The Senate of Rome, Senatus Populusque Romanus: Backbone of a Republic, Shadow of an Empire

From royal council to imperial echo, the Roman Senate survived upheaval, adapting to centuries of change. Even stripped of power, it remained the beating heart of Roman identity—a symbol more potent than its voice.

It began as a council of elders — a gathering of wise men advising Rome's earliest kings. Yet over the centuries, the Senate of Rome evolved into the Republic’s anchor and, later, the Empire’s echo.

From fierce debates under the open sky of the Comitium to the hushed formality of imperial senatorial decrees, the Senate was both a stage for politics and a symbol of Roman identity. Revered, feared, manipulated, and at times ignored, it endured across regimes, wielding power or serving as ornament — always present, rarely powerless for long.

How Rome Built Its Senate?

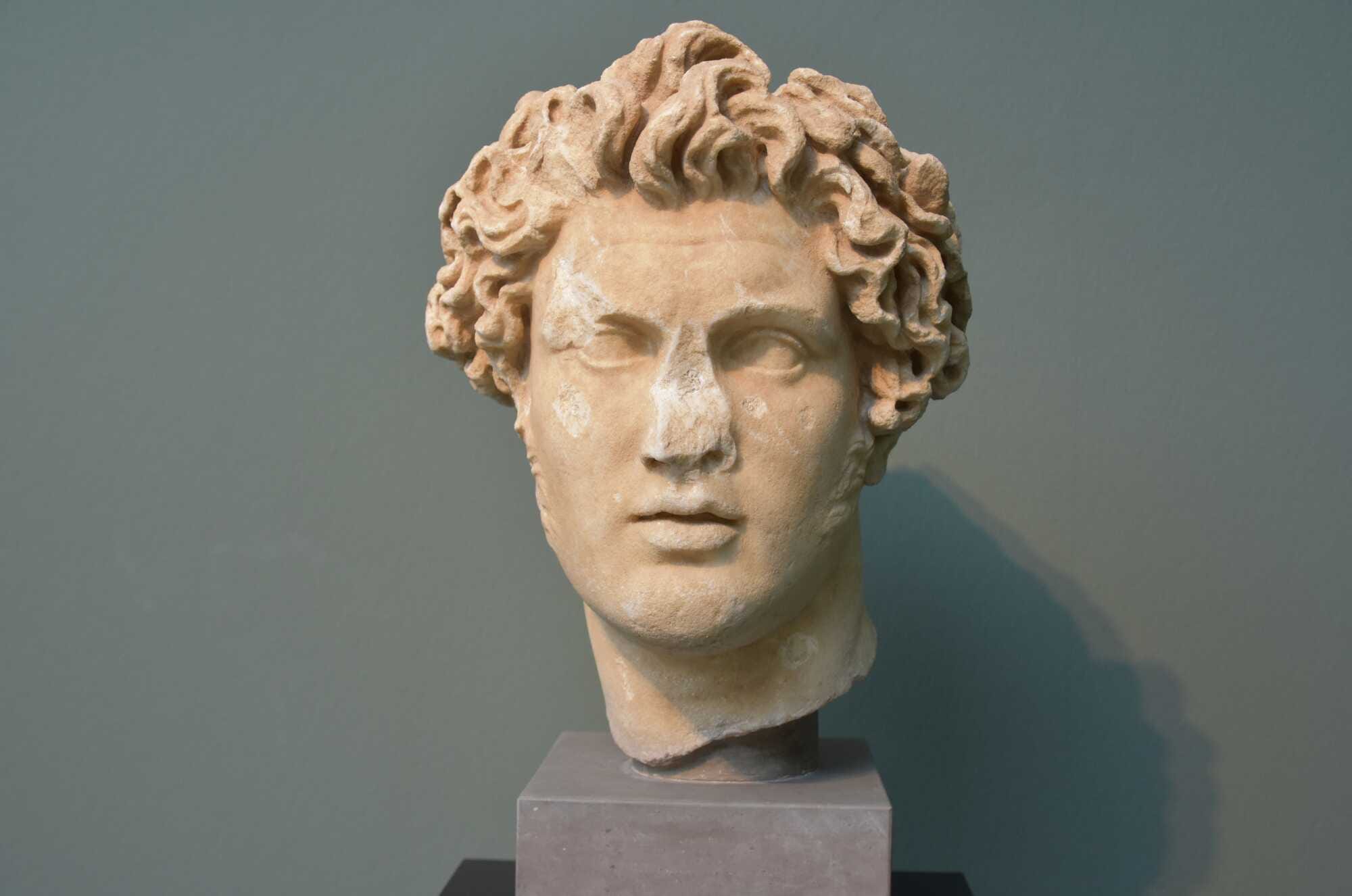

The Roman Senate traces its legendary origins to the founding of Rome in 753 BCE, traditionally established by Romulus with 100 noble members. This number was later said to have increased to 300 under the Tarquins, forming the foundation of a political body that, while evolving in role and power, endured in various forms for over a millennium.

Initially, during the monarchy, the Senate served as an advisory council to the king, composed of elder statesmen (senes) whose wisdom guided decision-making in a preliterate society. During the Republic, senators were drawn from Rome’s elite families, typically after holding a magistracy. While the exact size of the Senate in the early Republic is unclear, by the Middle Republic it was around 300 members.

The designation patres et conscripti reflects the early division between patrician founders and later appointees, including plebeians. The Senate played a dominant role in directing state policy, even though formal sovereignty lay with the Roman people. It issued senatus consulta—advisory decrees—upon being convened by a magistrate. These decrees, while not technically laws, often guided magistrates' actions or influenced legislative proposals brought before the people.

A Council of Kings: The Roman Senate Between Prestige and Power

When Cineas, the ambassador of King Pyrrhus, returned from Rome in 279 BCE after an unsuccessful diplomatic mission, he famously remarked that:

“the Senate appeared to him to be a council of many kings”

Plutarch, Pyrrhus 19.5

This comment, widely repeated in ancient literature, captured both the senators’ collective dignity and their political authority. It also underscored the paradox of describing a republican body with monarchical language, revealing how Roman political identity blurred traditional Greco-Roman categories of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy.

Polybius, writing in the second century BCE, interpreted the Roman Republic as a mixed constitution, combining the three classical forms of government — a concept he adapted from Aristotle. He viewed the Senate as the stabilizing aristocratic element, central to Rome’s political resilience and imperial success. Cicero later echoed this view, praising the Senate as the Republic’s guardian:

“They wished that the magistrates should avail themselves of the authority of this order, and that they should be almost the servants of this most august council”

Despite the lack of a formal constitution, institutional functions were documented through procedural laws and surviving accounts of political practice. Key legal texts, such as the lex Publilia of 339 and the lex Cornelia of 67, outlined the Senate’s role in the legislative process.

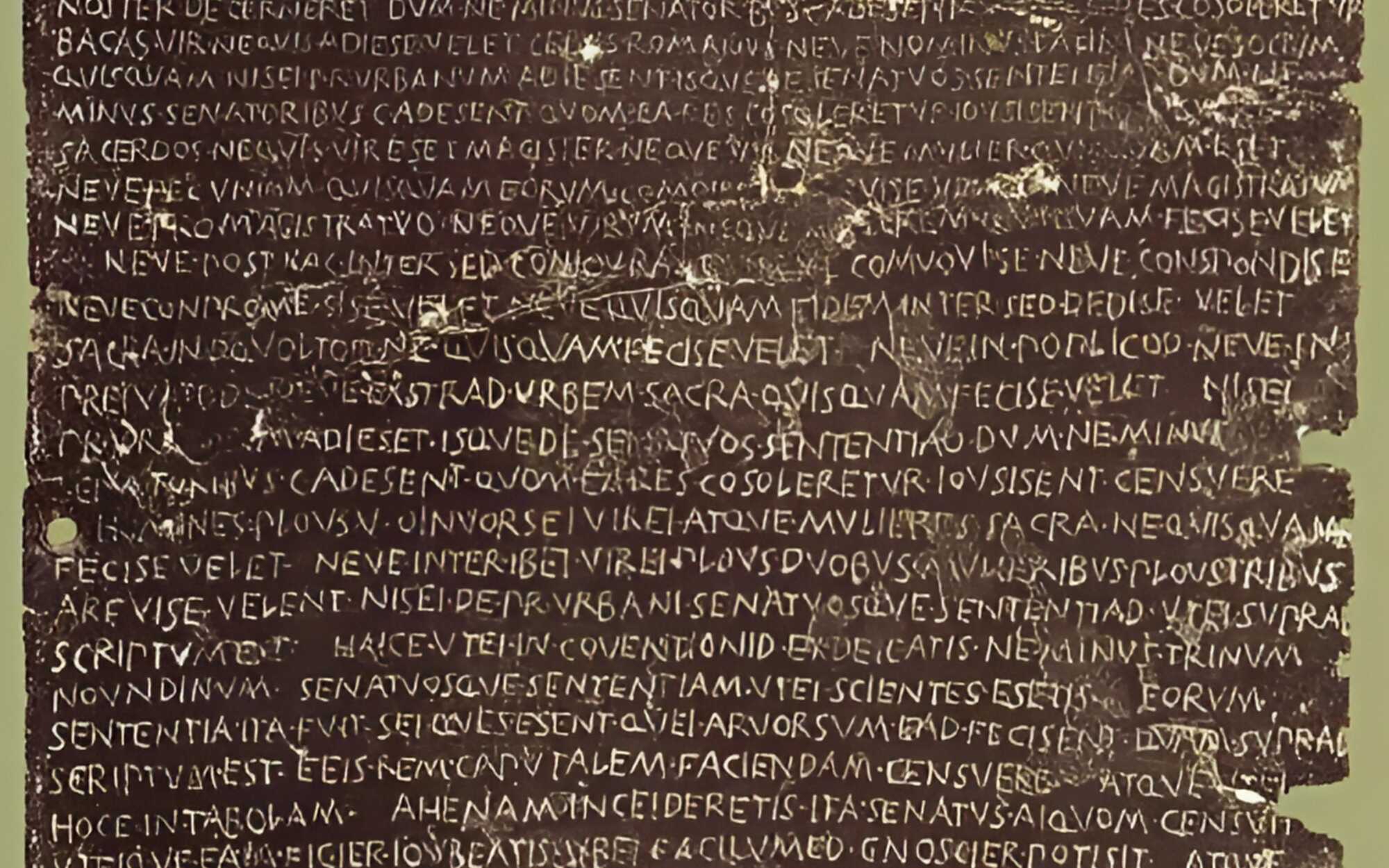

Much of what is known, however, comes from narratives like Livy’s detailed year-by-year accounts between 218 and 167 BCE, inscriptions like the senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus, and diplomatic decrees engraved in stone by Greek cities recognizing Senate decisions.

The later Republican period, particularly from 70 BCE onward, is enriched by sources such as Cicero’s speeches and letters, procedural treatises like Varro’s for Pompey, and historical works by Sallust, Cassius Dio, and others. These reveal the Senate’s operational character—its procedures, internal debates, and influence—complementing earlier 19th-century institutional studies by scholars like Mommsen and Willems.

However, the Senate’s real significance lay not only in its formal functions but in its daily political activity, its ability to issue binding senatus consulta, and the cultural authority it wielded despite its advisory role. This realization prompted newer scholarly approaches from the 1980s onward, focusing on foreign policy, deliberative dynamics, and the political interplay between magistrates and the Senate.

Conversely, Fergus Millar’s (a British ancient historian and academic) influential work shifted the focus toward popular assemblies and the Republic’s democratic dimensions, temporarily sidelining interest in the Senate’s inner workings. Still, the Senate remains key to understanding how Rome’s political elite—its nobilitas—exercised influence not only through elections and patronage but also through the rhythms of deliberation and decision-making within the Curia.

Debate and Authority: How the Roman Senate Reached its Decisions

Despite the formal structure of its meetings, the Roman Senate functioned as a space where animated and even spontaneous debate was not only permitted but expected. Every session was led by a magistrate who structured the discussion: convening the body, setting the topic, polling members in order, proposing motions, and overseeing the vote.

While this might suggest top-down control, in practice, the magistrate generally refrained from influencing individual opinions — a norm respected even during politically charged periods like the late Republic. Nevertheless, influence could be exerted subtly.

Prominent figures such as Pompey and Crassus employed proxies to put forward their favored motions. The power to appoint the primus rogatus gave magistrates additional leverage, as illustrated by Caesar in 59 BCE when he replaced Crassus with Pompey following a political marriage alliance.

Yet senators guarded their independence: being asked to speak first was an honor, but one with the expectation of individual judgment. The ius sententiae, or right to express an opinion, allowed senators—particularly those of higher rank—to speak freely, sometimes before being formally invited, or to amend their positions as the debate progressed.

Historical examples abound: in 204 BCE, senators demanded to be heard on punishing Latin colonies, and in 63 BCE, during the debate on Catiline’s conspirators, some like Silanus even reversed their stance after hearing others' arguments. Senators could submit pre-written proposals, as Cicero once did, and demanded procedural checks such as quorum verification.

The final text of a senatus consultum reflected the prevailing motion, often introduced with the phrase “the decree of the Senate was passed according to the proposal of x”. One of the most vivid examples of senatorial deliberation remains the session of December 63 BCE, where differing opinions clashed in real time:

- Silanus ( a roman senator) initially proposed execution, Caesar advocated imprisonment, and Cato, speaking last, swung the mood back to Silanus’ view amid outbursts of applause and protest.

- Cicero, despite being the presiding magistrate, also voiced his disapproval of Caesar’s stance — a move highlighting the fluidity of roles within such debates.

Toward the end of the Republic, even the tribunician veto, which could block decrees, was strategically bypassed. In 51 BCE, the Senate began drafting senatus consulta despite expected opposition — a tactic aimed at preserving institutional momentum and asserting the Senate’s supremacy. The label given to these preemptively prepared texts, senatus auctoritas, underscored the enduring moral authority of the body, which was not so easily undone by procedural roadblocks.

Center of Power or Stage of Struggle? The Senate’s Place in the Roman Republic

Defining the Senate’s institutional role in the Roman Republic is complex. While Roman political theory emphasized the Senate’s auctoritas, this authority manifested chiefly through relationships—with magistrates, popular assemblies, and foreign envoys.

Polybius saw Rome’s political system as a mixed constitution whose balance depended on mutual constraints between aristocracy (the Senate), monarchy (magistrates), and democracy (assemblies). While modern historians still use this model, they increasingly examine the practical cooperation among institutions over confrontations.

The Senate’s daily operations unfolded at the heart of Rome’s civic space, in close proximity to tribunes and assemblies. Though its meetings were formally closed to the public, the public was frequently informed via contiones (the contio was an ad hoc public assembly in Ancient Rome, which existed during the monarchy as well as in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire) and later, through the publication of acta senatus—a reform initiated by Caesar.

The Senate’s influence was most visible in foreign policy, where it worked in tandem with magistrates to receive envoys, assign military commands, authorize peace treaties, and manage provincial territories.

A possible representation of a Roman Senator listening to a fellow colleague while he is speaking to the Senate. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

In domestic politics, the Senate verified candidates for office and advised on laws, even after its legal involvement was no longer required. Tribunes sometimes withdrew rogationes (in the Roman Republic, a rogatio is a proposed piece of legislation — all legislation during the Republic was moved before an assembly of the people), in the face of senatorial opposition or amended them under pressure.

In other cases, senators countered tribunes with alternative proposals. However, tensions could escalate: Caesar, when faced with Senate resistance, bypassed the chamber altogether and took his laws directly to the people, marking a shift that Cassius Dio viewed as undermining traditional constitutional norms.

Throughout the Republic, the Senate’s influence waxed and waned, subject to broader political currents. While some scholars view its authority as gradually eroded by populist challenges and strong generals, others highlight its enduring centrality to Roman governance well into the late Republic.

From Ascendancy to Adaptation: The Senate's Journey Through the Middle and Late Republic

The Senate’s undisputed dominance during the so-called ‘middle Republic’—roughly from the early third century BCE to the Gracchi—traced its origins to a critical reform, the lex Ovinia, which transferred the authority of appointing senators from consuls to censors. This shift solidified the Senate as a stable, autonomous institution with enduring authority.

Livy’s accounts from the Hannibalic War period illustrate the Senate’s commanding role in both military strategy and Mediterranean diplomacy, a capacity Polybius admired as the Republic’s most refined constitutional moment. Institutional reforms also regulated the nobilitas, curbing electoral excesses and codifying senatorial advancement, while reinforcing the internal hierarchy dominated by consulares.

However, this golden age was later viewed through a nostalgic lens, with Sallust describing it as a time of moderation and harmony. Its decline began with the rise of the populares after 133 BCE, whose legislative victories against senatorial will, judicial reforms, and use of political violence fractured elite consensus and marginalized the Senate’s role—especially in foreign affairs.

In response, the Senate developed tools such as the senatus consultum ultimum, claiming a renewed moral authority in times of crisis. The expansion of Rome's empire both enabled and undermined senatorial power. Sallust and Cassius Dio identified growing wealth disparities, institutional strain, and the Senate’s inability to govern an expanding empire as root causes of systemic dysfunction.

Sulla’s later reforms aimed to restore senatorial supremacy by weakening the tribunes and enlarging the Senate, but the influx of less experienced members diluted its cohesion. From 70 to 50 BCE, the Senate continued to assert itself, especially in foreign policy and legal definitions of public enemies, even as military strongmen like Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar bypassed its authority.

Despite its diminishing power, the Senate’s symbolic value endured. The senatus consultum ultimum remained a potent ideological tool, and figures like Caesar still paid rhetorical homage to the Senate’s auctoritas.

Tacitus later reflected this continuity when he portrayed Emperor Otho framing the Senate as the custodian of the Republic’s legacy. Ultimately, as Talbert notes, the Senate did not dissolve into irrelevance with the end of political liberty, but instead adapted, preserving its prestige through ritual, symbolism, and tradition. ("The Senate" by Marianne Coudry, in "A Companion to the Political Culture of the Roman Republic")

The Illusion of Recovery: Sulla’s Legacy and the Senate’s Last Struggle for Coherence

Despite the apparent restoration of senatorial supremacy after 70 BCE, deeper structural weaknesses remained. The expansion of the Senate under Sulla had brought with it an unintended consequence: a sharp division between ambitious office-holders and a larger body of men whose public role consisted only of jury duty and debate attendance.

This bifurcation weakened cohesion and diluted the Senate’s functional capacity. Many of Sulla’s appointees never progressed beyond the quaestorship, creating what some scholars describe as a senatorial “penumbra” — a silent majority excluded from true political power.

Even the return of the tribunate and the harsh censorial purge of 70 BCE, which expelled dozens of senators, failed to address the imbalance. The Senate remained a bloated, uneven body, unable to act decisively as factionalism deepened.

Procedural inefficiency, bribery, and political gridlock became common. Though it retained its outward grandeur, the institution had begun to hollow from within — a fate sealed not by a single event, but by an accumulation of design flaws that even tradition could no longer conceal. (From Ascendancy to Adaptation: The Senate's Journey Through the Middle and Late Republic, by Catherine Steel)

Was the Roman Senate Still Powerful Under the Emperors?

Between 30 BCE and 238 CE, the Roman Senate underwent significant transformation. The former date marks Octavian’s consolidation of power after years of civil war and his eventual rise as Augustus, initiating the Principate. The latter year, 238 CE, represents a natural stopping point, as literary sources grow sparse and the Empire enters a phase of exceptional instability, leading to a restructured imperial system.

During this period, the Senate’s membership evolved, and senators took on varied official responsibilities under imperial oversight. Although many scholars have explored individual careers and the Senate’s relationship with the emperor, less attention has been paid to how the Senate functioned as a collective institution during the Principate.

This aspect has remained understudied, with few comprehensive works dedicated to its procedural operations. Even in the 19th century, while T. Mommsen addressed senatorial activity within his broader constitutional study, he largely dismissed the Senate’s imperial role, convinced that the Roman state had become “utterly withered and dead” following Caesar’s dictatorship.

Later reference works likewise neglected the corporate functions of the Senate in this era or treated them only briefly and without detail. The decline of the Senate’s authority during the Principate is undeniable. The erosion of its political power had begun in the late Republic but became lasting and systemic under imperial rule.

The institutional downgrading was compounded by a severe loss of source material: the acta senatus, the Lex Julia de senatu habendo from 9 BCE, most senatus consulta, and the legal commentaries on these acts are all largely lost. Few senatorial speeches have survived in full, and no complete record exists of the proceedings from a single meeting, leaving the scope and variety of Senate business difficult to reconstruct.

Yet, despite the curtailment of its autonomy and prestige, the Senate did not fade into irrelevance. Its persistence in a diminished but still operational capacity represents a notable historical paradox. In many ways, the Senate of the Principate resembled other constrained political bodies in ancient and modern history, limited in authority but institutionally resilient.

Though the source material is fragmentary, the available evidence for the Senate’s procedures during the first and early second centuries CE is surprisingly rich. In contrast to the Athenian Assembly, whose workings are largely known through outcomes rather than processes, the Senate of this period benefits from descriptive accounts by Tacitus and Pliny the Younger.

Pliny detailed meetings he personally attended, while Tacitus, it is argued, drew heavily from the acta senatus, established in 59 BCE. Although this record no longer survives, Tacitus’ accounts may offer a reflection of its structure and content. Other literary sources—Seneca, Fronto, Dio Cassius, and the imperial biographies of Suetonius and the Historia Augusta—also shed light on the Senate’s dynamics and the emperor’s stance toward it.

Non-literary sources add further depth. Coins, papyri, legal texts, archaeological finds, and inscriptions—particularly those uncovered during the 20th-century restoration of the Curia Julia—offer additional data.

Epigraphic material on senatorial activity is especially abundant, though previously uncollected and unanalyzed in a focused manner. Legal texts, while often fragmentary, contain excerpts from jurists active between 100 and 250 CE, providing considerable information about the legislative output of the Senate.

From Census to Curia: Who Could Enter Rome’s Senate Under the Emperors?

Understanding the operation of the Roman Senate during the Principate begins with knowing who its members were, how they were chosen, and what rules governed their entry and progression. Admission was restricted to freeborn Roman citizens of sound standing:

—“conviction under the Lex Julia de vi privata barred a man from any position of honor or responsibility, including membership of the senate.”

Marcianus

Marcianus was a Roman jurist from the early 3rd century CE. (he is the source for this legal stipulation, which appears in the Digest of Justinian, a 6th-century compilation of earlier Roman legal writings — Marcianus' work, often excerpted in the Digest, addressed senatorial eligibility and legal restrictions such as those imposed by the Lex Julia de vi privata — a law concerning private violence)

Physical condition mattered as well: Ulpian (a Roman jurist) asserted that:

“a blind man could not seek any further office”

Though he could retain his rank. Augustus introduced two notable changes around 18 BCE: raising the property qualification to one million HS, (HS stands for sestertius (sestertii in plural), a common unit of Roman currency — the abbreviation HS comes from the Latin "HS" or "IIS", which stood for "duo et semis", meaning "two and a half" — a reference to its original value of 2.5 asses (another Roman coin).

Dio observed that:

“even the sons and grandsons of senators…not only would not lay claim to senatorial dignity, but also if chosen rejected it on oath.”

Despite these restrictions, emperors often helped promising individuals bridge the gap.

“For most of them he [Augustus] made up the required census,”

Cassius Dio, Book 54, Chapter 17, Roman History

and later emperors followed suit. While access was largely through magistracies such as the vigintivirate and the quaestorship, emperors could also use adlection—granting rank without the need for election.

Claudius, the first emperor known to have used this method, did so sparingly. Later emperors, like Vespasian and Domitian, used it more freely but never to “pack” the Senate with loyalists. Even so, as early as Gaius’ reign, there existed a recognizable “senatorial class,” shaped by imperial favor, aristocratic networks, and carefully preserved traditions. (The Senate of Imperial Rome, by Richard J .A. Talbert)

Across the centuries, the Roman Senate weathered conquest, civil war, and constitutional upheaval. From its origins as a royal council to its transformation under emperors, it adapted—sometimes reluctantly, often imperfectly—but never disappeared. Though stripped of legislative supremacy and relegated to the margins of real power, it continued to perform ritual, confer legitimacy, and represent the memory of republican ideals.

The emperors who sidelined it still addressed it, adorned it, and, when convenient, feared its judgment. In the end, the Senate survived not by command but by continuity—its very presence reminding Romans that authority could evolve, but tradition never truly vanished.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: