Inside Roman Society: How Ordinary Life Shaped an Extraordinary Empire (Part 2)

Chains, poverty, bread, and spectacle — everyday realities shaped Roman life as much as empire and conquest. From slaves in collars to crowds in the arena, ancient voices reveal a society built on labor, patronage, and performance, where survival and glory intertwined.

Slavery was a cornerstone of Roman society, present in households, agriculture, industry, and the imperial administration. Estimates suggest that in Italy slaves may have made up as much as a third of the population. Their presence was so common that Romans sometimes described them as “living tools.”

Chains, Collars, and Freedom: Slavery in Roman Society

Columella, writing on agriculture, recommended the ergastulum, a barracks-prison for farm slaves, and emphasized saving costs on heating:

“It is better to have one kitchen and to keep them warm from that, than to set up separate hearths for each”

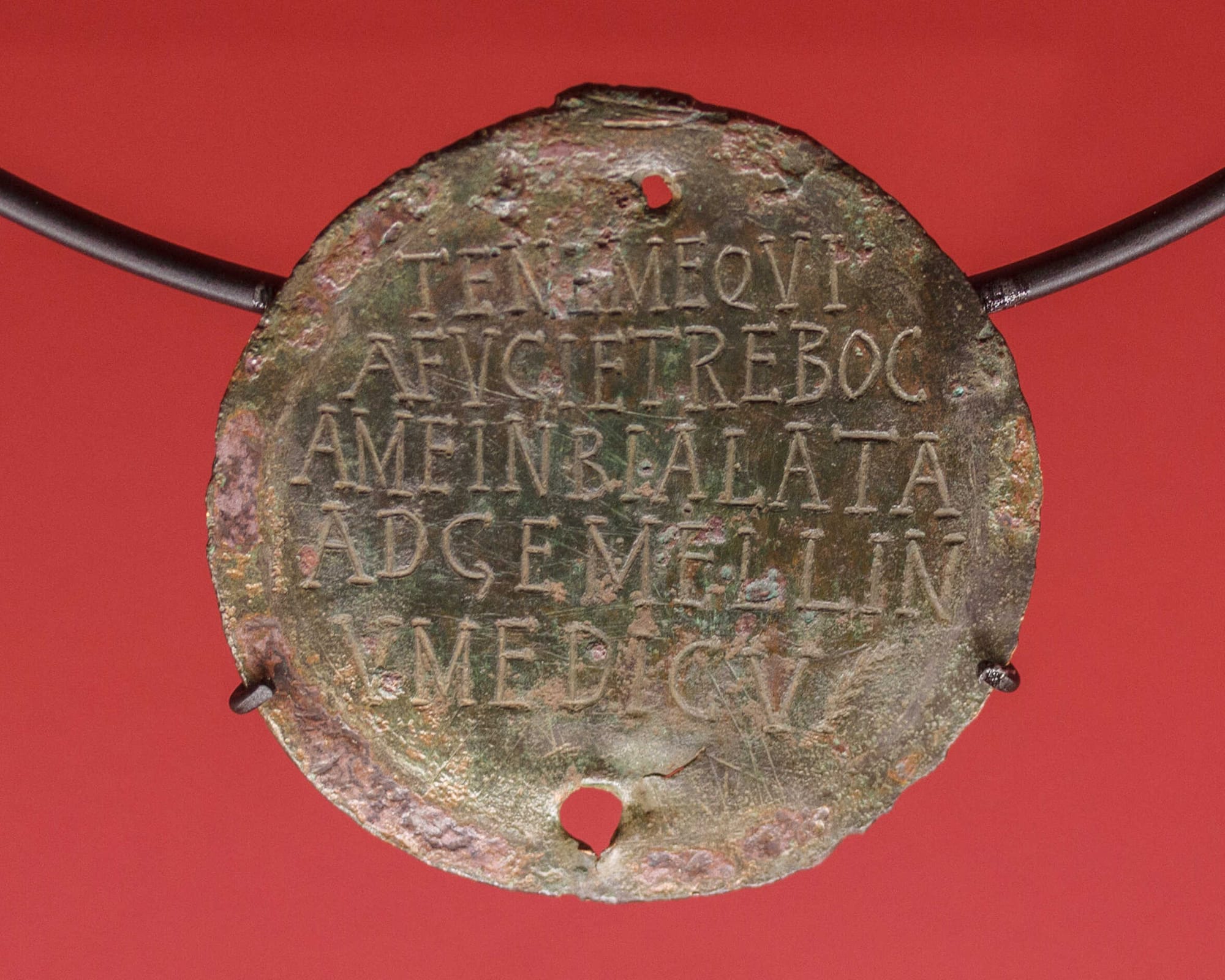

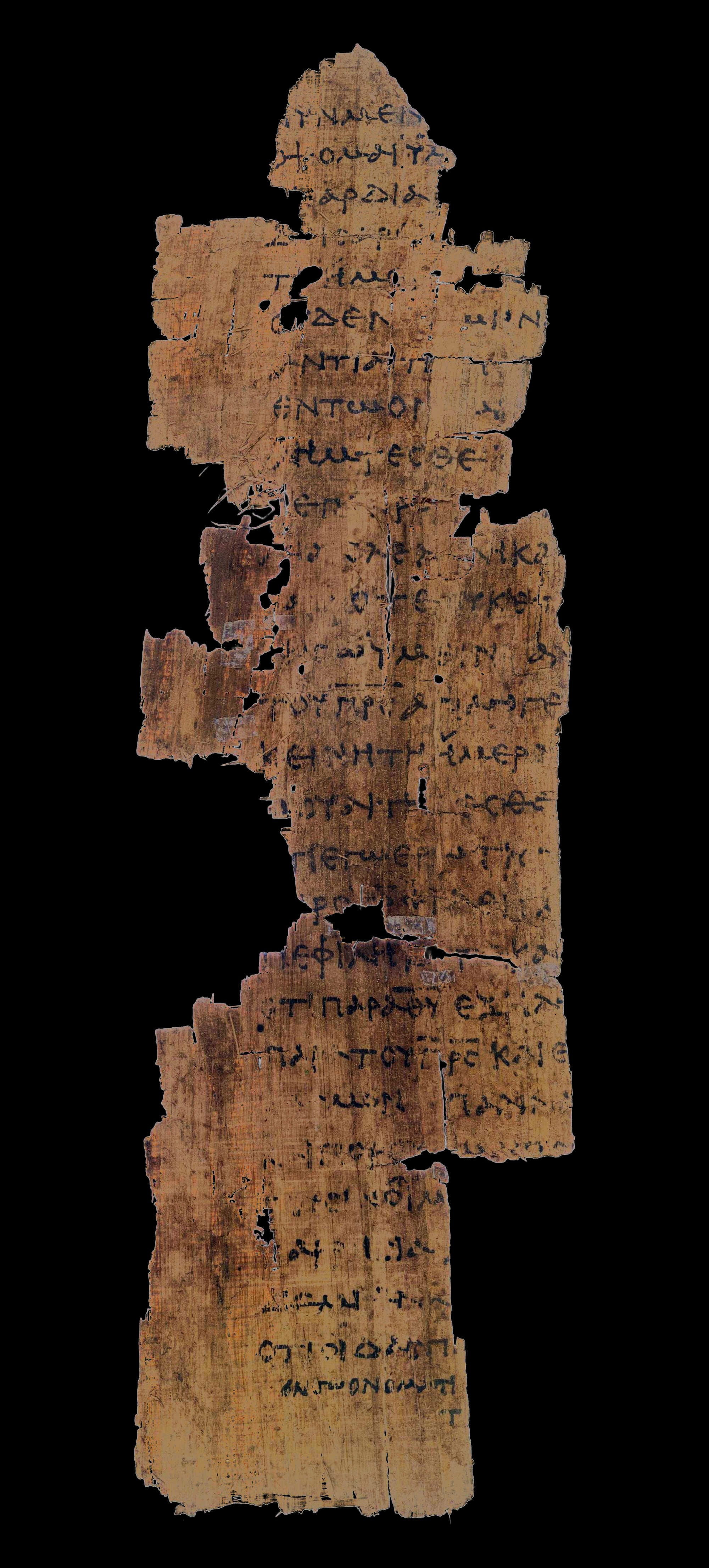

Runaways were a constant problem. Papyrus notices from Oxyrhynchus mock fugitives in humiliating detail, such as one describing a thin, bald-headed weaver with a high-pitched voice, urging capture and reward. Recaptured fugitives might wear collars inscribed:

“I have run away. Seize me. When you return me to my master Zoninus, you will receive a reward.”

Fear of revolt bred severity. Tacitus described the collective punishment after the prefect Pedanius Secundus was murdered in 61 CE:

“When a slave murdered the city prefect … four hundred slaves, men and women alike, who lived under the same roof, were all executed”

The senatus consultum Silanianum reinforced such measures, requiring household slaves to be interrogated or executed if their master was killed. Roman law also allowed slaves limited hope through the peculium, personal savings that might one day buy freedom. Ulpian admitted the fiction:

“A slave cannot have money of his own; but, with a nod and a wink, it is believed that he was bought with his own money”

Digest

Manumission was common, producing freedmen who retained obligations to former masters. Gaius explained their categories:

“Those who are manumitted become either Roman citizens, or Latins, or in the class of ‘surrendered foreigners’”

Some slaves rose to prominence in elite households. Tiro, Cicero’s freedman, not only managed his master’s affairs but preserved his writings for posterity. Suetonius recounts similar cases, such as Remmius Palaemon, a former slave who became a wealthy and famous grammarian.

Slavery in Rome thus encompassed extremes: forced labor in mines and ergastula, collars branding runaways, but also opportunities for education, wealth, and eventual freedom. It was an institution of both terror and mobility, essential to Rome’s economy and its daily life.

The Many Faces of Poverty in Rome

Roman society was starkly divided between rich and poor, though “poverty” could mean very different things. It stretched from artisans and vendors (pauperes) to the utterly destitute (egeni), mocked by Martial as too poor even to be considered poor:

“You have no cloak, nor hearth, nor a bed chewed by bed-bugs … Still, Nestor, you make a pretence of being called and appearing to be a poor man … That’s not the definition of being poor: ‘having nothing at all’”

Philosophers often praised poverty as freedom from the corruption of wealth. Dio Chrysostom argued that rural poverty could be honorable:

“Poverty isn’t a problem but provides a livelihood and a lifestyle that befits free men who want to live independently … more natural than those in which wealth usually encourages most people to engage”

Yet urban poverty was harsher: underemployment, despised manual work, and prostitution sustained countless lives. Dream interpreters even saw fate differently for rich and poor. Artemidorus explained that lightning in a dream meant ruin for the wealthy but fame for the poor:

“The poor are like bare and humble places, where dung is thrown … lightning makes ignoble places renowned … so the dream is of advantage to the poor, but hurts the rich”

Support came not from state welfare but from networks of family and patrons. Trajan’s alimenta scheme and the grain dole at Rome selected beneficiaries by “worth” rather than need. Occasional windfalls came from sacrifices or funerary banquets, while beggars scoured markets, graveyards, and crossroads. John Chrysostom later condemned the rich who ignored the needy while feeding flatterers and informers:

“You, who have your bellies full and are well fattened … don’t you deserve to be punished for so criminally using God’s gifts?”

For most Romans, poverty meant insecurity. Some endured it with resignation, some with pride, others with shame or resentment. The poor were ever-present in the streets of Rome and its provinces—a reminder that the empire’s grandeur rested on fragile lives at the bottom of society.

Bread, Wine, and Coin: The Roman Economy

At its heart, the Roman economy was agricultural. Cereals, vines, and olives dominated Italy’s farmland, though Rome depended heavily on imports of grain from Sicily, Africa, and Egypt. Columella lamented that farming had lost its dignity:

“We let contracts so that grain may be carried to us from provinces across the sea … common opinion is now publicly conceived and confirmed that farming is a lowly task”

Large estates (latifundia) existed but were less common than moralists suggested. Pliny the Elder remarked bitterly:

“Latifundia have ruined Italy and are in the process of doing the same to the provinces too – six masters used to own half of Africa, until the emperor Nero executed them”

Most landholdings were small to medium, leased to tenants or worked by slaves, with profits dependent on weather, markets, and social pressures against excessive gain. Transportation shaped commerce. Land carriage was costly, while river and sea routes allowed cheaper grain shipments to the capital.

Pliny the Younger’s letters show how landlords petitioned the Senate to establish markets on their estates, while emperors like Trajan regulated storage and trade to stabilize supply. Beyond farming, mining, manufacturing, and trade connected Rome to the wider Mediterranean and even India. Pliny the Elder calculated the scale of eastern luxury imports:

“By the lowest reckoning, India and China and the Arabian peninsula take from our empire 100 million sesterces every year: that is how much our luxuries and our women cost us”

Strabo confirmed the traffic, noting that:

“120 ships were sailing from Myos Hormos to India, whereas formerly in the time of the Ptolemies very few ships dared such a voyage”

Economic life was always precarious. Grain shortages sparked riots, peasants lived off barley or wild foods in lean years, and emperors intervened to prevent famine. Yet the empire’s scale encouraged investment, specialization, and trade networks that made Rome both vulnerable to crisis and capable of unprecedented consumption.

Justice, Patronage, and Punishment: Law and Courts in Roman Society

Roman law was a unifying but uneven system. Before 212 CE, it applied only to citizens; after the Antonine Constitution extended citizenship, local laws still operated, as seen in Egypt:

“If someone lodges a complaint … that the guttering of the house of the defendant is soaking his house with the run-off water, the judges should examine … If the water soaks the house of the plaintiff, they should cut off enough of the guttering until it no longer soaks the house”

Emperors could intervene directly in civic disputes. Hadrian instructed the people of Aphrodisias in 119 CE:

“If a Greek of Aphrodisian birth … is prosecuted by an Aphrodisian Greek, the trial should take place under your laws at Aphrodisias. If, however, a Greek [who is not an Aphrodisian is prosecuted], the trial should occur under Roman law and in the province”

Letter of Hadrian to Aphrodisias

Patronage was central to legal practice. Dionysius of Halicarnassus explained its origins:

“Patrons were obliged to explain the laws to their clients, to plead their cases in court, and to defend them if they were accused”

Judges considered character as well as evidence. Aulus Gellius recalled a case where the moral standing of the parties shaped perceptions:

“It was agreed that [the plaintiff] was a truly decent man … utterly without reproach … The fellow … was barely solvent, with a disreputable low-class lifestyle … Still he repeatedly demanded … that it ought to be proven … by receipts or witnesses”

Litigation was seen as corrupt or futile. Petronius, in his satirical novel, has Ascyltos reject legal recourse:

“Who knows us here and who will put any trust in our word? I’d really prefer to buy it, even if what we’ve recognised is ours … rather than descend to the uncertainties of law”

Wills and inheritance occupied jurists, while blackmailers (delatores) plagued the system. Class also determined penalties. Constantine decreed:

“If [a kidnapper] is a slave or a freed man, he is to be thrown to the beasts … if he is a free man, however, he is to be put into the gladiatorial games, with this provision, that he should perish by the sword before he can do anything to defend himself”

Philosophers also debated punishment. Aulus Gellius summarized the rationales:

“One reason … is correction … Another reason … is retribution … The third reason … is example, so others through the fear of the punishment … will be deterred”

Prisons were harsh, mainly used before sentencing; debtors were often confined illegally. Apuleius satirized abuses by soldiers requisitioning property (Metamorphoses), while Libanius confirmed that landlords summoned military backing in disputes. Roman justice, then, balanced law, morality, and hierarchy: a system where rights existed, but outcomes often depended on patronage, status, and power.

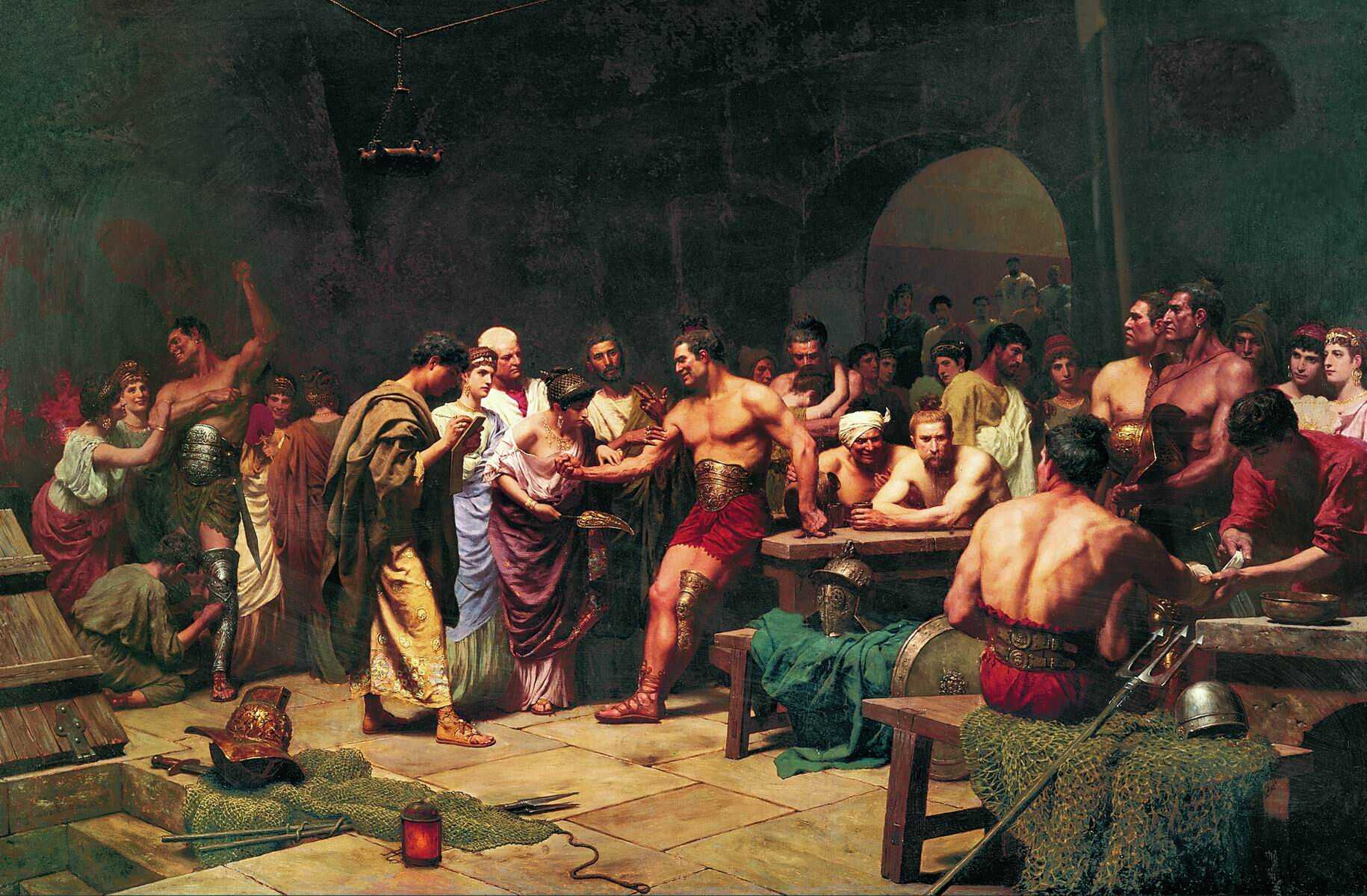

Blood and Spectacle: Leisure and Games in Roman Society

Public entertainments—races, theatre, hunts, executions, and gladiatorial combats—were central to Roman civic and political life. They filled amphitheatres and circuses across the empire, binding communities together in celebration, rivalry, and violence.

Juvenal captured the popular appetite for shows with biting irony:

“The people that once bestowed commands, consulships, legions, and all else, now meddle no more and long eagerly for just two things: bread and circuses”

Fronto explained Trajan’s wisdom in indulging these appetites:

“The Roman people is captivated by two things in particular, the grain supply and the shows”

The games were also political theatre. Cicero admitted their electoral power:

“Murena’s shows helped him considerably. For these displays of gladiators, though they are given to the people, yet win the favour of the populace for those men by whom and in whose name they are given”

For some, the spectacle was crude or empty. Pliny the Younger dismissed the circus:

“I am disgusted at the childish passion of men for an absurdity—if those engaged in the race were only charioteers, or if it were the horses they favoured, there might be some sense in it; but as it is, it is the colour they support … So they are all as interested in a bit of cloth”

Yet in his Panegyric, he praised Trajan’s shows:

“You present them with shows to inspire them to face fine wounds and show scorn for death”

Reactions could be visceral. Augustine recalled how his friend Alypius, dragged unwillingly to the arena, vowed to keep his eyes shut—yet:

“He opened his eyes. At once he was stabbed in his soul, and with a far more deadly wound than that which the gladiator had received in his body … he gazed and shouted and was inflamed, and carried away with him the madness that goads to follow and imitate”

Philosophers and moralists weighed the shows against Roman values. Cicero reflected:

“Gladiatorial shows are apt to seem cruel and inhuman to some, and I tend to agree, as they are now conducted. But in the days when it was criminals who crossed swords, there could be no better schooling against pain and death – at least for the eye; for the ear perhaps there might be many”

Plutarch condemned them as ruinous bribery:

“Those falsely named and falsely attested honours that come from giving theatrical shows, handouts, or gladiatorial games, are like the flatteries of a harlot… So you must try to drive out of the state all those ambitious displays that excite and nourish the murderous and savage or the obscene and debauched” (Precepts of Statecraft 821f–822c). Seneca warned: “…insensitivity and cruelty towards people follow savage spectacles”

Christian voices were harsher still. Tertullian declared:

“The amphitheatre is the temple of all demons. As many unclean spirits reside there as it contains people”

Constantine eventually echoed such views in law:

“Bloody spectacles do not please Us amid civil peace and domestic tranquillity”

The games, then, were never just entertainment. They were instruments of politics, stages of imperial propaganda, schools of virtue and vice, and mirrors of Rome’s moral anxieties. They reveal both the magnificence and the brutality of a society that celebrated itself in blood. (Roman social history. A sourcebook, by Tim G. Parkin and Arhur J. Pomeroy)

Everyday life in Rome was lived between harsh necessity and dazzling display. Slaves bore collars, the poor scraped by, farmers and merchants labored under constant risk, and crowds flocked to spectacles both brutal and sublime. These ordinary rhythms sustained the empire’s extraordinary power.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: