Nero Unmasked: The Fire, the Fame, and the Fury of Rome’s Most Infamous Ruler (Part 2)

Through myth, theatre, and fire, Nero transformed scandal into legend. Reviled by elites yet adored by crowds, he turned empire into stagecraft and himself into Rome’s most enduring paradox.

History remembers Nero as both emperor and spectacle—the ruler who blurred the line between power and performance. His life played out like a tragedy written by his own hand: myth turned into policy, theater into rule. From the burning of Rome to the final hours of his flight, he shaped every scene to control his image, even as that image devoured him. The Second Part of his story follows the emperor’s descent from divine actor to doomed fugitive, tracing the collapse of a dynasty and the rise of a legend that refused to die.

The Myth and Theatre of Nero

Nero’s life has come down to us as a catalogue of excess and atrocity. Emperor of Rome from 54 to 68 CE, he is remembered for murdering his mother, “fiddling while Rome burned,” and for an endless sequence of crimes that blur into myth. He killed or ordered the deaths of most of his family: a mother strangled, a pregnant wife kicked to death, stepsisters executed, a stepbrother murdered.

He married two freedmen—one after castrating him—and raped a Vestal Virgin. He melted the sacred household gods of Rome for profit, and after the Great Fire of 64 CE, erected his glittering palace, the Domus Aurea, over the ashes of the city.

He blamed the fire on Christians, lighting them as human torches in his gardens. He sang, raced, and acted across the empire, winning every contest he entered—even when he fell from his chariot. By thirty, despised by the elite, abandoned by the army, and pursued by rebellion, Nero took his own life, sealing his place among history’s monsters.

And yet, even monsters can be beloved. The same emperor who horrified senators and Christians inspired loyalty among the people. Those who controlled the written record—the elite and the early Church—shaped Nero’s reputation. To senators, he became the archetype of tyranny, a warning against the corruption of power; to Christians, he was the Beast of Revelation, the Antichrist himself.

Yet another, stranger legend spread in the East: that Nero had not died at all, but escaped to await his return.

Bust of Nero at the Capitoline Museum, Rome, restored in the 17th century. Credits: cjh1452000, CC BY-SA 3.0

In these tales, he was not the destroyer of Rome, but its redeemer, the hero who would one day reappear to avenge his people. Centuries later, even Augustine remarked on the enduring belief that Nero still lived. In Jewish tradition, some imagined him converting to righteousness, while Christian rumor painted him as one who listened to Christ himself.

Three impostors claiming to be Nero would arise in later years, one almost sparking war with Parthia. His death, it seemed, did not kill his myth. As one ancient observer put it, “Everyone wants him to come back.” Outside court circles, Nero was a paradox—reviled by elites, adored by crowds. He was, quite literally, a popular monster.

The two crimes that define him—the murder of his mother and the burning of Rome—stand at the center of this mythology. The first is certain; the second, possible. He may well have started the Great Fire.

But within the hostility of our surviving sources lies a question: did Nero’s own people see him as monstrous? Or did they applaud what others condemned? His power rested not merely on brutality but on performance—on an understanding of myth and spectacle that transcended politics.

The Emperor as Actor and God

Two great forces shaped Roman public life and reveal much about Nero’s world: the power of myth and the theatricality of rule. Myths of gods and heroes were the shared language of empire, recognizable to all, from coins and statues to plays and epic poetry.

Great men cast themselves in the image of legendary figures—Pompey as Hercules, Antony as Dionysus, Augustus as Apollo, bringer of peace and the new Golden Age. Politics became theatre; theatre became politics. The masses, anonymous within the circus or amphitheater, learned to read their rulers through these performances. The stage was a mirror of power, and the ruler its central actor.

Nero took this fusion further than anyone before him. After the death of his mother in 59 CE, he abandoned imperial dignity and openly embraced the role of performer. As Cassius Dio recounts, Nero appeared:

“in the guise of a runaway slave, a blind man, a madman, even a pregnant woman in labor,”

his favorite roles being Oedipus, Thyestes, Heracles, Alcmaeon, and Orestes. The masks he wore were sometimes molded on his own face, sometimes on that of his dead wife, Poppaea Sabina. In blurring art and reality, Nero invited his people to see him both as actor and god.

The crowd, Dio notes, “witnessed, endured, and approved,” as did the soldiers. To Roman eyes, steeped in myth and accustomed to symbolism, Nero’s self-identification with tragic heroes could not have been accidental. When he performed as Orestes or Oedipus, he was rewriting his crimes as mythic destiny.

The murder of Agrippina, his mother, was real enough. Tacitus describes it with cinematic precision: the calm night on the Bay of Naples, the treacherous ship, Agrippina swimming for her life, and finally her killers striking her down at her command—“Strike my belly.” Afterward, Nero claimed self-defense, alleging that Agrippina had plotted against him and sought to rule in his stead. He neither denied the crime nor hid it. Instead, he transformed it into theater.

By taking the stage as Orestes, the son fated to slay his mother, he cast himself as the hero of justice, not the villain of impiety. Orestes had avenged his father’s death and freed his city from a woman’s tyranny. Nero’s propaganda echoed the same theme: Agrippina had overstepped the bounds of motherhood, sought imperial power, and paid the price. His guilt became divinely ordained necessity.

Nero’s self-mythologizing extended beyond Orestes. He also performed as Alcmaeon, another tragic matricide haunted by the Furies, and as Oedipus—the son who unwittingly married his mother. The Romans whispered that Agrippina had offered herself to her son to maintain power, and that he had not resisted. Whether true or not, the rumors fed the symbolism. To “conquer one’s mother,” in ancient dream lore, was to conquer one’s homeland.

Julius Caesar himself had dreamt of lying with his mother on the eve of crossing the Rubicon. Nero’s stage Oedipus thus became more than incest—it was a metaphor for dominion, for seizing the world-mother, Rome, and ruling it absolutely. By invoking both Orestes and Oedipus, Nero merged vengeance, desire, and sovereignty into one mythic identity: the son who must sin to rule.

This theatrical rewriting of history also shaped the story of Poppaea Sabina, the wife he was said to have killed in a fit of rage. Tradition holds that he struck her fatally while she was pregnant, then embalmed her body with perfumes, buried her in Augustus’ mausoleum, and declared her a goddess. He later took a boy who resembled her, castrated and married him, calling him Sabina.

When he performed female roles, he wore masks molded on her face. Among these was Canace, the incestuous daughter of Aeolus who kills herself after childbirth. In that role Nero sang of:

“a mother and her baby killed at the same time, and sharing the same grave.”

The audience, hearing the lament through a mask of Poppaea, could not miss the resonance.

Other roles deepened the myth: Heracles driven mad, slaying his wife and children, then awakening in chains to the horror of his deeds. Nero performed this scene “bound by chains of gold,” turning divine madness into absolution. His cruelty became a kind of tragic necessity, his crimes the burden of a hero tormented by the gods.

The echoes ran deeper still. His life imitated Periander of Corinth, the legendary Greek tyrant who had slept with his mother, killed his pregnant wife with a kick, mourned her extravagantly, and sought to cut a canal through the Isthmus—a project Nero himself revived a century later.

The pattern was unmistakable: myth became image, and image became history. The man behind the mask may not have lived the tales told of him, but he used them brilliantly to recast his reign. Through the language of theater and myth, Nero transformed scandal into story, crime into symbol, and himself into legend.

Fire, Sun, and the Golden House

When the Great Fire erupted on the night of July 18–19, 64 CE, the city burned for nine days, destroying most of its regions. Nero returned from Antium and took command of relief, opening gardens to refugees and initiating reconstruction under a stricter building code.

He organized offerings to appease the gods and sought a cause for divine anger. Soon, accusations fell upon a new and suspicious sect—a people “hated for their abominations” who foretold the world’s fiery end. Thus began another chapter in Nero’s legend: the persecution of the Christians, and the birth of one of history’s darkest myths.

Rumor undercut relief. Whispers spread that agents had set the blaze so the city could rise as “Neropolis,” with soldiers preventing bucket lines or even feeding the flames. While families still camped in makeshift shelters, building began on the vast palace at the city’s heart—the Golden House.

Another tale insisted that as Rome burned the emperor stepped onto a palace stage—perhaps even the roof for the best view—dressed as a lyre-player, and, enchanted by the spectacle, sang of Troy’s destruction. (The “fiddle” detail belongs to a much later English fancy, and misleads: the crucial motif is Troy. Once again Roman history begins in Greek myth.)

Whether he ordered the fire remains argued, but he exploited the aftermath. Christians took the blame. In the short term, a forceful action against an unpopular sect likely seemed prudent. One famous non-Christian account lays out who they were—“a most mischievous superstition”—and how punishment fell.

“Mockeries were added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as nightly illumination, when daylight expired.

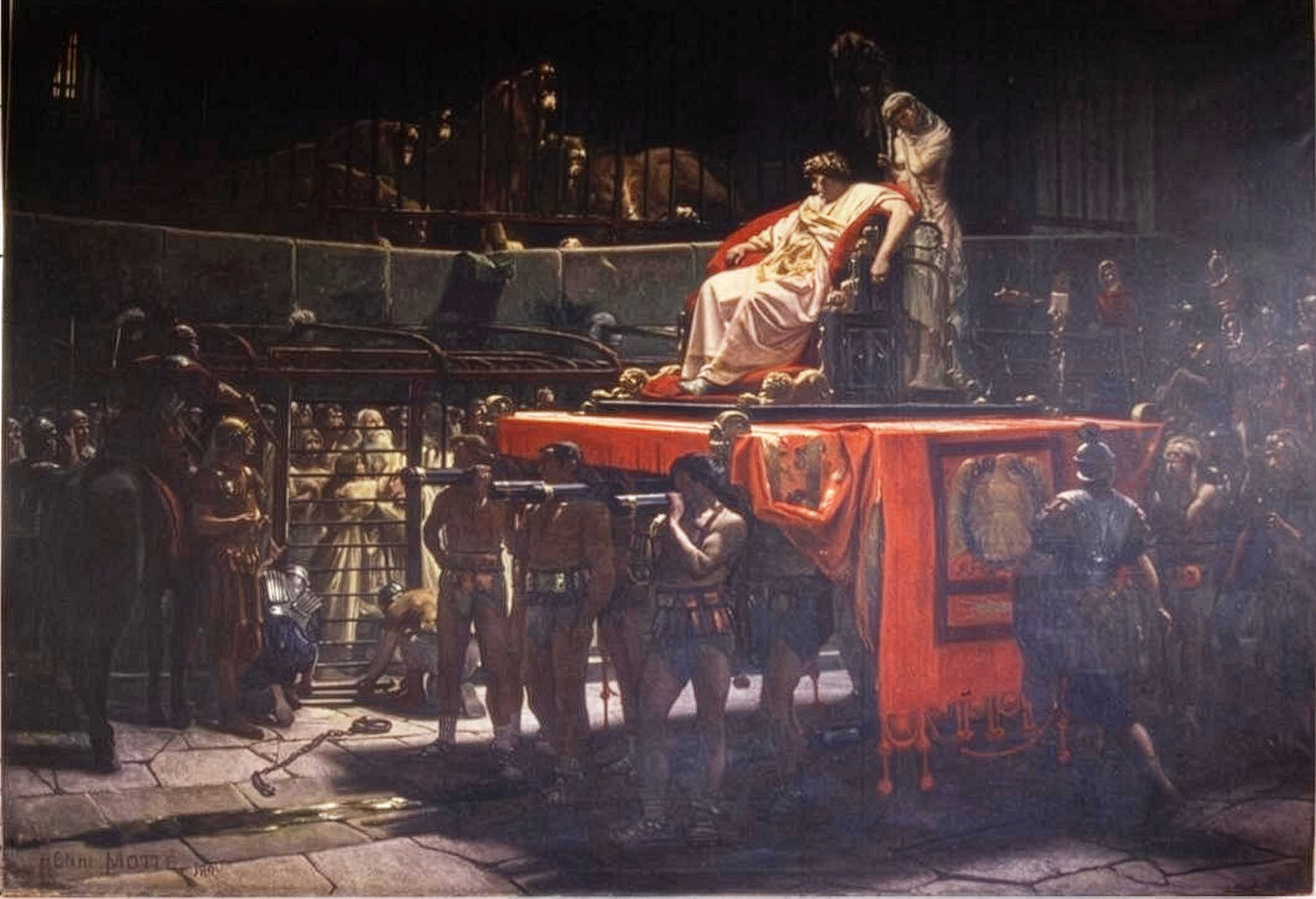

Nero had offered his gardens for the spectacle, and he put on a show in the circus [there], while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood in a racing chariot.”

Public execution at Rome was always theatre, and in this age it became spectacle. Three penalties—beasts, crucifixion, burning—matched charges of arson and impiety; but the “mockeries” show something more: fatal charades, mythic scenes crudely reenacted so that punishment itself became allegory.

So women appeared as Dirce, a wicked stepmother torn by a bull; others as the Danaids, brides who slew their husbands. Connoisseurs caught the rebus: Dirce’s bull pointed to the amphitheater of Statilius Taurus; the Danaids evoked Apollo’s portico on the Palatine.

Dogs worrying “human beasts” nodded to Diana and the doom of Actaeon; human torches gestured toward the Temple of Luna, “Light of the Night,” its eternal flame now replaced by burning bodies so that the night blazed again. To modern eyes this is grotesque; to Roman audiences, it was a legible code.

Myths were messages, staged in blood. Presiding as master of ceremonies, the emperor moved among the crowd on foot or in a chariot, dressed like a charioteer.

From 64, a new image rose from the ashes: the Sun King. He became Sol, Helios—radiant, all-seeing, life-giving—and proclaimed a new Golden Age. Coins show the radiate diadem; inscriptions hail “the new Helios, lighting the Greeks”; even images of the Sun grow chubby, suspiciously like the imperial face.

The supreme statement was the Colossus before the Golden House, towering 120 feet, the emperor as Sol with a spiked crown, the right hand (so it was said) gripping a whip, the left a globe. The very epithet “colossus” would lend its name to the nearby amphitheater in later days.

Sol’s essence is the chariot: the god drives the horses of the sun, and Rome’s circuses—cosmos in miniature—were his domains. In 64 the emperor raced publicly for the first time. The solar charioteer stepped into the daylight.

The next year “the all-seeing Sun” saved his life: a conspiracy gathered—significantly—at the ancient temple of Sol in the Circus Maximus. An awning over the Theater of Pompey in 66 showed him as the charioteer ringed by stars; in 67 he set his Greek victory crowns around the Sun’s obelisk in the Circus, then raced the course, declaring himself the equal of the god. Why Sol, and why then? Because a new day had dawned.

Gold followed fire. A rumor told of Queen Dido’s treasure found in Africa, heaps of unworked gold—the earth itself burgeoning with purity. Panegyrics praised a world that brought forth metal unmixed. In late May 66 came the Golden Day. The emperor crowned Tiridates in a festival so lavish the people themselves named it for the color. The Theater of Pompey glittered:

“the stage of the theater, the walls, everything portable, were all in some way gilded.”

An awning shielded the crowd; at its center the emperor drove Sol’s chariot. The New Sun protected onlookers from his own blaze.

Earlier that morning, at dawn in the Forum, the king bent the knee. White-clad civilians crowded rooftops; soldiers stood in ranks, armor throwing lightning. The ceremony had been postponed once “because of clouds.” The message was precise: the Golden Day would also be the Day of the Sun. The staging would have pleased even the later monarch who shared the title, the Sun King.

Architecture made the myth permanent. The Golden House—the Palace of the Sun—rose while the embers still smoldered. Less a house than a country villa planted in the city, it commanded a parkland basin of woods, pastures, fields, beasts, pavilions, and an artificial lake—an entire world in miniature.

The palace façade, more than 360 meters long, inlaid with gold and gems, was oriented east-west—the only great public building in Rome aligned so—so that from dawn to dusk the sun washed it in fire. Above its entrance the Colossus stood, Sol-Nero with the world in hand. The intention was overwhelming brightness, a blinding display of cosmic dominion.

Criticism came swiftly—cold grandeur amid suffering, prime land swallowed whole—and posterity magnified the scale in retelling. A graffito sneered that one house was taking over the city; later rulers made a point of “giving back” the ground to public use and taught later readers to imagine the palace as a private playground.

Yet a contrary view holds that the house and its park were essentially open, a royal landscape shared with the people. The boast that “Rome is one house” had been the emperor’s own—he would treat citizens as intimates, laying on banquets across the city, filling theater, circus, and forum with shows, and welcoming crowds into his home. The Sun was to shine on everyone.

The fascination endures. The monstrous crimes stand, and the condemnations of two millennia remain. But the image that survives is not only the product of enemies; it is the artifact of imperial imagination. What compelled ancient critics was less the deed than the staging—the audacity with which a ruler composed his own myth in the familiar language of gods and heroes.

Others before him had practiced this art; many after him—Hadrian to Constantine—would do the same with scarcely a murmur. The deeper one reads the Roman code of virtues, archetypes, and allusions, the richer the exchange between ruler and ruled appears.

Sources themselves concede the awkward truth: he was popular. One report of his death divides reactions—senators delighted, leading equestrians pleased, “respectable” folk satisfied—but sneers that the plebs, the “scum” of circus and theater, slaves and wastrels, were not. In other words, the vast majority mourned. It was this bond with the multitude—the banquet-goers, the spectators, the ones who read the myths on stage—that grated on aristocratic sensibilities.

A modern analogy clarifies the paradox. In folklore, a terror-wielding ruler can remain the “good Tsar,” scourge of traitors, companion of outlaws, mingling incognito with commoners. Impatience, misjudgment, even fatal errors become zeal gone astray; cruelty becomes the strong hand of justice. So too the emperor’s popularity—during life and for centuries after—rested on his manipulation of myth and legend, his talent for turning scandal into symbol and power into performance.

One novelist imagined the voice of those who wanted him back. Statues shattered, names erased, heads replaced—yet none of it killed the longing. The rogue senator in that story puts it plainly: the world felt “bare and colorless” when he died; those on the hill “tried to steal our Nero,” but could not. For a few years, they banished imagination; with “our Nero,” color returned—enthusiasm, extravagance, everything that makes life worth living. (Nero Reconsidered, by Edward Champlin)

The book “The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City,” written by Stephen Dando-Collins, follows two intertwined blazes: the literal inferno that consumed Rome in AD 64, and the political conflagration it ignited—one that ultimately toppled the house of Caesar. Drawing closely on a wide range of classical sources, it traces Nero’s trajectory alongside the key players whose fates the fire reshaped.

The story opens at the very start of AD 64, on New Year’s Day, and unfolds from there. The “Final Curtain” is the last chapter of his book. This book is nonfiction history that reads like a novel.

Nero’s Flight, Death, and the Shadow That Wouldn’t Die

Near midnight, the emperor jolted awake with a sense of dread. Barefoot and still in his sleeping tunic, he slipped out into the villa at the Servilian Gardens and found the place abandoned by his German bodyguards—they had retreated to their barracks inside the Servian Wall and even killed their prefect. He sent for friends lodged nearby; only a few came.

Doors he knocked on remained barred and silent. Returning to his room, he discovered that the caretakers had already pilfered his linens and the golden casket that held Locusta’s poison—now more precious to him than the box itself.

He called for Spiculus the gladiator or any executioner to end his life. No one came. Spiculus had been cut down in the Forum by a mob that, since the Senate and Guard had declared for Galba, roamed the streets smashing the emperor’s statues and hunting his allies.

“What? Have I neither friends nor enemies left?”

he cried, running toward the river before his few companions restrained him.

“All I want is a secluded spot where I can hide and collect myself.”

A freedman offered a refuge at his villa, four miles out along the Nomentan-Salarian wedge. The route meant passing the city and the Praetorian barracks, but there was no choice. Five horses were found. He belted on two daggers, drew a faded cloak around him, pulled on a farmer’s hat, and held a handkerchief to his mouth to feign illness.

With him rode the freedman host, his petitions secretary, the eunuch Sporus, and a servant. They likely crossed the Tiber by the bridge that bore his name and threaded the busy streets of the Campus Martius. The warm night shivered with a mild tremor; lightning stitched the sky.

Beyond the Nomentan Gate, voices drifted from the barracks wall—guards speaking of what Galba would do once he had his man. Search parties had already turned over the Golden House and arrived too late at the Servilian Gardens.

“Those people are in pursuit of the emperor,”

a farmer muttered as carts creaked toward Rome.

“What news of Nero in town?”

called another.

They did not answer. A roadside corpse startled his horse; he dropped the handkerchief to steady the reins, and a passing farmer—once a Praetorian—caught sight of the rider. “Hail, Caesar!” the veteran blurted, snapping to attention. The cloth went back up; the little group pressed on.

They turned down a back lane to the villa, dismounted, and picked their way through brush and briars along a reedy pond. Still barefoot, he had cloaks laid as stepping stones over the thorns. Told to hide in a gravel pit, he refused:

“No, I refuse to go underground before I die.”

While others dug through the rear wall, he scooped a sip from the pond.

“This is Nero’s special brew,”

he joked. Inside at last, he sank onto a couch. Coarse bread was offered and declined; a cup of water he took gratefully.

“I was still thirsty.”

The host slipped back to the city to learn what he could. Time stalled. At length his companions urged him to avoid the “degrading fate” that awaited. He wept, told them to dig a grave and gather wood for a pyre, then murmured to himself:

“Dead? And so great an artist!”

Before dawn a messenger arrived with word: the Senate had declared him hostis and ordered he be taken alive for punishment “in ancient style.” Uncertain what that meant, he asked. The answer chilled the room: stripped naked, head thrust into a fork, flogged to death with rods. He tested each dagger point on his finger and dropped them.

“The fatal hour has not yet come.”

He begged Sporus to mourn him and pressed the others to set an example by dying first. None would.

“This certainly is no credit to Nero, no credit at all,”

he muttered, pacing. “

Come, pull yourself together!”

Hoofbeats rattled the front road—Praetorian cavalry. Whether tipped off by the host, the followed runner, or the veteran’s greeting, they were almost at the door. He seized a dagger.

“Help me, Epaphroditus,”

he pleaded. He raised the blade to his throat with both hands; his secretary steadied his grip.

“Don’t let them take my head.”

On his signal they drove the steel home.

A centurion burst in moments later. Blood poured from the torn throat as the officer knelt and pressed his cloak to the wound.

“Too late!”

the dying man gasped, eyes bulging.

“Is this your duty?”

Was the duty to save him only to consign him to the fork and rods?

He was thirty. A rider sped to the city with the news. Some insisted the truth was never fully known. Others told how a freedman of the new ruler refused to allow the head to be taken for display; he said he had seen the body himself and urged a swift cremation intact. The ashes, borne in white porphyry, were laid in the family tomb on the Pincian by a faithful mistress and the nurses of his childhood. For years, flowers appeared there each spring and summer. Statues surfaced on the Rostra; edicts circulated in his name, as though he still lived.

The belief that he would return—Nero redivivus—endured into the fifth century: he had not died, or he would rise, gather armies in the East, and come back to avenge himself.

“Even now everyone wishes he were still alive, and the great majority do believe that he still is,”

one voice of the time observed. In the decades that followed, pretenders with a lyre and a familiar face appeared three times in the East; one nearly drew Parthia into war before being surrendered, the name itself too intoxicating to resist.

In the purge that followed, loyal freedmen died; others, paradoxically, were protected or later restored. Some who had stood with him were executed not for crimes but for influence. One petitions secretary survived and served for years, only to be struck down in a later reign.

The fascination persisted. Writers compiled the fates of those banished or killed under him, and audiences devoured the volumes. Part of the grip lay in the sense of an ending: with his death, the line of the Caesars was broken. He left no heirs. The name would be used, but the dynasty was gone. In that vacuum, rumor paid, and invention flourished; without descendants to defend him, his story became fair game:

- Monstrous? The murders of his mother and adoptive brother stain the record; some would argue the mother’s vaulting ambition as mitigation, and others would lay Octavia’s death at a rival’s feet. Executions of conspirators are cruelty to some, law to others—everything about the age was cruel.

- Tyranny? The picture is not simple: an emperor who forbade death in the arena, tolerated lampoons, endured years of insult from a senator-philosopher, and often kicked decisions back to the House.

- Visionary? Ambitious engineering, once mocked as fantasy, later completed on the same lines; building codes and incentives that made a safer, more ordered city; prosperity before the fire; tax relief that undercut the charge of reckless spending. The burden of rebuilding and the palace that rose with it strained the provinces and fueled anger in Gaul, while misrule in Judea lit rebellion—encouraging a governor in the West to gamble.

In truth, his undoing was forged at Rome. Aristocrats scorned the artist on the throne, the provincials and freedmen in office, the pageant of power performed in public. The plot that followed the fire showed how many of rank and sword were ready to try another Ides. Even failure planted a seed. Whispers about oracles and omens spread; a rumor machine turned and turned again.

Ambitious men moved. A prefect unseated a rival, bought the Guard, and, perhaps from the night of the first flames, tugged at strings in the dark. The end came quickly: one ruler to the next, a year of chaos, until a soldier-emperor from a new house stabilized the state—and honored, oddly, the memory of the fallen performer.

Had there been no fire, the story might have bent another way. Campaigns to Ethiopia and the Caspian could have remade him as conqueror, with years to reign and sons to continue the line. Instead, the blaze of July 19 set the course: the dynasty ended, and with it an era. The world that followed was born from that night’s flames.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: