The Gemonian Stairs: Rome's Spot of Mourning and Execution

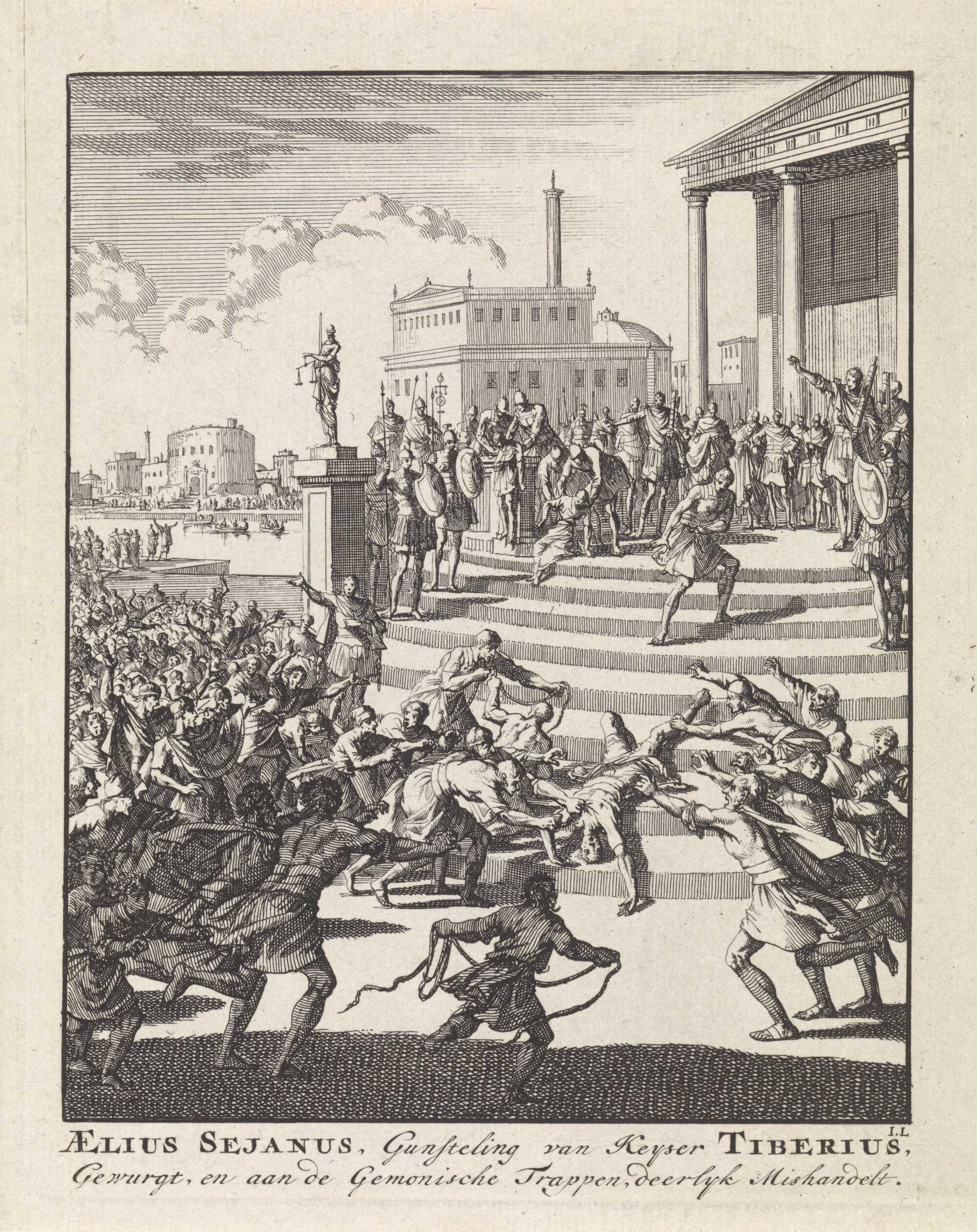

The Gemonian Stairs became synonymous to death and humiliation for the Roman Empire's enemies and criminals.

Throughout the Roman Empire history, there is a place spoken of with dread. It is the Scalae Gemoniae, or the Gemonian Steps. These seemingly innocuous steps, located in the heart of Ancient Rome, became synonymous with death and disgrace, often serving as the final destination for the empire's enemies and criminals.

Detention and Execution in Ancient Rome

Post-mortem humiliation was sometimes integral to capital punishment, with the public display of executed bodies serving as a stark deterrent to onlookers. Such displays, often positioned at the periphery of towns or within cemeteries, made a harsh contrast with the graves of honored citizens.

In Rome, bodies of executed criminals were sometimes discarded into the Tiber, while high-profile traitors—formerly powerful or noble figures—might be exposed on the Gemonian Steps in the heart of the city, visible from the Forum. Accounts from Tiberius’s reign reveal his notorious use of these steps for numerous condemned victims, symbolizing the harsh consequences of treason.

The fear of public execution followed by mutilation of the corpse, drove some individuals to take their own lives and to ensure that their bodies were swiftly handled by others. Decapitation was a frequent form of post-mortem abuse, as the head, with its recognizable features, made it ideal for display and defilement.

The heads of those labeled as public enemies were often placed on the rostra in the Roman Forum—such as Cicero’s head and right hand, displayed there after his assassination in 43 BC. Similarly, Emperor Galba’s head endured extensive abuse before his remains finally received a proper burial. Not all bodies, however, received honor in death or reached their final resting places intact and with dignity. (Death in Ancient Rome, by Valerie M. Hope)

"Three hundred men were put to death by proscription.

Antony gave orders to those who killed Cicero to cut off his head and right hand, the hand with which Cicero had written his speeches against him; and, when they were brought before Antony, he gazed upon them joyfully, actually laughing out loud several times.

When Antony had satiated himself with the sight of them, he ordered them to be placed on the rostra in the Forum, as though he was insulting the dead rather than displaying his own insolence and abuse of the power that Fortune had given him"

"Galba was killed beside the Lake of Curtius [in the Roman Forum], and was left lying just as he fell.

A common soldier returning from the grain distribution put down his load and cut off the head.

Then, since there was no hair by which to carry it, he placed it under his cloak and later thrust his thumb into the mouth, and so took it to Otho.

Otho handed it over to a crowd of servants and camp-followers, who stuck it on a spear and paraded it round the camp … [while singing insults] …

A freedman of Patrobius Neronianus bought the head for 100 gold pieces and threw it down at the place where Patrobius had been executed at Galba’s orders.

At last Galba’s steward Argivius took it, with the rest of the body, to the tomb in Galba’s private gardens on the Aurelian Way."

Suetonius, Galba

The Carcer and Lautumiae

It is important to review all steps that led to an individual’s body being sent to the Gemonian Steps, so we can have the full picture. According to Roman tradition, Ancus Marcius, the fourth king of Rome, built the prison (carcer) in the city, while Servius Tullius, the sixth king, added the underground section called the Tullianum. The seventh king, Tarquinius Superbus, introduced other punitive measures, including the lautumiae, stone quarries used for detention, likely inspired by the Greek practice in Syracuse.

The carcer served as a secure place for criminals awaiting trial or execution, while the lautumiae could hold larger numbers with minimal oversight. Various instances in history highlight the prison’s role in notable imprisonments, including that of the deposed decemvir Ap. Claudius and M. Manlius.

For the Christian faith, St. Agatha of Sicily’s incarceration is one of the most well known stories regarding Roman jails.

A painting by Simon Vouet, of Saint Peter visiting Saint Agatha in Prison. Public domain

Over time, the carcer was fortified, especially after the vulnerability revealed in a potential 385 BCE attack. By the third century, it had been reconstructed with harder stone, indicating its evolution. Later, during key events such as the Gracchan disturbances and the rise of prominent figures like Marius, the carcer continued to play a critical role in Rome’s judicial system.

The Saxum Tarpeium

The Tarpeian Rock, was a site in ancient Rome used for executions by throwing condemned individuals off its cliffs. The rock’s name is associated with a Roman officer’s daughter who betrayed the city to the Sabines. It was located on the southeastern side of the arx and overlooked the Forum.

The first recorded execution occurred during Romulus' reign, when pirates were allegedly executed. Over time, various figures were executed or threatened with execution at the Tarpeian Rock, including political opponents, military deserters, slaves, and rioters. The rock’s use as a punishment is frequently mentioned throughout Roman history, with significant instances occurring from the early monarchy through the reign of emperors such as Tiberius and Claudius.

Typically, tribunes of the plebs carried out these executions, sometimes following formal condemnation and sometimes acting on their own authority. Other officials, including quaestors and consuls, also ordered executions here. Some notable executions include M. Manlius in 384 BC for aspiring to kingship, and numerous political opponents during the Marian and Sullan conflicts.

The Tarpeian Rock remained a symbol of severe punishment and was referenced by historians like Seneca as a longstanding institution in Roman justice.

Tarpeian Rock painting by Francis Towne. Public domain

The Scalae Gemoniae

The Scalae Gemoniae, or the "staircase of wailing," was a site in ancient Rome where the bodies of executed individuals were exposed to the public. Relatives would mourn the deceased, while enemies might taunt and abuse the corpses. The staircase led downhill from the arx to the carcer and was visible from the Forum.

The name "Scalae Gemoniae" appears to reference this grim practice of exposing the dead, though Tacitus referred to it as the "centum gradus" (hundred steps) in some contexts, which creates ambiguity about whether it was directly connected to the Tarpeian Rock. Evidence of the Scalae Gemoniae being used for this purpose is not well-documented for the Republic but became prevalent under the rule of Tiberius, with several high-profile executions and public exhibitions, such as that of Sejanus and his children.

Bodies would be left on the steps for days and then dragged to the Tiber for disposal. This gruesome display was part of Rome's public system of punishment and served as a stark reminder of the state's power. (The Roman carcer and its adjuncts, by T. J. Cadoux)

The Stairs of Violence and Howl

It is believed that it was under Tiberius, when the Scalae Gemoniae became the prominent place where the bodies of criminals executed by the state were exposed. This staircase, located at the northern corner of the Forum Romanum, played a significant role in execution rituals during the Roman Empire.

The historians note that these stairs symbolized the suppression of popular participation in judicial matters, a shift that began in the late Republic and continued into the Principate. Although sources detail various trials and convictions of capital crimes, they rarely provide detailed descriptions of the execution processes.

However, it is possible to discern some elements typically involved in executions linked to the Scalae Gemoniae.

The location of the Gemonian Stairs, today. Credits: RussieseO from Getty Images, by Canva

After condemnation by the emperor or the Senate, the victim was usually taken to the carcer, where they were likely strangled, sometimes after a delay of several days. In some instances, individuals were thrown from the Tarpeian Rock instead.

Following death, the body was cast onto or near the Scalae Gemoniae, remaining exposed for a few hours or even several days. During this time, observers could either mourn or attack the corpse, and it was common for people to mutilate it. Once this period ended, the body was dragged away by a hook and thrown into the Tiber.

One of the most famous individuals subjected to this treatment was Sejanus, whose body, along with those of his children, was exposed on the steps after their execution. Similarly, Titius Sabinus was convicted of conspiracy against the emperor and his body abandoned on the Scalae Gemoniae in AD 28.

Agrippina, condemned in the following year, avoided a similar fate only because Tiberius refrained from having her strangled and cast onto the steps. The exposure of high-ranking individuals on the steps appeared to be closely associated with treason or perceived threats to the state, and their relatives, friends, or slaves might face a similar fate.

Cassius Dio notes in his Roman History about Sejanus:

The populace also assailed him, shouting many reproaches at him for the lives he had taken and many jeers for the hopes he had cherished.

They hurled down, beat down, and dragged down all his images, as though they were thereby treating the man himself with contumely, and he thus became a spectator of what he was destined to suffer.…

For the moment, it is true; he was merely cast into prison, but a little later, in fact, that very day, the senate associated in the temple of Concord not far from the jail, when they saw the attitude of the populace and that none of the Pretorians was about, and condemned him to death.

By their order he was executed and his body cast down the Stairway, where the rabble abused it for three whole days and afterwards threw it into the river.”

Lower-class criminals, prisoners of war, and slaves were likely executed and exposed elsewhere in the city, such as outside the Esquiline Gate or crucified along roads leading into Rome. The practice of exposing bodies on the Scalae Gemoniae dates back to the late Republic, when civil wars and proscriptions led to similar displays in the forum. For instance, the proscriptions of Sulla and the triumvirs showcased heads and body parts on the rostra, not far from where the stairs were later constructed.

During the reign of Augustus, construction work on the northern part of the forum, including Tiberius’ restoration of the Temple of Concord, possibly led to the Scalae Gemoniae replacing the older Gradus Monetae staircase. This marked a shift from informal exposure practices in the Republic to more institutionalized execution rituals during the imperial period. The first references to the Scalae Gemoniae come from Valerius Maximus, writing in AD 30, and the practice of exposure became solidified by AD 31 with the fall of Sejanus.

"Severity, hitherto a most rigid guardian and protector of liberty, was equally as fierce also in the preservation of discipline and dignity.

For the senate delivered M. Claudius to the Corsicans, because he had concluded an ignominious peace with them. And because they would not receive him, they caused him to be put to death in prison.

When once the majesty of the empire was impaired, in how many ways did obstinate anger vindicate it!

They nullified the accord, they deprived him of his liberty and life, and dishonoured his body with the ignominious contumely of the prison, and the Gemonian Steps."

Valerius Maximus

Under Claudius, the bodies of those executed in the city, including heads of those killed outside Rome, were displayed on the steps. In AD 69, during the Year of the Four Emperors, the steps became a prominent site of violence and display, and in AD 106, Trajan had the head of Decebalus, the Dacian king, sent to Rome and thrown down the Scalae Gemoniae.

The practice of exposure on the Scalae Gemoniae extended into later centuries. For instance, Tertullian mentioned the steps when criticizing the Valentinian heretics, and Sidonius Apollinaris' friend Arvandus, jailed on Tiber Island in AD 469, feared “the hook, the Stairs, and the noose,” a sign of the continued association of the Scalae Gemoniae with punishment and death even in later periods.

Exposing the corpses of criminals on the Scalae Gemoniae was deeply embedded in Roman societal and spiritual beliefs, reflecting the Graeco-Roman concept that the unburied dead would suffer a restless existence, eternally marked by shame. This form of punishment denied the deceased the honor of a grave, severing them from both the living world and any possible memorials of their achievements. Their bodies, abandoned on the steps or thrown into the Tiber, stood as a stark reminder of their disgrace and of state power.

Politically, the exposure ritual marked the shift from public participation in executions during the Republic to a more restricted, state-dominated process in the Empire. This was part of a broader transition in which capital punishment became an assertion of imperial authority, allowing the emperor to demonstrate his control.

Unlike the Republican era, when condemned individuals were led publicly to execution sites like the Tarpeian Rock, the imperial process limited public intervention but used the exposed bodies on the Scalae to continue a form of communal “separation” ritual. The steps’ strategic location near symbols of judicial and religious power, such as the Capitoline Hill, the Roman forum, and the Curia, emphasized the state’s authority in the execution process.

Here, crowds could easily witness the punishment, reinforcing the severity of treason or political dissent. This visibility and accessibility also served as a public deterrent, announcing the crime and punishment to the populace and signaling the emperor’s power to control political order. (Mutilation, and Riot: Violence at the "Scalae Gemoniae" in Early Imperial Rome, by William D. Barry)

Transformation into a Site of Execution

The condemned, as aforementioned, were often strangled in prison, because just falling down the stairs would not be fatal most of the times and then their lifeless bodies were thrown down the steps for the public to see, serving as a gruesome warning against defying the state's authority.

Sometimes though, the procedure was different.

Those sentenced to a dishonorable demise would first be executed atop the stairs, their bodies subsequently cast down the steps. Left exposed for several days, the remains would be subject to scavenging by dogs and birds of prey, culminating in their eventual disposal into the Tiber River dragged off with a hook.

This practice of both execution and public humiliation of the corpse, cemented the stairs' reputation as a symbol of imperial judgment and the retribution that awaited Rome's traitors. When the body of Lucius Aelius Sejanus (as we mentioned above, the Prefect of the Praetorian guard and confidant of Tiberius, who plotted against him) the crowd was in such a state of a frenzy that tore his body into pieces by their bare hands.

In a twist of fate, upon Tiberius's assassination—suffocated in his sleep by Caligula and his collaborators—crowds congregated at the stairs, chanting "Tiberius to the Tiber" and demanded that his body be displayed on the steps.

Suetonious writes about Tiberius in The Lives of the Twelve Caesars:

“The people were so glad of his death that at the first news of it, some ran about shouting, “Tiberius to the Tiber,” while others prayed to Mother Earth and the Manes to allow the dead man no abode except among the damned.

Still, others threatened his body with the hook, and the Stairs of Mourning, especially embittered by a recent outrage, added to the memory of his former cruelty.”

A "Stage" of Horror

The exact appearance of the Scalae Gemoniae remains a subject of speculation among historians and archaeologists. The stairs were likely made of stone, well-worn by the passage of countless feet over the years. It is not absolutely sure where the stairs were exactly, but they probably stretched down from the summit of the Capitoline Hill, cutting through the Roman topography to connect with the central forums below.

Executions at the Gemonian stairs held a profoundly theatrical quality, especially given the location. The stairs ascend from the Forum Romanum up the Capitoline hill, skirting the Temple of Concord—a setting that adds symbolic weight. This visible and central spot within Rome, frequently traversed by its citizens, ties the act of execution directly to Rome’s core values, historical consciousness, and societal identity.

This prominent placement meant that the spectacle of death they hosted was not easily ignored and served as a daily reminder of the consequences of crossing the Roman Empire.

A painting of Gustave Housez, the death of Roman Emperor Vitellius, possibly at the Gemonian Stairs. Credits: VladoubidoOo, CC BY-SA 4.0

Witnessing these punishments reinforced the notion that harmony and social order had been restored, a message amplified by the Temple of Concord's proximity. As bodies tumbled down, visibly desecrated, they symbolized the state’s power to restore justice; these corpses, rejected by society, could “rejoin” the public only after paying for their transgressions. Tacitus vividly illustrates this in his account of Vitellius, the “flash-emperor,” whose fall was another moment of grim spectacle reinforcing Rome’s devotion to order.

"[Vitellius’] hands were bound behind his back, and he was led along with tattered robes, a revolting spectacle, amidst the invectives of many, the tears of none.

The degradation of his end had extinguished all pity. [...]

Vitellius, compelled by threatening swords, first to raise his face and offer it to insulting blows, then to behold his own statues falling round him, and more than once to look at the Rostra and the spot where Galba was slain was then driven along till they reached the Gemoniae, the place where the corpse of Flavius Sabinus had lain.

One speech was heard from him shewing a spirit not utterly degraded, when to the insults of a tribune he answered, "Yet I was your Emperor."

Then he fell under a shower of blows, and the mob reviled the dead man with the same heartlessness with which they had flattered him when he was alive."

A brief stroll from the widely recognized Gemonian Stairs, down Via di San Pietro in Carcere, beyond the Tabularium, and adjacent to the ancient Mamertine Prison, lies a slender staircase. This pathway is believed to be the site (or potentially the terminus) of the historical stairs, with the assumption being that these two staircases were interconnected in the past.

The precise timing of the stairs' construction remains unclear to historians, as there are no direct references to their inception in historical texts. The blood shed on them though, will remain in history.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: