Plutarch: A Greek Voice in the Heart of Rome

Plutarch, the Greek historian, biographer, and philosopher, wrote in an era when Rome dominated the Mediterranean world, yet his works found an eager audience among the very people who had conquered his homeland.

Plutarch’s Parallel Lives offered moral reflections wrapped in compelling biographies of Greek and Roman figures, while his Moralia provided philosophical guidance that resonated with Rome’s intellectual elite.

Though deeply rooted in Greek traditions, Plutarch shaped the Roman understanding of their own history and virtues, bridging the cultural divide between Greece and Rome. His writings not only entertained but also instructed, offering the Romans a mirror through which they could measure their own greatness against the legends of the past.

Why did Plutarch’s works captivate his Roman readers, and how did they interpret his lessons? The answer lies in the complex interplay of admiration, identity, and the enduring influence of Hellenic thought on the Roman world.

Between Two Worlds: Plutarch’s Greek Identity and Roman Engagement

No other writer bridged the worlds of Greece and Rome as successfully as Plutarch. His greatest work, Parallel Lives, honors the virtues and legacies of both civilizations by drawing comparisons between their heroes and histories. His deep understanding of each culture and its influence on the broader world won him fame in his own time and secured his reputation as a key figure in classical literature. But how did a Greek intellectual come to speak so authoritatively about Rome?

Plutarch was born in Chaeronea, a city long under Roman rule by his time. His homeland had been the site of pivotal battles—where Philip of Macedon defeated the Greek coalition in 338 BCE and where, centuries later, Sulla crushed the forces of Mithridates in 86 BCE, securing Rome’s dominance over Greece. The relics of these conflicts, from monuments to buried weapons, were tangible reminders of his city's turbulent past.

Roman authority was not always benign. Chaeronea itself narrowly escaped destruction when an altercation between a young local and a Roman officer nearly led to its downfall—only intervention by Lucullus, an officer under Sulla, spared it. Plutarch's own family had endured Rome’s demands; his great-grandfather was forced to carry grain for Mark Antony’s troops before the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. Rome’s rule was an unchallenged reality in Plutarch’s life, yet its governance remained unstable, culminating in the civil war of 69 CE, which he witnessed firsthand.

Despite this, Plutarch’s intellectual world was deeply Greek. His education in rhetoric, philosophy, and history, his priesthood at Delphi, and his reverence for Greek literary tradition—particularly Plato—defined his scholarly identity. He was among the earliest figures of the Greek literary revival of the second century CE, yet unlike his contemporary Dio of Prusa, he chose to define himself as a philosopher rather than an orator.

What set Plutarch apart from other Greek intellectuals of his time was his profound knowledge of Roman history, politics, and institutions. Plutarch’s engagement with Rome was deliberate and highly successful.

His teacher in Athens, Ammonius, who held the office of Herald of the Areopagus, frequently interacted with Roman officials, perhaps inspiring Plutarch to pursue ties with the empire. An essential moment may have been Nero’s visit to Greece in 68 CE, when the future emperor Vespasian was among the entourage. Plutarch writes of attending the games at Delphi with Ammonius, where he may have encountered influential Romans.

Shortly after Vespasian became emperor in 69 CE, Plutarch likely traveled to Alexandria as part of a diplomatic mission. There, he met Lucius Mestrius Florus, a senator and close associate of Vespasian, who would become his patron and benefactor. Florus granted him Roman citizenship, giving him the name Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, and secured his place within the equestrian class. This prestigious connection not only elevated Plutarch’s status but also facilitated his introduction to Rome’s political elite.

By the early 70s CE, Plutarch traveled to Rome, where Florus took him to northern Italy. Plutarch proudly recalls visiting the battlefield of Bedriacum and Otho’s monument at Brixellum, sites significant in Rome’s recent civil war. Florus’s patronage provided Plutarch with access to leading senators and, crucially, the emperor himself. Through these connections, he positioned himself as a Greek intellectual uniquely fluent in Roman history and political culture, securing his legacy as an enduring bridge between the two great civilizations.

Credits:

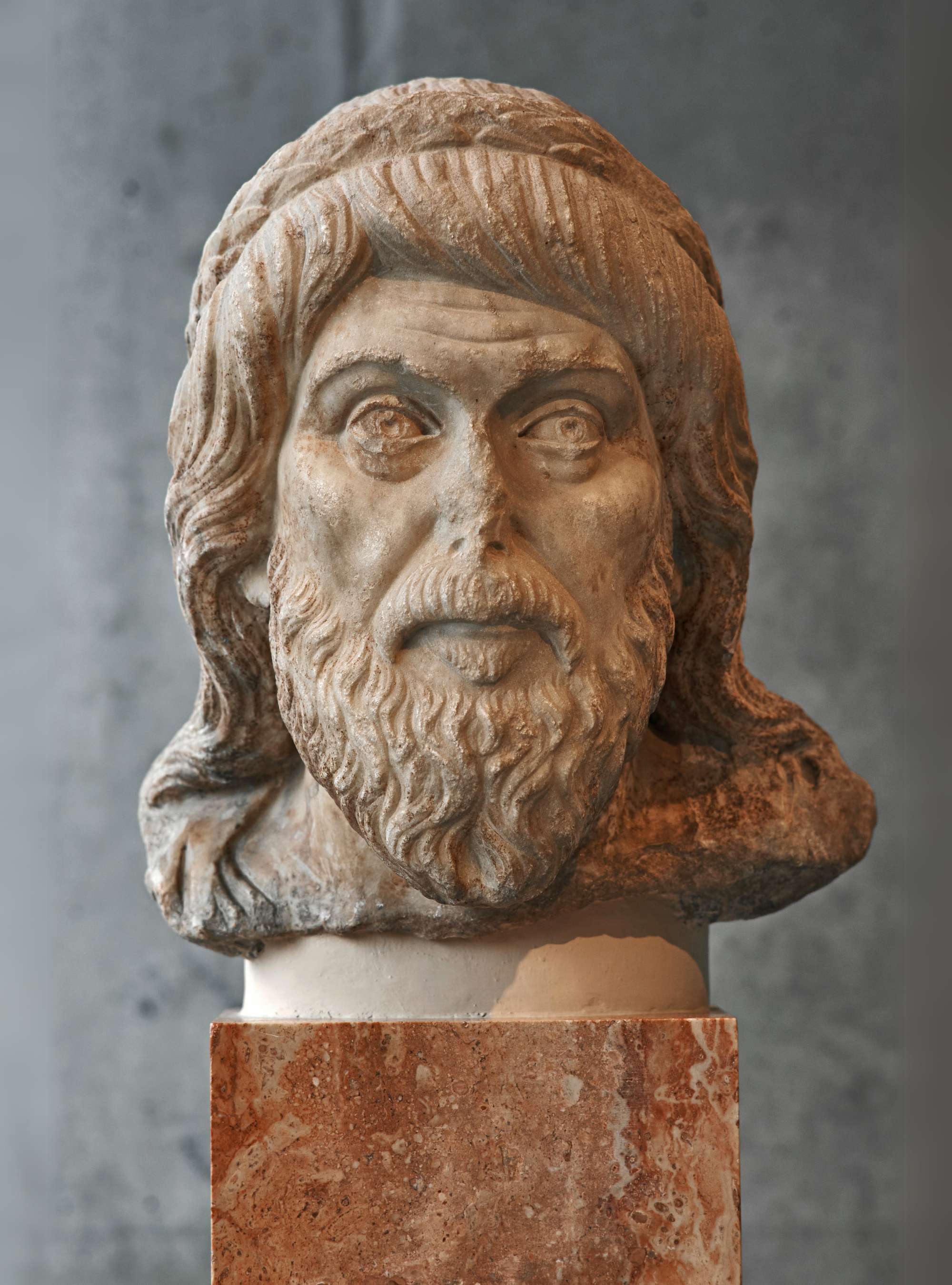

#1: Giannis Giannakitsas, Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

#2: Philipp Pilhofer, CC BY-SA 3.0

Plutarch in Rome

Plutarch’s initial visit to Rome served multiple purposes: establishing his reputation as a philosopher and speaker, advocating on behalf of his fellow citizens from Boeotia or Delphi, and expanding his network of Roman acquaintances. As he later reflected:

“While I was in Rome and other parts of Italy, I did not have leisure to practice the Latin language on account of political business and people coming for philosophy.”

This suggests that he gave lectures on philosophical topics, similar to the philosopher Euphrates, whom Pliny the Younger admired. It is likely that these lectures were delivered in Greek. Among his audience was probably his patron, L. Mestrius Florus, who had a keen interest in philosophical discussions and regularly celebrated the birthdays of Socrates and Plato. Another influential Roman connection was Julius Secundus, a notable speaker during Vespasian’s reign.

Although Plutarch does not specify his political engagements in Rome, they may have been related to Delphi. Vespasian granted Delphi the status of a free and autonomous city, along with other privileges. Plutarch may have also played a role in securing the appointment of Vespasian’s son, Titus, as archon (chief magistrate) of Delphi, a prestigious position that Titus held while serving as emperor in 79/80 CE, coinciding with the Pythian Games.

Plutarch’s time in Rome also allowed him to develop reading and possibly speaking fluency in Latin. By the time he composed the Lives of the Caesars, likely in the mid-70s, he was already able to engage with Latin historical sources, some of which were later used by Tacitus and Suetonius. While he may have begun studying Latin in Chaeronea or Athens, his mastery of the language intensified as he expanded his intellectual and political engagement with Rome.

He later wrote:

“I began to read Roman works late and when advanced in age”

Implying that his deep engagement with Latin texts came only after years of Greek scholarship. He explained his method of learning:

“It happened that I followed along the words from the circumstances, insofar as I had some experience of them, rather than understood and recognized the circumstances from the words.”

However, he admitted that he never mastered Latin rhetoric to the level of native speakers, stating:

“I think it charming and pleasurable to perceive the beauty and rapidity of Latin delivery and the stylistic figures and rhythms and the other features in which it glories, but practice and exercising for this purpose was not convenient: that is more for those whose greater leisure and suitable age permit such ambitions.”

Despite his humility, Plutarch’s extensive engagement with Roman historians and literature demonstrates his fluency rather than difficulty in reading Latin.

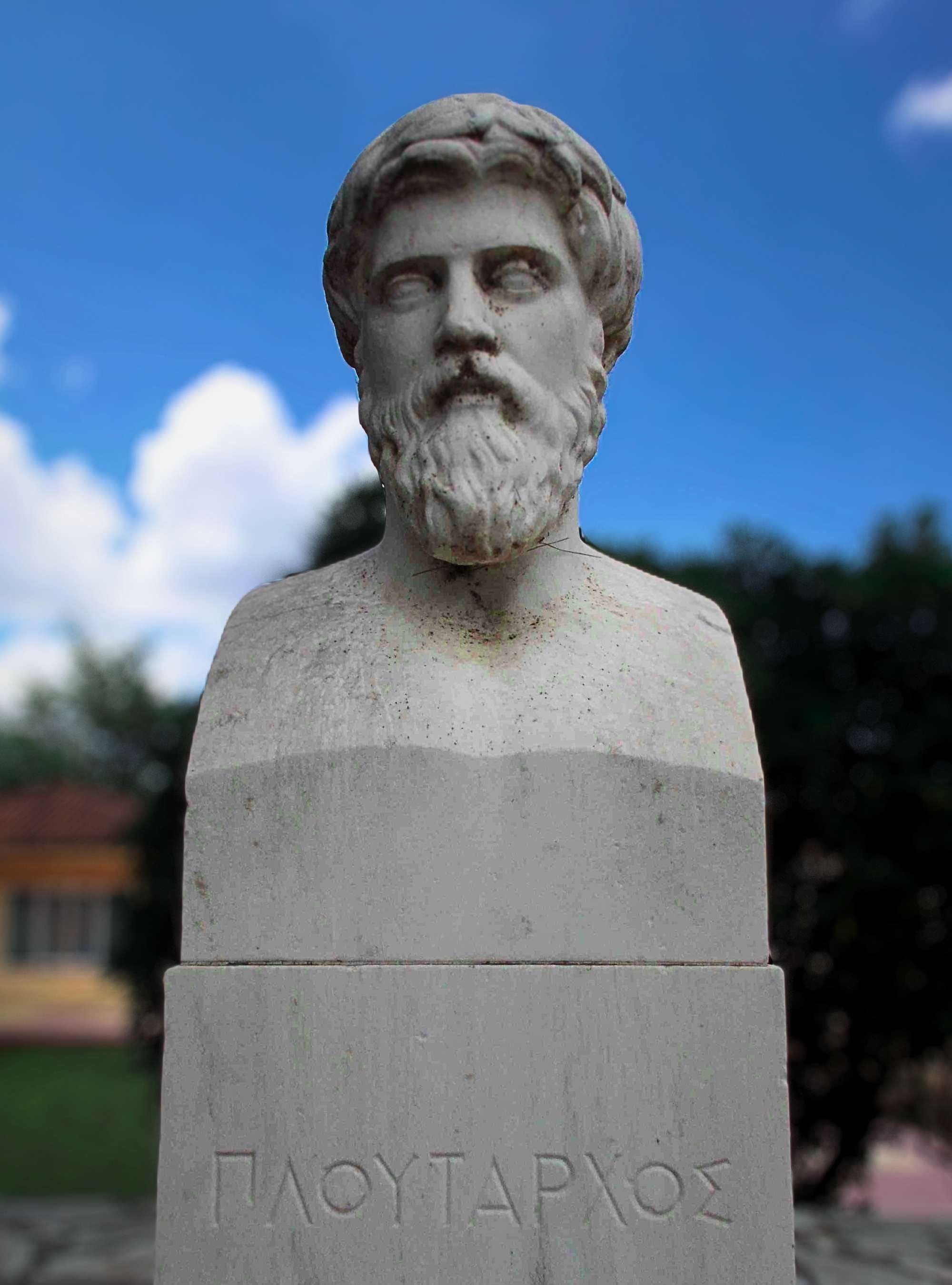

A portrait of Plutarch. Credits: Wellcome Images, CC BY 4.0

Beyond written sources, Plutarch’s interactions with Roman senators and intellectuals enriched his understanding of Roman history and culture. His speech On the Fortune of the Romans, likely delivered in Rome under Vespasian, reflects an impressive knowledge of Roman history from Romulus to Augustus, drawing upon sources like Valerius Antias and Livy.

His familiarity with Roman customs was further deepened by his travels through Italy with Florus, which allowed him to visit battlefields and significant historical sites. His deep engagement with Rome continued in later works.

The Roman Questions, written after the death of Domitian in 96 CE, showcases Plutarch’s thorough study of Roman customs, history, and antiquarian traditions. Drawing on authors such as Varro and Verrius Flaccus, he sought to explain Roman rituals and practices in a way that resonated with Greek philosophy.

Rather than portraying Roman traditions as inferior or irrational, he highlighted their underlying wisdom, occasionally even preferring them over Greek customs.

An engraving on laid paper of Plutarch, by Léonard Gaultier. Credits: National Gallery of Art, CC 1.0

Over the years, Plutarch likely visited Rome multiple times, possibly in 89 CE and again in 92 CE. After that, no records confirm his presence in the city, though Domitian’s expulsion of philosophers in 93 or 94 CE may have played a role in keeping him away. During his visits, he may have represented Delphi before Domitian, who restored the grand temple of Apollo in 84 CE.

Plutarch also continued to teach philosophy, as seen in an anecdote where Iunius Rusticus, a Stoic senator and former consul, attended one of his lectures. Rusticus was handed a letter from Domitian mid-lecture but chose to finish listening before reading it—a display of Stoic restraint that Plutarch admired. Unfortunately, Rusticus later fell victim to Domitian’s tyranny and was executed for his opposition to the emperor.

Plutarch and the Emperors

The Roman emperor stood at the pinnacle of society, and Plutarch, through his connections, had access to the imperial circle. He may have first encountered Vespasian in Alexandria, and his friendship with L. Mestrius Florus linked him directly to the emperor’s inner circle. Encouraged by these relationships, he embarked on a major literary project: Lives of the Caesars, a collection of biographies covering the reigns of emperors from Augustus to Vitellius (31 BCE–69 CE).

Though only the Lives of Galba and Otho survive, the original work was an ambitious endeavor, spanning at least 375 modern pages, possibly 500. It was also the first known work to present Roman history as a series of biographies, emphasizing the character and actions of individual rulers. This approach influenced later historians, including Suetonius and the authors of the Historia Augusta, while even Tacitus structured his historical narratives around the reigns of emperors.

Plutarch approached history with a philosophical lens, focusing on moral values and just governance, principles that appear frequently in his essays and dialogues. He embraced the Platonic ideal of a ruler dedicated to the well-being of his people, promoting justice, harmony, and peace. As he wrote in Dion:

"He would conform his character to the principle of virtue and render it similar to the most divine and holy model of reality which guides the universe from disorder to order, and thus would procure great happiness for himself and his citizens.

He would achieve by his paternal rule, through self-control and justice and with the goodwill of his subjects, what [before] had been obtained from their discouragement and oppression, so that he would be a king rather than a tyrant."

The Lives of the Caesars provided an opportunity to assess this ideal in reality. In the introduction to Galba, Plutarch invokes Plato’s Republic to describe the anarchy of the civil war: soldiers running amok, severed heads displayed, and tyrants rising and falling in quick succession—“the complete breakdown of rational government.” By contrast, Augustus, at least in his later years, embodied the Platonic ideal.

Though he had been as ruthless as any ruler during the civil wars, he ultimately became a stabilizing force. Plutarch later reflected that his policies:

“became much more kingly and helpful to the people toward the end of his life” (An seni 784D)

(An seni 784D- refers to a passage from Plutarch's Moralia, specifically from his essay An Seni Respublica Gerenda Sit — Whether an Old Man Should Engage in Public Affairs). This portrayal positioned Augustus as the wise ruler who restored order, in stark contrast to the chaos of Galba and Otho’s reigns.

Though most of the other Lives are lost, Plutarch’s opinion of Nero survives. He acknowledged Nero’s proclamation of Greek freedom in 68 CE but dismissed any lasting virtue in him. According to Plutarch, Nero’s crimes, especially his murder of his mother, condemned his soul to reincarnate as:

“a frog in a swamp rather than as the viper his actions deserved.”

The trajectory of the Caesars suggested a steady decline from Augustus' rule to the anarchy of 69 CE, and Plutarch likely viewed Vespasian’s reign as a necessary renewal for Rome. However, he remained realistic about imperial rule, recognizing that emperors rarely embodied the philosopher-king ideal. His work subtly implied that the Roman ruling class required moral guidance—perhaps even from a philosopher like himself.

Plato had attempted to educate the rulers of Syracuse, and Plutarch, through his Roman friendships, might have envisioned a similar role for himself. Writing historical biographies that instilled political morality was his first step in that direction.

Despite his philosophical ambitions, Plutarch acknowledged Vespasian’s shortcomings. He criticized the emperor for his harshness toward the wife of a Gallic rebel, the mother of a friend in Delphi, though he also recognized his good fortune. His diplomatic skills may have influenced Vespasian’s son Titus to serve as archon of Delphi and Domitian to restore Apollo’s temple.

However, Plutarch later criticized Domitian's excesses. He noted wryly that the emperor named two months after himself:

“but not for long: they resumed their names again after his assassination.”

In Publicola, Plutarch condemned Domitian’s extravagant palace on the Palatine, suggesting that someone might say to the emperor:

“You aren’t pious or liberal, you are diseased: you delight in building; just like Midas you want everything to be in gold or stone.”

This mirrored an earlier passage in Solon, where Solon, upon seeing the court of King Croesus:

“ remained unmoved by the spectacle … he actually despised the vulgarity and petty ostentation of it all”.

The scene likely reflects Plutarch’s own experience in Domitian’s lavish Domus Flavia.

A reconstruction sketch of how Domus Flavia looked like, belonging to Roman Emperor Domitian. Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

Despite his disdain for tyranny, Plutarch followed Solon’s example by continuing to engage with rulers rather than opposing them outright. The Parallel Lives were not written until after Domitian’s death, suggesting that Plutarch believed the emperor’s absolutism would not have tolerated the critical perspectives he had exercised in Caesars.

Though no evidence links Plutarch directly to Nerva, he had strong ties to Trajan’s inner circle, particularly Sosius Senecio, a close advisor to the emperor. He even wrote for Trajan a collection of historical anecdotes, Sayings of Kings and Commanders, which he dedicated to the emperor with these words:

“These expressions and utterances, like mirrors, give the opportunity to observe the mind of each statesman.”

This work aimed to provide Trajan with moral and political inspiration. However, Plutarch may have been disappointed that the emperor preferred short anecdotes over his deeply researched Lives. Although Plutarch shared many of Trajan’s ideals of governance, the emperor seemed more preoccupied with his Dacian and Parthian wars than with philosophical reflections on leadership.

Whether due to Senecio’s influence or Trajan’s own recognition of Plutarch’s work, the emperor honored him with the ornamenta consularia, granting him the rank and privileges of a Roman consul. This prestigious recognition elevated him to a position of great respect within the empire. A later, less reliable source suggests that Hadrian appointed Plutarch as imperial procurator for Greece, though this might have been a more symbolic role. (Plutarch in Context, by Philip A. Stadter)

Bridging Two Worlds: Plutarch’s Greek Identity and Roman Engagement

Plutarch was a Greek by birth, a lifelong resident of Greece, and a writer who composed all his known works in Greek. Yet, he lived in a world where Greece had been under Roman rule for ten generations. Over time, Rome had absorbed much of Greek culture, while the Greeks, though slow to embrace Roman ways, found means of coexistence under imperial governance.

The Romans preferred a stable elite and sought to maintain peace among Greek cities rather than impose heavy-handed oppression. However, power could always turn brutal, as Plutarch well understood. His own great-grandfather, Nicarchus, had suffered under Roman demands, forced to carry grain for Antony’s army under the lash.

Unlike the rapid Romanization of Gaul or Spain, the Greeks held firmly to their own language, literature, and traditions, using their cultural legacy both as a source of identity and as a means of earning Roman respect. Romans themselves, from Aemilius Paullus to Cicero and Pliny the Younger, admired Greek learning, recognizing it as the foundation of humanitas.

As a result, Greek intellectuals remained committed to writing and speaking in a pure, classical Greek style, considering it the hallmark of true education. By the late first century AD, a resurgence in Greek literary and rhetorical culture, later termed the Second Sophistic, emerged as a response to Greek efforts to define their role within the Roman world. Philostratus, in his Lives of the Sophists, identified this movement as one focused on performative oratory, with figures like Dio of Prusa and, later, Herodes Atticus at its forefront.

Plutarch, however, stood apart from this tradition. Unlike Dio, who engaged in public discourse and civic debates to shape Greek cities under Roman rule, Plutarch took a quieter, more reflective approach. His Parallel Lives shifted the focus away from contemporary politics, instead drawing lessons from the great figures of Greek and Roman history.

Dio’s oratory was dynamic, confrontational, and self-referential, while Plutarch’s tone was measured, aiming to counsel rather than command. He subtly wove his personal connections with prominent Romans into his works, dedicating treatises to them and portraying a blended society of Greeks and philhellenic Romans, as seen in his Table Talk.

While Dio used his speeches to assert influence in his home city of Prusa, Plutarch remained primarily a philosopher, not a statesman. His preferred form of expression was the essay, dialogue, or biography, rather than the grand oration.

Despite this, Plutarch was one of the most articulate political thinkers of his time. His ethical essays, such as Talkativeness and Curiosity, addressed social ambitions within the elite, while his Advice for Politicians was explicitly written for a young aristocrat aiming to build his career.

However, his most influential work was the Parallel Lives, which examined the political and moral legacies of Greece and Rome through biographical comparisons. The pairing of Greek and Roman figures—such as Epaminondas and Scipio, Pelopidas and Marcellus, or Philopoemen and Flamininus—created a framework where their virtues, struggles, and leadership styles could be weighed side by side.

Plutarch’s comparisons suggested no inherent superiority of one culture over the other. His moral outlook, drawn from Platonic and Aristotelian traditions, emphasized self-control, reason, and civic virtue, ideals that he saw as universal rather than exclusively Greek or Roman.

His Parallel Lives assumed a readership that shared this perspective, offering a vision of history where ethical leadership, rather than nationality, defined true greatness. Through his writings, Plutarch provided a bridge between two worlds, proving that the best ideals of Greece and Rome could coexist, shaping the moral and intellectual fabric of the empire.

Plutarch’s Table Talk and the Art of the Symposium

Plutarch begins Table Talk with a lighthearted yet pointed remark:

“I dislike a drinking companion with a good memory”.

He borrows this line from an early poet but then promptly excuses himself for recording the many conversations he and his friends shared over wine. His Table Talk, a collection of nearly a hundred dinner discussions spread across nine books, is not meant to dwell on indiscretions but to celebrate the pleasures of conversation, friendship, and philosophy.

The symposium, for Plutarch, was more than just drinking; it was φιλοποιός, “friend-making”. His work, too, serves this purpose—strengthening bonds with his friend Sosius Senecio and extending this friendship to his readers.

Yet beneath the convivial tone, Plutarch subtly warns of the dangers of wine.

“What is said over wine is often better forgotten,”

…he implies, recalling the violent feasts of Greek mythology, from the drunken rampage of the Centaurs to Alexander the Great’s fateful murder of Cleitus. A symposium could foster friendship, but it could also dissolve into παροινία (rowdy drunkenness). To ensure harmony, wine must be blended with intellect, Dionysus must be tempered by the Muses. In his Symposiaca, Plutarch repeatedly emphasizes the necessity of balance—ἐμμέλεια (harmony) and κρᾶσις (proper blending).

In Table Talk, Plutarch positions himself as the ideal συμποσίαρχος (symposium leader), guiding his guests not by restricting their wine but by directing their conversation. His role, he suggests, is akin to a musician tuning a lyre—

“to tighten up on wine with one and relax on another”

—ensuring a symphony of personalities rather than a cacophony of excess. Discussions should be a blend of σπουδή (seriousness) and γελοῖον (playfulness), reinforcing friendship rather than fueling hostility.

Plutarch’s dialogues are not nostalgic indulgences but serve a deeper purpose. Roman feasts, unlike the Greek symposia, were often marked by excess—Sulla reveling with actors, Antony’s legendary debauchery, even the Stoic Cato needing to be carried home. Plutarch avoids direct moralizing but instead presents an ideal, offering Table Talk as a subtle corrective to an age of indulgence.

“Dionysus must hide among the Muses,”

…he writes, implying that wine, when tempered by intellect, fosters friendship rather than folly.

Ultimately, Table Talk is not merely a collection of past conversations but a guide to the art of refined social interaction. Addressing his distant friend Senecio, Plutarch wistfully quotes Homer:

“For between us lie / full many a shadowy mountain and sounding sea.”

The symposium, like Table Talk itself, bridges this divide—offering warmth, wit, and wisdom across time and space. (Plutarch and his Roman readers, by Philip A. Stadter)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: