Ammian, or Ammianus Marcellinus: From a Roman Soldier to one of the Best Historians of all time

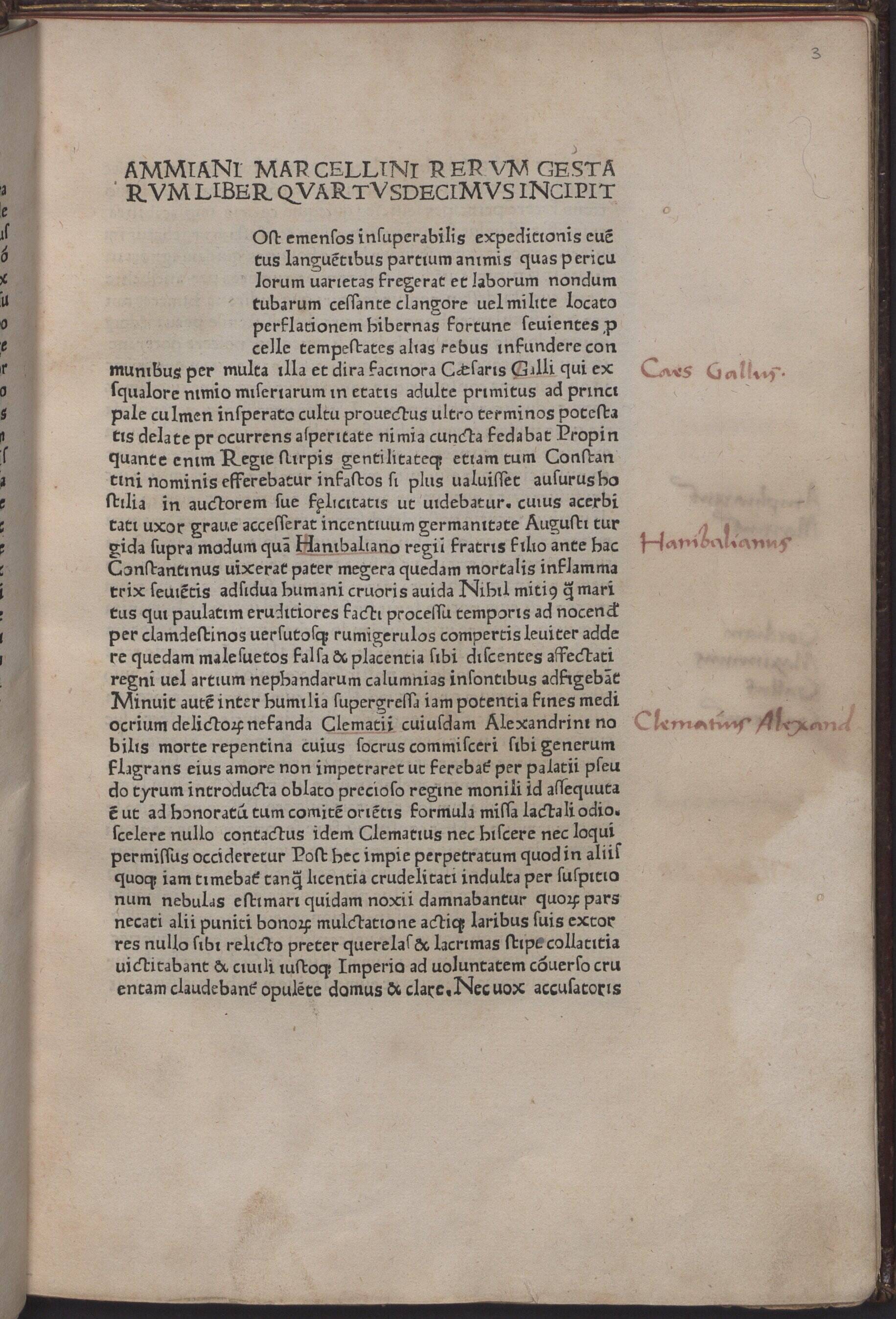

Ammianus Marcellinus wrote what is known as Res gestae, the ultimate historical account about the Roman Empire, that has survived to our days.

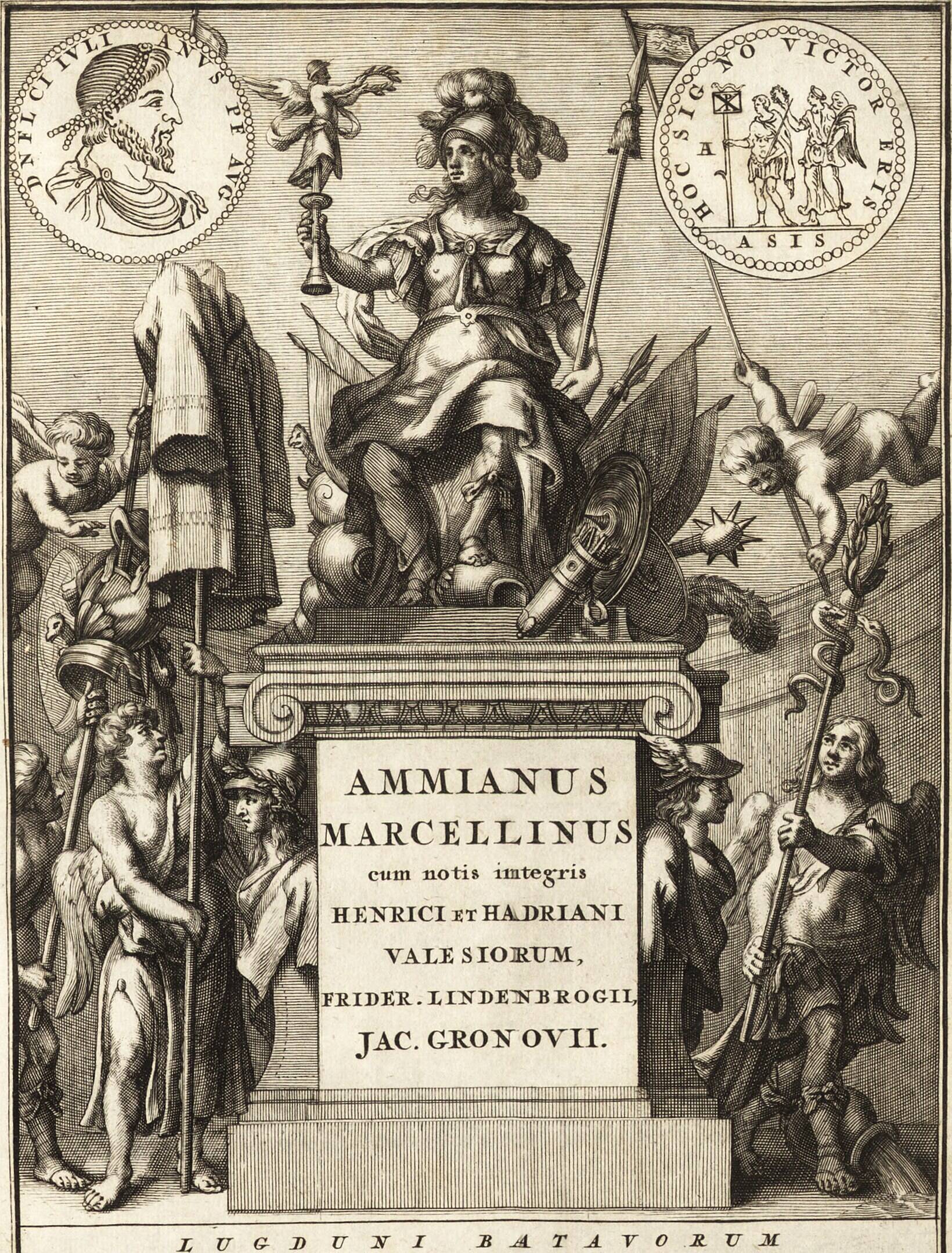

Ammianus Marcellinus is often considered the last great Roman historian, continuing the tradition of historians like Tacitus. His narrative style and critical approach are seen as a bridge between the classical and medieval historiographical traditions.

Who was Ammianus Marcellinus?

Born into a noble Greek family in Antioch, Ammianus Marcellinus served in military campaigns against the Persians under the emperors Julian and Jovian. After his military career, he settled in Rome and published "The Chronicles of Events," a continuation of Tacitus' histories, which detailed the history of the Roman Empire from the accession of Nerva to the death of Valens.

He calls himself Graecus which means Greek. His native language is unknown, but he probably spoke Greek and Latin. The surviving books of his history cover the years 353 to 378. His frequent pride in his Hellenic education and heritage did not stop him from showing an equally enthusiastic admiration for Latin authors and a strong patriotic allegiance to Rome.

He also demonstrated his political devotion through respect for state traditions and personal military service during the mid-century. Therefore, it is particularly fitting that this man, who was deeply loyal to both his local and imperial roots and immersed in both Latin and Greek culture, chose to write the last great history of Roman affairs. (Ammianus Marcellinus as a military historian, Gurry Allen Grump, University of Illinois.)

A native of Antioch, Ammianus Marcellinus was a soldier and a member of the prefectores domestici, the emperor's bodyguard, which admitted only men of noble birth. He served on the staff of Ursicinus —a high-ranking Roman military officer, serving as Magister Equitum per Orientem (Master of Horse of the East) and later as Magister Peditum Praesentalis around 349–359 AD in the late Roman Empire, a citizen of Antioch with strong connections in the Eastern Roman Empire— accompanying him on various expeditions, and participated in Julian's campaigns against the Persians.

After this period, Ammianus never mentions himself, leaving the details of when he left the military and retired to Rome, where he wrote his History, unknown. His birth and death dates are also unclear, though some passages suggest he lived nearly to the end of the fourth century. It is uncertain whether he was a Christian or a Pagan, but it is generally believed that he adhered to the ancient Roman religion while maintaining a respectful tone towards Christians and Christianity. (The Roman History of Ammianus Marcellinus, translated by C.D. Yonge, M.A)

Ammianus entered the Roman army as an officer in an elite corps around 350 AD and first appears in his narrative in the year 354. The duration of his service beyond 359 is unclear, as he disappears from his narrative after escaping the storming of Amida by the Persian king and safely returning to Antioch. Ammianus reappears in his narrative in 363, indicated by his use of the first-person plural, suggesting he joined Julian's expedition into Persia at Circesium. He then returned to Antioch with the defeated Roman army after its failure.

Afterward, Ammianus traveled in Greece, where he witnessed a ship being carried nearly two miles inland near Mothone in Laconia by the tsunami on 21 July 365. He also observed at least part of the coasts of Thrace and the Black Sea and likely traversed the Balkans, where he saw the remains of Romans and Goths who had perished in battles near Marcianople in the autumn of 377. He also went to Egypt before returning to Rome, touring the country during his stay.

Although Greek, Ammianus wrote his extensive history in Latin, covering nearly three centuries, from Emperor Nerva's accession in 96 to the immediate aftermath of the disastrous Battle of Adrianople on 9 August 378, likely in a total of thirty-six books. Only the second half of the Res Gestae has survived, starting in the middle of the historian's account of the two emperors' activities during the 353 campaign season, spanning six hundred pages in modern critical editions.

It is the most comprehensive, precise, and reliable narrative source for military campaigns and political events at the imperial court in the fourth century. Consequently, Ammianus' work forms the foundation for all modern narrative accounts of the period from 353 to 378. (Ammianus Marcellinus and the Representation of Historical Reality by Timothy David Barnes)

“At the time when Rome first began to rise into a position of world-wide splendour, in order that she might grow to a towering stature, Virtue and Fortune, ordinarily at variance, formed a pact of eternal peace; for if either one of them had failed her, Rome had not come to complete supremacy.

Her people, from the very cradle to the end of their childhood, a period of about three hundred years, carried on wars about her walls. Then, entering adult life, after many toilsome wars, they crossed the Alps and the sea. Grown to youth and manhood, from every region which the vast globe includes, they brought back laurels and triumphs. And now, declining into old age, and often owing victory to its name alone, it has come to a quieter period of life.

Thus the venerable city, after humbling the proud necks of savage nations, and making laws, the everlasting foundations and moorings of liberty, like a thrifty parent, wise and wealthy, has entrusted the management of her inheritance to the Caesars, as to her children.

And although for some time the tribes have been inactive and the centuriesmat peace, and there are no contests for votes but the tranquility of Numa's time has returned, yet throughout all regions and parts of the earth she is accepted as mistress and queen; everywhere the white hair of the senators and their authority are revered and the name of the Roman people is respected and honoured.”

Ammianus Marcellinus, Book XIV, 6.3. The faults of the Roman Senate and People.

Ammianus Marcellinus’ work

Around 385, Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote "Res Gestae Libri XXI," the last major surviving historical account of the late Roman Empire. His work detailed the history of Rome from 96 to 378, though only the sections covering the years 353 to 378 have survived.

“This is the history of events from the reign of the emperor Nerva to the death of Valens, which I, a former soldier and a Greek (miles quondam et Graecus), have composed to the best of my ability. It claims to be the truth, which I have never ventured to pervert either by silence or a lie.”

(Amm. Marc. 31.16.9)

Professor Ramsay (in Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography) says,

"We are indebted to him for a knowledge of many important facts not elsewhere recorded, and for much valuable insight into the modes of thought and the general tone of public feeling prevalent in his day. Nearly all the statements admitted appear to be founded upon his own observations, or upon the information derived from trustworthy eye-witnesses.

A considerable number of dissertations and digressions are introduced, many of them highly interesting and valuable. Such are his notices of the institutions and manners of the Saracens, of the Scythians and Sarmatians, the Huns and Alani, the Egyptians and their country, and his geographical discussions upon Gaul, the Pontus, and Thrace.

Less legitimate and less judicious are his geological speculations upon earthquakes, his astronomical inquiries into eclipses, comets, and the regulation of the calendar; his medical researches into the origin of epidemics; his zoological theory on the destruction of lions by mosquitos, and his horticultural essay on the impregnation of palms.

In addition to industry in research and honesty of purpose, he was gifted with a large measure of strong common sense, which enabled him in many points to rise superior to the prejudices of his day, and with a clear-sighted independence of spirit which prevented him from being dazzled or over-awed by the brilliancy and the terrors which enveloped the imperial throne.

But although sufficiently acute in detecting and exposing the follies of others, and especially in ridiculing the absurdities of popular superstition, Ammianus did not entirely escape the contagion. The general and deep-seated belief in magic spells, omens, prodigies, and oracles, which appears to have gained additional strength upon the first introduction of Christianity, evidently exercised no small influence over his mind.

The old legends and doctrines of the pagan creed, and the subtle mysticism which philosophers pretended to discover lurking below, when mixed up with the pure and simple but startling tenets of the new faith, formed a confused mass which few intellects could reduce to order and harmony."

Gurry Allen Grump in his thesis Ammianus Marcellinus as a military historian states that Ammianus, devoted more space to warfare than his major Latin predecessors, Livy and Tacitus. While he occasionally focused on the affairs of Rome, the curiosities of the vast empire, and the details of Roman civil administration, his pages were predominantly filled with the march of armies, the whir of siege engines, and the chaos of battles.

Ammianus seems to have placed such heavy emphasis on combat, that any thorough evaluation of his merits as a historian must first consider his talent, in describing warfare.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: