Incense in Ancient Rome: Smoke, Ritual, and Power

From temple rites to family altars and funerals, incense in the Roman Empire was a ritual tool with global supply chains, moral debates, and political weight.

Incense was not a marginal custom but a routine element of Roman religious life. Latin authors treat the offering of tura (frankincense) as ordinary in sacrifices and festivals: Ovid’s calendar of rites in Fasti has worshippers placing “grain, salt, and incense” on the fire, while Livy’s annalistic scenes of sacrifice presume aromatic smoke rising with vows and thanksgivings.

Pliny the Elder devoted long chapters of Natural History to frankincense and myrrh, tracing their Arabian sources and lamenting Rome’s appetite for expensive imported aromatics. Theophrastus’ account On Plants of the harvest of incense and myrrh and the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea’s notes on Red Sea trade reveal the network that fed Roman demand.

Roman Empire Incense: How, Where, and Why the Romans Burned Fragrance

The question, then, is not whether incense ancient Rome used existed—it did—but how Romans used it across settings, why they valued it, and what its supply meant for the Empire. Terminology mattered. Romans used tus (frankincense) and thus (incense generally) for the fragrant resins burned on coals; Greek writers speak of thymiama.

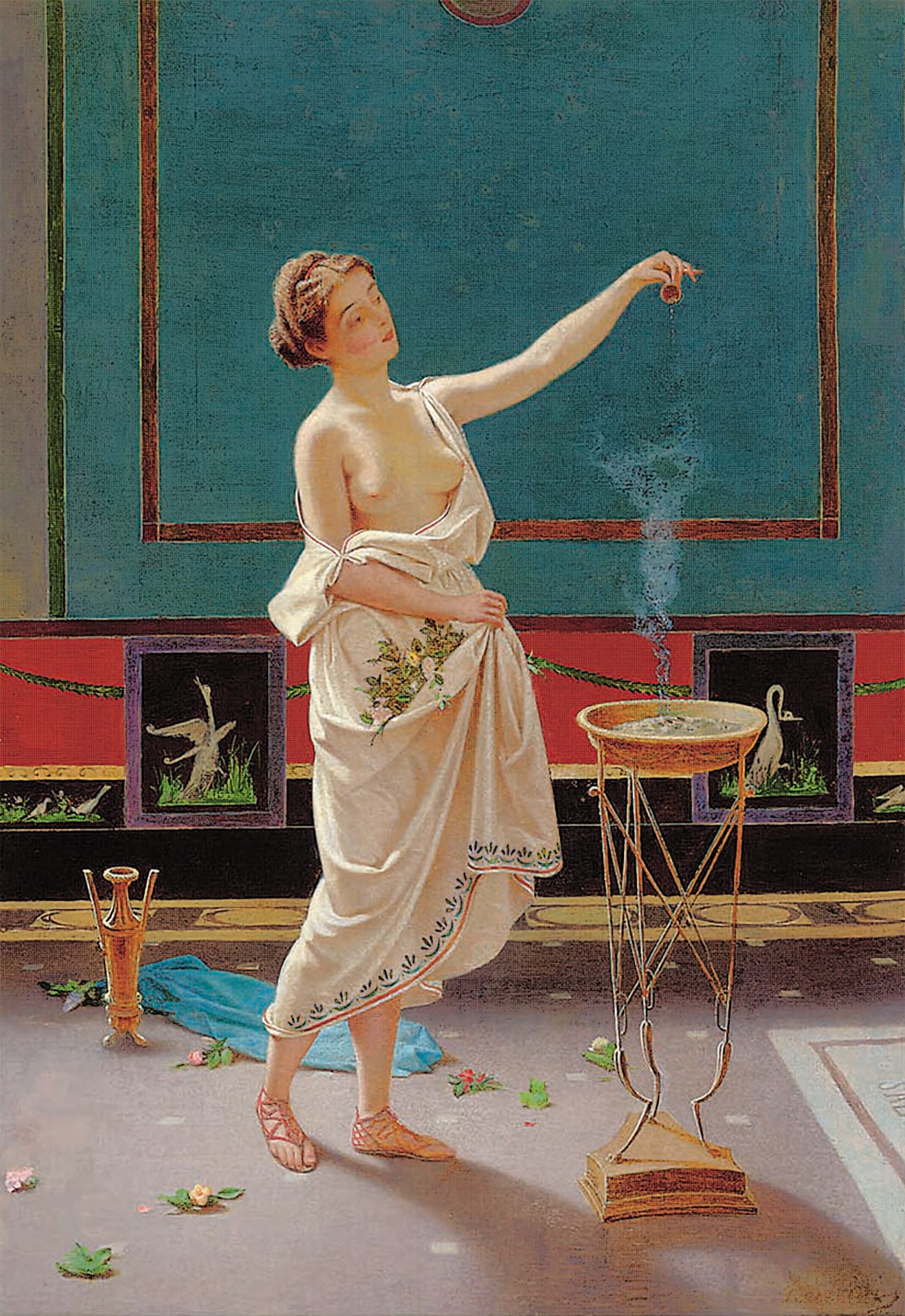

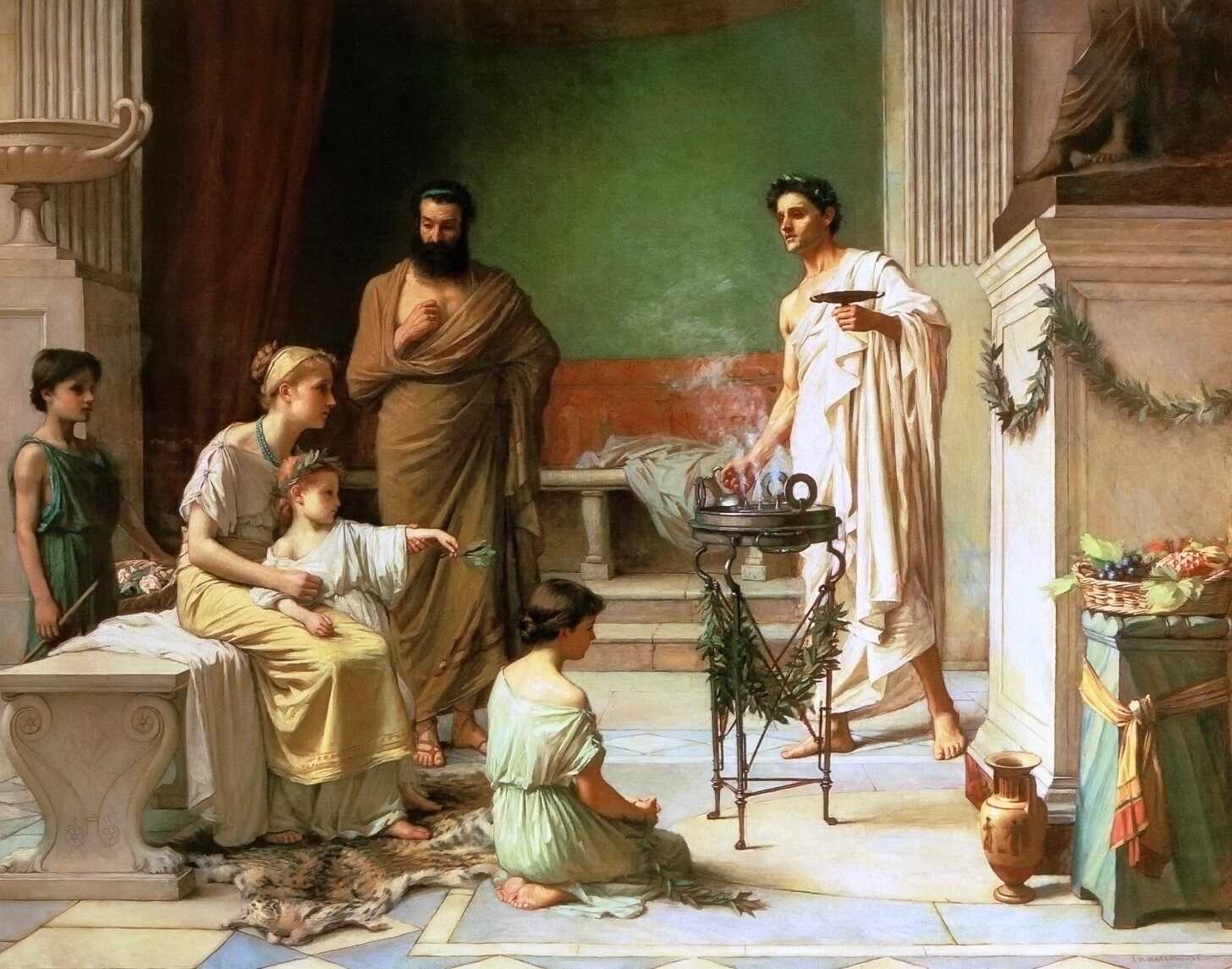

The implement was the turibulum (a censer/brazier), and the small box of resins the acerra. To “offer incense” was not an ornament added to sacrifice but part of what made the action a sacrifice. In the Roman Empire, incense marked sacred time, purified space, and gave visible form to invisible intention: the thin blue column of smoke was the rite’s signature.

Origins and Trade: Aromatics for an Empire

Roman incense was chiefly frankincense (olibanum) from Boswellia and myrrh from Commiphora—resins tapped in South Arabia and the Horn of Africa. Pliny in Natural History summarizes a system in which groves were guarded, resin tapped seasonally, graded, taxed, and funneled north through caravan routes to Mediterranean ports.

Theophrastus describes the technique of incisions and gatherings; the Periplus details anchorages and brokers along the Red Sea. By the Principate, monsoon-sailing opened a sea highway from Indian Ocean coasts to Egypt’s Red Sea ports; from there, cargos crossed to the Nile and out to Rome.

Pliny complains that “India, China, and Arabia” drained Roman silver each year, and the Muziris papyrus later confirms the staggering value of single aromatic shipments. In Roman vocabulary, tus and thus became routine liturgical items; the costly grades signaled status even as their smoke marked the act as ritually correct.

Ancient descriptions of the producing zones are surprisingly precise. As we said, Theophrastus places frankincense-groves in Arabia; later writers and modern fieldwork locate prime production in Dhofar’s coastal belt and lower mountain slopes, where trees were scored and exudate collected in seasonal rounds.

Resin was warehoused and shipped in winter. South Arabian polities controlled routes and exacted duties; middlemen protected knowledge of groves and grades, which helps explain contradictions in classical descriptions. To a Roman buyer the labels mattered—origin, color, size of tears—and the best lots commanded prices that made Roman Empire incense a small but lucrative sliver of the eastern trade.

Debate over whether such imports were “luxury” or “necessity” already ran in antiquity. Pliny’s moralizing implies useless extravagance; yet civic religion required incense at festivals, and households used small pinches regularly. In other words, context determined value.

In a city dedicating vows for victory, incense was not optional; in a private banquet, excess could be mocked. That flexibility helps explain how incense functioned simultaneously as staple of ritual and symbol of wealth. (Frankincense and Myrrh in Ancient South Arabia, by Gus W. van Beek; The Reception and Consumption of Eastern Goods in Roman Society, by Matthew Adam Cobb)

Incense at the Altar: Civic and State Cults

In public cult, incense framed communication with the gods. Priests cast tura onto the flames with prayers and mola salsa; Ovid’s Fasti sequences incense with other pure offerings. Horace in Odes imagines Lares honored with “garlands and frankincense”, and temple calendars stipulate incense at anniversaries and vows. Incense marked presence and purity: its fragrant smoke carried petitions upward and delineated sacred time from ordinary time.

A sacrifice without incense would have looked—and smelled—unfinished.

Closeup of the thymiaterion in the form of a Comic Actor. Public domain

As the imperial cult spread, incense before imperial images acquired a new weight. To burn a few grains of frankincense before the altar of Roma et Augustus expressed civic loyalty in a instantly legible gesture. The act was deliberately simple: anyone could approach, take a pinch, and cast it on the coals. Provincial inscriptions advertising priesthoods and festivals record this choreography of allegiance; the smell of incense thus became, in political contexts, the smell of consent.

Roman religious time was scented. On public holidays the city’s processions—victory celebrations, temple anniversaries, imperial birthdays—moved through streets hazed with aromatic smoke, while fixed cult sites maintained their own olfactory signatures. Such sensory consistency mattered: it taught citizens how a rite should look, sound, and smell, and it gave Roman religion one of its most memorable atmospheres. (The Worship of the Roman Emperors, by Henry Fairfield Burton; Imperial Cult and Native Tradition in Roman North Africa, by J. B. Rives)

Household and Domestic Piety

Romans also burned incense at home. The household shrine (lararium) received humble offerings—wine, garlands, small cakes, and pinches of incense—particularly on kalends, birthdays, and family rites. Varro’s language in De Lingua Latina for daily cult and Cicero’s references in De Legibus to household Lares assume a repertoire in which incense signaled reverence and marked thresholds.

As aforementioned, in domestic settings the acerra (incense casket) and turibulum (incense burner) appear in descriptions and on reliefs, indicating that ordinary households practiced small-scale fumigation. The same resins used in temples—frankincense, myrrh, storax—could be burned over charcoal, sometimes blended with spices or balms also used as perfumes.

Archaeology adds texture. Household shrines at Pompeii and Herculaneum preserve wall-paintings of Lares flanking a central altar; traces of heat and soot below such niches likely come from repeated burning. Portable bronze censers, some with long handles or chains, make sense of textual references to passing a censer during prayers. The domestic register of incense was intimate: a few grains, a spoken vow, a momentary cloud of scent shared by a family.

Because domestic cult was frequent, the economy of incense ancient Rome made provision for modest quantities. Shop lists and moralists’ complaints imply that small packets of resin were routine purchases.

While temples demanded steady supplies for the liturgical calendar, households kept incense among other consumables, alongside oil and wine. This banal presence underscores how familiar the act of burning incense was across the social spectrum. (Perfumery in in Ancient Greek and Roman Societies, by Benton Kidd; Introduction: People, Places and Rituals in the Religions of Rome, by Lauren Hackworth Petersen)

Funerary Rites and the Fragrant Dead

Incense attended the Roman dead. Literary descriptions and epitaphs imply fumigation at the house of the deceased, processional incense at the pompa, and offerings at the pyre or tomb. Myrrh and other aromatics appear among the substances scattered or burned, and Pliny notes deodorizing and preservative uses for resins.

Poets make the link explicit: “give me frankincense,” a mourner asks, “to honor the shade,” a formula that shows incense as a dignifying gift. In provincial contexts, traces of imported resins in graves suggest that long-distance aromatics reached far beyond Italy, granting Roman funerals a shared sensory vocabulary across the Empire.

Modern reassessments of “death pollution” in Rome have challenged the idea that fear of miasma dominated practice; instead, obligation and convention best explain the patterned use of aromatics around death. Mourners were bound to act—keep vigil, hire musicians, process, burn offerings—without assuming a metaphysical danger from corpses. Within that obligation, incense and spices addressed sensory, medicinal, and honorific aims: they sweetened the air, soothed bodies, and dignified the dead. (Re-examining Roman Death Pollution, by Allison L. C. Emmerson)

Incense, Politics, and the Boundaries of Loyalty

Emperors and governors understood the symbolism of incense. Public ceremonies that required a pinch of incense at an imperial altar made loyalty legible; refusal could be read as defiance. Later accounts of trials emphasize the act of “sacrificing” by incense before images—a minimal but decisive test.

Conversely, the staging of imperial benefaction used aromatics as spectacle: Suetonius’ Nero boasts banquet rooms whose mechanisms “rained flowers and perfumes,” and saffron mists perfumed theatres. Though exceptional, such scenes illuminate how elites could shape public air itself as a sign of power.

At more ordinary civic scales, incense unified festivals, processions, and anniversaries. Priests and magistrates processed with acerrae; boys and girls carried garlands; spectators smelled what they saw. To a Roman crowd, fragrance worked as cue and confirmation: the rite was authentic because it looked and smelled as custom prescribed. In this sense, Roman Empire incense was a social technology—an olfactory agreement about what religion felt like. (Imperial Cult and Native Tradition in Roman North Africa, by J. B. Rives)

Medicine, Magic, and Suspicion

Aromatics lived double lives. Medical writers—Dioscorides and later Galen—prescribed resins and spices as expectorants, antiseptics, and digestives; the same resins burned as incense could be macerated into medicaments. Pliny lists pharmacological virtues for storax, frankincense, and myrrh even as he censures overuse. Because the same substances crossed spheres, meaning shifted with context.

The very aroma that sanctified a temple could, when burned over a private charm, seem suspect.

Terracotta group of women seated around a well head, probably a local cult of Demeter and Kore who were widely worshipped in Southern Italy and Sicily from Ancient Greeks. Credits: The MET, Public domain

As long-distance trade expanded, Roman authors increasingly coded some eastern aromatics as exotic and morally ambivalent. Pliny rails at luxuria; satirists mock over-scented elites. In Late Antiquity, literary and documentary evidence associates certain Indian spices and aromatics with “magical” practices, showing how distance, rarity, and ritual use could shade into suspicion.

The Greek Magical Papyri prescribe blends that include storax or frankincense alongside invocations, while authors like Apuleius play with the boundary between medicine, magic, and popular belief. Even so, the same substances could be pious in one context (temple incense) and illicit in another (private spells), reminding us that meaning followed use rather than inhering in the goods themselves.

Trade studies caution against flat categories. Spices and aromatics could be both necessity and luxury: “necessary” in civic and funerary rites, “luxurious” when lavished at banquets.

Their value was situational, and Romans knew it. That is why the same shipment recorded on a papyrus can look like high finance to a merchant, moral danger to Pliny, and simple adequacy to a city magistrate provisioning a festival. (Indian Spices and Roman "Magic" in Imperial and Late Antique Indomediterranea, by Elizabeth Ann Pollard; The Reception and Consumption of Eastern Goods in Roman Society, by Matthew Adam Cobb)

Burners, Boxes, and Technique

As already mentioned, incense that ancient Rome burned required hardware. Acerrae (incense boxes) stored graded resins; turibula (censers) and thymiateria (pedestal burners) managed the fire. Archaeology and art show portable bronze turibula with swinging chains, pedestal burners in sanctuaries, and simpler household bowls.

Some have pierced lids to regulate burn rate; others have long handles to pass the ember-bed from person to person. Technique was simple but controlled: a bed of glowing charcoal; resins pinched or spooned from the acerra; occasional blending with wine-drops or oils to modulate smoke and scent.

Domestic shrines left heat-scars and soot signatures; sanctuaries curated the sensory environment through sheer scale—more burners, more smoke, more scent. The smellscape of a temple was managed deliberately: clean wood smoke for heat, resin for sanctity, and limits set by ritual handbooks about when, where, and how much to burn.

Material evidence also complicates social assumptions. Fine bronze thymiateria occur in elite houses and villas, but plainer ceramic or iron burners turn up in modest quarters. Incense, in other words, was not a purely elite privilege; quantity and quality varied, but the practice was broadly distributed, especially when tied to calendrical obligations. (Introduction: People, Places and Rituals in the Religions of Rome, by Lauren Hackworth Petersen)

Cost, Fashion, and Change Over Time

Incense sat at the intersection of religion and economy. Pliny’s complaint that silver hemorrhaged toward Arabia and India translates into real household budgets and civic outlays for festivals. Town councils funded incense for processions; collegia and priesthoods kept accounts; families portioned small stores for life events—birthdays, weddings, funerals.

The fashion cycle in aromatics is visible even beyond antiquity: later Near Eastern sources chart shifts after the seventh century CE, with camphor, agarwood, musk, and ambergris rising while older Mediterranean staples like balsam and myrrh receded. Those later transformations remind us that “incense” is a moving category: Romans burned what networks could reliably supply, and tastes and technologies changed.

The trade frameworks that brought resin to Rome also brought ideas about how to burn it. Learned discussions on grades and blends moved with merchants; temple keepers compared notes with physicians; householders learned by imitation in public rites. In this sense, incense was as much knowledge as commodity. Its use knit together places—from Dhofar and the Somali coast to Egyptian ports, to the Tiber—into a single ritual economy. (Trends in the Use of Perfumes and Incense in the Near East after the Muslim Conquests, by Amar Zohar and Efraim Lev)

Yes—Romans used incense widely. In temples, its smoke marked proper approach to the gods; in homes, it framed daily piety; in funerals, it honored the dead and managed the senses; in politics, it drew a bright line of loyalty around the imperial image. In art, it invoked the creation of wonderful items that awe even today’s modern audiences.

Behind that familiar fragrance stood distant groves, monsoon sailing, brokers and taxes, and a Roman debate about luxury and propriety. To study Roman Empire incense is to see how a small, combustible gift connected households to altars, provinces to the capital, and ritual practice to the roads and sea-lanes of an empire.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: