Did Ancient Romans Exercise to Keep Fit?

The idea that exercise and physical activity are beneficial is not a recent discovery; it has been recognized and practiced for thousands of years.

The Romans' fitness philosophy was rooted in earlier traditions, particularly the Greek idea that mental and physical health were interconnected. However, the Romans, being more pragmatic, focused heavily on the physical aspect.

They believed that maintaining one’s body through hygiene and regular exercise was crucial to health, emphasizing prevention as more effective than any cure. Cleanliness and physical activity were seen as the essential foundations for a healthy life, during the Roman era.

The Journey to a Healthy Lifestyle

One of the most influential figures in ancient health and wellness was the second-century A.D. physician and philosopher Galen. He viewed health as more than just the absence of disease, believing it could be achieved by maintaining a balanced lifestyle, with moderate exercise being a key factor.

For the Greeks, physical exercise was closely tied to competition, particularly in events like the Olympics. These contests were reserved for young men of certain social classes, and exercise was also essential for preparing them for military service, excluding women from participation.

In contrast, in Roman society, exercise was embraced more widely, and both men and women were regular participants. Public baths were popular gathering spots for physical activity, where men engaged in activities such as ball games, running, wrestling, boxing, and weightlifting.

Women, on the other hand, often swam, played a hoop-rolling game called trochus, and favored ball games. Galen advocated for ball games as effective exercises for both mental and physical fitness, showing how the Romans saw exercise as a means of enhancing overall well-being.

During the Roman Empire (up to around 500 AD), the health benefits of exercise were widely acknowledged.

Aniello Falcone - Roman Athletes. Credits: Prado, Public domain

Physical fitness was vital for military readiness, but it was also part of a broader approach to health. Fitness and health were viewed as aspects of dietetics, a branch of medicine focused on regulating food, drink, exercise, and bathing. Trainers at Roman baths often gave advice on fitness and diet, while doctors, located in small booths near the bathhouses, prescribed treatments, including bathing, for both maintaining health and curing illnesses.

Roman baths ranged from small private buildings to large public complexes that served as social and fitness centers. These facilities, such as the Baths of Caracalla, featured hot, cold, and warm immersion pools as well as rooms for exercise. Romans had 159 public holidays each year, and much of their leisure time was spent at these baths, engaging in various recreational and therapeutic activities.

Unlike the Greeks, who emphasized athletic competitions, Romans preferred to engage in sports as spectators rather than participants. Athletic festivals similar to the Greek Olympic Games were not popular in Roman society, though they were open to fitness through sport. (A history of physical activity, health and medicine, by Domhnall MacAuley)

Did the Romans Play Football?

The word harpastum is described in both Greek and Latin dictionaries as a type of handball. Literary references identify it both as a ball game and a handball. It's unclear whether the name of the ball came from the game or vice versa, but it is certain that the Greeks had multiple names for it.

Athenaeus, a Greek scholar from the second and third centuries A.D., states that harpastum was originally called phaininda, while Clemens of Alexandria also refers to the game by the same name. Additionally, Eustathius, a 12th-century archbishop of Thessalonica, supports this claim. No ancient sources distinguish these games as separate, and both Athenaeus and Pollux identify them as the same.

Athenaeus, in his writings, expresses a personal fondness for harpastum, noting it was his favorite game, further affirming the connection between the two names. The Etymologicum Magnum, the oldest Greek lexicon from the 10th century, traces the term phaininda to phennis, meaning trickery. This etymology is relevant to the game's play style, which, as described by Julius Pollux (a Greek scholar and rhetorician), involved deceptive maneuvers where players pretended to throw the ball in one direction and then threw it in another.

Athenaeus provides a detailed description of phaininda, explaining how one player seized the ball and passed it to another while avoiding a third, amidst cries of "out-of-bounds" and the game's rough physical movements. Archaeological evidence, though sparse, includes a sculptured relief found in Athens in 1922, depicting six players engaged in a ball game, supporting these literary descriptions.

Some scholars who claim to have reconstructed harpastum base much of their understanding on Galen’s treatise, "The Small Ball." However, Galen is more interested in various exercises through ball games, and there is no conclusive evidence that he refers solely to harpastum. Galen does provide useful clues, mentioning that the exercise involves "the arms in throwing and the legs in running," without mentioning kicking, suggesting the absence of that element.

In such a comprehensive treatise, Galen would likely have noted the leg exercise involved in kicking if it had been part of the game.

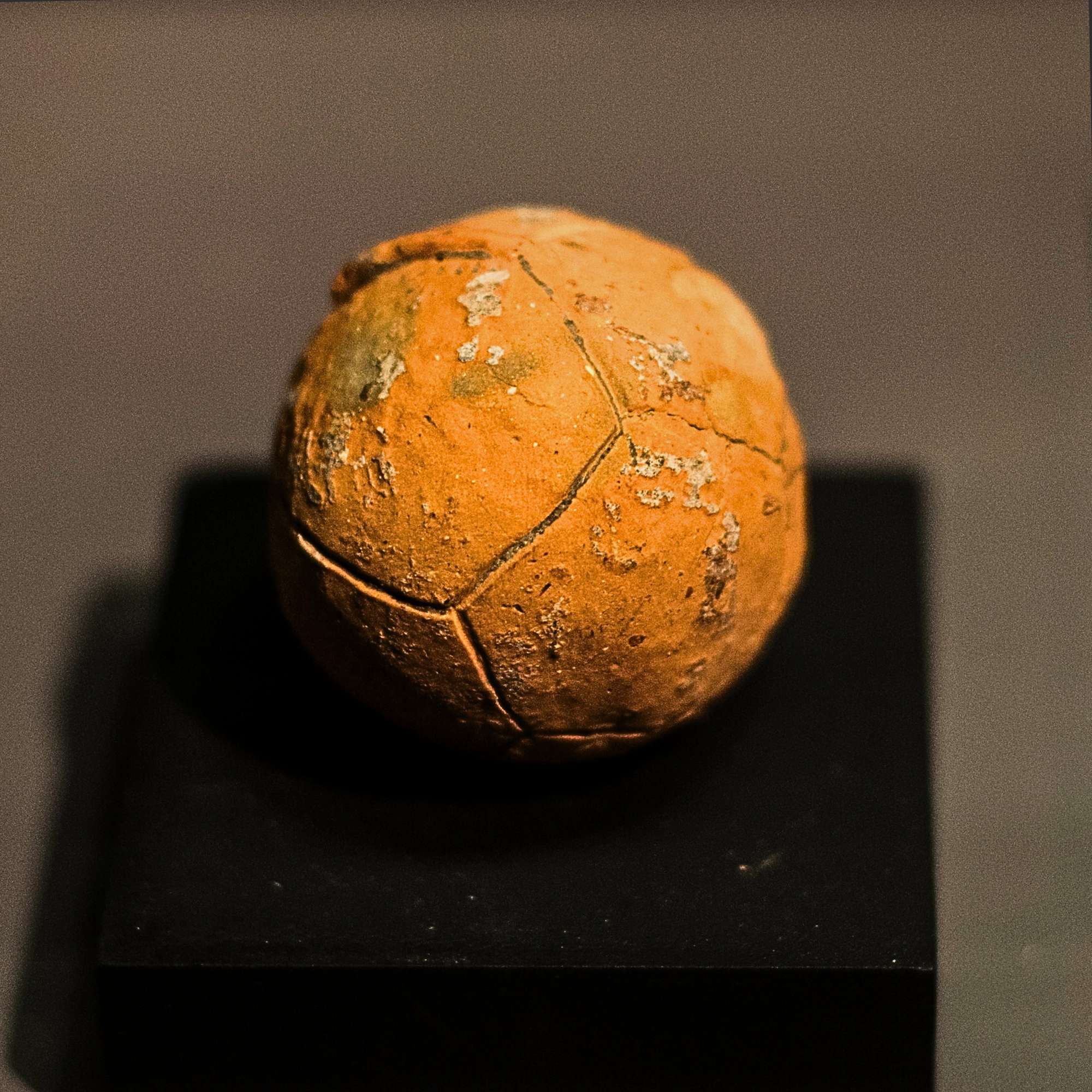

Terracotta miniature in the form of a leather ball, from Samothrace. Credits: diffendale, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The information available on harpastum is limited and can be summarized as follows: it was a game, where two or more players passed the ball while trying to avoid a middle player. Beyond this, most details are speculative. Martial’s use of words like puloerulenta (dusty) and arenaria (sandy) implies that the ball may have hit the ground before being caught, though there is no indication that catching the ball on a rebound earned points. (more information below on Ball Games)

Some believe the players stood in a circle, based on a passage from Isidore, although this text is unclear. Sidonius Apollinaris may describe harpastum when he refers to a middle player (medicurrens) who loses balance and leaves the game breathless, similar to modern "Keep the Ball" games. However, players seemed to enter and exit freely, suggesting harpastum wasn’t a traditional team game.

Some scholars also confuse harpastum with episkyros. While there is no evidence of kicking in episkyros, there are signs that it might have been an early form of soccer. Pollux explains episkyros as a game where teams sent the ball across a middle line, the skyros:

“There was a middle line, the skyros, upon which the ball was placed... This performance continued until one team succeeded in throwing the ball beyond the goal line of the other team.”

There is no conclusive evidence that the Greeks or Romans played football. Perhaps they were not skilled enough to meet a flying ball with their feet, or, as Epictetus said, they struggled to catch the ball even with their hands. (Did the Greeks and the Romans Play Football?, by Norma D. Young, State University of Iowa)

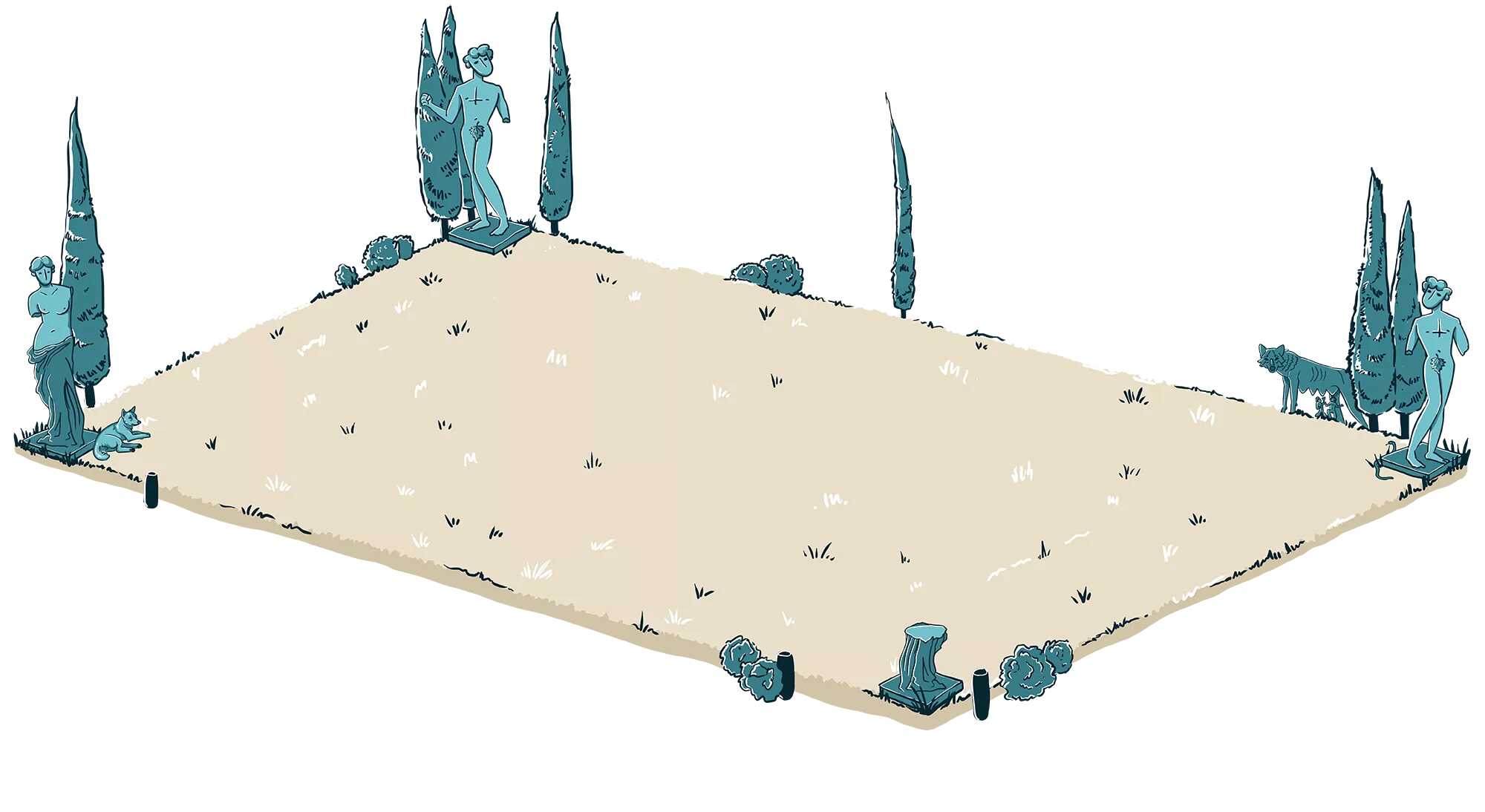

Image #1, The Pitch: No historical accounts provide specifics about the pitch’s size, layout, or location. It remains ambiguous how the playing field for Harpastum was structured.

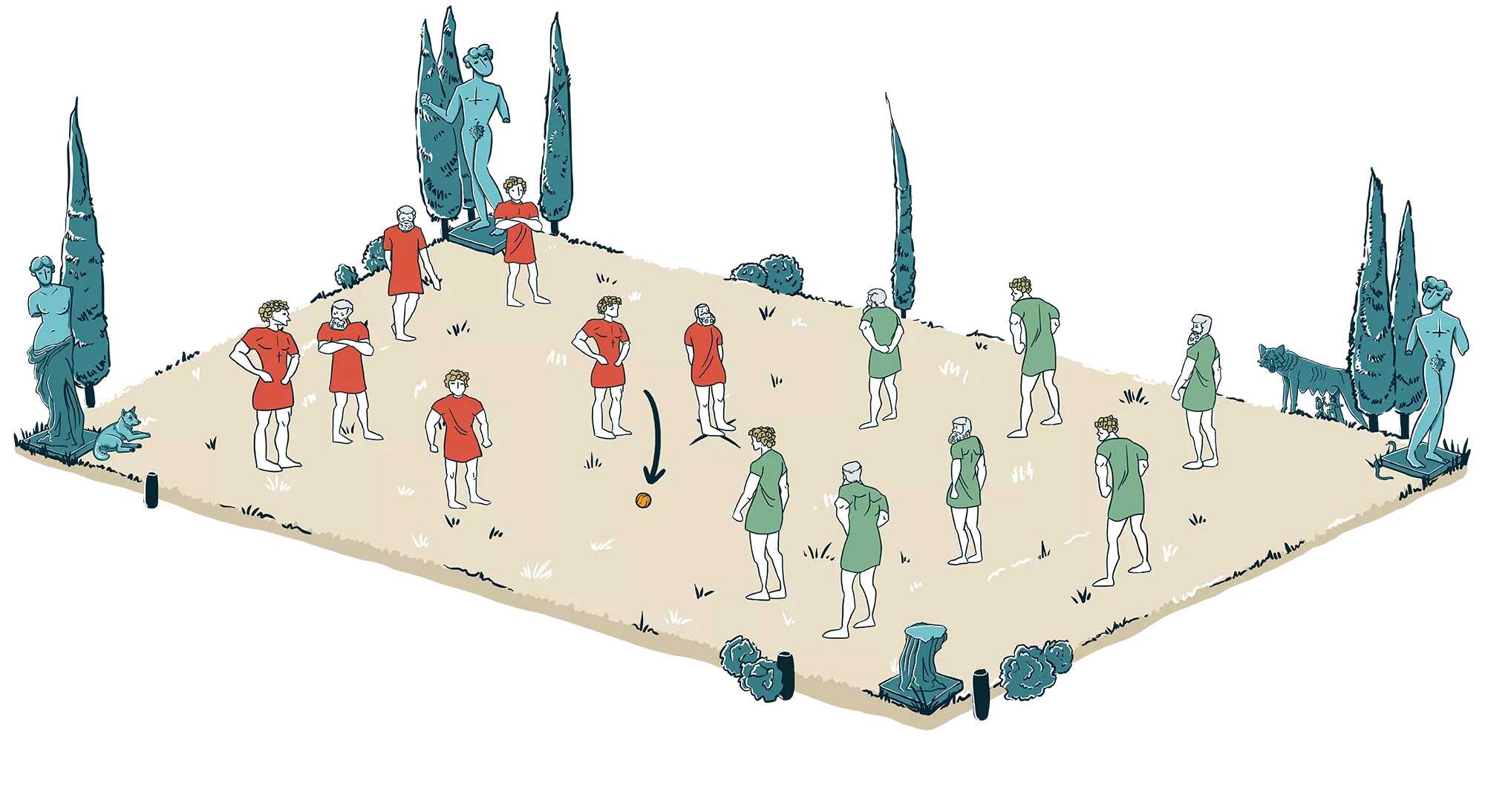

Image #2, The Players and the Ball: Galen of Pergamon described players lining up on opposite sides, trying to prevent a central player from gaining the ball. However, many details, such as the number of players or the game’s start and end conditions, remain unknown. The central player likely belonged to one of the two teams. Pollux described the ball used in Harpastum as “soft,” possibly resembling the feather-stuffed ball from the Greek game Phaininda, where the name comes from the Greek word “arpazo,” meaning “to snatch.”

Image #3, The Gameplay: The most intense form of Harpastum involved participants shouting instructions and launching the ball at or over the central player. The objective was to intercept or avoid the ball, utilizing tackles and wrestling moves. If the ball was intercepted, the roles shifted, with the thrower becoming the person in the middle. Unlike modern sports, Harpastum had no concept of scoring through nets or goals, a feature introduced in Roman ball games much later.

Ancient Roman Ball Games

Martial tells us that there were several types of balls and in consequence, many ways of playing with them. One could play with different types of balls in ancient Rome, including the common pila, which was firm and bounced on the floor. Another option was the follis, a soft, lightweight ball filled with air, described by Martial in his 47th epigram of his 14th book: “A follis is for children and old men to play with."

This ball, unlike the others, was light and soft. In between the pila and follis, in terms of firmness, was the pila paganica or "peasant ball," which was likely filled with farm feathers, as suggested by an inscription found in Africa that mentions a paganicum, probably a room for playing this ball game.

While there aren't many detailed descriptions of the rules for these ball games, Martial offers some insight, particularly about a game called pila trigonalis, which was likely played by three participants in a triangular formation. In one of his epigrams, the ball says:

"If you know how to drive me with swift left-handers, I am yours. You cannot? Then, you rabbit, give up the game."

This suggests that skill with the left hand may have been crucial, perhaps even a requirement for the game. The Romans were aware of the advantages of being left-handed in sports, as seen in gladiatorial contests where left-handedness (scaevae) was often highlighted. Martial also notes this left-hand emphasis in another poem, praising the left-handed technique in pila trigonalis:

“So may the oiled circle’s favoring judgement give you a victor’s palm from the nude trigon, nor praise Polybius’ left-handers more.”

In another humorous epigram, Martial describes a persistent individual named Menogenes, who, even after bathing and dressing, tirelessly participates in ball games, retrieving the follis from the dust to keep playing. This playful imagery reflects the prominence of these ball games in Roman culture.

In addition to trigon, which is frequently referenced in ancient texts, harpastum (mentioned above) is also mentioned, with its origins rooted in Greek, referring to both the ball and the game. Martial notes that, like the follis, it was played on a light, dusty ground. Beyond literary sources like Martial, inscriptions, stucco reliefs, mosaics, and paintings also provide evidence of these games.

For example, stuccoes in the Porta Maggiore ‘basilica’ depict children playing ball, and paintings on a tomb along the via Portuense, dated to the mid-second century AD, show two men and two women, dressed in tunics and long dresses, respectively, trying to catch a small ball. This could be a simple representation of everyday life rather than symbolic of something ritualistic or mythological.

A notable mosaic at the Porta Marina Baths in Ostia, shows sports instruments such as a ring with three strigils, a hoop, and a ball that appears similar to modern footballs, though depicted with hexagonal faces, a likely artistic mistake. The mosaic also features a dodecahedron, reminiscent of Plato's description of the Earth, adding an artistic layer to the representation of athletic equipment.

As for women, they, too, were depicted playing ball, as seen in the Piazza Armerina mosaic, where women in athletic attire engage in various activities like discus throwing, long jumping, racing, and playing ball. These young women may have even been depicted as pentathletes, with the ball game possibly replacing wrestling, which was deemed too rough for females.

Despite Ovid's advice to young women against participating in certain physical activities, including quick ball games (pilae celeres), it's evident that women found suitable forms of exercise, as demonstrated by these mosaics. Interestingly, in some cases, women are shown playing with their left hands, suggesting the significance of left-handedness even in sports like trigon, though the third player of this triangular game may not be shown due to space constraints in the artwork.

Training for the Army

Romans typically engaged in physical activities primarily for military training. Young Romans were introduced to sports as part of their preparation for military service. Vegetius, a fourth-century AD author, discusses the exercises imposed on military recruits, which included running, jumping, and throwing, likening it to a "military obstacle course." Although Vegetius is a later source, he references practices from the Republican era, including the training of Pompey, highlighting that similar exercises were in place earlier.

Additionally, Cato the Elder, in the third century BC, refused to delegate his son's physical training, taking on the role himself. He taught his son essential skills like javelin throwing, armored combat, horseback riding, boxing, enduring extreme temperatures, and swimming in the Tiber River. These activities were central to Roman education, emphasizing practical skills over "Greek" sports like discus throwing, which did not align with Roman sensibilities.

Although military training played a significant role, especially in Rome's early centuries, it wasn't the only reason Romans engaged in physical activities. They also recognized the importance of exercise for relaxation and health, much like people today. Both Aeneid and Ovid's Fasti depict characters from Rome's mythic past, such as Aeneas' companions and Romulus' followers, participating in physical activities like racing, boxing, and wrestling.

However, these depictions might have been inspired by Homer, drawing from The Iliad and The Odyssey rather than reflecting actual early Roman practices.

A representation of Aeneas’ companions training in wrestling. Illustration: Midjourney

Nevertheless, historical records, such as those from the Samnite Wars, reveal the existence of figures like Papirius Cursor, who earned his name from his running speed. During ludus militaris, young Roman soldiers would engage in competitive physical tests, though these were not formal public competitions, setting Roman practices apart from the Greeks, who valued public sporting events. This contrast shapes how we view Roman attitudes towards sports.

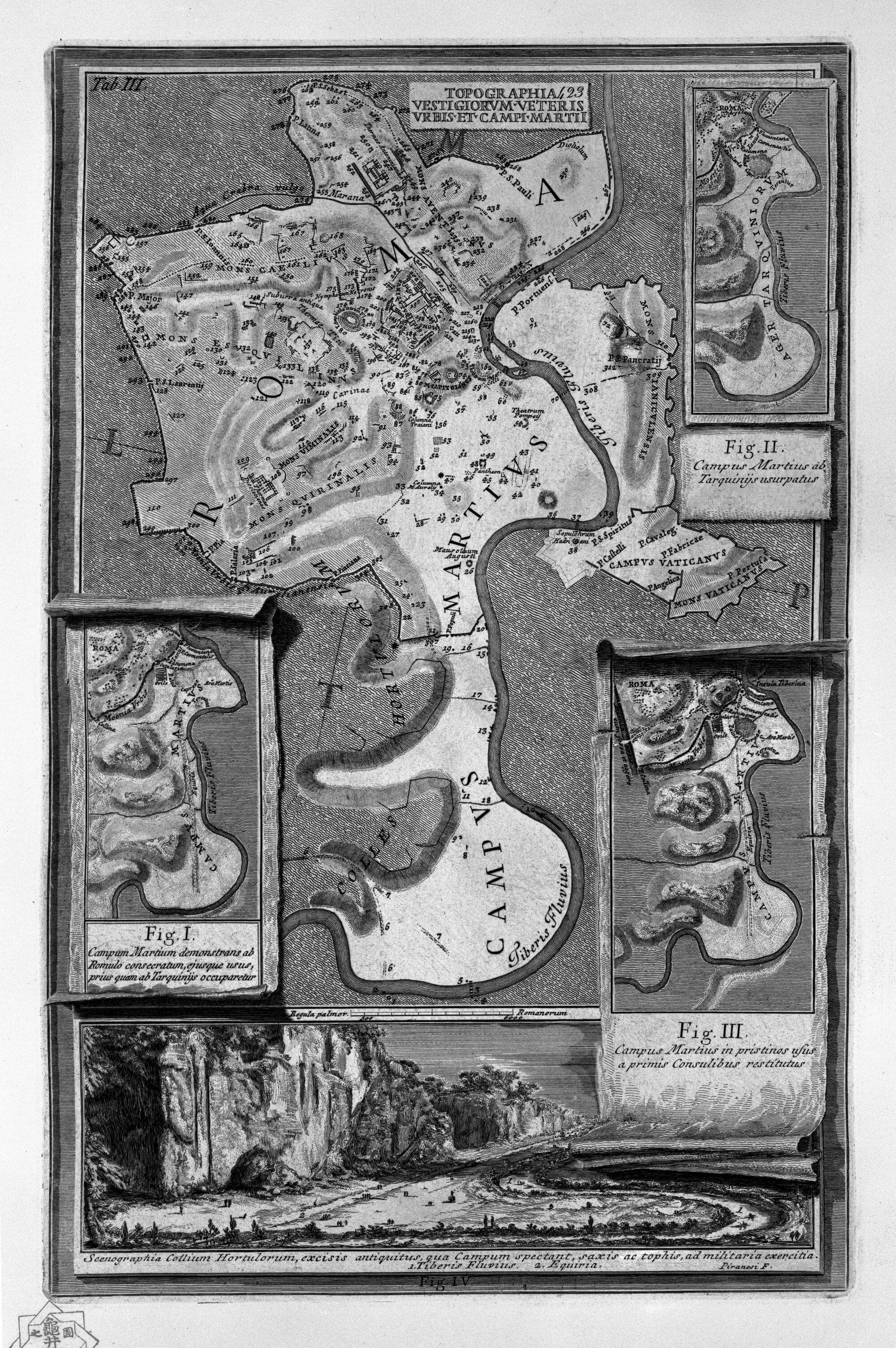

The Campus Martius

At the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Empire, there is the most detailed information available on Roman sporting activities, particularly in the city of Rome. Although the military aspect of exercise diminished over time, the Campus Martius (often just called "the Campus") remained a central location for physical activity.

Both Ovid and Persius referenced this location as synonymous with sport. Vegetius also highlighted the military roots of these exercises, noting that Romans traditionally used the Campus Martius for training, where young men would wash off sweat and dust in the Tiber after practicing with arms, running, and swimming.

Horace, a key literary source, illustrates the dual nature of Roman sport by contrasting the militia Romana, which included hunting and horse riding, with the Greek games like ball playing (pila) and discus throwing. Additionally, hoop-bowling (trochus), a male activity, is frequently depicted in mosaics found in public baths, along with other athletic equipment such as strigils and dumbbells.

Strabo, a Greek geographer, offers a vivid description of the Campus Martius during the Augustan era, mentioning how ball games and hoop rolling were among the favored exercises, alongside horse shows and wrestling, which were part of the ludus campestris. Both Horace and Strabo also emphasize the bustling activity of the Campus, where spectators gathered to either cheer for the strongest athletes or jeer at the weakest. However, these events were informal; Roman citizens did not engage in public, official competitions like the Greeks.

The Campus Martius was the largest and most frequented location for exercise in Rome, but it wasn't the only place dedicated to physical activity. There was a “Little Campus” near the Campus Martius, possibly another name for the “Martial Campus” on the Caelian Hill, used for games during religious festivals, especially when the Campus Martius was flooded. By the late Republic, the Campus Agrippae also existed, located on the east side of the Via Lata (modern Via del Corso), which was likely part of the Campus Martius.

However, Rome was just one city in the vast Roman Empire, albeit an exceptional one with nearly a million inhabitants at the start of the Empire. In Italy and the western provinces, smaller campi existed, functioning as public spaces often lined with trees, sometimes with additional facilities like porticoes, swimming pools, latrines, and enclosing walls.

These provincial campi served multiple functions, primarily for the youth of the local elite but were also likely used by gladiators and regular athletes. Considered as significant as the forum, baths, theaters, or amphitheaters, these campi were overlooked later, dismissed as "insignificant material remains." Inscriptions from various cities reflect the importance of these spaces, with local benefactors not only funding construction or renovation but also providing amenities like oil, akin to public baths or Greek gymnasiums.

This generosity is seen in places like Como, where the campus was located near a lake, ideal for swimming. Archaeological discoveries suggest campi were often located on the outskirts of cities rather than in the center. Examples can be found in cities like Pompeii, Herculaneum, Alba Fucens, Narbonne, and Frejus. Some archaeologists even describe these areas as "multi-sport complexes," comparable to those in cities such as Aphrodisias. Additionally, besides the civilian campus, there was also a military campus, where soldiers trained under the supervision of a campidoctor.

The Roman Baths: The Equivalent of the Greek Gymnasium

By the beginning of the Roman Empire, the thermae (public baths) became the central place for physical activity. This is reflected in much of the athletic literature, which frequently references baths. These baths often featured mosaics and artistic depictions of athletes, such as those seen in Ostia and Africa, or in stucco works found in Pompeii and Stabiae. Athletic scenes were commonly portrayed on the walls of these buildings, with examples of such decorations found in Tunisia, Boscoreale, and even as late as 465 AD, as mentioned by Sidonius Apollinaris.

In addition to the palaestrae (exercise areas), swimming pools (natatio or piscina) held significant importance in Roman baths. A prime example is the Antonine Baths in Carthage, which featured a nearly 50-meter-long seaside pool, along with several other pools in the frigidarium and caldarium. These baths, although exceptional in size, highlight the central role of swimming in Roman culture, particularly in regions like Africa where water was more scarce.

Romans and their Love for Swimming

Swimming was more than just a leisure activity; it was seen as an athletic exercise. Even smaller baths had their own natatio, and this tradition extended to private villas, like Pliny the Younger’s famous Laurentine villa near Ostia, which featured a heated pool where swimmers could enjoy a view of the sea. Interestingly, Romans were the only ones of their time to practice swimming as a sport, distinguishing it from bathing. Seneca, for instance, differentiates between lavari (to bathe) and natare (to swim).

Recent archaeological findings, such as those in Baetica, further support this, with swimming pools designed more for athletic activity than hygiene. Romans even categorized different swimming styles, including breaststroke and underwater swimming, as described by Manilius in his Astronomica. One notable example of Roman swimming prowess is Julius Caesar's famous swim during the siege of Alexandria:

‘… The Egyptians sailed up against him from every side, so that he threw himself into the sea and with great difficulty escaped by swimming.

At this time, too, it is said that he was holding many papers in his hand and would not let them go, though missiles were flying at him but held them above water with one hand and swam with the other.’

Roman women likely practiced swimming, as suggested by historical accounts such as the legend of Cloelia. Both Livy and Plutarch recount the story of Roman maidens, including Cloelia, who escaped captivity by swimming across the Tiber River, despite its strong currents. According to the story, they took advantage of the still waters in a river bay, where they had gone to bathe, and seized the opportunity to swim away when they noticed no guards nearby. This tale indicates that swimming was part of Roman women's lives, at least in some circumstances.

Another notable example is Agrippina, who famously survived an assassination attempt in Baiae by swimming to safety, thwarting her son Nero's plot to have her drowned. These examples, while legendary, suggest that Roman women may have been more familiar with swimming than previously thought. (Athletic exercises in ancient Rome. When Julius Caesar went swimming, by Jean-Paul Thuiller)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: