Delving into the Details of the Gallic Wars of Julius Caesar

The Gallic Wars, a series of military campaigns waged by Gaius Julius Caesar between 58 and 50 BCE, stand as a critical chapter in both Roman and European history.

Eight years of relentless conflict saw the Roman Republic extend its control over Gaul, a vast and diverse region inhabited by fiercely independent tribes. More than a conquest, the Gallic Wars became a showcase of Caesar’s military genius, his political ambition, and his ability to manipulate alliances and rivalries to Rome’s advantage.

Yet, the story of the Gallic Wars is not merely one of Roman dominance—it is also a demonstration of the resilience, culture, and eventual downfall of the Gallic peoples. Through bloody battles, shifting allegiances, and strategic brilliance, these campaigns reshaped the power dynamics of the ancient world and set the stage for the end of the Roman Republic.

Julian in Gaul: A Region Always in War

Before venturing into the past, we travel forward in time, to underline how Gallia has continuously being the target of Roman military through the ages, even when the Roman Empire was close to its demise.

Between 356 and 361, Julian conducted six military campaigns on the frontiers of Roman Gaul, four of which were large-scale operations, while the final two were more limited. These campaigns were not only important in addressing external threats but also deeply intertwined with internal political dynamics.

As Caesar of the West (before becoming Emperor of Rome), Julian’s military endeavors significantly influenced his relationship with his cousin and superior, Constantius II, who had elevated him to power in 355. This evolving dynamic forms a crucial aspect of Julian’s time in Gaul, but it cannot be separated from the details and strategies of the campaigns themselves, which were designed to counter threats from groups like the Alamanni and the Franks.

The primary narrative of Julian’s campaigns comes from Ammianus Marcellinus’ Res Gestae, an invaluable yet highly partisan source. Ammianus viewed Julian as a heroic figure, often comparing him to Alexander the Great and Achilles. While his account is meticulously detailed and rooted in extensive research, Ammianus’ clear admiration for Julian introduces biases.

For instance, his portrayal of Julian’s conflicts—whether with Constantius II or his appointed officers—always casts Julian in a favorable light. Despite its length and vivid descriptions, Ammianus’ narrative often lacks critical details, particularly in the tactical and strategic aspects of the campaigns. Moreover, Ammianus’ focus shifted to the eastern frontier by 360, leaving gaps in his coverage of Julian’s later Gallic campaigns.

Other sources, though fragmentary and equally biased, provide additional insights. Julian’s Letter to the Athenians, written in 361, offers a firsthand account of his military actions and their underlying motivations. Although not a complete narrative, it gives a unique perspective on what Julian considered key features of the wars.

Libanius’ funeral oration for Julian and remnants of Eunapius’ history—though composed by non-eyewitnesses—preserve unique details, such as the context surrounding Julian’s decisive victory at Strasbourg in 357. Archaeological evidence also sheds light on the broader context of these campaigns, particularly the Roman limes (frontier defenses) and the Alamannic and Frankish worlds beyond the Rhine.

These sources collectively provide a patchwork of perspectives, but their biases and gaps in information pose challenges for historical analysis.

A possible representation of Ammianus Marcellinus, or commonly known as Ammian. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

While Ammianus remains the most comprehensive narrative, his partisanship and omissions must be balanced with evidence from Julian’s writings, other ancient texts, and archaeological findings to form a more nuanced understanding of the campaigns that cemented Julian’s reputation as a military leader; but most importantly, showcase how the region of Gaul has always been the target of Rome’s military might. ("The Gallic Wars of Julian Caesar" by Peter J. Heather, in the "A Companion to Julian the Apostate" edited by Stefan Rebenich & Hans-Ulrich Wiemer)

A Legacy Forged in War

Julius Caesar is arguably the most renowned Roman figure in history. As dictator, he laid the groundwork for the eventual establishment of the Roman Empire under Augustus, his great-nephew. His legacy includes a famous affair with Cleopatra, the introduction of the leap year, and his infamous assassination by those who once supported him.

Yet, before his dictatorship, Caesar achieved one of his most remarkable feats: the rapid conquest of Gaul, a region encompassing modern France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Germany west of the Rhine—a territory of over 300,000 square miles. Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul not only altered the political landscape of Europe but also cemented his place in Roman history.

His expeditions saw him become the first Roman general to cross both the Rhine and the English Channel, exploring territories that were mysterious and feared in his time.

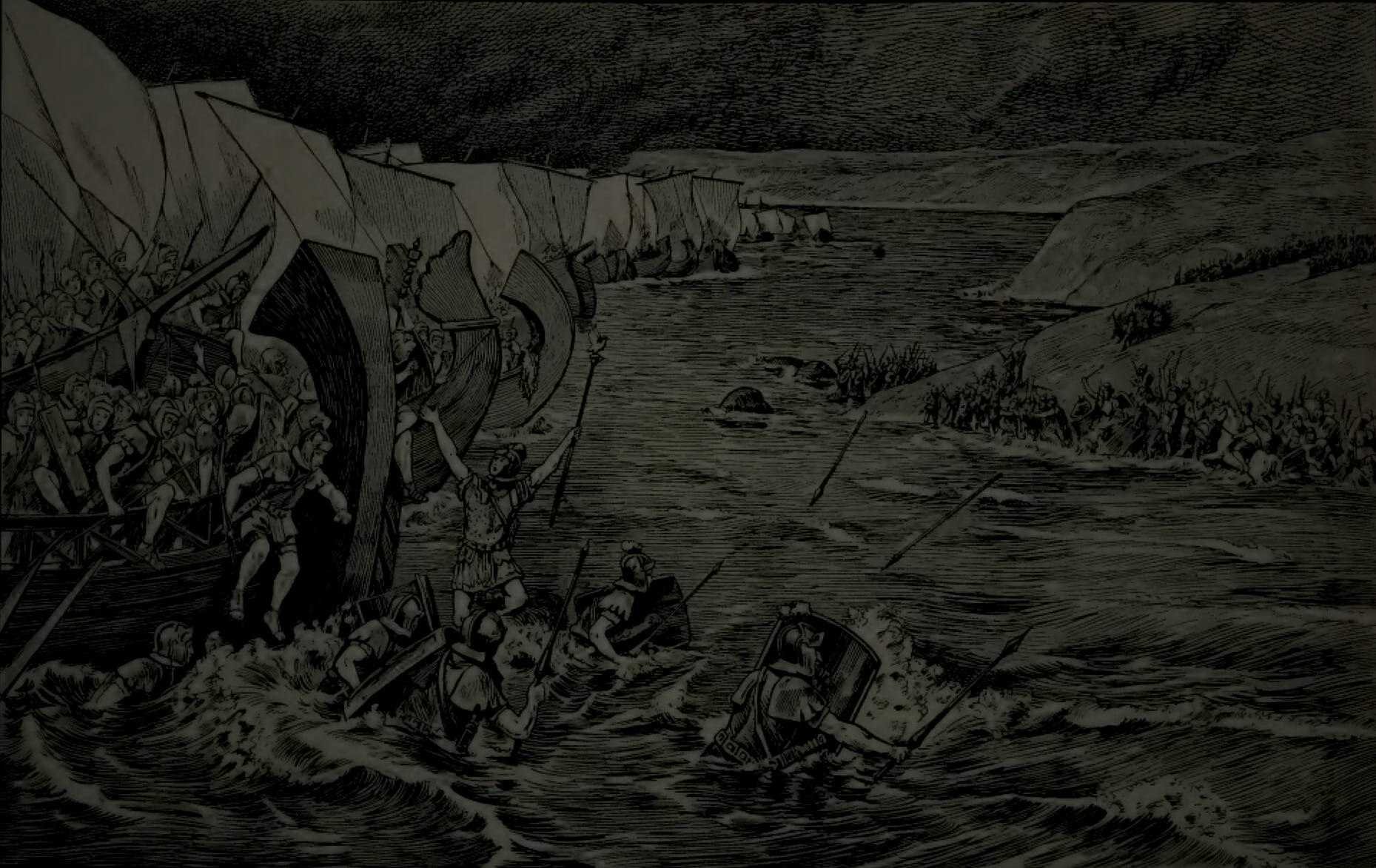

A gravure of Julius Caesar landing in Britain. Public domain

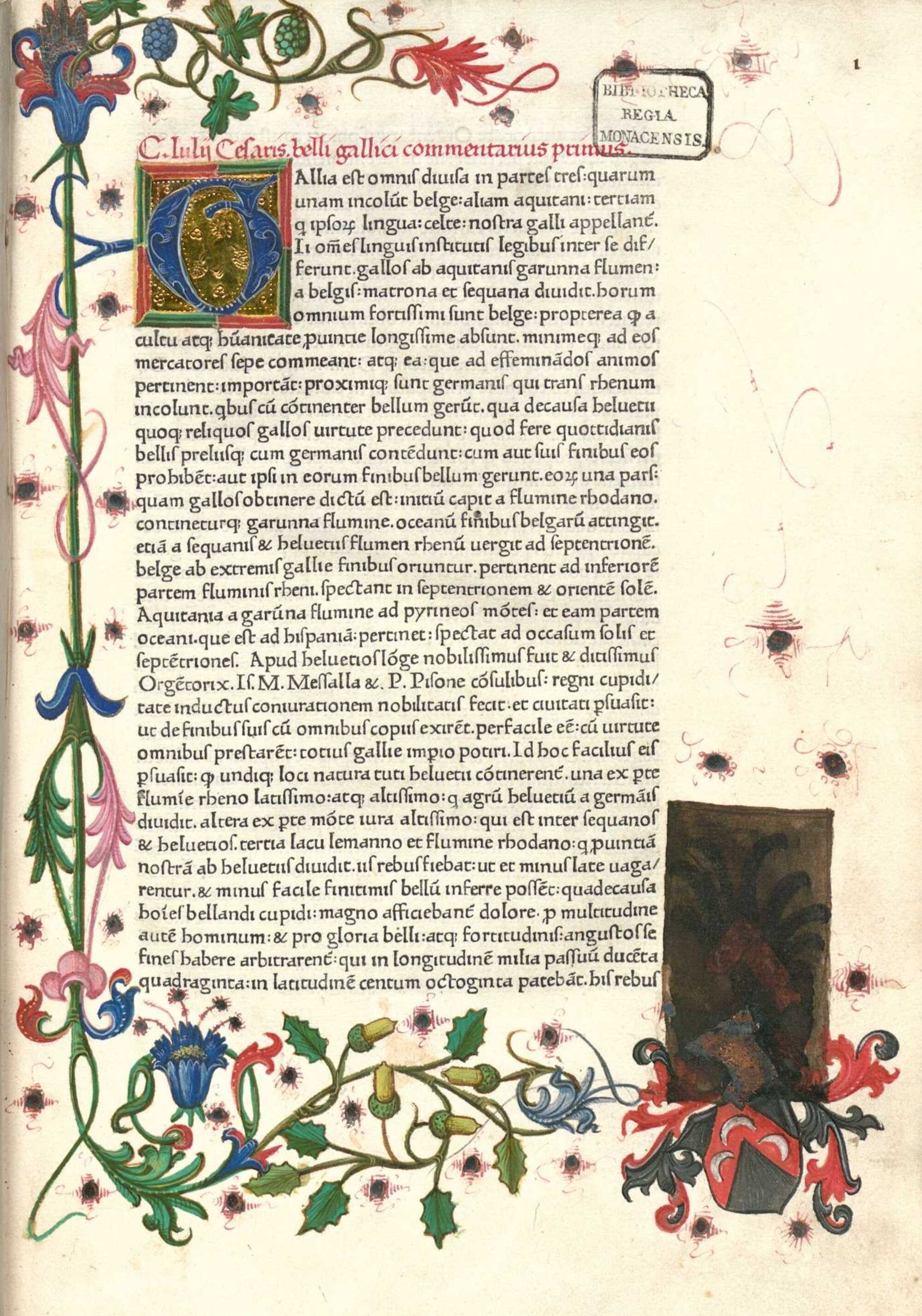

The primary surviving account of these events is Caesar's own Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), an annual record written to keep the Roman populace informed about his victories. However, these commentaries served a dual purpose: they glorified his achievements while downplaying setbacks, making them both an invaluable resource and a piece of self-promotional propaganda.

During the conquest of Gaul, the region was undergoing significant cultural and political transformations. Some tribes were adopting Roman customs and developing urban centers, partly influenced by trade with Rome’s southern provinces. These developments ironically facilitated Rome's conquest, as centralized and wealthier tribes were easier to defeat than their more dispersed counterparts.

Caesar exploited divisions among the Gallic tribes, playing them against one another and securing alliances when beneficial. His disciplined and increasingly experienced legions, along with auxiliary forces from Gaul and Germany, overwhelmed the fragmented resistance.

The conquest was far from seamless. The Gauls staged sporadic uprisings throughout Caesar’s campaigns, culminating in the major rebellion of 52 BCE led by Vercingetorix, who united the tribes in a last-ditch effort to expel the Romans. Employing guerrilla tactics and scorched-earth strategies, the Gauls challenged Caesar’s forces in a brutal war of attrition.

The conflict reached its climax at the siege of Alesia, where Caesar’s engineering skillfulness and military strategy prevailed. Vercingetorix surrendered, and although Gaul would not be fully pacified until Augustus’ reign, the Roman victory was decisive.

Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul not only expanded Rome’s territory but also bolstered his political and military reputation, setting the stage for his eventual rise to power. The Gallic Wars reshaped Europe, paving the way for the transformation of Gaul into Roman provinces and, centuries later, the emergence of modern France. Caesar’s victories, however, came at a cost, leading to unrest in Rome and the civil war that would bring an end to the Republic. (Essential Histories: Caesar's Gallic Wars 58-50 BC, by Kate Gilliver)

The Art of Conquest: Themes and Strategies in Caesar's Gallic War

Paul R. Murphy’s analysis of Caesar’s Gallic War reveals fascinating thematic elements that underscore the strategic and rhetorical brilliance of the Roman general. Caesar’s narrative is not merely a military chronicle but a deliberate construction, combining persuasion (persuasio), shrewdness (calliditas), and Roman virtues (virtus) to justify his campaigns and elevate his leadership.

One notable example from this study is Caesar’s handling of the Helvetii in Book I. Through carefully crafted rhetoric, Caesar portrays the Helvetii as both a dire threat to Roman security and a justification for preemptive action. Murphy highlights Caesar’s statement:

“It is the way of the gods to sometimes allow the wicked to prosper, only so their ultimate downfall can be greater.”

This interpretation aligns with Caesar’s broader strategy of framing his victories as divinely sanctioned and morally righteous, reinforcing his image as a protector of Rome and its allies.

He also emphasizes Caesar’s use of calliditas (shrewdness) as a recurring theme. For example, Caesar outmaneuvered the Helvetii by destroying their supplies and forcing them into a disadvantageous position. By narrating these events, Caesar not only highlights his tactical ingenuity but also contrasts the disciplined, virtuous Roman army with the chaotic and aggressive Gallic tribes.

This juxtaposition underscores the theme of Roman virtus, portraying the Romans as the embodiment of order, courage, and moral superiority. These thematic choices are not incidental but serve a larger purpose in Caesar’s Commentarii. Murphy suggests that the Gallic War was as much about winning hearts and minds in Rome as it was about conquering Gaul.

Caesar’s skillful blending of divine justification, strategic brilliance, and moral virtue created a narrative that celebrated his leadership and bolstered his political ambitions. This perspective adds depth to our understanding of Caesar’s work, revealing it as a masterpiece of persuasion as much as a record of conquest. (Themes of Caesar's "Gallic War", by Paul R. Murphy)

The Mastermind Behind the Gallic Wars and their Narrative

Julius Caesar did not just wage the Gallic Wars on the battlefield; he also created them in writing, shaping the narrative through his Commentarii. As both the architect of the military campaigns and their chronicler, Caesar ensured that vital information was sent back to Rome, likely to strengthen his political position and to use the Commentarii as a tool of propaganda.

In the ruthless world of Roman politics, it was essential to protect oneself, and Caesar excelled at doing so through carefully crafted self-presentation.

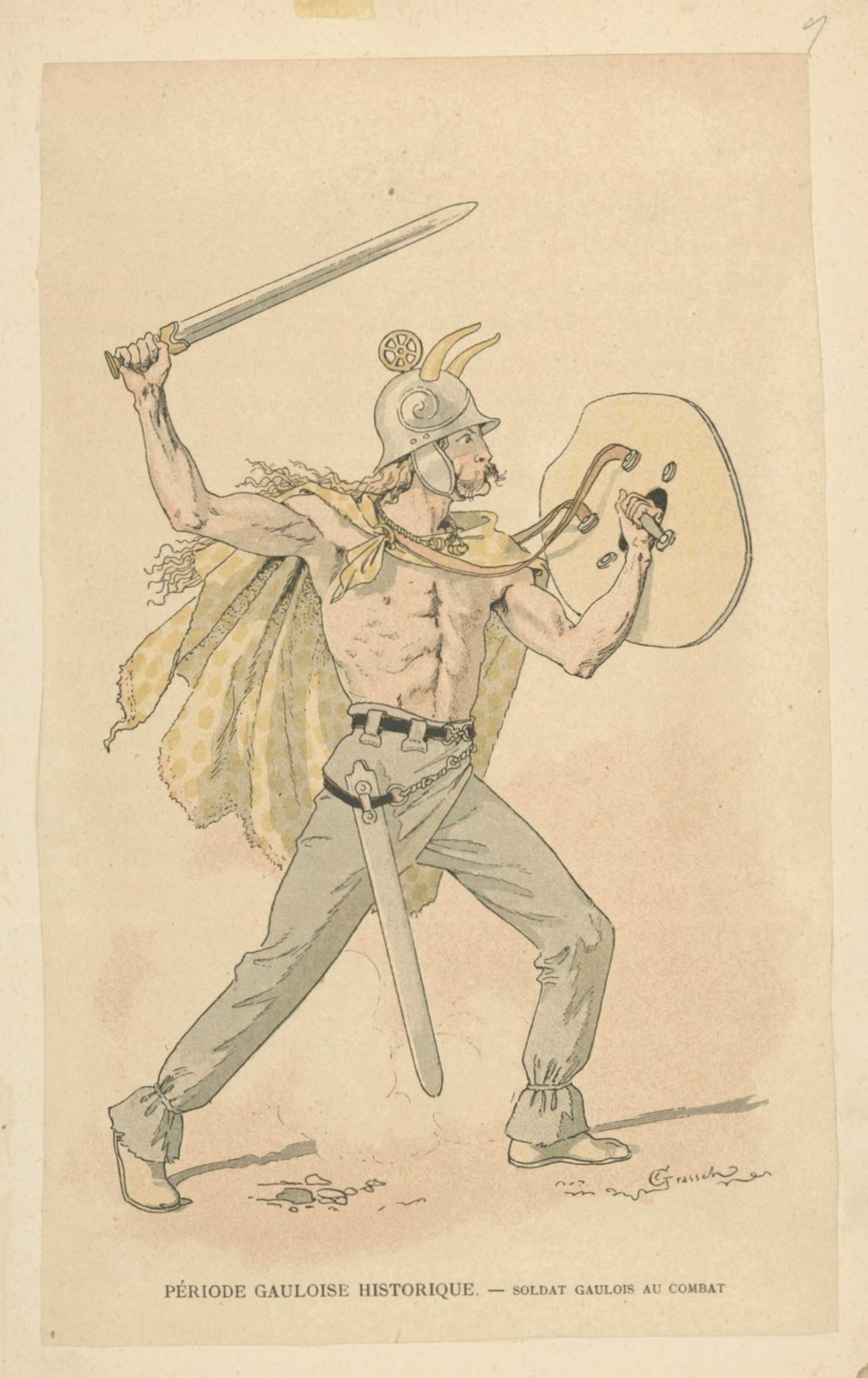

The Ludovisi Gaul, a statue commissioned by Caesar depicting a Gallic man plunging a sword into his own chest, while holding his dead wife. Credits: Stephen Chappell, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Contemporaries and later historians unanimously praised Caesar's literary style. Cicero, in his Brutus (46 BCE), admired Caesar's oratory, noting his straightforward yet compelling delivery. Sallust considered Caesar an intelligent and skilled speaker, while Quintilian, writing in the first century CE, described Caesar as a fiery orator with exceptional energy.

Tacitus, known for his sharp criticism, admitted that Caesar’s speeches were competent, though not extraordinary, but conceded that Caesar’s brilliance shone elsewhere. Pliny the Younger ranked Caesar among the finest orators, and Plutarch remarked that Caesar could have achieved greatness in oratory had he not prioritized politics. Even Suetonius, known for his gossip-laden accounts, and Apuleius, writing later, commended Caesar’s unique warmth and brilliance as a communicator.

The Commentaries on the Gallic War represent a different kind of literary achievement. While oratory demands rhetorical flair, Caesar's Commentarii are notable for their clear and concise style, reflecting an older Roman tradition of historical writing.

Cicero acknowledged this tradition in De Oratore (55 BCE), linking Caesar’s work to the annales-commentarii genre of Roman historiography. Caesar’s general, Hirtius, admitted his own lack of elegance compared to Caesar's polished writing, praising the speed and precision with which the Commentarii were composed. Suetonius echoed this admiration, highlighting Caesar’s breadth of knowledge, efficient use of resources, and innovative techniques, such as the use of ciphers.

Ultimately, Caesar’s Commentarii stand as a proof to his mastery of both strategy and style. Written while actively campaigning in Gaul, these works provide not just a firsthand account of the Gallic Wars but also a carefully curated narrative that immortalizes Caesar’s accomplishments.

Dictating Greatness: Julius Caesar and the Role of Scribes in the Gallic Wars

The creation of Caesar’s Commentarii raises two important questions: who crafted the narrative, and who physically put the words onto the page? While Caesar himself shaped the content and decided what he wanted to convey, the actual writing process relied heavily on the work of scribes. As a general constantly engaged in action, Caesar had little time for the act of writing. He described his responsibilities during battle in The Gallic War:

"All things had to be done at one time by Caesar: the banner had to be displayed, which was evident, when it was fitting to engage at arms; the signal had to be given by the trumpet; the soldiers had to be recalled from their work; those who had gone a little farther for the sake of seeking [items for the] the ramparts had to be summoned; the battle line had to be drawn up; the soldiers had to be encouraged; the signal had to be given."

The responsibility of writing fell to scribes, often attached to the Quaestor’s staff. Plutarch provides a vivid image of Caesar’s working habits, noting that he dictated constantly, even while traveling:

"Most of his sleep, at least, he got in cars or litters, making his rest conducive to action, and in the day-time he would have himself conveyed to garrisons, cities, or camps; one slave who was accustomed to write from dictation as he travelled sitting by his side, and one soldier standing behind him with a sword."

Plutarch, Life of Caesar

Pliny the Elder was similarly astonished by Caesar’s extraordinary mental capacity and multitasking abilities, highlighting his unique efficiency in Natural History:

"The most remarkable instance, I think, of vigour of mind in any man ever born, was that of Caesar, the Dictator.

I am not at present alluding to his valour and courage, nor yet his exalted genius, which was capable of embracing everything under the face of heaven, but I am speaking of that innate vigour of mind, which was so peculiar to him, and that promptness which seemed to act like a flash of lightning.

We find it stated that he was able to write or read, and, at the same time, to dictate and listen.

He could dictate to his secretaries four letters at once, and those on the most important business; and, indeed, if he was busy about nothing else, as many as seven."

These descriptions not only confirm Caesar’s reliance on scribes but also emphasize the efficiency with which his ideas were recorded. The scribes who served him might have been slaves or young men seeking political advancement by attaching themselves to his retinue. Through their work, his thoughts and strategies were transformed into written narratives that immortalized his campaigns.

The Commentarii, thus, are not only a evidence of Caesar’s strategic brilliance but also to the indispensable role of his scribes, who ensured that his words and deeds were meticulously preserved, even in the midst of war. (Who Wrote the Gallic Wars?, by Ruth L. Breindel)

Calculated Ambition and the Gallic Wars

Jesse Fokke, in his newly released novel The Boar and the Eagle, sheds light on Julius Caesar’s calculated maneuvers during the Gallic Wars, providing a fresh perspective on his political and military strategies. Fokke portrays Caesar as a leader who used the Gallic Wars not merely as a campaign of conquest but as a carefully orchestrated platform to secure his political ambitions and circumvent the constraints imposed by the Roman Senate.

One compelling example Fokke highlights is Caesar’s decision to recruit unauthorized legions in Gallia Cisalpina, a move that underscored his audacity and strategic foresight. He narrates:

...Many gasped at this, and there were some furious whispers here and there. “Did the Senate sanction this, Gaius Julius?” Sulpicius Rufus asked. “I’m only asking out of curiosity.”

“The Senate has granted me the authority to do what’s necessary to serve Rome’s interests, Servius Sulpicius.”

“I see, thank you Gaius Julius.”

That means the Senate did not sanction it, Crassus decided, with mounting amazement and concern. It was the prerogative of the Senate to order the recruitment of legions, so Caesar had overstepped his bounds as a magistrate. Moreover, he said he’d raised the legions in Gallia Cisalpina…

“May I ask in which part of Gallia Cisalpina you’ve raised these legions, Gaius Julius?” Crassus asked hesitantly.

“Certainly,” Caesar said, not at all put out by the obvious shock among his officers. Clearly, he had expected it.

“The legions were recruited on both sides of the Padus.”

An answer Crassus half expected but fully dreaded. Gallia Cisalpina was an odd province, divided into two parts, Gallia Cispadana—“Gaul on This Side of the Padus”—and Gallia Transpadana—“Gaul on the Other Side of the Padus,” the Padus river cutting the province in two.

The province of Gallia Cisalpina had been so thoroughly Romanized that it was seen by many as simply a part of Italy, and most of the inhabitants themselves definitely saw it that way too. The population of Gallia Cispadana had been granted Roman citizenship thirty years ago, but Gallia Transpadana, that part which lay on the side of the Padus river farthest from Rome, hadn’t for some reason. That meant that even if the Senate had given Caesar permission to raise legions, he couldn’t have possibly raised them in Gallia Transpadana, as only Roman citizens were allowed to become legionaries. The whole thing was illegal in each and every way.

“But Gaius Julius, won’t this put you in legal jeopardy?” asked Servius Sulpicius.

Caesar only looked amused at this. “Ahhh. Like father, like son,” he said, folding his hands together. “All the Sulpicii Rufi are born and bred for the courts. I am certain the Senate will see that this was the right call when those legions are put to good use. I will ensure that they will earn their keep and more, and besides, by the time I will lose my imperium and become liable for prosecution, Gallia Cisalpina will already be a part of Italy. It will be a done deal.”

Fokke’s narrative emphasizes Caesar’s ability to view military campaigns as extensions of his political strategy. By combining military power and demonstrating his leadership through the conquests in Gaul, Caesar built a foundation for his eventual rise to dictator. He masterfully played the dual role of general and statesman, ensuring that his victories resonated not only on the battlefield but also in the political arena of Rome.

Through vivid storytelling and meticulous research, The Boar and the Eagle brings to life the complicated layers of Caesar’s ambitions, showing how his strategic brilliance during the Gallic Wars reshaped the trajectory of Roman history.

Reconstructing Time: Chronology Challenges in Caesar’s Gallic War

In the 19th and 20th centuries, German scholars produced detailed commentaries on Caesar's Civil War and Gallic War. While the Civil War received precise chronological tables due to abundant time markers and corroborating evidence, such as Cicero's letters, the Gallic War lacked such detailed dating. Caesar’s narrative and Hirtius’ eighth book of the Gallic War provide only a few fixed dates, leaving scholars to rely on temporal clues, such as seasonal references and estimates of travel and march durations.

Past efforts to construct a chronology of the Gallic War were broad, assigning events to general seasons. However, there exists a study that suggests, that a more precise chronology is possible by leveraging modern tools like GIS-based maps, Cicero’s correspondence, and calculations of marching speeds. By reanalyzing these data sources, a narrower and more accurate timeline for Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul can be developed, improving upon earlier, less precise reconstructions.

Climate Conditions

The Gallic War coincided with a warming period in central Europe, leading to glacier retreat and allowing for earlier crossings of Alpine passes. Caesar likely crossed the Alps by early May, taking the most direct route without significant detours.

Distances and Terrain

Distances were measured using Roman roads from the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. However, since Roman roads were not yet built in independent Gaul, pre-Roman routes were less direct, especially in rugged terrain.

Adjustments to distances were made, increasing them by 25% to account for less efficient roads outside Roman provinces. Roman road distances in provinces like Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul were considered reliable.

Time Requirements for Sieges and Town Surrenders

A formal siege (constructing ramps, towers, etc.) typically required a minimum of two days, while surrender procedures (collecting hostages, resupplying the army, etc.) also took at least two days unless Caesar specified urgency. In some cases, towns were attacked immediately upon the army’s arrival.

Chronological Estimates

Precise dates for events in the Gallic War are rare, with most based on reasonable calculations. Fixed dates are occasionally derived from Caesar’s references to moon phases or equinoxes.

The reconstructed chronology uses the Roman civil calendar, adjusting for discrepancies with the Julian calendar, which became significant only after the wars due to political disorder.

Traveling and Marching Speeds

Caesar’s accounts, along with other sources, provide insights into the time it took to traverse specific distances. The data highlight instances of rapid movements, aiding in reconstructing campaign timelines.

Caesar’s Marches: Logistics and Tactical Movements

Caesar’s own accounts provide invaluable information about the distances and speeds of Roman military marches during the Gallic Wars. He frequently used the term “a day’s normal march,” which he defined as approximately 16 Roman miles (15 modern miles or 24 kilometers), covered in around five hours.

Hirtius also referred to standard daily marches but did not specify their length. In 57 BCE, Caesar traveled from Vesontio (modern Besançon) to the Matrona (likely near modern Épernay) in 15 days. Depending on whether he paused for rest, his army’s average daily distance varied from 20 km (12.4 mi) without stops to 23 km (14.3 mi) with two rest days.

When urgency demanded, Caesar’s forces significantly increased their pace. For example, during the same year, he conducted a forced march of approximately 62.5 km (39 mi), augmented for rugged terrain, from the battle site at the Axona (near Berry-au-Bac) to Noviodunum (near Soissons). He attacked the town immediately upon arrival but failed to capture it.

Another notable example occurred in late fall of 54 BCE, when Quintus Cicero’s winter camp was under siege by the Nervii and their allies. Caesar sent a mounted messenger in the late afternoon from Samarobriva (modern Amiens) to his quaestor Marcus Crassus, whose camp was 37 km (23 mi) away.

Crassus mobilized his legion and traveled through the night, reaching Caesar in 8–9 hours, covering roughly 4.4 km (2.7 mi) per hour with a fully encumbered legion and baggage train. Caesar himself set out later that morning, covering an additional 30 km (18.5 mi) that day.

In a striking demonstration of speed and endurance, Caesar left his camp at Gergovia in June 52 BCE with lightly equipped legions (legiones expeditae), covering 46.25 mi (74 km) in 24 hours, including a three-hour rest period. His forces engaged the Aeduan rebels in a peaceful confrontation and returned to camp before sunrise.

In another instance, in May 58 BCE, Caesar led five legions from Ocelum, near the Mt. Genèvre Pass, to the Vocontii territory. Despite opposition from mountain tribes, the legions traversed an estimated 195 km (122 mi) over seven days, averaging 28 km (17.5 mi) per day. In this mountainous terrain, the army likely traveled with pack animals rather than wagons.

These examples highlight the remarkable discipline and logistical efficiency of Caesar’s forces, proving their ability to adapt to varying terrain, weather, and tactical urgency, often achieving extraordinary feats of endurance and speed. ("Reconstructing the chronology of Caesar's Gallic Wars" by Kurt A. Raaflaub and John T. Ramsey)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: