Credit, Loans, and Risk: How Ancient Rome Handled Money Without a Central Bank

The Roman Empire thrived without a central bank or paper currency. Yet its financial system—powered by deposit bankers, local lenders, and legal frameworks—channeled credit across classes and continents. Here’s why Rome’s bankers deserve a seat in the modern history of finance.

They didn’t have paper bills or a central bank—but Rome ran on credit. Beneath the grandeur of forums and military conquests lay a humming financial world of bankers, brokers, and books of account. From the bustling stalls of the Forum Romanum to the private chambers of aristocratic villas, Roman banking shaped trade, fueled construction, and underwrote the ambitions of senators and merchants alike.

With no vaults as we know them, trust and reputation were the true currency of Roman finance—an economy built on silver, ink, and the weight of one’s word.

How Rome Handled Credit

When we speak of “banking and business” in the Roman world, we refer to financial activities centered on money itself—distinct from trade, which deals in goods. Money in Rome served not only as a unit of account, a medium of exchange, and a store of value, but also rapidly emerged as a reference point for both personal wealth and broader economic interaction.

Although much of Roman society still operated within a non-monetized framework, this sector could no longer be viewed in isolation. Its existence was increasingly defined by its relationship to the growing dominance of monetary exchange.

Unlike later historical periods—such as the Middle Ages or early modern Europe—Rome did not employ financial instruments like bills of exchange. Coins were the sole structured monetary tool available, and while Romans did not always pay in physical coin, all systems of value and trust ultimately relied on them.

The circulation of money among private individuals reshaped the social order, acting both as a source of division and as a common medium that symbolized political and communal unity, owing to the state's exclusive right to mint currency. In ancient Rome, lending at interest was a routine, even respectable activity among members of the elite.

Many senators and equestrians actively issued loans, often without concealing their creditor status.

A possible representation of a Roman senator lending money to another Roman noble. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

Yet, this should not be confused with professional banking. The term “banking” in the Roman context applies specifically to professionals—argentarii, coactores argentarii, and later nummularii—who took deposits and lent out money not just from their own funds but also from client holdings. These men maintained accounts (rationes), a legal right reserved to registered bankers under Roman law.

The distinction between elite lenders like Crassus or Atticus and professional bankers is critical. Unlike aristocrats who dabbled in finance without regulatory constraints, professional bankers were tradesmen governed by guild-like rules, trained by apprenticeship, and tied to fixed premises and working hours. They operated at a different level—economically, legally, and symbolically.

Who were the Bankers of the Roman Empire?

Roman financial society was thus stratified:

- Elite financiers treated money as an extension of their estates, a means to preserve or augment their patrimony.

- Professional bankers, on the other hand, treated it as capital.

- Between these two poles stood a third group—entrepreneurs—whose approach to money was perhaps the most modern. They were willing to risk significant investment for future gain, even if only to ultimately secure a larger patrimony.

This divide between elite wealth and professional finance recurs across many pre-industrial societies. While in some periods tradesmen influenced political life, in others they remained firmly under aristocratic dominance.

The Roman case invites comparison not just with the Middle Ages but also with the economic shifts that would later lead to industrialization. Confusing elite moneylenders with true bankers risks blurring essential distinctions in economic and social function.

The Roman state, of course, played its part. It minted currency (a notable example is Domitian’s reforms), regulated trades, and engaged in large-scale financial ventures—from leasing public lands to managing army provisions and tax farming. Still, most economic activity remained private.

Although the elite profited immensely from their public and military roles, much of their income stemmed from inherited estates and investment.

A possible representation of a Roman noble’s villa interior. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

This exploration of Roman finance fits within a broader scholarly debate on the nature of ancient economies. Were they fundamentally “modern” in structure but stunted by external forces? Or were they limited by internal constraints, inherently “primitive” in economic potential?

Whether comparing Rome’s economy with medieval systems or evaluating its role in long-term historical development, one thing remains clear: understanding Roman banking requires a careful, comparative, and conceptually precise approach.

Rome’s Banking Professions

The origins of professional banking in the ancient world can be traced to fifth-century BCE Athens with the trapezites, but similar figures—argentarii—appeared in Rome by the early third century BCE. Far from being Greek imports, these Roman bankers were homegrown professionals, offering a range of services from money-changing and coin assaying to deposit handling and credit.

The term argentarius had nothing to do with silversmithing in its original context—only centuries later did that semantic shift occur, reflecting the profession’s decline and transformation. Over time, Rome’s banking landscape diversified. Alongside the argentarii, we find the nummularii—originally coin testers who later became deposit bankers—and the coactores, or money receivers.

A hybrid type, the coactores argentarii, emerged during the late Republic, handling both banking and collection services. While no women held official status as bankers, regional differences are apparent across the Empire. In Egypt, both public and private banks thrived, while in Palestine, money-changing was tied closely to the Temple tax system.

Rome’s early banking system reached a high point in the late Republic and early Principate, with bankers deeply involved in auctions and credit operations. However, by the third century CE, cracks began to show.

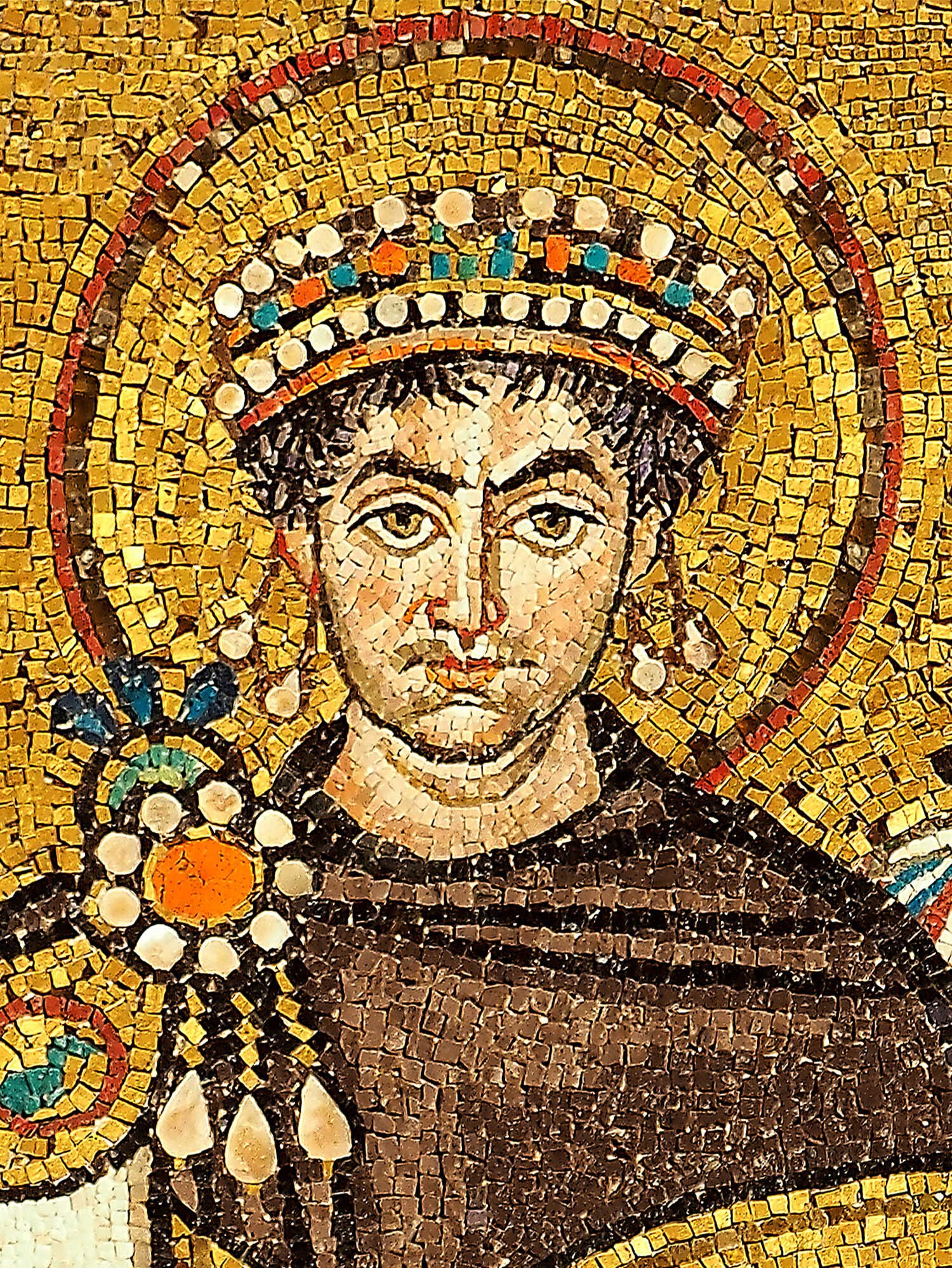

Inflation, coin devaluation, and shifting economic patterns led to a sharp decline in professional banking activity—especially in the Latin-speaking West. The term argentarius faded from inscriptions and only reemerged, confusingly, to describe silversmiths. It was only in later centuries, notably during Justinian’s reign, that these trades began to converge again.

Bankers operated at the grassroots level of society. Most were freedmen or plebeians, legally barred from the Senate and equestrian order. Yet a few, like the ancestors of Horace and Vespasian, rose through the ranks. These men did not deal in aristocratic wealth management; they were practical financiers, running workshops, maintaining ledgers, and navigating legal obligations.

Their client registers (rationes) were legally admissible documents in court, and they engaged in a range of financial practices—from sealed deposits and short-term loans to payment services and third-party guarantees (receptum argentarii). Despite their limited social status, these bankers democratized access to credit. Unlike elite lenders, they brought banking services to ordinary citizens, provincial towns, and urban markets.

While modern historians debate whether ancient banking was “primitive” or “proto-modern,” the Roman system shows a nuanced middle ground. It was flexible, sophisticated, and integral to both everyday commerce and imperial scale operations—even if it never quite developed the institutional depth of later financial systems.

Elite Credit: Moneylending and Finance Among Rome’s Ruling Classes

From the early Republic through the Imperial period, debt and credit were woven into the political, social, and moral fabric of Roman life. Ancient authors often recounted the unrest caused by widespread debt, especially among plebeians.

Figures like Manlius Capitolinus took up the cause of the indebted poor, distinguishing between the exploitative tactics of moneylenders and the political dominance of the patricians. Though some aristocrats, including senators, extended loans for profit, they were not considered “professional” moneylenders.

Social expectations and obligations prevented members of the elite from devoting themselves to any one economic activity—particularly one associated with profit-seeking. In the fourth century BCE, Rome still lacked minted coinage. Loans were likely made in kind or in bronze bars (aes rude or aes signatum), which functioned as primitive currency.

By the late Republic, however, lending money had become an accepted part of elite wealth management. Cicero’s writings and Plautus’ comedies both reveal how widespread and normalized these transactions were. By the first century BCE, dozens of senators and equestrians had substantial holdings in debt-claims, and the Emperor himself was no stranger to large-scale lending.

Despite this ubiquity, elite lenders were never considered bankers. Their operations were informal and relied on a network of dependants, friends, and intermediaries to assess risk, enforce payments, and manage collections.

Public places like the columna Maenia served as information exchanges for reputations and creditworthiness. The fenerator—a term that came to imply someone engaged exclusively in interest-bearing loans—was not a title aristocrats would claim, even when their actions matched the definition.

These financial dealings ranged from personal loans and investment lending to politically motivated generosity or euergetic gestures. Lending without interest was sometimes a display of social virtue or political strategy, but profit was seldom far from the surface. The boundaries between economic, political, and social interests were fluid, and the motivations of aristocratic financiers often intertwined prestige with pragmatism.

Aristocratic finance, though generally less specialized than professional banking, included a range of complex operations: intermediary lending, transfer of debt claims, and managing the patrimonies of absent senators. Men like Atticus and Cluvius served as trusted chargés d’affaires for others in their rank, without pay but with considerable influence.

These men weren’t bankers, yet they handled loans, monitored estates, and moved substantial sums.

A possible representation of Marcus Cluvius Rufus. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

Importantly, elite moneylenders did not receive sealed or banked deposits in the legal sense. That domain remained exclusive to professional bankers—the argentarii, coactores argentarii, and later the nummularii.

The elite might invest through intermediaries or enter into societas danistaria contracts, but they did not operate accounts or keep client registers as bankers did. Their transactions, though financially significant, lacked the formalized structure of the deposit banking profession. Whether through loans to cities in the provinces, high-risk maritime loans, or debt-transfer arrangements, aristocratic financiers navigated a world in which legal, economic, and social considerations overlapped.

Rome’s ruling class lent extensively but never stepped fully into the role of banker. Their investments, however substantial, were always tethered to their social rank, cultural values, and political ambitions—forming a distinctive system of elite finance that helped sustain both personal wealth and imperial power. (Banking and Business in the Roman World, by Jean Andreau)

Vanished Vaults: The Rise and Fall of Rome’s Deposit Bankers

The Roman Empire once boasted a flourishing system of deposit banking, one sophisticated enough to channel savings from ordinary citizens into productive loans. But sometime after the mid-third century CE, this system disappeared—eerily and abruptly.

What happened to the argentarii, nummularii, and coactores argentarii who once played a vital role in the financial arteries of the Roman economy? And what do their fates reveal about Rome’s unraveling?

Roman coin of Trajan Decius Antoninianus. Credits: nevio3 from Getty Images, by Canva

The mystery of why Rome’s once-thriving banking network disappeared has long puzzled historians. In his captivating study, “Finding the Roman Empire’s Disappeared Deposit Bankers,” economist Morris Silver digs deep into the evidence—and the silence—to explain what really happened.

Drawing from legal texts, inscriptions, and economic reasoning, Silver argues that it wasn’t a natural decline, but imperial mismanagement and inflationary policies that dismantled the deposit banking system. His work sheds new light on a financial world that was far more developed—and far more vulnerable—than we might expect.

Banking in Bronze and Trust

Roman bankers didn’t just store money—they invested it. As early as 85 BCE, the crisis in Ephesus prompted authorities to grant local bankers a ten-year reprieve to repay their depositors, evidence of how deeply these institutions were embedded in financial life.

The argentarius often operated on what modern economists call a fractional reserve system. They accepted "non-sealed" deposits (deposita irregularia), lent out those funds at interest, and returned a portion of the profits to depositors.

A striking passage from The Digest of Justinian features Caecilius Candidus reassuring a client that:

“You do not have it lying idle.

I shall make it my business that you get interest on it.”

This wasn’t merely a courtesy—it was a compact of confidence, the very essence of deposit banking.

Unlike the image of Roman finance as a playground of senatorial elites, deposit banking was accessible to the middle classes. These banks served soldiers saving part of their pay, urban collegia managing funerary and charitable funds, and merchants navigating trade. Soldiers were even required to save, and in cities like Bonna, early bankers appear directly adjacent to legionary camps.

According to Silver:

“the presence of a banking system may reasonably be viewed as a benchmark in determining the sophistication of financial markets.”

These banks made capital mobile and allowed non-elites to participate in commerce without needing aristocratic intermediaries. And their reach was far from trivial: Scipio Aemilianus himself once kept over 1.2 million sesterces on deposit with a banker in 162 BCE.

From Confidence to Collapse

But this vibrant banking network began to unravel by the third century CE. The roots of the decline lay not in some natural economic evolution but in destructive imperial policy. Successive emperors devalued Rome’s currency through aggressive coin debasement and failed to adjust lending laws accordingly.

Inflation soared—by the time of Diocletian, it may have reached 23% annually—while a rigid interest rate cap of 12% remained legally enforced. This combination proved toxic. Banks could no longer offer depositors meaningful returns. They couldn’t charge borrowers enough to stay solvent. And they couldn’t refuse legal tender, even when its silver content had dwindled to near nothing.

Roman jurists, once supportive of market autonomy, increasingly sided with debtors.

“The state did not have to rely entirely on its own limited means to enforce maximum rates of interest,”

Silver writes—

“it could count on the active assistance of self-interested borrowers.”

The public began to hoard older, purer coins, exacerbating the liquidity crisis. What remained in circulation—like the degraded antoniniani—were coins so debased and poorly minted that:

“many lost their coating as the public grew expert in extracting the silvered veneer,”

Silver notes. Debasement became a visual cue of fiscal failure.

In the absence of profitable deposit banking, people reverted to lending in kind. Grain and goods replaced coins in many transactions, not because Rome was “primitive,” but because inflation demanded a hedge.

As Silver puts it:

"many in-kind transactions were hidden monetized transactions."

Meanwhile, previously strict professional boundaries collapsed—argentarii disappeared, and silversmiths took their name and some of their functions.

By the fourth century CE, there are virtually no attestations of deposit bankers in Italy outside major ports. The term argentarius vanished from the legal vocabulary of banking. Bankers were no longer mentioned in inscriptions. Public and private deposits likely dried up. What had once been an accessible network of financial intermediaries vanished into the fog of imperial overreach.

One revealing case, recorded by the Christian writer Hippolytus, tells of Callistus—future pope and former slave—who was entrusted with banking funds and failed disastrously, unable to return his depositors’ money. The episode reflects not just personal mismanagement but a broader fragility in late Roman banking.

State Sabotage, Not Market Failure

Why did the Roman banking system collapse? Silver's answer is blunt: government sabotage.

"The perverse decisions of Roman rulers during the third and fourth centuries had the ultimate effect of reducing the banking system to insignificance,"

he argues. Maximum interest rates, combined with unbridled inflation and the state's refusal to allow private actors to protect their capital, drove deposit banking to extinction. In a striking example of economic irony, Roman rulers sought to protect debtors so zealously that they wiped out the very institutions that allowed credit to flourish. In the end, both depositors and entrepreneurs lost, and so too did Rome’s broader economy.

This tale of vanished vaults is more than a footnote—it’s a warning. Roman deposit banking had matured into a sophisticated network, capable of channeling savings into trade and consumption. Its disappearance curtailed investment, strangled credit, and likely accelerated the broader economic stagnation of the late Empire.

As Silver concludes:

"The absence of a viable banking system had to negatively impact economic growth and living standards... How large these effects were can be debated, but not the fact that they existed."

(Finding the Roman Empire’s Disappeared Deposit Bankers, by Morris Silver)

Rome’s Invisible Banks: How Credit, Coin, and Collapse Shaped the Empire’s Financial Soul

Economist Peter Temin, in his pioneering paper “Financial Intermediation in the Early Roman Empire,” urges a radical reassessment.

"The issue turns out to be not whether financial markets in Rome resembled those in other advanced agricultural economies,"

he writes,

"but rather which 18th century European economy did it resemble most closely."

Banking, Roman Style

In modern terms, a bank is defined as a financial institution that accepts deposits and makes loans. This definition, Temin shows, was already in use among ancient historians like Bogaert and Andreau.

As aforementioned, Roman argentarii, along with coactores argentarii and nummularii, did precisely this. They took in deposits, managed accounts, and extended credit. These bankers were not mere money-changers. They operated in a legally recognized framework, kept records in ledgers called rationes, and participated in credit arrangements that served local commerce, international trade, and even public finance.

"Deposits are bank liabilities,"

Temin explains,

"They pay a lower rate of interest than other loans partly because the bank furnishes services in place of interest payments."

Deposits, Not Denarii

One of the strongest indicators of Rome's financial maturity is the existence of what modern economists call deposit banking. Temin, echoing the Digest, notes that Roman law distinguished between sealed deposits (meant for safekeeping) and unsealed deposits, which banks were allowed to use for lending—a practice strikingly similar to today’s fractional reserve system.

An example from the second century CE Egyptian papyri reads:

"Paid into the bank of Titus Flavius Eutychides... on condition that an equivalent amount should be paid at Alexandria to the official in charge."

This is, Temin points out, an interbank transfer. Roman banks could communicate, transfer funds, and honor each other's obligations. And there were real consequences when credit failed. As Josephus recounts, debtors in Antioch once set fire to the city center to destroy debt records. This desperation only makes sense in a world where written contracts carried enforceable financial weight.

Not Just the Elite

Unlike the elite moneylenders who extended personal loans to cities or clients, Rome’s deposit banks served ordinary people. Collegia (associations), municipal treasuries, and even soldiers used these services. One banker from Pompeii, Lucius Caecilius Jucundus, left behind tablets detailing receipts from auctions, credit extended, and tax allocations—suggesting that his business operated very much like a private financial institution.

Furthermore, temples and local governments acted as proto-financial intermediaries. Endowments held in temples were often loaned out at interest to fund rituals or maintenance. A remarkable inscription records a donor's instructions to a collegium to:

"loan out the funds and use the returns to fund their feasts and other activities."

Temin summarizes:

"Temples were an important means of ‘pooling’ investment funds in the early Roman Empire."

Rome and the Economic Modernity Debate

The traditional view of Rome's economy, shaped by scholars like M.I. Finley, characterized it as a "primitive" agrarian society. Temin challenges this directly:

"Financial institutions in the early Roman Empire were better than those of 18th century France and not too far from those of 18th century England and Holland."

He illustrates this with a hierarchy of financial sophistication:

- From internal savings to informal credit,

- to true financial intermediation,

- and finally to capital markets.

Rome, he argues, reached the third level. While it lacked public stock exchanges, it possessed the banking layer that allowed savers and borrowers to connect indirectly through trusted institutions. This structure enabled considerable investment and economic flexibility.

Columella advised calculating vineyard yields based on interest from borrowed capital. Livy and Cicero recorded real-time shifts in market interest rates. Even the Emperor Trajan, when confronted with idle public funds in Bithynia, advised Pliny to lower the interest rate to stimulate lending—an action Temin calls evidence that "Romans conceptualized a demand curve for loans."

“The public money, my Lord, which exists in the city of the Prusenses, has long remained unused. In order to bring it into some sort of productive use, I issued an edict inviting anyone who wanted to borrow to declare so. However, no creditors came forward, even though it was permissible to stipulate for interest well below 12 percent. Still, I thought it worthwhile to try, so that the custom, long fallen into disuse, might slowly grow back.”

Pliny the Younger, Epistulae 10.54 (Pliny to Trajan)

"You have done well, my dear Secundus, in attempting to bring back into use the public money that has long lain idle. What remains is for you to persist, and for those who can borrow to prove trustworthy. It is in the public interest that money be put to good use. If no one is found willing to borrow, the interest may be reduced, provided that private relief does not harm the public good.”

Trajan’s response (10.55)

A System That Vanished

Despite its reach and robustness, Rome’s deposit banking system disappeared by the third century CE. As Morris Silver has argued, it was likely destroyed not by market failure but by destructive imperial policies: rampant coin debasement, interest rate caps, and legal favoritism toward debtors.

But during its prime, the Roman financial system channeled capital through banks, temples, and public treasuries with remarkable nuance. It facilitated trade across seas, enabled urban development, and extended financial tools to ordinary citizens.

Rome did not lack banks. It simply buried them—beneath marble, memory, and legal complexity. Rediscovering them invites us to redefine what modern finance, truly means.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: