Drusus the Elder: Rome’s Most Successful Germanic Commander

Rome’s deepest advance into Germania was led not by a veteran general, but by a man in his twenties. Nero Claudius Drusus carried Roman power farther north than any commander before him, before his sudden death froze an unfinished conquest into legend.

In the final decades of the first century BCE, Rome looked north with a mixture of confidence and unease. The Rhine marked a frontier that had been crossed before, but never held for long, and memories of earlier disasters still lingered beneath Augustan stability. It was into this uncertain landscape that Nero Claudius Drusus was sent. Young, ambitious, and closely bound to the ruling house, Drusus did more than raid across the frontier. He carried Roman power deep into Germania, not as a response to crisis, but as a deliberate project of expansion–one that would briefly redraw the map of Rome’s northern world.

Drusus the Elder and the Making of a Roman Legend

Across modern Germany, the name of Nero Claudius Drusus survives quietly in street names–Drususgasse here, Drususstraße there–often unnoticed by those who pass through them. In Cologne, one such street lies close to the cathedral and the Roman-Germanic Museum, surrounded by reminders of the city’s ancient past.

That a Roman commander should be commemorated in this way is unremarkable; that this particular commander is remembered at all is more curious. Drusus the Elder, despite his prominence in Roman eyes, has largely faded from popular memory.

The title “Drusus the Elder” can be misleading. It suggests age, long experience, and a lifetime of campaigning. In reality, Drusus was astonishingly young. When Augustus entrusted him with an army, he was only twenty-three. Within a year, working alongside his brother Tiberius, he subdued communities in the central and eastern Alpine valleys. What followed was a career compressed by time but dense with achievement.

Drusus oversaw extensive military construction, laying down roads, forts, and supply networks that helped anchor Roman power along the Rhine. In the process, he played a role in the early development of settlements that would later become major cities of the region.

His activities were not confined to land. Drusus pushed Roman exploration further north than any predecessor, combining riverine, maritime, and overland movement in a way that expanded Rome’s geographical knowledge. He also pursued diplomacy alongside force, securing alliances with tribes across the Rhine and extending Roman influence as far as the Elbe. These actions were not peripheral skirmishes but part of a broader reorientation of Rome’s northern frontier.

Drusus’ private life reinforced his public stature. He married Antonia, daughter of Mark Antony, and fathered children who would shape imperial history: Germanicus, celebrated as Rome’s golden prince; Livilla; and Claudius, the future emperor. Within the Julio-Claudian family, his line proved unusually consequential. When Drusus died suddenly at twenty-nine, he was mourned not as an ageing commander but as a charismatic figure cut down at the height of promise.

Contemporary Romans treated him as a hero of near-mythic stature. Statues were raised in his honour, Augustus composed a biography of him, and later emperors–especially Claudius–cultivated his image as the youthful conqueror of Germania. Writers such as Pliny the Elder devoted extensive attention to his campaigns north of the Rhine.

Yet over time, Drusus slipped from view. Modern readers encounter him mainly as a supporting figure in Augustan history or as a prelude to the catastrophe of Teutoburg. No ancient biography survives intact. Augustus’ memoir is lost, as is Pliny’s detailed account. What remains is a patchwork assembled from later authors–Cassius Dio, Livy, Suetonius, Velleius Paterculus, Florus, Horace, and others–each preserving fragments of a life that must be reconstructed indirectly. Even so, enough survives to trace his career with reasonable clarity and to glimpse his character.

From an early age, he lived at the intersection of politics and war. His connection to Augustus ensured early entry into public life, but advancement followed demonstrated competence rather than mere favour. His military experience began in the Alpine campaigns and culminated in operations beyond the Rhine, in regions the Romans grouped under the name Magna Germania–lands poorly mapped, imperfectly understood, and freighted with fear.

For Roman soldiers, these expeditions meant marching into territory shaped as much by legend as by intelligence, where forests, rivers, and unfamiliar peoples were imagined as hostile and monstrous.

Drusus led these campaigns without the advantages later generations would take for granted. There were no reliable maps, no rapid communications, and no comprehensive reconnaissance. Decisions depended on local intelligence from allies and captives, the reports of scouts, and a commander’s instinct for terrain and enemy behaviour.

Roman command culture recognised these limitations and compensated by granting wide discretion to generals in the field. Drusus thrived in this environment. He led from the front, earning loyalty through personal courage and decisiveness. At the same time, this boldness carried risks. His readiness to expose himself–and by extension his troops–to danger sometimes bordered on recklessness.

Rumours, Divorce, and the Question of Paternity

In the months before Drusus’ birth, Rome was alive with rumour. Livia Drusilla was already pregnant when Octavian divorced Scribonia and moved with striking speed to marry her, prompting widespread speculation that the child she carried was his. The timing alone was enough to provoke comment, and satirical verse soon gave voice to public suspicion:

“Nine months for common births the fates decree; But, for the great, reduce the term to three.”

The matter could not be left to gossip. Because Livia was visibly pregnant, Octavian sought a formal ruling from the collegium pontificum on whether the marriage could proceed. Roman law allowed remarriage during pregnancy only if paternity was beyond doubt. In this case, the facts were decisive. Livia had been absent from Rome for much of the relevant period and had returned only in the summer, making Octavian’s paternity impossible. The pontiffs confirmed the conception and authorised the marriage.

Drusus was born on 13 January 38 BCE. Despite Livia’s remarriage, Roman law placed him under the authority of his biological father, Tiberius Claudius Nero, who formally acknowledged the child during the lustratio ceremony nine days later and gave him the name Decimus Claudius Drusus. Whatever suspicions had circulated in Rome, Drusus entered public life as a legitimate member of the Claudian line, his status affirmed both legally and ritually.

An Inheritance of Names, Virtues, and Memory

Drusus and his elder brother Tiberius spent their early years under their father’s authority but within the orbit of their mother’s household on the Palatine. Their upbringing combined conventional Roman education with something more demanding: constant exposure to ancestral precedent. The Claudian family history–preserved in memory, ritual, and wax masks–presented a lineage marked by severity, ambition, and public service.

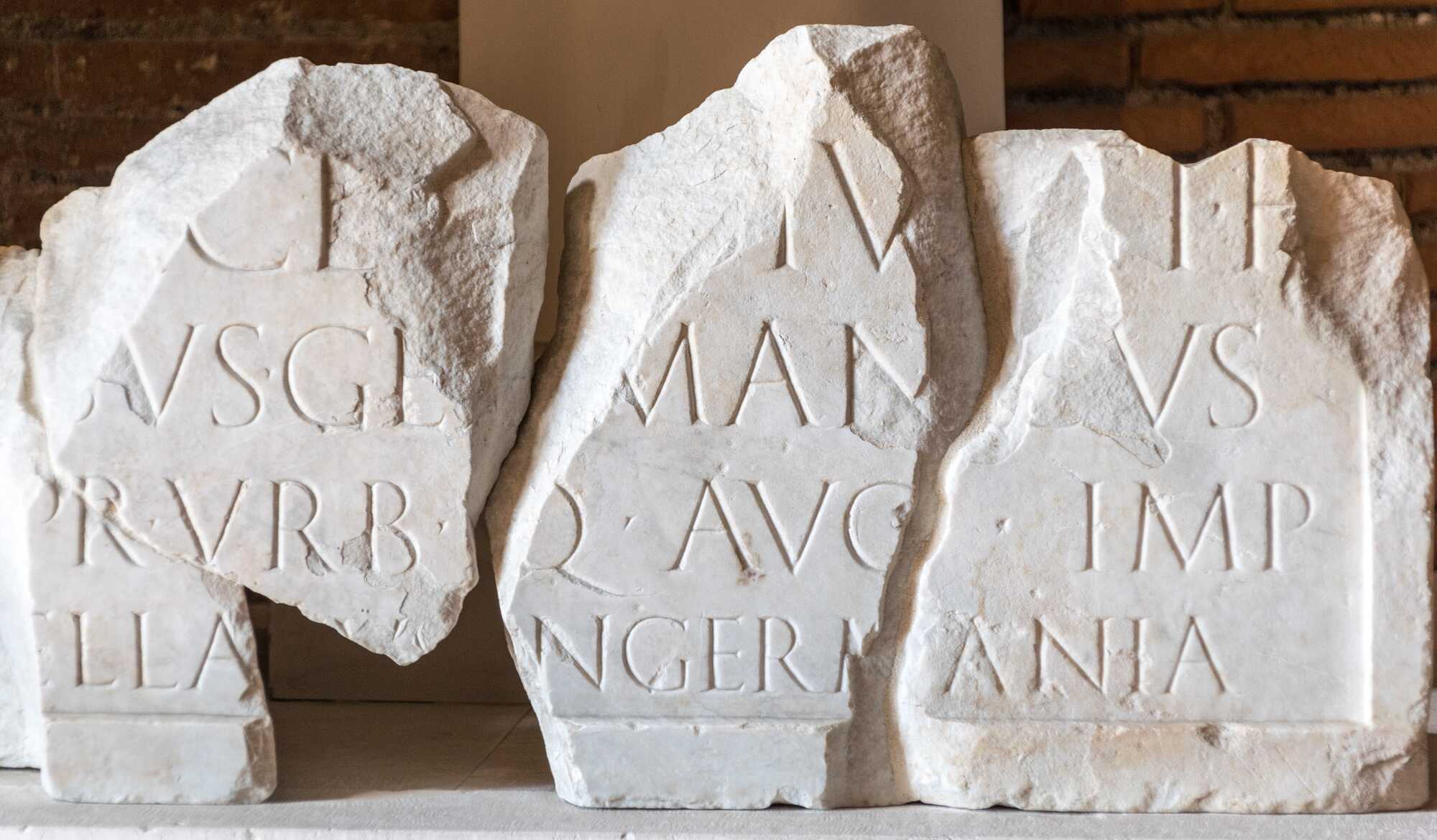

![Latin inscription from the Roman period discovered in 1952 on the island of Vis (ancient Issa ) and preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Split. Latin text: "Drusus Caesar, T[(iberii) Aug(usti) f(ilius), Diui] / Augusti nepos, consul de[sign(atus) II], / pontifex, augur, camp[um dedit] / Publio Dolabella leg(ato) pro[praetore].](https://romanempiretimes.com/content/images/2026/02/latin-inscription-drusus-caesar--1--1.jpg)

Cicero offers a rare contemporary glimpse of Nero’s character, praising his gratitude and personal integrity while hinting at the optimism that would later prove politically costly:

“There is no one among the noble families whom I value more highly… he is the most grateful fellow in the world.” (Cicero, Letters)

Nero’s repeated political misjudgements eventually forced the family into flight during the civil wars, a formative experience that ended with his early death in 33 BCE. After this, Drusus moved permanently into his mother’s household under Augustus’ supervision. His education continued within the cultural and political centre of the new regime, shaped as much by public spectacle and ancestral expectation as by formal instruction.

From an early age, Drusus was taught not only how Romans learned, but how Romans remembered–and what was expected of a name that carried such weight.

The Lollian Disaster and a Shock to Roman Confidence (17 BCE)

In the late summer of 17 BCE, Rome received alarming news from Gallia Belgica. Roman forces under the governor Marcus Lollius suffered a serious defeat at the hands of a Germanic coalition led by the Sugambri, with Cherusci and Suebi allies. The loss of the legionary eagle of Legio V Alaudae marked the event as a national humiliation, not merely a battlefield setback. For Augustus–who had recently celebrated the recovery of standards lost at Carrhae–the incident was both politically and personally damaging.

Although the Germanic forces soon withdrew across the Rhine and offered hostages, the episode exposed the vulnerability of Rome’s northern frontier and shattered the illusion that Gaul was secure.

The Lollian Disaster triggered the most significant reassessment of Rome’s northern policy since Caesar’s Gallic Wars. Augustus recognised that peace in Gaul was impossible while Germanic groups could raid freely across the Rhine. The frontier was not a fixed line but a porous zone, difficult to police and prone to instability.

Rather than rely on reactive defence, Augustus moved toward a strategic solution: securing the Alpine corridors and repositioning Roman military power to control movement between Italy, Gaul, and the Danube basin.

Drusus’ First Test: Command in the Alps

With Agrippa unavailable and Tiberius already governing Gaul, Augustus made a bold decision. In 16 BCE, he entrusted Nero Claudius Drusus, only twenty-two years old and without prior field command, with leadership of the Alpine campaign (Bellum Alpinum).

The appointment was risky but calculated. Drusus would be closely supported by experienced officers, while Augustus and Tiberius remained nearby. The campaign would test whether the youngest Claudian possessed the balance of caution and boldness Augustus prized in commanders.

Drusus’ campaign proved swift and effective. Roman forces defeated the Raeti and related Alpine peoples, secured the main passes, and established permanent routes through previously hostile terrain. The conquest opened a continuous land corridor linking Italy to the Rhine and Danube–an achievement with lasting strategic consequences.

The success earned Drusus immediate promotion and public acclaim. Augustus celebrated the victory as his own in official propaganda, while poets like Horace elevated Drusus as a youthful embodiment of Roman virtus.

In late 15 BCE, Drusus returned briefly to Lugdunum, where Augustus reassigned responsibilities. Tiberius returned to Rome, while Drusus assumed the post of legatus Augusti pro praetore of the Tres Galliae.

The decision marked a turning point. No longer a promising youth on trial, Drusus now held independent command over Rome’s most sensitive frontier. The Alpine victories were not an endpoint but a prelude to a far larger project: the Roman advance into Germania itself.

Governing a Region in Transition

When Nero Claudius Drusus assumed command in late 15 BCE, he inherited a Gaul that was neither newly conquered nor fully integrated. Julius Caesar’s tripartite division of Gaul still defined the landscape, but Augustus used his recent visit to reorganise the territory into three roughly equal imperial provinces–Aquitania, Belgica, and the newly created Gallia Lugdunensis–collectively known as the Tres Galliae. This restructuring aimed to stabilise administration, balance provincial power, and accelerate integration into the Roman system.

Unlike Narbonensis, which had long been settled and Romanised, the Tres Galliae remained unevenly developed. Urbanisation was limited, investment cautious, and much of the population still lived near traditional oppida. Under Augustus, policy shifted decisively: Gaul was no longer just a defensive buffer but a region with economic and political potential.

Drusus’ mandate was to consolidate peace, promote urban growth, secure taxation, and protect Roman interests–while preparing the ground for expansion beyond the Rhine.

This work required both restraint and pressure. Roman administration brought censuses, taxation, and the steady intrusion of imperial oversight into daily life, binding local elites to Rome while provoking resentment among others. Drusus’ task was to enforce these measures without destabilising the region at the very moment it was expected to support large-scale military operations. Gaul was no longer a conquered territory, but it was not yet secure–and its stability was essential to any advance beyond the Rhine.

Lugdunum: Capital of the New Gaul

Drusus and his household took up residence in the praetorium at Lugdunum, a monumental governor’s palace overlooking the Rhône–Saône confluence. Founded as a colony in 43 BCE, Lugdunum had become the administrative heart of Gaul. Its forum, theatre, and infrastructure symbolised Rome’s ambitions for the region.

The city also housed the imperial mint, which from 15 BCE produced gold, silver, and bronze coinage for Gaul and the Rhine armies–making financial stability and military pay a core responsibility of Drusus’ governorship.

Augustan policy focused on winning over local aristocracies. Gallic tribes were reorganised into self-governing civitates modelled on Roman municipal structures, with councils, magistrates, and legal courts. Elite competition was encouraged through imperial patronage, civic privilege, and the granting of Roman citizenship. New towns bearing Augustus’ name became regional centres of prestige. This strategy fostered loyalty and passivity, binding Gallic leaders to Rome’s success while gradually dissolving older power structures.

Urban development remained uneven. Some planned towns flourished; others stagnated or were quietly ignored by the local population. Many Gauls preferred smaller villages (vici and pagi) that grew organically around roads, rivers, and military needs. While this supported trade and supply, it also revealed the limits of imposed Roman models.

Discontent surfaced most clearly in taxation, exemplified by the scandal of the procurator Licinus, whose abuses provoked formal complaints to Augustus–demonstrating both the risks of corruption and the functioning of imperial oversight.

Taxation replaced wartime levies of men and horses. Regular censuses assessed land, property, and slaves in detail, feeding imperial revenue and financing future campaigns. Though efficient, the process intruded deeply into private life and fuelled resentment among some communities. Loss of privileges and citizenship followed resistance. Drusus’ challenge was to enforce these measures without undermining the fragile loyalty Augustus sought to cultivate.

An Amphibious Invasion Strategy

In spring 12 BCE, Drusus launched an ambitious campaign combining land and sea power. From Batavian territory, Roman forces embarked on a large-scale amphibious operation designed to surprise the enemy, move troops and supplies together, and bypass difficult terrain. Purpose-built vessels transported soldiers, cavalry, animals, and equipment, demonstrating Rome’s logistical flexibility.

What followed was not merely coastal reconnaissance, but a sustained advance into the interior of Germania itself.

Using inland waterways and canals, the fleet reached the North Sea and advanced along the coast–an unprecedented Roman manoeuvre. Along the way, Drusus prioritised diplomacy. He secured alliances with local peoples such as the Frisians, gaining guides, manpower, and regional stability without bloodshed.

The expedition pushed further north than any Roman force before it. Some elements explored beyond the Elbe toward the lands of the Cimbri, extending Roman geographic knowledge as much as military reach. Elsewhere, Roman troops advanced inland along the Ems River, where resistance finally emerged. A naval engagement with the Bructeri ended in Roman victory, confirming control of the waterways.

Late in the season, misjudged tides nearly stranded the fleet on the coast, but allied forces helped avert disaster. With winter approaching, Drusus withdrew to the Rhine camps–having achieved strategic success without permanent occupation.

Drusus returned to Rome to widespread acclaim. He had exposed and crushed a Gallic conspiracy, secured the Rhine frontier, forged new alliances, carried out a successful amphibious invasion, and ventured farther north than any previous Roman commander. Contemporary coinage, official inscriptions, and later literary praise framed the campaign as a landmark achievement of the Augustan age.

Reward followed. Drusus was appointed praetor urbanus, a prestigious office that placed him firmly on the path to the consulship. At just twenty-six, he was already being compared to Alexander the Great–a parallel consciously cultivated in Roman memory.

The year ended on a sombre note with the death of Agrippa, Augustus’ closest associate. Power within the imperial family shifted, elevating Tiberius and reshaping dynastic plans. For Drusus, the future remained open. His achievements had secured Rome’s northern frontier and expanded its horizons–but they also drew him deeper into the ambitions and expectations of the Augustan regime.

A Conspiracy Exposed and the Opening of the German War

Drusus governed the Tres Galliae independently from Lugdunum. Although the provinces appeared stable, underlying resentment persisted among segments of the Gallic aristocracy, shaped by the legacy of Caesar’s conquest and intensified by ongoing administrative reforms. The census in particular appears to have provoked opposition, and some tribal leaders may have viewed the youth of the governor and the redeployment of legions to the Rhine as an opportunity to challenge Roman authority.

Drusus uncovered the conspiracy before it could be enacted. Although the means by which the plot was revealed are not recorded, the provincial administration possessed an extensive intelligence and policing apparatus, including military officials, road-station personnel, scouts, and a permanent paramilitary force guarding the imperial mint at Lugdunum.

Information was likely supplied by local elites who remained loyal to Rome and to Drusus personally. Acting swiftly, Drusus summoned leading Gallic figures under the pretext of a religious gathering, while troops were dispatched to secure potentially hostile territories. The stratagem isolated the conspirators and prevented coordinated resistance.

At the same time, Germanic groups east of the Rhine, particularly the Sugambri and their allies, attempted to exploit the situation. Drusus allowed them to initiate hostilities, then responded decisively. Roman forces repelled the incursions, crossed into enemy territory via the Batavian lands, and devastated the regions of the Usipetes and Sugambri, neutralising the immediate threat along the Rhine frontier. With the Rhineland secured, preparations for a full-scale offensive could proceed.

In the spring of 12 BCE, Drusus launched the first phase of the Bellum Germanicum. The campaign opened with an amphibious operation departing from Batavodurum, employing a purpose-built fleet to transport legions, cavalry, and supplies. The use of naval routes enabled a rapid advance and avoided the logistical constraints of overland movement.

The fleet moved through the Drusian canal system into Lacus Flevo and onward toward the North Sea, establishing contact with coastal peoples. The Cananefates were encountered without resistance, while the Frisii were brought into alliance through treaty and subsequently contributed troops to the Roman cause.

Continuing along the coast, Roman forces advanced to the mouth of the Ems River and penetrated inland. During operations on the river, the fleet was attacked by the Bructeri, but the assault was repelled, and Roman control of the waterways was maintained. As the campaigning season drew to a close, Drusus ordered a withdrawal. During the return voyage the fleet was briefly endangered by misjudged tides off the Frisian coast, but assistance from allied communities enabled a safe retreat to the Rhine.

The first campaign season concluded with significant achievements: the suppression of internal unrest in Gaul, the defeat of hostile Germanic groups along the Rhine, the establishment of new alliances, and the extension of Roman military reach farther north than ever before. Drusus returned to Rome during the winter, where his successes were publicly recognised, marking his emergence as the principal commander of Rome’s northern war effort.

Turning Point: Omen, Anxiety, and Withdrawal

During the advance deep into Germania, Drusus experienced an episode that ancient authors interpreted as a supernatural warning. Cassius Dio records that a woman of immense stature appeared to him at night, addressing him in Latin and foretelling that he would not be permitted to see all the lands ahead, nor to survive the campaign.

Suetonius similarly describes the encounter as an apparition. Such experiences were not dismissed in Roman culture, where nocturnal spirits, divine visitations, and ominous dreams were accepted features of the world and were often treated as meaningful communications from the divine.

Whether understood as a supernatural visitation or as the product of physical exhaustion and psychological strain, the episode appears to have had a real effect on Drusus. He ordered the construction of a trophy on the far bank of the river, commemorating Roman success against the Marcomanni and marking the furthest point yet reached by a Roman army in Germania. Known later as the Tropaeum Drusi, it was remembered as a symbolic boundary of Roman expansion. Having done so, Drusus halted the advance and ordered the army to return toward the Rhine.

Omens in the Ranks and the March Home

As the army withdrew, ancient sources describe a growing atmosphere of unease. Soldiers reported unsettling sights and sounds: wolves prowling the edges of the camp, unexplained cries, phantom figures, and strange celestial phenomena. Shooting stars were seen in the night sky, interpreted as further signs of impending disaster. These reports reflect the heightened anxiety of troops operating far from familiar territory, at the edge of the known world, and may also point to the psychological toll of prolonged campaigning.

The march back followed the outbound route through forests, wetlands, and river crossings. Somewhere between the Saal and the Weser rivers, disaster struck. Drusus suffered a serious accident when his horse fell, crushing his leg. Ancient sources differ on the precise cause of his decline, but Livy records that the fall resulted in a fracture, a detail consistent with the severity of the injury and its consequences.

Injury, Medical Care, and Decline

Drusus received immediate medical attention. As a commander of consular rank, he would have been treated by a personal physician trained in Greek medical traditions, familiar with established techniques for diagnosing and treating fractures. Ancient medical knowledge allowed for the cleaning of wounds, resetting of bones, splinting, and bandaging, but severe injuries carried grave risks, particularly infection and fever.

The army halted and established a temporary camp. Messengers were dispatched to inform Augustus, and word reached Tiberius, who was then in northern Italy. Tiberius set out at once and made an extraordinary journey at speed to reach his brother, a feat later remembered as remarkable even by Roman standards.

Death of Drusus and the End of the Campaign

When Tiberius arrived, the camp was already steeped in despair. Drusus, aware of his condition, ensured that his brother was received with full military honours and acknowledged as commander. The gesture was later remembered as an example of exemplary familial devotion. Despite this, Drusus’ condition deteriorated rapidly. He developed a fever and, within days of Tiberius’ arrival, died in the camp, thirty days after his fall from the horse.

His death brought the campaign to an abrupt end. The army withdrew fully to the Rhine, and the vision of unlimited expansion into Germania was temporarily halted. For Roman memory, the episode marked a decisive turning point: the loss of a commander still in his twenties, at the height of success, whose ambitions had carried Roman arms farther north than ever before.

Drusus’ Death and the Return to Rome

Drusus died after the riding accident that crushed his leg, a wound that ancient medical writers already understood could be fatal. With no way to know the precise mechanism–whether fever, shock, or complications following the fracture–his death stunned the army, which had seen him as vigorous and still in his prime. Tiberius took control at once and organised the recovery and transport of the body, maintaining strict discipline in a camp thrown into grief.

The journey back became a public event on an imperial scale. Drusus’ body was carried from the summer camp to the Rhine, then borne by stages toward Italy and Rome, with communities along the route turning out to mourn and honour him. Augustus and Livia met the cortège as it entered Italy, and the return to the capital was treated as a state occasion, culminating in formal rites in Rome and a public farewell.

Drusus was cremated, and his ashes were placed in the Mausoleum of Augustus, securing his place within the ruling family’s sacred memory.

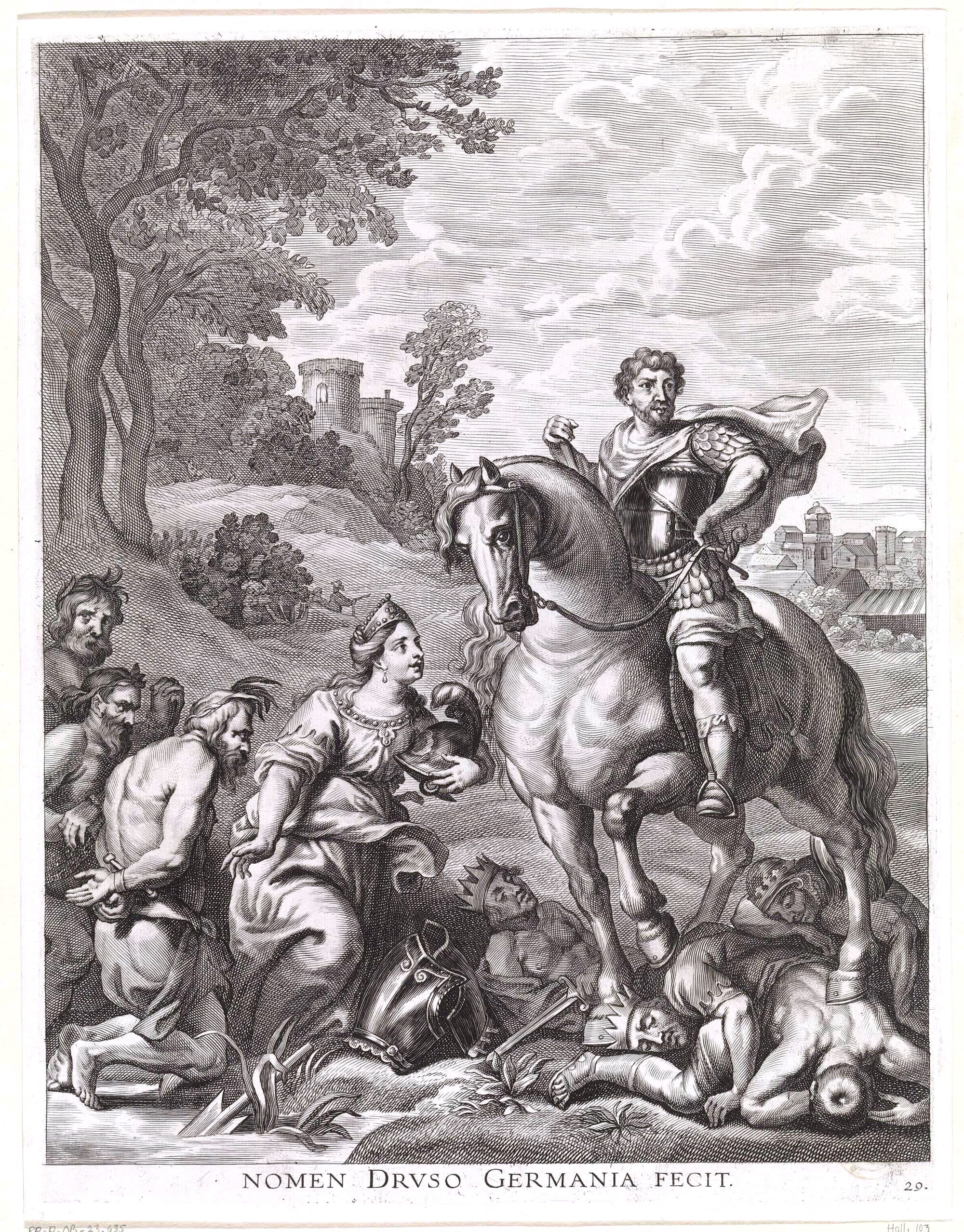

In the aftermath, Drusus’ death was rapidly shaped into a political and dynastic landmark. The Senate voted posthumous honours that fixed his image as Rome’s heroic conqueror in Germania, including monuments and the hereditary title Germanicus for his line. His reputation was cultivated as an ideal of youthful virtue and military excellence, invoked by his family and later emperors as a source of legitimacy.

Rumours of foul play circulated, but the public honours, Augustus’ evident attachment to him, and the sustained effort to memorialise him reveal a different emphasis: He was mourned as an irreplaceable loss–and preserved as a model the regime wanted Rome to remember. ("Eager for Glory. The Untold Story of Drusus the Elder, Conqueror of Germania" by Lindsay Powell)

Drusus did not live long enough to see the consequences of his campaigns. Within a generation, Roman ambitions beyond the Rhine would end in catastrophe, and Germania would be recast as a land unconquerable by arms alone. Yet it was Drusus who came closest to altering that outcome. His roads, forts, alliances, and exploratory campaigns transformed Rome’s understanding of the northern world and reshaped the frontier that followed. Remembered by his contemporaries as a model of youthful virtus and by later rulers as a source of dynastic legitimacy, Drusus remains a figure defined as much by what he achieved as by what his early death prevented Rome from becoming.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: