The Elderly in Ancient Rome: Voices of Respect and Fear

Old age in Rome was both feared and revered. Cicero praised its dignity, Juvenal mocked its weakness, and proverbs marked sixty as the threshold of decline. Between honor and ridicule, the elderly lived at the margins of Roman society.

To live long could mean reaching a place of honor, wisdom, and influence; but it also brought frailty, dependence, and, at times, ridicule. Roman literature and law reveal a society that grappled with aging as both a natural stage of life and a social problem, where the elderly could be revered in the Senate or dismissed as useless in the household.

Cicero wrote in De Senectute,

“Old age, cannot be held against me, for I have loved it and embraced it.”

Yet for many Romans, growing old was a condition both respected and feared.

How the Ancient World Saw Its Elders

Old age in antiquity has long remained in the shadows compared to the study of childhood or youth. Ancient sources mostly celebrated men in their prime, while the elderly appeared only at the margins—as curiosities, moral examples, or objects of satire.

Lists of the long-lived, such as those promised by Pseudo-Lucian or cited by Cicero, focused more on wonder than reality, and even these contained few Romans. The neglect of old age is striking given that Romans did live long lives, though their experiences often remain invisible in the surviving evidence.

Modern scholarship has begun to challenge this silence, drawing attention to demographic, social, and cultural realities. Yet the literary record is problematic: old age is usually mentioned through stereotypes, rhetorical topos, or for didactic purposes rather than as lived experience. Cicero might defend aging as a season of dignity, while Juvenal mocked it as weakness—neither reflecting the full complexity of real lives.

“Old age is the final act of life’s drama, full of dignity, if only it be well played.”

Cicero, De Senectute

“Old age is the most dreadful of all evils; it deprives us of everything, even of the power of enduring itself.”

Juvenal, Satires

Older people must not be seen as isolated, but as integral to Roman society.

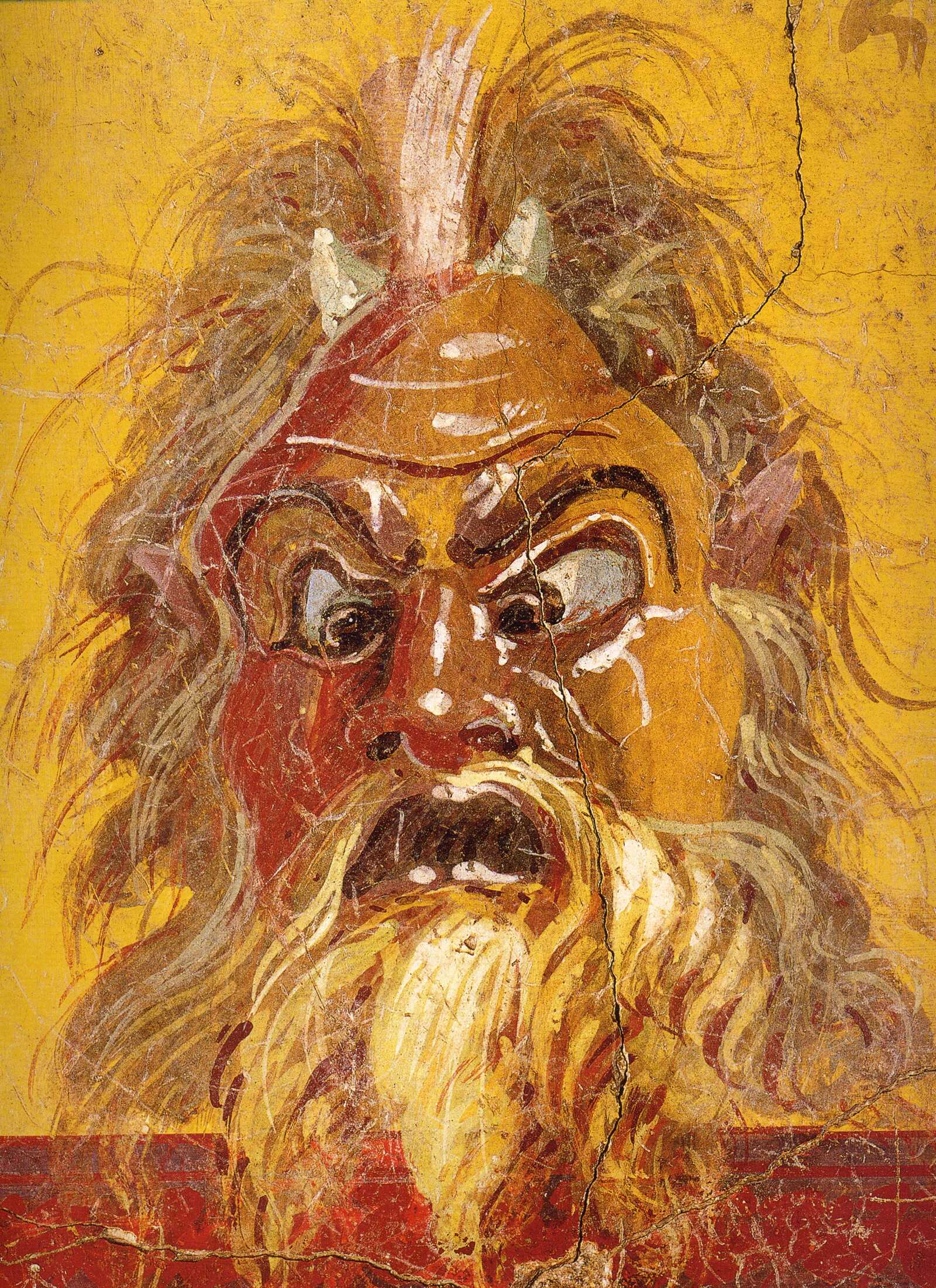

A fresco of a theatre mask of an old Satyr, in Pompeii. Public domain

The challenge for historians lies in piecing together scattered literary references with legal texts, inscriptions, and papyri to form a more nuanced picture. Their roles, whether as dependents, active participants in public and private life, or marginalized individuals, reflect broader cultural attitudes.

Questions arise about how the state responded to their needs, how families treated aging parents, and how gender shaped the experience of growing old. Women, though less visible in the sources, played essential roles within the household as they aged.

The reality of old age varied greatly—by time, place, and individual circumstance—and cannot be captured by any single definition. Evidence is uneven and shaped by authors’ intentions, political contexts, and cultural expectations.

Anecdotes highlight unusual or remarkable cases, not typical patterns. Epigraphic sources, like tombstones recording age at death, offer some clues, though they too are shaped by convention and selective memory.

Ultimately, studying old age in Rome is not only about reconstructing the physical and social reality of senectus but also about understanding attitudes toward the elderly and how society at large perceived and positioned them. The subject remains important both for what it reveals about Roman society and for the reflections it provokes about our own treatment of aging.

The Elusive Boundaries of Roman Old Age

When did the Romans consider someone “old”? Two millennia later, the answer remains elusive. The Greeks and Romans had plenty of words to describe aging: in Latin, senex meant “old person,” while senectus denoted “old age.” In Greek, the equivalents were γέρων and γῆρας, both derived from the Indo-European root ger-, meaning “to grow old.”

These words also gave rise to familiar Roman terms, from senatus (the senate, literally “the council of elders”) to the philosopher Seneca’s very name. Yet while the vocabulary is clear, defining its limits in terms of years is far more complicated.

Even today, chronological age and biological age rarely align. Someone may appear young or vigorous well into advanced years, while another person might be frail before middle age. The same held true for the Romans. Institutions like retirement or social welfare, which help modern societies anchor concepts of old age, had no direct equivalent in Rome. A figure of sixty or seventy might serve as a convenient dividing line for us, but no universal definition applied in antiquity.

Some scholars have suggested that Romans grew old unusually early. One ancient comment held that “the average life was short—it was a young man’s world,” and that senex could be used for anyone over forty. By modern standards, this seems remarkably young. Others, more convincingly, place the beginning of senectus at sixty. The tension between forty and sixty is significant, for it reveals how flexible and situational the label of “old” could be.

The literary topos of the “ages of man” provided some guidance. From Solon through Shakespeare, writers divided life into three, seven, or even ten stages. Hippocratic texts, for example, counted life in seven-year blocks, beginning old age variously at forty-two, fifty-six, or sixty-three.

Claudius Ptolemaeus, writing in the second century CE, described the ages of man according to planetary influences, with old age commencing at sixty-nine. Censorinus, in the third century CE, preserved a Roman scheme of five ages, aligning Varro’s fourfold division of Rome’s history with the onset of senectus at sixty. Saint Augustine even commented that:

“old age may be said to begin from the sixtieth year.”

These overlapping systems show how Romans inherited and adapted Greek traditions, especially the Hippocratic scheme. Yet no single arrangement prevailed. Senectus could begin as early as forty-two or as late as seventy-seven. Aulus Gellius observed wryly that:

“the world itself seems to be aging” (quasi iam mundo senescente)

Horace labeled the satirist Lucilius a senex at forty-five. Martial prayed for eighteen more years of life at age fifty-seven, hoping to reach seventy-five “not yet slowed down by excessive old age.” Such examples reveal not a fixed standard but a range of personal and cultural expectations.

“So that, not yet slowed down by excessive old age, but with three circuits of life’s course completed, I may seek the groves of the Elysian girl. Beyond this ‘Nestor’ of an age, I shall not ask for even another day.”

Martial, Epigrams

Statements of age appear constantly in Roman sources, but their reliability is uneven. Tombstone inscriptions, for example, often rounded ages up or down to the nearest multiple of five. In Noricum, Celtic epitaphs regularly listed deaths at exactly 50, 60, 70, or 80 years.

In Roman Africa, exaggerations of extreme longevity were frequent, with supposed centenarians far more common than statistical reality allows. Historian A. R. Burn, analyzing 2,675 inscriptions, found that almost two-thirds of the ages ended in either X or V, suggesting conventional rounding rather than precise reporting.

This imprecision extended even to the elite. Julius Caesar’s birth year remains debated: Appian claimed he died in his fifty-sixth year, while Plutarch wrote he was fifty-six, when by our reckoning he was fifty-five. Augustus, too, was sometimes said to have turned sixty-three when in fact he was sixty-four. Suetonius gave contradictory reports for Tiberius’s birth year. Even Cicero’s age at death appears inconsistently, though he himself often described others as senes or adulescentes without rigid calculation.

The Roman legal system occasionally imposed fixed age thresholds, but even here ambiguity lurked. Ulpian stated that a man was twenty years old on the last day of his twentieth year—effectively an official reckoning method that could differ from ordinary understanding.

He also held that boys under seventeen (pueri) were excluded from legal petitions, while those over seventy were exempt from certain civic duties. But such boundaries were rare exceptions. For most Romans, age was fluid, judged more by appearance, vigor, or social role than by the calendar.

A further complication lies in ancient reckoning systems. In Egypt, ages could be calculated inclusively, so that a child in his fourth year might only be three by modern count. Inconsistencies multiplied across provinces: papyri from Antonine Egypt record children as four when by strict arithmetic they should be three.

Tombstone formulas like sexaginta annos natus (“sixty years old”) might in practice mean fifty-nine completed years. Bureaucratic needs, especially in taxation or military service, forced officials to assign ages, but the methods varied.

Underlying all this was a Roman indifference to precise age. Most people did not know their exact year of birth, and few felt the need to. Knowledge of one’s dies natalis (the day of birth) mattered less than the associated cult of one’s genius or Iuno.

Juno (Iūnō) was the female counterpart. Every woman was believed to possess her own Juno, just as every man had his Genius. While the man’s genius expressed his generative and protective essence, the woman’s Juno embodied her capacity for fertility, marriage, and protection.

So in Roman thought:

Genius = a man’s guiding/life spirit.

Juno = a woman’s guiding/life spirit.

This is why dedications sometimes read Genius of So-and-so (for men) and Juno of So-and-so (for women).

For the majority, it was enough to be broadly identified as young, middle-aged, or old. The exception was in legal or administrative contexts, where rules of age for marriage, manumission, or military service required calculation.

Even then, results could be inconsistent or open to doubt. Pliny the Younger once described a case where Regulus, a notorious legacy-hunter, tried to calculate a widow’s age for inheritance purposes, and even there the estimates varied wildly between forty and sixty.

The Marginality of Old Age

In Roman thought, old age hovered uneasily between reverence and rejection. Cicero defended it in De Senectute, insisting it could be a time of dignity, yet his very arguments reveal how deeply negative perceptions ran. To many, the old stood apart from the civic core of adult male life. Literary tradition often cast them as excluded:

“The young men go out to fight while the women, children, and elderly are left behind at home,”

noted one writer. Quintilian observed that in court:

“old men, women, and children”

were displayed to stir pity,

“even in a rectus iudex.”

Livy recorded the plight of a veteran,

“covered in scars, now impoverished, dragged to prison, and beaten,”

whose suffering sparked revolt. Ovid, blunt as ever, declared:

“An old soldier is a disgusting thing.”

Mockery was never far away. One description of an elder in public life ran:

“If the old man has the audacity to enter the agora, he provokes the laughter of those who see him, for he cannot see properly and cannot hear when people shout. Trying to make his way forward he trips and falls. He is accused of getting in the way and of spoiling the common air of the city.”

Aesop’s fable of the lion,

“worn out through years and bereft of strength,”

who is beaten by smaller beasts, carried the same moral.

Philosophers and satirists amplified this image. Aristotle placed the old alongside minors, exiles, and the disenfranchised as lesser citizens. Horace labeled Lucilius a senex at forty-five. The elegist Maximianus poured out the most bitter lament:

“Insults, contempt, and violent losses follow… The very boys and girls themselves think it disgusting to call me now their master. They snigger at my gait, they even snigger at my face, and my trembling head, which once they feared.”

Women fared worse. Past childbearing, their social role evaporated. Literature painted them as grotesque, lustful, or cruel. Ovid’s curse captures the disdain:

“May the gods grant you no home and a needy old age and long winters and everlasting thirst.”

Catullus lashed at an old woman as “a toothless crone.” Juvenal conjured them as witches brewing potions, while Varro spoke of the “old hag” as a stock figure of ridicule.

Medicine mirrored these anxieties. Hippocrates declared:

“In the prime of life everything is lovely, in the decline it is the opposite.”

Some physicians flatly described old age as a disease. Galen resisted, insisting:

“Old age is not a disease; it is a natural process.”

Still, he conceded it was:

“no state of health,”

only the gradual waning of powers.

Religious life offered limited compensation. Plato and Aristotle both judged old men particularly suited to ritual. In Rome, the paterfamilias presided over household rites, while priesthoods could be held for life. Yet here too the old were measured by usefulness: only if they could perform their duties were they allowed to continue.

The darkest themes appear in stories of senicide. Ancient writers relished tales of distant peoples who killed their elderly.

“The Hyperboreans sent the old away at sixty.”

“The Ligurians hurled parents from cliffs.”

“The Caspians starved them to death.”

“The Massagetae slaughtered them like cattle.”

Lactantius repeated such reports, while Procopius told of tribes who exposed their old to dogs. These were labeled barbaric, yet Roman fascination with them betrayed deep unease.

Closer to home stood the proverb sexagenarios de ponte — “sixty-year-olds from the bridge.” Some took it literally, imagining that at sixty men were hurled into the Tiber. Ovid objected:

“He who believes that after sixty years men were put to death, accuses our forefathers of a heinous crime.”

Others thought it meant political exclusion — that after sixty, men lost their vote and were symbolically “cast from the bridge” of the assembly. Either way, the saying marked sixty as the threshold of decline.

Cicero admitted the danger of disdain:

“Old men risk being shunned, treated with scorn and contempt.”

Maximianus echoed the same centuries later:

“Though I can see nothing, yet this I may behold — so it makes that penalty itself harder for me, poor wretch, to bear.”

Thus old age in Rome was marked by contradiction. It could confer memory, counsel, and religious authority, yet it also carried the stigma of weakness and decline. Elders might be praised for wisdom, but just as often they were mocked for frailty, standing always on the threshold between honor and neglect.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: