A Sail Above the Sand: Did the Colosseum Really Have a Retractable Roof?

Imagine 50,000 Romans seated in the blazing summer sun, cheering gladiators while the midday heat bears down on the mighty Colosseum. Yet, their faces are shaded, cooled by a system so advanced that even modern engineers marvel at its ingenuity. How did the Romans achieve this?

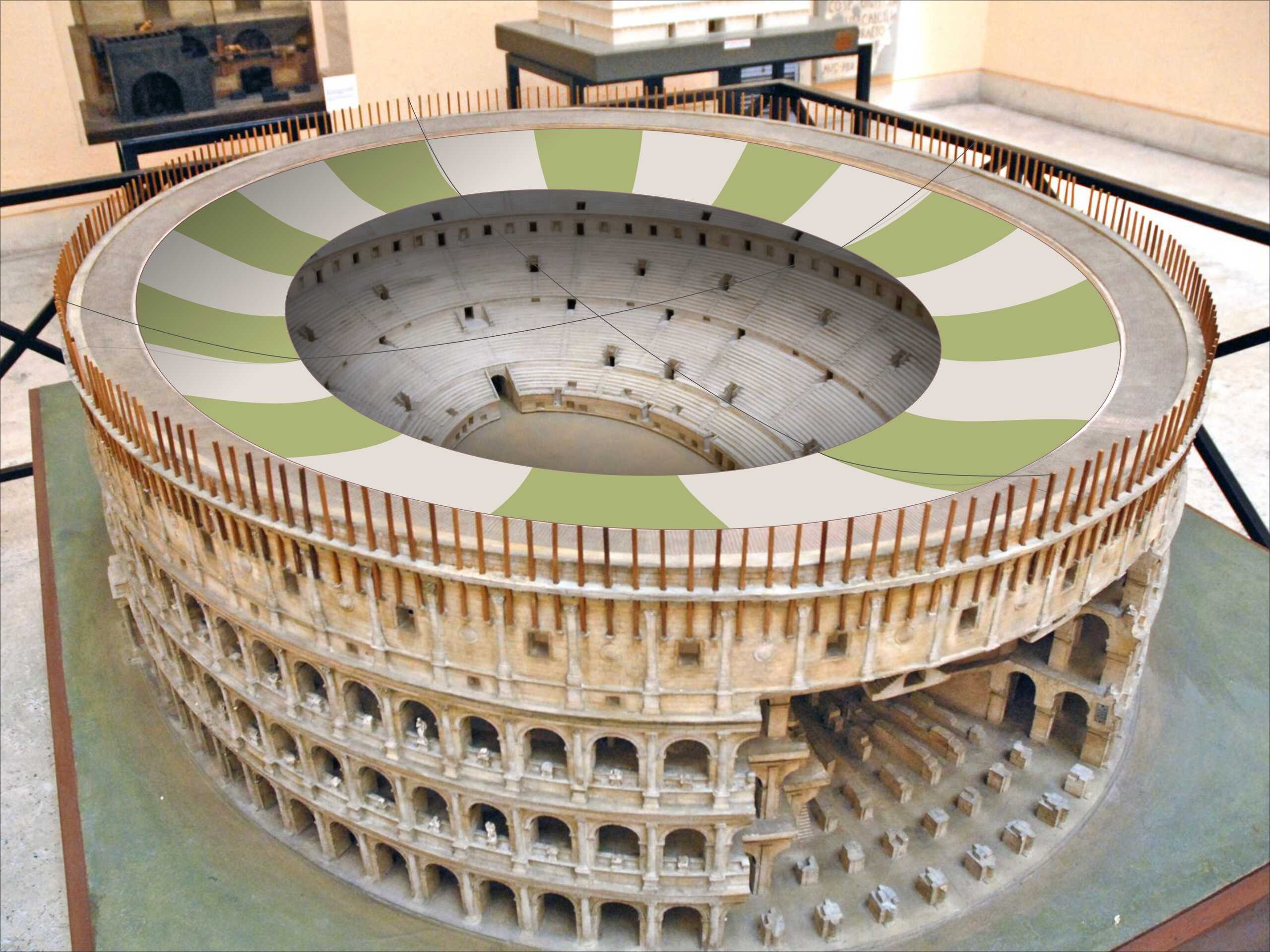

If you visited the Colosseum today, it might seem hard to believe that this ancient stone giant once pride itself on a colossal awning system, known as the velarium, shielding spectators from the brutal Roman sun. How could linen sails, ropes, and masts cover an arena the size of a modern football field?

How did it work, and who orchestrated this feat of engineering? The answers lie not just in the ingenuity of Roman technology but maybe also in the hands of hundreds of naval sailors brought in to operate it – a connection between sea and sand few would expect.

The Colosseum: A Marvel of Architecture, Politics, and Propaganda

The Flavian Amphitheater, known today as the Colosseum, was the largest and most impressive amphitheater in the Roman Empire. Built under the Flavian dynasty, its grand scale and sophisticated features were remarkably ahead of their time, resembling modern sports stadiums in many ways.

It stood about 48.5 meters tall (159 feet), equivalent to a modern 15-story building, and covered an immense area of nearly 24,000 square meters (six acres). With 80 entrances, including four special entrances on the main axes, the structure was designed for efficiency. Spectators could access their designated seating areas through an organized system of staircases and barriers.

Modern estimates suggest the Colosseum could accommodate between 50,000 and 55,000 people, though ancient sources like the Chronograph of 354 CE claim it could hold as many as 87,000. Amenities included snacks, water fountains, and even flushing toilets—facilities that mirror those in today’s stadiums.

The Colosseum was much more than a venue for gladiatorial games and public spectacles. Its construction, initiated by Vespasian nearly a decade before its inauguration, was ideologically charged. Vespasian deliberately chose the site of Nero’s Domus Aurea, a vast palace complex that had included an artificial lake. Nero had built this palace following the Great Fire of 64 CE, seizing large portions of Rome for his personal use.

By dismantling Nero’s opulent palace and replacing it with a public entertainment venue, Vespasian presented the Flavian dynasty as the champions of the people, restoring Rome to its citizens and distancing the new regime from Nero’s reputation for tyranny and extravagance. (A monument to Dynasty and Death. The story of Rome's Colosseum and The Emperors who Built it, by Nathan T. Elkins)

The Enigmatic Awning Systems of Theatres and Amphitheatres

So, was the Colosseum shaded? Yes, like all the Roman theaters and amphitheaters. The Roman awning system, commonly referred to as the vela (Latin for “sails”), was a remarkable innovation that provided shade to spectators in Roman theatres and amphitheaters during the Empire.

However, its precise operation and origins continue to puzzle historians. While references to the vela exist in historical texts, only limited evidence—pictorial, physical, literary, and epigraphic—remains, leading to conflicting interpretations.

Although modern historians often use velum (singular), the correct ancient term is vela, the plural form. Occasionally, other terms like velaria (Juvenal), carbasus (Lucretius, referring to linen), and parapetasmata (Cassius Dio, meaning curtains) appear. This diversity of terminology highlights the broad use and understanding of the system in antiquity.

The earliest references to the use of awnings trace back to Quintus Catulus, a public official around 78 BCE. Pliny the Elder writes:

"In more recent times linens alone have been employed for the purpose of affording shade in our theatres; Q. Catulus having been the first who applied them to this use, on the occasion of the dedication by him of the Capitol."

Similarly, Ammianus Marcellinus echoes this:

“The awnings of the theatres, which Catulus, in his aedileship, imitating Campanian wantonness, was the first to spread.”

Both statements suggest that the Romans adopted the shading system from Campania, likely influenced by the comfort-seeking practices of the Pompeiians.

Evidence of Awnings in Pompeii and Rome

The vela likely predated permanent stone theatres in Rome. Lucretius, writing in the 1st century BCE, mentions theatrical awnings in temporary wooden theatres built for games long before Pompey’s Theatre (55 BCE), Rome’s first stone theatre.

Literary works from Propertius and Ovid further confirm the presence of awnings in theatres during this period. Propertius laments, “No rippling awnings hung o'er the hollow theatre,” indicating the absence of awnings in earlier times compared to their ubiquity in his day.

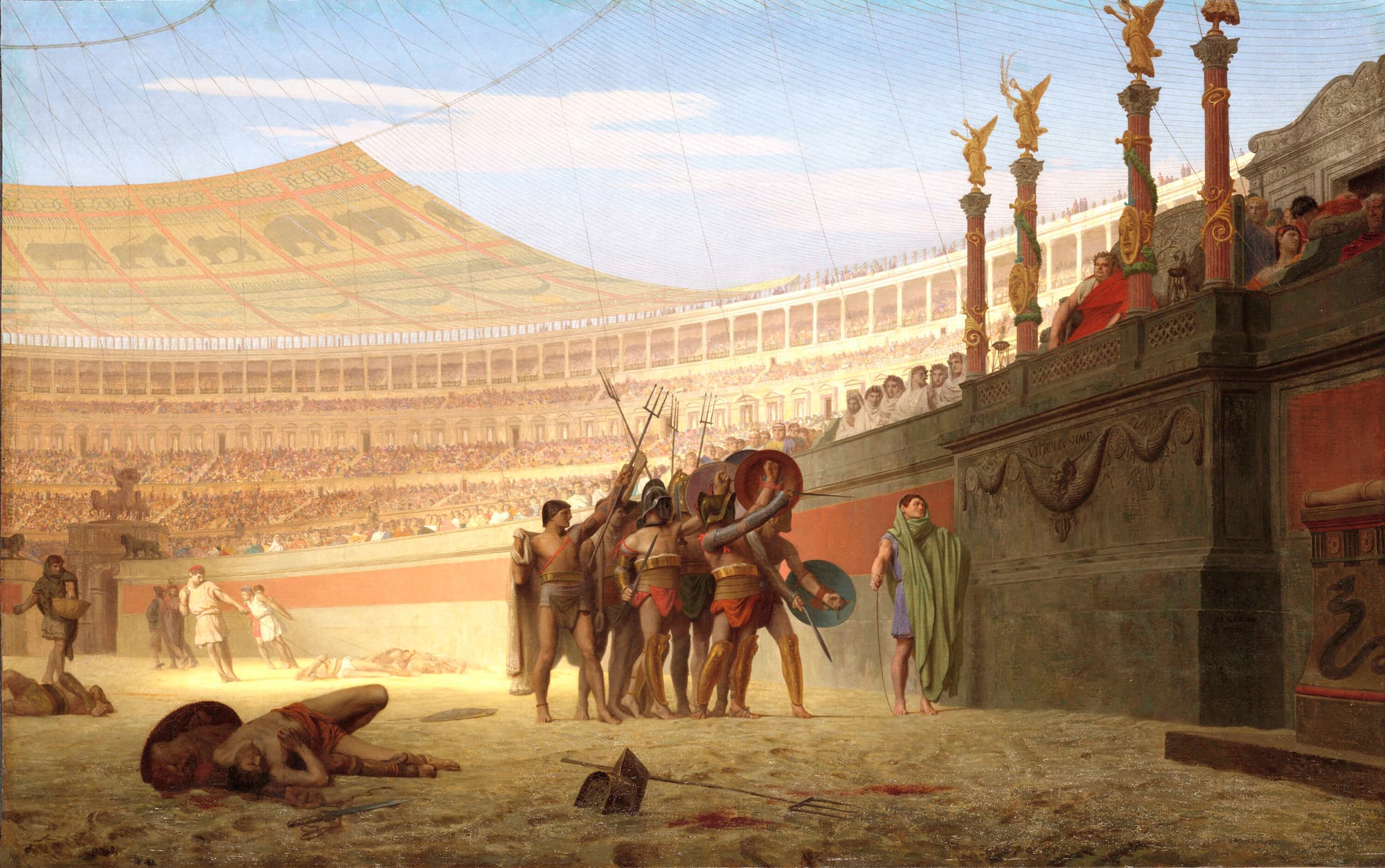

Pompeii, in particular, played a significant role in the history of the vela. Provisions for awnings are evident in the architectural remains of the Large Theatre and the Amphitheatre, the latter built in 80 BCE. A mural dated to 59 CE vividly depicts awnings stretched over Pompeii’s amphitheater, offering pictorial proof of their existence.

Inscriptions further confirm the use of awnings in gladiatorial games at Pompeii. One such inscription reads: “There will be a hunt and the awning will be spread,” dating from the reign of Nero between 50 and 54 CE. While the Large Theatre at Pompeii dates to the 2nd century BCE, it is believed that the Romans installed provisions for awnings during its reconstruction around 3-2 BCE.

Theories on the Origin of the Vela

Though the awnings were credited to Pompeii, their origin may lie further back with the Etruscans. Etruscan influences on Roman culture are well-documented, including their introduction of wooden grandstands for scenic performances as early as 364 BCE. A 5th-century BCE wall painting from the Tomb of the Two-Horsed Chariots in Tarquinia depicts a cloth covering draped over crossbeams, shading spectators seated on wooden benches.

This setup closely resembles later Roman awning systems and could have served as a prototype for the vela. Since the Etruscans had settlements in Campania, the practice of shading spectators may have passed to Pompeiians and subsequently credited to them.

The Roman Awnings: Luxury or Necessity?

The Romans may have borrowed the design of shaded grandstands from the Etruscans, but the adoption of awnings—vela—was significantly delayed. This delay likely stemmed from Etruria’s early decline and Rome’s period of austerity leading up to the first century B.C., when awnings began to appear.

Roman writers such as Valerius Maximus and Ammianus Marcellinus described the vela as a “luxury” and even as an indulgent act of “wantonness,” emphasizing that the Romans initially viewed the innovation as excessive rather than essential.

The primary function of the vela was to shield people from the sun’s intense heat, which was a notable issue in Roman theatres and amphitheaters.

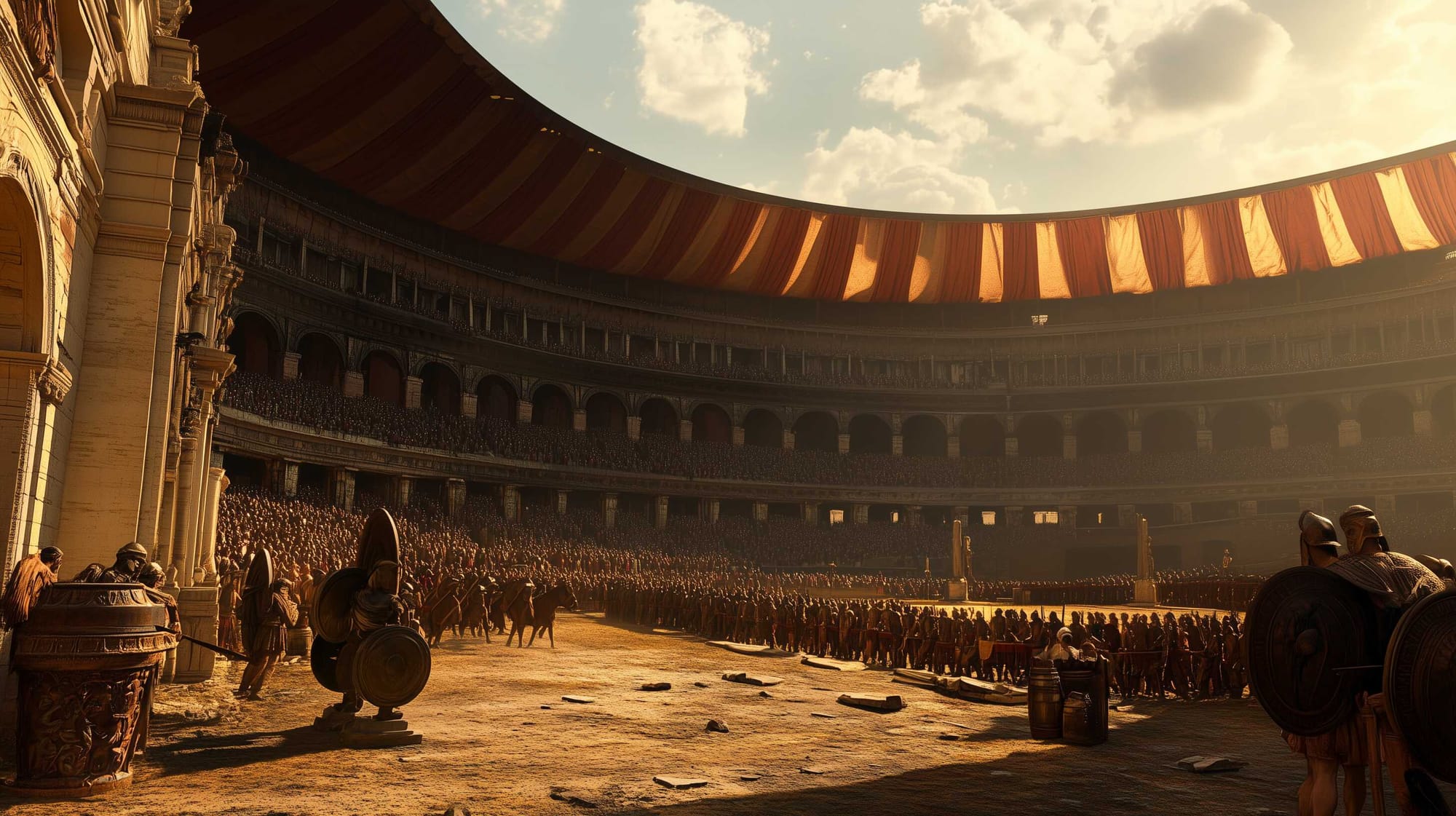

A possible representation of the shade offered by the vela (awning) of a Roman arena during gladiatorial games. Illustration: Midjourney

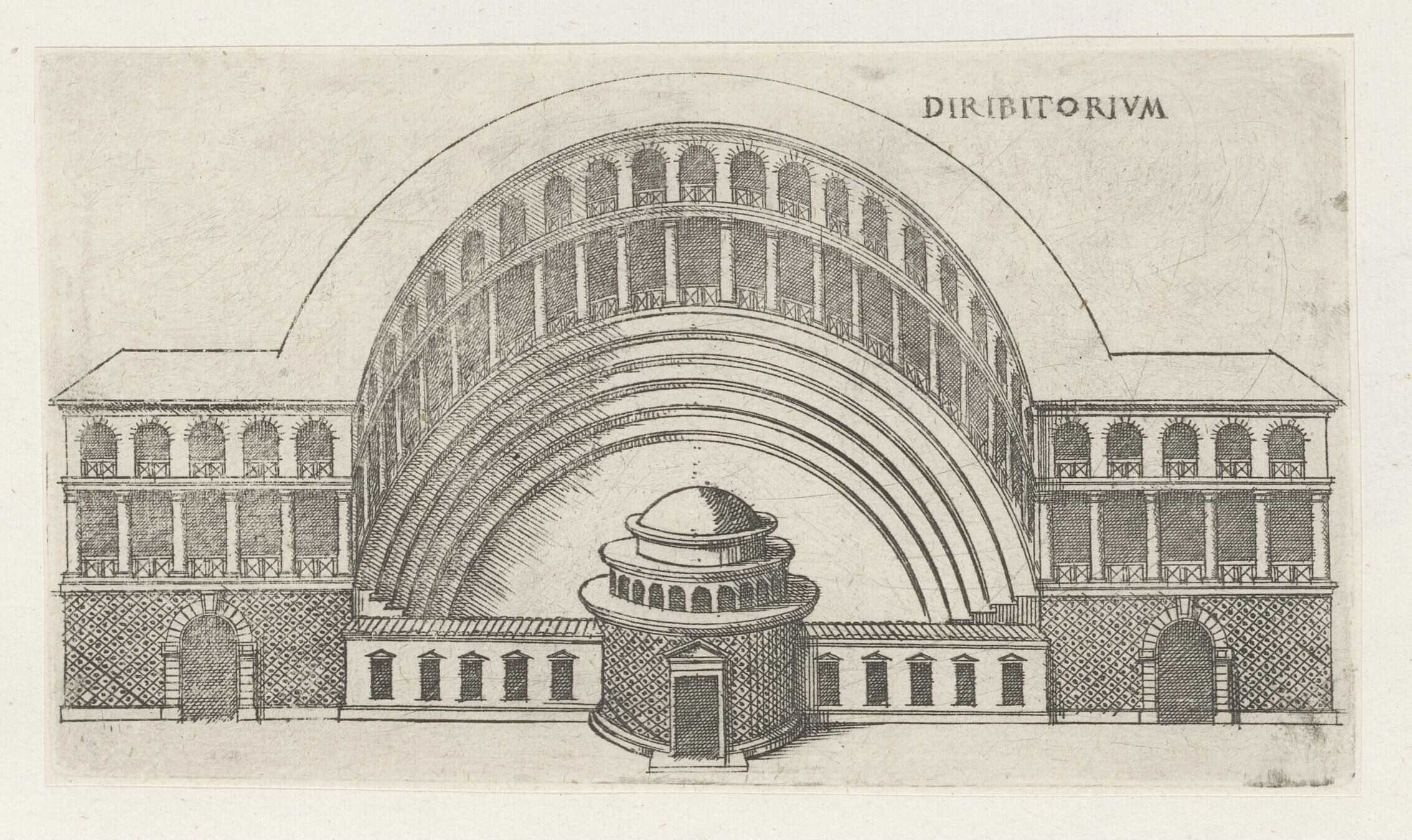

Cassius Dio highlighted the discomfort caused by the sun during Caligula’s reign, noting that senators were permitted to wear hats in the theatre to protect themselves. On particularly sweltering days, they even abandoned outdoor performances, relocating indoors to the Diribitorium, a hall furnished with seating.

Health concerns also played a role in the adoption of awnings. Vitruvius, the Roman architect, issued a stark warning against constructing theatres where the auditorium faced the sun. He explained:

“For when the sun fills up the cavity of the theatre, the air confined in that compass, being incapable of circulation by its stoppage therein, is heated and burns up, extracts, and diminishes the moisture of the body.”

This passage underscores the Roman belief that prolonged exposure to the sun was not just uncomfortable but potentially harmful to their well-being.

While the vela may have started as a luxury, its practical purpose in protecting audiences from the scorching heat of Roman summers ultimately solidified its place as a functional feature of theatres and amphitheaters. These awnings were not employed during periods of inclement weather, as evidenced by three passages from the Roman poet Martial:

“[Your broad-brimmed hat] will be a spectator with you in Pompey's Theatre, for blasts of wind are apt to deny the people an awning.”

“Accept a sunshade to subdue the overpowering heat; even though there will be a wind, your own awning will cover you.”

“However slippery is the stage with a corycian saffronshower, and although rushing winds tear at the awning that cannot be spread....”

The Romans seem to have quickly realized that strong winds could easily destroy the vela. Lucretius, when describing the awnings in temporary theatres, vividly remarks on the noise and destruction caused by the wind, likening the resulting sounds to thunder:

"The noise [the clouds] make above the levels of the outspread world is comparable to the intermittent clap of the awning stretched over a large theatre, when it flaps between poles and crossbeams, or to the loud crackling, reminiscent of rending paper, that it makes when riotous winds have ripped it."

Ammianus Marcellinus makes a remark that implies the awnings remained in place even when the theatre was not actively in use:

"But of the multitude of lowest condition and greatest poverty... some lurk in the shade of the awnings which Catulus in his aedileship, imitating Campanian wantonness, was the first to spread."

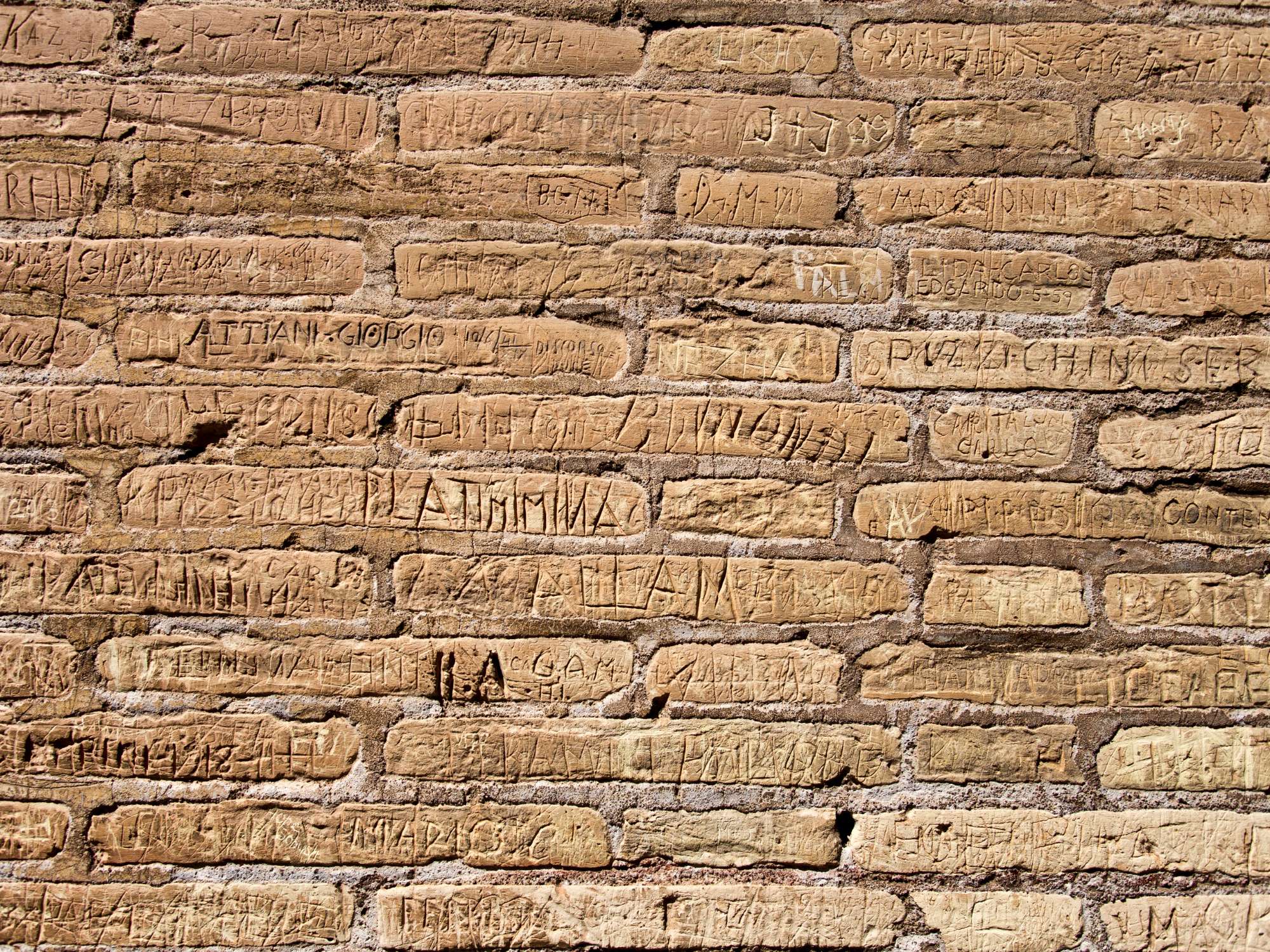

Once the awnings were deployed for the ludi (games), they seem to have remained in place until the festivities concluded, which could last for several days. It is often suggested that sailors operated the awnings, standing in the upper gallery of theatres and amphitheaters. This belief appears to stem solely from a passage in the Scriptores Historiae Augustae, specifically in the section concerning Emperor Commodus:

“He became convinced that he was being laughed at, and gave orders that the Roman people should be slain in the Amphitheatre by the marines who drew the awnings [militibits classiaris qui vela ducebant]”

It is certainly reasonable to suggest that the marines of the Misenum Navy, stationed in Rome and skilled in handling ropes and pulleys, were a logical choice to operate the awnings in the Colosseum. These marines were often employed for staging naumachiae (mock sea battles) in Rome.

However, this does not necessarily mean they were used on every occasion when awnings were deployed, nor does it imply that every Roman town with an amphitheater covered by awnings had a contingent of marines nearby to manage the vela. Before concluding that marines were universally responsible for operating awnings, it is important to consider several points:

- The claim originates from the Scriptores Historiae Augustae, a source from the fourth century A.D. known for its inaccuracies;

- Only the Colosseum is specifically mentioned;

- The statement refers to an event in the late second century A.D. that may not have actually occurred.

Another possibility is that gladiators may have had some involvement with the awnings in amphitheatres. Friedländer (Ludwig Heinrich Friedländerwas a German historian noted for his comprehensive survey of Roman social and cultural history), suggests that "the velarii who drew up and managed the awnings of the amphitheater may have been part of the gladiatorial families."

This assertion likely stems from a confusing passage in Juvenal, where the word velaria is uniquely used to refer to awnings: "In like fashion he would commend the thrusts of a Cicilian gladiator or the machine which whisks up the boys into the awning."

Theories and Evidence Behind the Awnings

The Roman awnings, present a fascinating yet unresolved puzzle for historians. These massive cloth coverings, likely imported to Rome from Pompeii in the late 1st century B.C., served primarily to shield spectators from the sun, as already mentioned.

The adoption of the awning as a luxury feature was gradual, as the Roman Republic was marked by austerity until the 1st century B.C., and even then, authors such as Valerius Maximus and Ammianus Marcellinus described it as an indulgence.

The vela were dyed or painted bright colors, adding a striking visual element to the experience. Lucretius vividly describes their effect:

“Awnings, yellow and red and purple, when stretched over great theatres, they flap and flutter, spread everywhere on masts and beams. For there they tinge the assembly in the tiers beneath, and all the bravery of the stage, and constrain them to flutter in their colors.”

Pliny the Elder mentions further advancements under Nero, writing that awnings of sky-blue cloth, spangled with golden stars, were used, likely to impress foreign dignitaries such as Tiridates of Armenia during his visit in A.D. 66.

“Awnings have been lately extended, too, by the aid of ropes, over the amphitheatres of the Emperor Nero, dyed azure, like the heavens, and bespangled all over with stars.

Those which are employed by us to cover the inner court of our houses are generally red: one reason for employing them is to protect the moss that grows there from the rays of the sun.

In other respects, white fabrics of linen have always held the ascendancy in public estimation.”

Cassius Dio adds that the center of Nero’s awnings featured an embroidered image of the emperor driving a chariot, surrounded by stars. Such extravagant designs, however, were the exception rather than the norm.

When not in use, the vela were likely rolled up or gathered onto the masts around the edges of the seating area, much like sails on a ship. Martial alludes to this function in an epigram comparing Lydia’s physique to “an awning that does not belly to the wind in Pompey’s Theatre.” This suggests that the folded or gathered awnings remained visible when they were not unfurled.

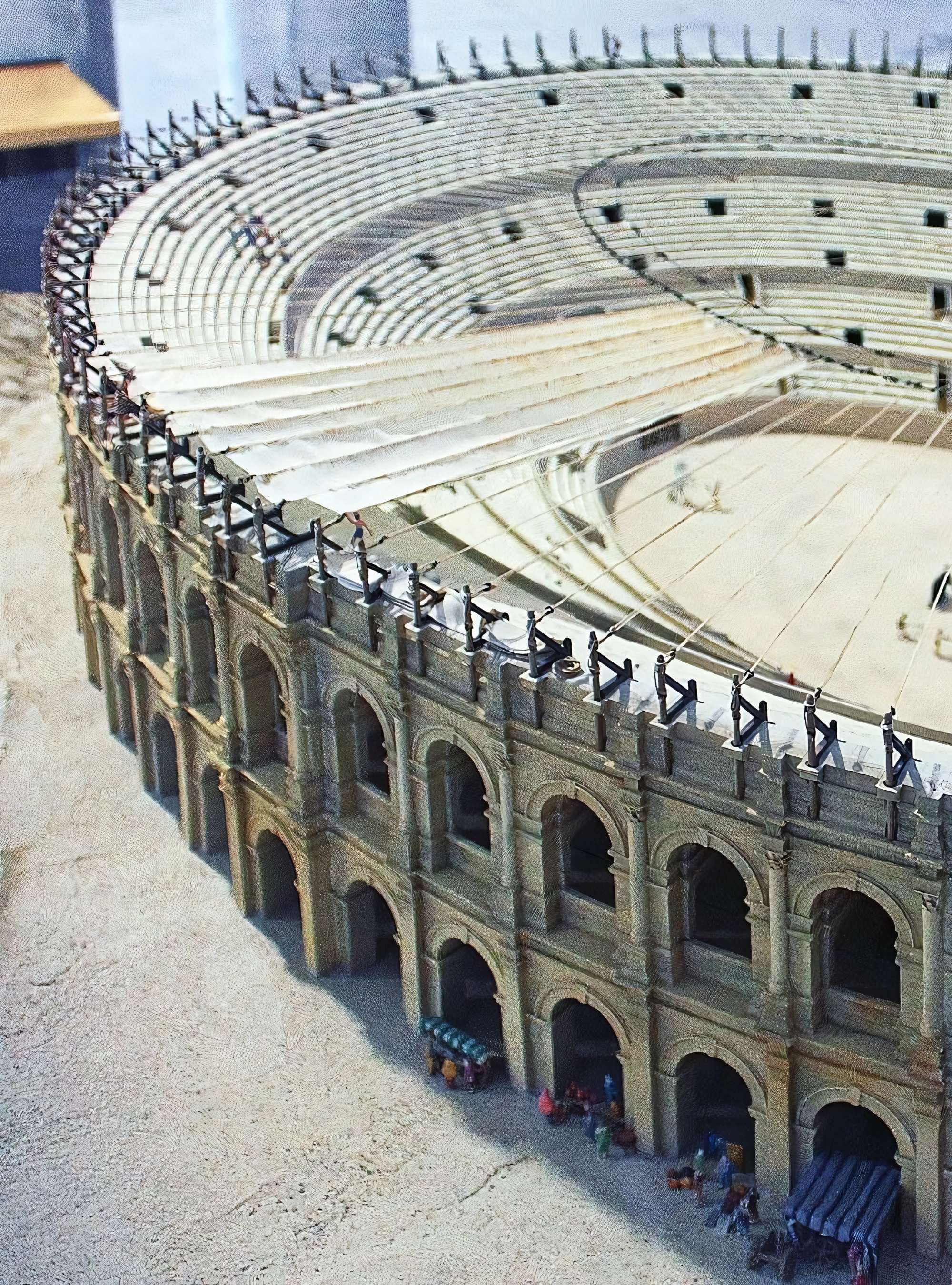

Physically, the remains of Roman theatres and amphitheaters provide some clues about the awning systems. Corbels and cornices with apertures were installed along the tops of outer walls, likely to hold wooden masts supporting the vela. The masts would pass through an upper row of apertures, often accompanied by sockets or openings in a lower row to stabilize the poles.

This architectural feature, found at sites such as Nîmes, Arles, Pola, Pompeii, and the Colosseum, was consistent across different theatres and amphitheaters. However, variations existed. For instance, in Pompeii’s Large Theatre, the corbels were located on the inner wall of the seating area rather than the outer wall.

The mural from Pompeii previously shown offers one of the clearest visual representations of the vela in use. It shows the awning stretched across the amphitheater, with its ends anchored to nearby towers, covering only part of the structure. This depiction suggests that not all spectators were shaded by the awning and that the vela may not have been a single expanse but a system of smaller awnings. Latin writers frequently refer to the vela in the plural, reinforcing the idea of multiple sections rather than a single cloth.

Scholars have proposed several reconstructions for how the awnings functioned. Josef Durm’s (architect, author, architectural historian and master builder) version for the Colosseum imagines a massive cloth stretched over double rows of masts, but this solution raises concerns about the structural feasibility—particularly the outward pull that would stress the Colosseum’s walls.

J.H. Parker (an English archaeologist, writer on architecture, and publisher) proposed a more plausible system, suggesting that masts positioned both along the outer rim and within the arena supported the vela at multiple points to reduce sagging. However, no evidence of such inner masts has been found outside the Colosseum.

Some theories have also explored the possibility of vertical awnings that could be raised and lowered like curtains. Josef Dunn briefly suggested this design, but it fails to align with literary references describing the awnings as “stretched” and “hung over” the seating areas.

While the precise mechanics of the vela remain uncertain, the evidence suggests a combination of masts, ropes, and beams was used to stretch and stabilize the awnings. Over time, advancements like the use of ropes in Nero’s era may have replaced earlier systems involving crossbeams. The visual impact of the brightly colored or decorated awnings must have been remarkable, even if they only covered part of the audience or were reserved for special events. (The awnings of Roman Theatres and Amphithetres, by Robert B. Montilla, Teaching Assistant at Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: