Asarotos Oikos Mosaic: The Unswept Floor of the Roman Elite

The "asarotos oikos", a peculiar and captivating form of art that intrigued the elite and showcased the heights of artistic innovation.

Amidst the lavish villas of ancient Rome, adorned with frescoed walls and marble statues, lay a distinctive and intriguing art form that captivated the elite and demonstrated remarkable artistic ingenuity: the asarotos oikos, or "unswept floor" mosaic.

This unique mosaic style, which flourished during the Hellenistic period and persisted into Roman times, provides valuable insight into the cultural and social fabric of antiquity. The asarotos oikos mosaic attributed to Heraklitos is a prime reason to visit the Gregoriano Profano Museum in the Vatican, where this extraordinary masterpiece of craftsmanship is on display.

A Mosaic of Elite Symbolism and Artistic Illusion

Ehud Fathy is an art historian in Tel Aviv University, who is greatly interested in studying the ways in which images can function as visual representations of the culture, society and practices of their period. Ehud's research focuses on still-life depictions and mystical scenes found in Roman art.

In his work, "The asàrotos òikos mosaic as an elite status symbol" he explores the social significance the asarotos oikos' depictions have held during the late Imperial age, and their relation to the proceedings of the banquet. Ehud Fathy tells us, that one of the more uncommon themes in Roman mosaics is the asarotos oikos, or "unswept floor," which depicts scattered remnants of a lavish meal evenly spread across the floor of a room.

According to Pliny the Elder, this motif was first introduced by the Hellenistic mosaicist Sosos of Pergamon in the second century BCE. Although the original mosaic referenced by Pliny has never been found, later Roman versions of the theme have been uncovered across Italy and the Roman provinces of North Africa, dating from the late first century to the mid-third century CE.

"Pavements are an invention of the Greeks, who also practised the art of painting them, till they were superseded by mosaics.

In this last branch of art, the highest excellence has been attained by Sosus, who laid, at Pergamus, the mosaic pavement known as the "Asarotos œcos;"from the fact that he there represented, in small squares of different colours, the remnants of a banquet lying upon the pavement, and other things which are usually swept away with the broom, they having all the appearance of being left there by accident.

There is a dove also, greatly admired, in the act of drinking, and throwing the shadow of its head upon the water; while other birds are to be seen sunning and pluming themselves, on the margin of a drinking-bowl."

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History

These mosaics have often been classified as decorative or genre scenes, with little research dedicated to their deeper symbolic meanings. The asarotos oikos is frequently associated with xenia depictions—images of hospitality offerings—yet it differs significantly in content and composition.

While xenia mosaics display appetizing arrangements of fruit, vegetables, cheese, and game in domestic settings, the asarotos oikos presents food remnants scattered on a neutral background, evoking a different artistic and cultural message. Discovered exclusively in the homes of the Roman elite, these mosaics required significant financial investment, making it unlikely that their sole purpose was to amuse guests with their trompe-l'œil (deceive the eye) effects.

Instead, they likely functioned as status symbols, representing an intellectual and cultural sophistication understood only by the traditional ruling class.

Detail with a fishbone from a red mullet from the asarotos oikos mosaic. Credits:

Dmitriy Moroz, Alamy

As the political and economic landscape of the late Imperial period shifted, these mosaics may have served as subtle assertions of aristocratic identity and cultural superiority over the rising elite. The most renowned example of an asarotos oikos mosaic was unearthed in 1833 near the Aurelian Wall, south of the Aventine Hill in Rome, during Emperor Hadrian's reign.

It features depictions of fruit, lobster claws, chicken bones, shellfish, and even a small mouse nibbling on a walnut shell. The depicted objects' realism is achieved through skillful color application to produce shadows against the floor's white backdrop. Dating to the early second century CE, it is signed in Greek by the artist Heraklitos and measures 4.05 x 4.05 meters (13.29 x 13.29 feet). Today, it is preserved in the Vatican Museums, as aforementioned.

Another significant mosaic of this type was discovered in 1859 in Aquileia, a prominent Roman city in northern Italy. Originally part of a domus belonging to the upper class, this mosaic, dating to the second half of the first century CE, suffered damage during removal.

It was later reassembled between 1919 and 1922 and is now displayed in the Aquileia Museum. Measuring 2.49 x 2.33 meters (8.17 x 7.64 feet), it covered an entire room, though its central emblema is missing, leaving only partial details of a feline paw and a bird’s wing.

Additional examples of asarotos oikos mosaics have been found in Tunisia, though they are smaller and do not extend across entire rooms. The earliest, discovered at Salonius House in Oudna, consists of five emblemata (60 x 70 cm — ±23 x 27.5 inches each) dating to the late first or early second century CE. These were later repositioned at the center of a grand villa’s floor and are now housed in the National Museum of Bardo.

Another example, found at Maison des Mois in El Djem, dates to 210-235 CE and features a U-shaped frieze, part of the decorative layout common in triclinia. It is currently preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Sousse. A final example was incorporated into the floor of a Byzantine basilica in Sidi-Abich but was completely destroyed upon extraction.

Status, Art, and Mortality

The asarotos oikos mosaics were crafted using the opus vermiculatum technique, which employed tiny tesserae—(Latin for “cubes” or “dice”) pieces that have been cut to a triangular, square, or other regular shape so that they will fit closely into the grid of cubes that make up the mosaic surface—(ranging from 1 to 4 mm) of irregular shapes to create highly detailed and multi-colored compositions.

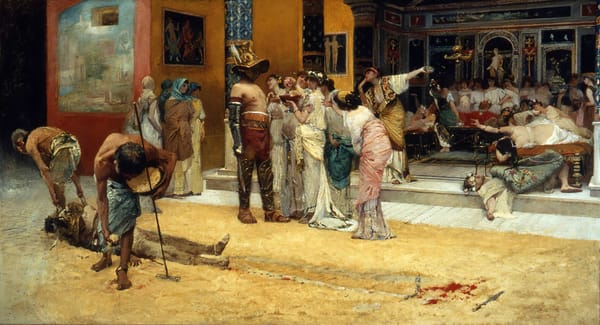

Given their subject matter—depicting food scraps strewn across a dining room floor—it is highly plausible that these mosaics adorned the triclinium, the Roman banquet hall. Their imagery directly referenced the Roman custom of discarding meal remnants onto the floor during feasts.

However, a deeper symbolic function is also suggested: during banquets held in honor of the dead, offerings were made to the deceased by throwing food on the ground.

Detail with a chicken leg from the asarotos oikos mosaic. Credits: Dmitriy Moroz, Alamy

In this context, the asarotos oikos could serve as a permanent artistic representation of symbolic funerary offerings, replacing the actual practice with a more enduring tribute. The revival of the asarotos oikos theme in second-century Rome was not coincidental; it aligned with the Second Sophistic, a cultural movement that sought to revive the glory of Hellenistic traditions, a goal actively promoted by emperors such as Trajan and Hadrian.

This deliberate Philhellenism was an intellectual and political strategy. As Greek culture gained renewed prominence, visual quotations of classical Hellenistic art—such as the asarotos oikos, originally introduced by Sosos of Pergamon—became status symbols for elite Romans. By commissioning these works, wealthy patrons sought to present themselves as erudite connoisseurs, steeped in Greek artistic and philosophical traditions.

The asarotos oikos exemplifies how Hellenistic visual techniques aimed at eliciting emotional responses, such as laughter, surprise, or reflection.

Detail with a mouse and a walnut from the asarotos oikos mosaic. Credits: Dmitriy Moroz, Alamy

Sosos’s innovative motif—depicting the remnants of a meal as an independent artistic subject—reflected a broader artistic trend: a fascination with everyday life and its fleeting nature. The imagery resonated with hospitality traditions, luxurious banqueting customs, and even philosophical reflections on mortality.

Aesthetic Erudition and Social Distinction

Scholar Jeremy Tanner explores the sociological role of art in the Greco-Roman world, emphasizing that artwork functioned as “expressive symbolism”, reflecting social relationships and intellectual hierarchies. In classical Athens, art primarily served political or ritual purposes, functioning as part of daily life and civic identity.

However, in the Hellenistic and Roman periods, art transitioned into the private sphere, where it took on a new social function. A sophisticated elite viewing culture emerged, characterized by aesthetic formalism, a deep knowledge of classical art history, and an ability to engage in artistic criticism. Mastery of these cultural tools allowed elite Romans to distinguish themselves from newly wealthy individuals, who might possess economic power but lacked proper artistic and intellectual refinement.

Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia reflects this elevated approach to viewing art, wherein appreciation requires leisure, silence, and erudition. By the Imperial period, an entire infrastructure of artistic culture had developed: collectors, art dealers, forgeries of classical masters, exhibition halls in private villas, and even art tourism.

The act of viewing art was no longer passive; it was a learned skill, an intellectual exercise requiring training in rhetoric, philosophy, and mythological knowledge. This elitist approach to art consumption was designed to exclude those without proper education, reinforcing social hierarchies in an era of increasing class mobility.

Banquet Imagery and the Philosophy of Death

The asarotos oikos mosaics did not merely serve as banquet decorations—they encapsulated an elite philosophical worldview. The theme aligned with the Roman obsession with mortality, deeply rooted in Epicurean and Stoic traditions.

In both literature and visual culture, banqueting was metaphorically tied to life’s transience. Lucretius, Horace, and Martial all reference the notion that one should enjoy life’s pleasures while they last, for death is inevitable. This idea is epitomized by the famous saying from the pseudo-Vergilian Copa:

"Vivite," ait, "venio"—Live, for I am coming.

During banquets, miniature skeletons were passed among guests as memento mori, reinforcing the idea that pleasure should not be delayed. This motif appears in Petronius’ Satyricon, where the freedman Trimalchio presents a silver skeleton during a lavish feast, proclaiming:

"Let us live, then, while it goes well with us."

The asarotos oikos visually embodies this philosophy. The scattered meal remnants symbolize the impermanence of life and earthly pleasures—once rich and abundant, now mere debris. The juxtaposition of luxury and waste suggests a dialectic of nourishment and decay, fertility and withering, life and death.

The Vatican Asarotos Oikos Mosaic: A Program of Elite Discourse

The most famous asarotos oikos mosaic, attributed to Heraklitos, discovered in 1833 near the Aurelian Wall on the Aventine Hill—a district known for its affluent Roman villas, dating to the early second century CE, is now housed in the Vatican Museums. The decorative program of the room it adorned was highly sophisticated:

- Three outer friezes mirrored ceiling decorations.

- Two inner friezes depicted scattered food scraps (asarotos oikos theme).

- A third frieze showcased Dionysian masks and artifacts, reinforcing the banquet’s association with wine, revelry, and mystery cults.

- The central emblema (now lost) may have depicted Sosos’ "drinking doves," another motif referenced by Pliny.

- The Dionysian masks visually connect the theme of banqueting with the metaphor of life as a theatrical performance, a concept explored by Lucian and Aristophanes.

Lucian’s satirical dialogues compare human existence to a stage play, where individuals temporarily adopt different roles before death strips them of their status. This philosophical perspective is echoed in elite Roman culture, which valued self-control, intellectual engagement, and an ability to interpret multi-layered artistic and rhetorical symbols.

A Last Stand Against Social Change

The elite commissioning of asarotos oikos mosaics was not simply an artistic indulgence—it was a reaction to the shifting social order of the Imperial period. As newly wealthy individuals gained political and economic power, Rome’s traditional aristocracy sought to reaffirm its superiority through cultural exclusivity. These mosaics served as a final bastion of distinction, demanding an elite education to fully decode their meaning.

Beyond intellectual posturing, the asarotos oikos also tied into mystical religious beliefs. In addition to referencing Roman funerary rites, these mosaics hint at the esoteric traditions of the Dionysian Mysteries and the cult of Osiris and Isis, which promised their initiates a privileged afterlife. Thus, the asarotos oikos thematically links hedonistic pleasure, philosophical reflection, and religious aspiration—all expressions of the Roman elite’s attempt to grapple with mortality in a rapidly changing world.

Heraklitos crafted an intricate mosaic for the floor of the triclinium, welcoming visitors with a design featuring theatrical masks, ceremonial items, and the artist's own signature at the entrance. The primary decorative element of the mosaic showcased a detailed Nilotic scene, which has largely been lost over time.

Surrounding the room's perimeter, the "assarotos oikos"-themed mosaic depicted the leftovers of a feast against a white backdrop, portraying what would typically be discarded. It's fascinating to attempt to discern what Heraklitos included in this remarkable floor design... various fruits, leafy greens, claws of lobsters and crabs, shells of clams and oysters, sea urchins, chicken bones, and nutshells, including a small mouse nibbling on a walnut shell (as pictured above).

The artist's ability to convey depth through the use of contrasting colors and creating shadows on the white floor, is simply impressive.

Detail with a sea shell from the asarotos oikos mosaic. Credits: Dmitriy Moroz, Alamy

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: