floor.

Evidence from nearby Ostia complements the sparse data from Rome, showing that some of those building included high-status apartments alongside more modest dwellings. Insulae housed the vast majority of the Roman population, with over 40,000 recorded in official documents, compared to fewer than 2,000 domus.

While these buildings varied in size and layout, they were crucial in accommodating Rome's diverse urban population, providing housing for both the wealthy and lower classes in a range of living conditions. (A companion to the city of Rome, edited by Claire Holleran & Amanda Claridge)

What were the Insulae?

The term insula, when used by the Romans in the context of urban architecture, originates from the word meaning "island," but its application to residential settings is not immediately obvious. In architectural and residential contexts, the term is ambiguous.

While it has often been translated as "apartment house" or "apartment block," the original sources suggest meanings more closely aligned with "street block" or "city block." Over several centuries, from the 1st century B.C. to the 4th century A.D., insula developed two primary meanings. The first refers to a city block as a whole, including all the structures within it, and the second refers to individual private property units that were distinct and lockable within the city block.

If insula did mean "apartment house" in some cases, this was likely just a subset of both meanings, as apartment houses were distinct properties within a block and often occupied large portions of the block, particularly as seen in examples from Ostia. Both of these meanings are consistent with the term’s original sense of "island."

Whether referring to a street block, apartment house, or independent unit within a block, the term doesn't offer much insight into the behavior or functions within those spaces. Instead, its significance is largely legal, focused on how properties were defined, with the term covering a range of unit sizes rather than the activities conducted within them.

Several studies have tried to clarify the relationship between the term insula and its potential archaeological counterparts. To begin, dictionaries define insula as "a large building, let out in separate dwellings, a tenement house, block of flats." Another dictionary supports this, grouping insula under the heading aedes conducitiae (buildings for rent).

However, the meaning of insula is not as clear-cut as these definitions suggest. Glenn R. Storey in his work, "The Meaning of "Insula" in Roman Residential Terminology," argues that the term has four primary categories of architectural correlates in Roman antiquity, though its usage is often ambiguous, making it unclear which category applies in any given case.

Most uses are subsets of insula as a street block, while others expand the basic idea of a structural entity surrounded by free space. As Roman urban structures became more complex, the term insula gained legal significance, denoting a private property unit separate from others, while retaining its original meaning of a large freestanding structure.

Credits: ZDF/Terra X/Story House Productions/Jens Afflerbach, Sebastian Scherrer/Jürgen Rehberg/Franziska Menz/Eike Wichmann, Fritz Göran Vöpel, Jörg Barton, Martin Wolkinger, Roger Grein, CC BY 4.0

The Four Categories are:

- Insula as a street block, defined by the concept of ambitus (a walking space that isolates a structure), dating back to the Twelve Tables.

- Insula as a freestanding building, separated on all four sides, though it's unclear whether this refers to an entire city block or just a part of it. This is the favored interpretation in dictionaries, but I argue these cases may actually belong to the first category.

- Insula as an independent unit within a larger structure, as seen in the fourth-century Regionary Catalogues. This meaning includes the taberna/coenaculum combination (a shopfront with or without an attached apartment) or simply a coenaculum (apartment), referring to a rental unit distinct from a domus.

- Insula as a funerary structure, the rarest category, related to funerary material on taberna structures.

Surprisingly, almost none of the examples cited can be clearly matched with any one of these categories.

The Street Block

Vitruvius, in his De Architectura says:

"For this reason [to keep winds from rushing through the streets] the orientations of main streets must be turned away from the sources of the winds, in order that gusts be deflected, broken, and dispersed when striking the insulae on the corner."

If insulae were translated as "buildings" in this passage, it would align with the common interpretation of insula as a separate structure, like an apartment house. However, Vitruvius is discussing town planning and suggests that city blocks should be arranged to break up winds.

Since Roman town planning involved the layout of rectangular city blocks, it's more likely that insulae in this context refers to city blocks rather than individual buildings. While it's true that blocks, as lines marked by Roman surveyors, wouldn't physically block the wind—it's the buildings within them that would—the interpretation of insulae as city blocks is preferable.

This is because Vitruvius' advice requires streets to follow a unified orientation, and in town planning, the layout of streets and blocks happens before the placement and construction of individual buildings, such as apartment houses, within those blocks.

The next passage clarifies the idea of insula as an architectural entity by outlining the reasons the word, meaning "island," could be applied in this context. Paulus in Festus, in De Significatu Verborum, states:

"Insulae properly defined are entities not joined by party walls with neighboring entities, and are surrounded by a public or private pathway.

They are so called by clear analogy with those landmasses that are at the confluence of rivers and the sea, and are found in the open ocean."

The key phrase here is "public or private pathway," implying that the structure's isolation, like that of an island, must occur on a relatively large scale. A public pathway, such as a street, would satisfy this condition, making an architectural mass surrounded by streets equivalent to a city block.

The Ambitus

Passages from Varro and Paulus in Festus introduce the concept of ambitus, the space left around a structure, which seems to refer to the "public or private pathway". This concept dates back to the time of the Twelve Tables, and the standard width of the ambitus, two and a half Roman feet (about 70 cm), reflects an ancient tradition.

In De Lingua Latina, Varro explains, "Access is a path worn by pedestrians walking around; for access is a circuit; from this fact, interpreters of the Twelve Tables describe the 'access of the wall' as a circuit." Similarly, Paulus in Festus, in De Significatu Verborum, defines "access" as "the space between buildings in a neighborhood, measuring two and a half Roman feet, to facilitate passage."

Although insula is not explicitly mentioned, Paulus in Festus describes the ambitus as being "between the buildings of a neighborhood." Since references to insulae come primarily from the city of Rome, where the streets went up the city's hills, it is reasonable to infer that city blocks were defined by major thoroughfares, with the subdivision below a vicus or vicinum likely being a city block.

These blocks would be outlined by streets, though the words for streets in the passages seem to refer to major roads rather than smaller ones. The ambitus, measuring just 70 cm, was probably enough space for a "person to walk straight through without turning their shoulders, and thus defined an independent architectural unit, or "island" (insula).

Although the ambitus is small and resembles an alleyway, it must be understood as a minimum space requirement meant to allow for walking around an architectural mass.

Casa di Diana Ostain insula, reconstructed by Italo Gismondi, CC BY-SA 3.0, Upscaled by Canva

Larger streets may have been loosely included under this term, as Roman terminology suggests broad boulevards but lacks a specific term for streets between narrow alleyways and major thoroughfares. In some cities, like Pompeii and Ostia, small pathways similar to the legal size of the ambitus weave through city blocks, though they do not usually encircle entire buildings, so they do not technically qualify as angiportus.

"Certainly if panels made from it [larch wood] were to be connected to the eaves running around the insulae, the buildings would be freed from the danger of fires crossing over to them."

Vitruvius, De Architectura

This passage offers a solid explanation of why Roman urban planning was so focused on creating insulae, or "islands" of structural configurations. The main reason was likely the perceived danger of fires rapidly spreading between buildings in the crowded urban environment. This is why the ambitus, the intervening space between buildings, was considered so important.

However, even with fire-resistant wood, a gap of just two and a half Roman feet (70 cm) wouldn't have been very effective at stopping fires. If, instead, the insula referred to a city block surrounded by streets several meters wide, such a gap would significantly reduce the risk of fire. Vitruvius's recommendation to use larch wood across entire city block fronts, rather than just on individual apartment houses, would thus carry more weight.

The Foundation of Roman Urbanism

Roman towns were organized into local units known as vici, which initially referred to rows of houses along a street but later came to describe entire quarters, including main streets, alleys, paths, and passageways between buildings. These vici were some of the oldest and most significant units in Roman urban life and were semi-independent, sometimes even walled off from others. The vici also had their own local cults and officials responsible for overseeing the community, a tradition dating back to the time of King Servius Tullius, who divided the city into four tribes and established sanctuaries at crossroads.

After the great fire during Nero’s reign, Roman town planning underwent significant reforms, with streets widened, house heights regulated, and open spaces introduced between buildings. This rectified the irregularity of older vici and helped create a more organized urban layout. Apartment buildings, or insulae, were protected by porticoes built along the street fronts, funded by the emperor.

Additionally, local officials were tasked with knowing where each inhabitant lived, a practice possibly connected to Augustan reforms. Although some of this information is rooted in ancient traditions, there is evidence that Augustus reformed local religious cults, such as the Lares compitales, by adding the worship of his own genius to these rites. These urban planning structures and local governance practices reveal the deep connection between Roman town organization and both religious and administrative control. (Vici and Insulae: the homes and addresses of the Romans, by Paavo Castren)

Architectural Design and Structure

Reconstructing the character of residential life in ancient Rome involves integrating multiple sources of evidence: archaeological findings from cities like Ostia and the Vesuvian cities, the Severan Marble Plan from the early third century A.D., and the rich written records, including literary and documentary sources such as inscriptions and legal texts.

Additionally, "quasi-administrative" documents like the Regionary Catalogues contribute valuable information. These written sources must be interpreted alongside archaeological data, especially in terms of residential terminology. In a previous synthesis, the concept of the "architectural/residential unit" (ARU) was introduced as the basic building block of urban life, representing a self-enclosed unit where a household could have lived. Recent studies suggest that the ARU was fundamental to the urban structure of Roman cities, with each unit typically housing one household.

In the American journal of archaeology, Glenn R. Storey, in his article "Regionaries-Type Insulae 2: Architectural/Residential Units at Rome", addresses the meaning of the term insula in the fourth-century Regionaries (Curiosum and Notitia), which list urban features of ancient Rome.

He explores two interpretations: insula as a freestanding building (alternative A) or as an isolated residential unit within a building, such as an apartment (alternative B). Based on studies from Ostia, Storey supports alternative B, suggesting insula refers to smaller subdivisions within a block rather than standalone buildings.

Storey argues that Roman street blocks were likely complex, containing a mix of large and small structures, unlike the more organized row houses of later periods. He believes that administrative language later used the term insula to describe both street blocks and their subdivisions.

The Regionaries, or Regionary Catalogues, are two ancient Roman documents that list landmarks and urban features organized by the 14 regions of Rome established by Augustus. These documents, likely compiled during the fourth century A.D. under Constantine, possibly for administrative purposes, contain information collected during the reign of Diocletian or earlier.

Although a lot of speculation exists on the matter, the definite purpose of the Regionaries remains unclear.

Insula 1, in Region V, Pompeii. Credits: Pompeiana79, CC BY-SA 2.0, Canva

They may have been used by the Urban Prefect, a high-ranking official acting as a "vice emperor," to manage inhabitants, fire control, policing, and administrative tasks like food distribution. Alternatively, the documents might have been related to tax collection, as Roman residences were taxed at around the same time.

Although the Regionaries might resemble a guide to the city, they lack the detail and organization needed for such a purpose, suggesting they were more aligned with the periegesis tradition—a literary genre focused on topography and historical landmarks.

Similar documents existed for cities like Constantinople and Alexandria, often distinguishing between private houses (domus) and rental properties (insulae). The ratio of domus to insulae in the Roman documents is notably low compared to other cities like Alexandria and Constantinople, where the proportion of domus to multi-unit properties was smaller.

Insula IV ii

Insula IV ii, located on the southern cardo maximus near the Porta Laurentina but within the Late Republican city walls of Ostia, enjoyed a strategic position close to both the city center and the city gate, which connected it to the areas beyond Ostia. Situated at the intersection of the cardo and Via della Caupona, the insula was well integrated into the urban street network. To the east, it bordered the Campo della Magna Mater, a major sanctuary dedicated to the goddess Cybele.

The insula covered an area of 7,321 m² and contained 14 buildings with various uses, including commercial spaces (shops and storage), industrial areas (workshops and production), recreational spaces (baths and inns), sacred areas (a mithraeum), communal spaces (courtyards and porticoes), and residential units on both the ground and upper floors. These spaces were functionally and spatially connected through shared courtyards.

Commercial spaces were primarily located along the street fronts, maximizing interaction with public space, while industrial areas were set deeper into the insula. The southernmost corner, the least accessible area, housed the Mitreo degli animali, a cult room for the worship of Mithras. Residential units were found on the ground floor, with the majority of living spaces on the upper levels.

The diversity of land use within the insula allowed residents to conduct most daily activities within its boundaries, while the spacious courtyards, covering about 20% of the total area, provided communal spaces for various activities to take place simultaneously. (Spatial analysis and social spaces: Interdisciplinary approaches to the interpretation of prehistoric and historic built environments, by Undine Lieberwirth & Silvia Polla)

Constructed primarily from concrete (opus caementicium), the Roman insulae were early examples of high-rise apartment living, a concept that would not reappear until the Industrial Revolution. These structures could reach up to 10 or more stories, though the upper floors were less desirable due to safety concerns and were therefore cheaper to rent. The design of insulae varied from simple two to four-room apartments for the lower classes to luxurious accommodations for the wealthier citizens, featuring large glazed windows, gardens, courtyards, and sometimes even amenities like kitchens and piped water.

Glenn Storey (professor at the university of Iowa) interpreted these figures to suggest a total of over 45,000 standalone buildings in Rome at that time. James Packer (professor of classics at the Northwestern University) contributed to the discussion by suggesting that "insula" could refer to either a singular high-rise building or a segment of a larger edifice, emphasizing the complexity of Roman urban planning and the diverse interpretations of architectural terminology.

In addition to Rome, the insulae found in Ostia Antica offer valuable insights into the architecture of these apartment complexes during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, showcasing instances of more opulent insulae. These luxury insulae typically featured a central rectangular space known as a medianum, serving as the hub for access to other areas within the apartment. The layout included varying-sized reception rooms, sometimes divided into two spaces or left as a singular large room, and were often illuminated by sizable glazed windows overlooking gardens, courtyards, or streets.

The presence of cubicula, generally two, was common alongside amenities like kitchens, latrines, and piped water on the upper floors, indicating a level of affluence. Decorative elements such as ornate pilasters or columns around the exterior doorways further suggest these insulae catered to the wealthier populace on a more permanent basis.

Conversely, Ostia also contained simpler insulae with two to four rooms catering to the lower-class residents. An example is the Casa Di Diana, where the ground floor featured a narrow corridor leading to dimly lit cells and presumably a communal living area.

Such designs, also observed at Rome's Capitoline Hill, hint at a widespread architectural response to the high demand for housing.

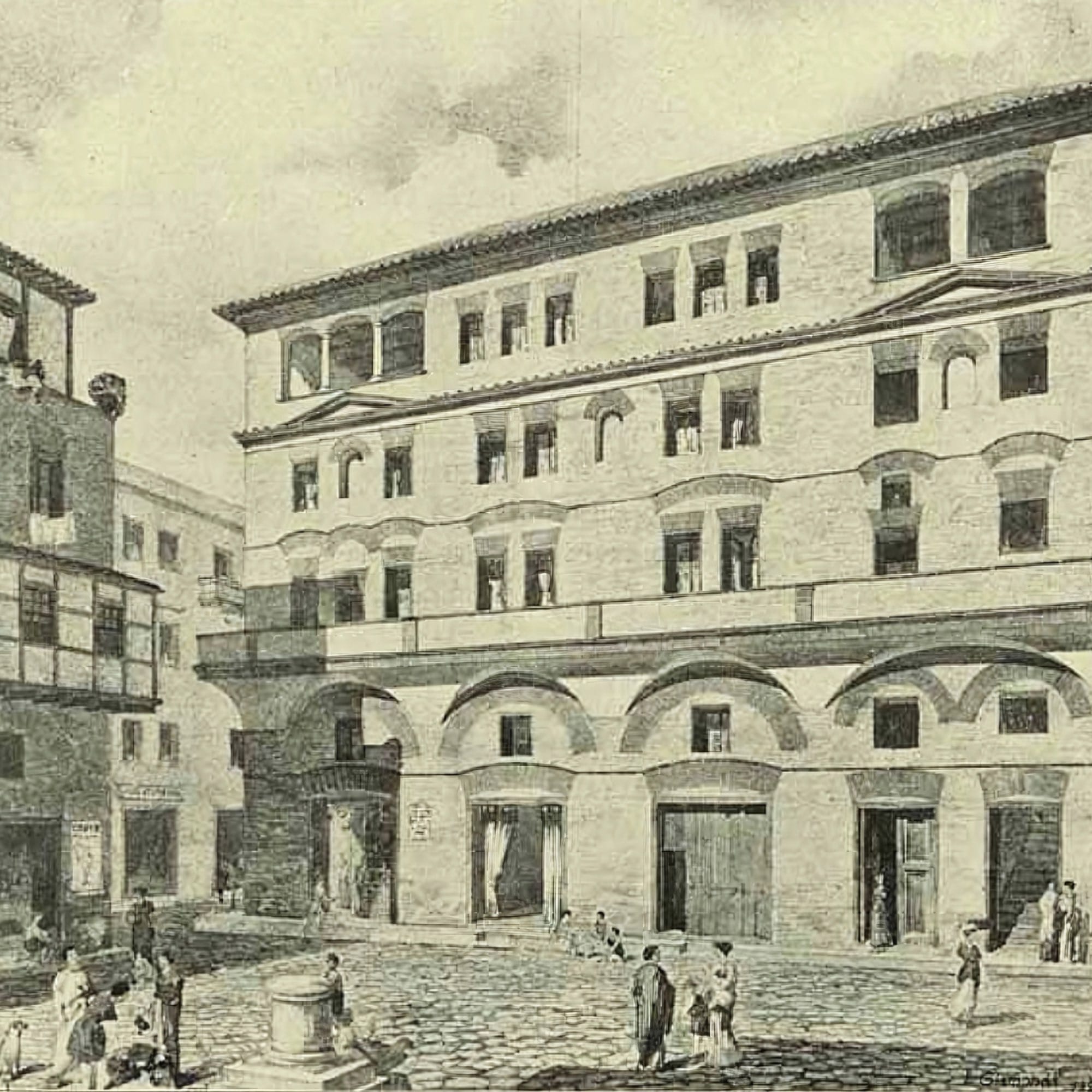

The interior of an insula in Rome near Trevi. Credits: Anthony Majanlahti, CC BY 2.0

Shared facilities like latrines and cisterns for drinking water were common among these less affluent quarters, often serving not only long-term residents but also providing temporary lodging for transient workers. Despite the lack of concrete evidence on the specifics of sharing these spaces, it's speculated that such arrangements were a necessity for the lower classes in ancient Roman society.

Living in an Insula: Pros and Cons

Living in an insula came with its unique set of advantages and challenges. On the one hand, these apartment blocks provided housing close to the city center, allowing easy access to public amenities, work, and markets. On the other hand, they were prone to fires and structural collapses, posing significant risks to inhabitants. To mitigate these dangers, Roman emperors such as Augustus and Nero imposed height restrictions and encouraged safer building practices.

The dangers of fire and structural failure prompted regulatory reforms aimed at improving the safety of insulae. Augustus, for instance, restricted the height of insulae to 70 Roman feet, a limit that was further reduced by subsequent emperors in response to catastrophic events like the Great Fire of Rome.

Strabo mentions that, similar to domus, insulae were equipped with water supply and sewage systems. However, these residential buildings were often hastily constructed with the aim of maximizing profits, leading to substandard quality. Constructed from materials like timber, brick, and eventually Roman concrete, these structures were vulnerable to fires and structural failures, a point highlighted by the satirist Juvenal.

Marcus Licinius Crassus, known for his ventures in real estate, owned several insulae in Rome. Cicero is famously quoted as expressing relief when one of Crassus' poorly constructed buildings collapsed, as it presented an opportunity to levy higher rents on a newly constructed replacement.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: