We Researched the Roman Empire‘s Presence in the Orient: Here is What we Found

The Roman Empire left a notable architectural and cultural footprint in the East, where Roman monuments, cities, and even temples still stand as remnants of its reach.

The Roman Empire's reach extended far beyond the Mediterranean, influencing regions across the Eastern world in ways that left lasting marks on architecture, culture, and commerce. From the bustling city of Palmyra in Syria to the majestic ruins of Baalbek in Lebanon, Roman monuments in the East tell stories of an empire that bridged diverse civilizations.

Beyond physical monuments, Rome's trade with the Orient introduced exotic goods such as silk, spices, and precious stones, enriching Roman life and expanding its economic influence. We wanted to explore the dynamic relationship between Rome and the East, highlighting the architectural legacies, the complex web of trade routes, and the cultural exchanges that shaped both worlds.

Rome, the East and the Monster in the Closet

In 29 B.C., Octavian’s grand triumph marked Rome's conquest of the Mediterranean, especially Egypt, fulfilling Romans’ hopes for security and dominance. Octavian, now Augustus, faced a complex legacy; his power depended on dispelling fears of “Orientalism,” a growing concern tied to Julius Caesar’s alleged intent to rule from Alexandria and Antony’s overt ties to the East.

Romans feared Eastern influence on their government and traditions, a sentiment Octavian shrewdly amplified in his rivalry with Antony. To reassure his people, Augustus avoided titles and symbols of monarchy, focusing instead on Italian traditions and monumentalizing Rome as the empire's heart.

Eastern influence, however, remained a double-edged sword. While Rome relied heavily on Egyptian grain, Augustus sought to reduce this dependence by boosting agriculture in Africa, Spain, and Gaul. Egypt, though lucrative, was restricted as Augustus made it his private estate, wary of any Roman who might use it as a power base. This suspicion persisted, as seen in Vespasian’s seizure of Egypt to cut Rome’s grain supply during his bid for power in 69 A.D.

In religion, Augustus reinforced traditional Roman gods while discouraging foreign cults like those of Isis and Anubis. Later emperors echoed this, even targeting early Christians as they tried to curb the influence of Eastern practices.

Over time, however, Roman governance gradually adopted an Eastern style, culminating in the 4th century under Constantine, who established an Oriental-style monarchy in Byzantium. By then, the empire had shifted from the ideal of a Roman citizen serving the state to a model of divine kingship, surrounded by the symbols and rituals of an Eastern court. (The Fear of The orient in The Roman Empire, by M.P Charlesworth, M.A. Cambridge Historical Journal)

Roman Monuments and Influence in the Eastern Provinces

“As I contemplate the greatness of your fortune and your spirit, it seems entirely appropriate to point out to you construction works that are worthy of your eternal renown and your glory, and which will be as useful as they are splendid."

With these words, Pliny began his letter to Trajan, encouraging him to support a proposal to build a canal connecting Lake Sapanca in Nicomedia with the Sea of Marmara. Pliny closed by noting that, where the kings of Bithynia had fallen short, the emperor could triumph: “What they only began, may you bring to a successful end.”

For rulers, constructing public or religious buildings has always been essential for the welfare of their communities. In the Graeco-Roman world especially, public construction reflected a tradition of generosity that guided aristocratic behavior. As one inscription from the Actors' Guild at Smyrna commemorates, Marcus Aurelius Iulianus, twice Asiarch, priest of Bacchus, and caretaker of the emperors' temples, was celebrated for his reverence, his civic dedication, and his extensive building projects on behalf of his city and its associations.

Even more striking is the detailed account in The Jewish War by Josephus, listing the vast building projects of Herod the Great: in Tripolis, Damascus, and Ptolemais, he funded gymnasia; in Byblos, he constructed a city wall; in Berytus and Tyre, he added baths, colonnades, temples, and marketplaces; in Sidon and Damascus, he built theaters; in coastal Laodicea, he commissioned an aqueduct; and in Ascalon, he constructed baths, majestic fountains, and cloistered quadrangles.

To Rhodes, he repeatedly sent funds for naval construction and restored the Temple of Apollo to a grandeur surpassing its former glory. His generosity extended even further to Lycia, Samos, and the entire region of Ionia, supporting every local need. Athens, Sparta, Nicopolis, and Mysian Pergamum all bear witness to Herod’s contributions, as does the wide street in Syrian Antioch, previously impassable due to mud, which he paved with polished marble and covered with colonnades for its full two-and-a-quarter-mile length.

While the motives behind such public projects are rarely spelled out, they often combined civic benefit with personal prestige for the benefactor, as buildings offered lasting legacies that would preserve the donor's memory long after their passing. The act of erecting public buildings was central to civic duty, creating both a tradition of generosity and a public expectation that no Roman emperor, even if he had wished, could escape.

None ever attempted to do so.

Imperial building projects are an enduring theme in imperial biographies, from Augustus—who famously declared he had transformed Rome from a city of brick into one of marble—to his successors and to Constantine, whose new capital rivaled Rome in splendor, and continued well into the Byzantine era.

Some of the most prominent builders took a personal interest in these projects. Hadrian, for instance, is said to have tried his hand as an architect, and it’s possible that the remarkable builder Marcus Agrippa, besides his official duties, helped design the grand roof spans of the Odeon in Athens and the Temple of Zeus at Heliopolis in Syria, where he had established a veteran colony in 14 B.C.

The most striking examples of imperial building projects naturally exist in Rome itself, where we now know a specialized architectural and construction team operated under direct imperial patronage, producing the monumental public works of the Flavian and Trajanic eras, culminating in Hadrian’s restoration efforts for the grandeur of the Augustan city.

These grand works in Rome reflected the emperor’s relationship with the city and its people. Similarly, the emperors’ roles as builders throughout Italy and the provinces were significant, though less prominently recorded and more challenging to interpret. Such imperial construction projects reinforced the bond between Rome’s rulers and their provincial subjects, giving them a broader and deeper significance.

Credits: UNESCO, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Imperial Construction: Military and Civic Projects Beyond Rome

In the Roman Empire, construction projects outside of Rome itself typically fell into two main categories: military and administrative structures for the Empire’s security, and civic projects like temples, bathhouses, theaters, and porticos, often funded or encouraged by the emperors.

While the distinction between these two categories is helpful, there was often significant overlap. Military installations, such as legionary fortresses, forts, and key roadways, were typically planned at a central level by emperors or their representatives, though surprisingly, local communities sometimes financed or provided labor for these projects. Major highways, crucial for military and administrative movement, were often built using compulsory local labor, with inscriptions showing that military units were only occasionally responsible for their construction.

In addition to military installations, emperors supported fortified relay posts along major roads for official travelers. Records show Nero, Trajan, and Marcus Aurelius constructing rest houses and fortified posts on roads across Thrace and Galatia, while Hadrian and Augustus set up similar sites along the desert route from the Nile to Coptos. Yet, even in these projects, local patrons sometimes took charge; for instance, in Lycia, a couple converted a gymnasium into a rest house, possibly to accommodate troops during Trajan’s Parthian campaign.

Military personnel were frequently engaged in civilian construction when not involved in combat. For example, under the reign of Emperor Probus, soldiers in Egypt built not only irrigation channels and drainage systems but also civic structures like temples, basilicas, and bridges. Evidence suggests that soldiers were employed almost as often in large-scale civic constructions as in military-related ones, primarily in building grand structures such as temples or bathhouses.

The military’s architectural expertise was as valuable as its manpower. Pliny’s numerous requests to Trajan for skilled architects in Bithynia reveal the need for military expertise to assess local building projects. Trajan eventually approved a canal scheme combining military architectural knowledge with local labor.

Hadrian’s reign saw a similar use of military architects for large projects, as in Boeotia, where military engineers supervised the draining and canalization of Lake Copais. The military’s role in civilian projects is exemplified by the case of a veteran engineer who fixed a misaligned water conduit in Numidia using teams of soldiers and auxiliaries. Even for standard projects, such as those at Delphi, military supervisors were valued, as evidenced by the case of a frumentarius from the First Italic Legion, granted citizenship for his excellent oversight of Hadrian’s building projects there.

Thus, Roman imperial construction in the provinces was a blend of centralized planning and local collaboration, with military skills seamlessly integrated into the civic sphere. The overlap of military and civilian projects demonstrates the practical adaptability of the Roman Empire, using its resources to reinforce both its infrastructure and its cultural influence across the provinces.

Building Security: The Role of City Walls in Rome’s Provincial Defense

Roman city wall construction blurred the lines between military and civic efforts, as civilian labor and resources often supplemented military expertise, especially in provincial fortifications crucial for the Empire's defense. Emperors sometimes directly funded city walls, as with Augustus, who reportedly built walls and gates for Roman colonies like Nemausus and Vienna in Gaul, and a wall and towers for lader in Dalmatia. In the eastern provinces, the Roman-style fortifications at Pisidian Antioch, likely initiated under Augustus, suggest similar imperial responsibility.

At times, private citizens contributed significantly to wall construction. In Odessus, under Tiberius, a local funded part of the walls amid early Empire threats. During the 70s A.D., the perceived Parthian threat led to local-funded walls at Gerasa, though likely ordered by Rome or its governor. Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian reinforced Harmozica’s walls in Iberia in 75 A.D., emphasizing direct imperial intervention.

Other examples include Laodicea and Hierapolis, where a private imperial freedman financed fortification efforts in the 80s A.D., while the Roman proconsul supervised construction. As pressures mounted on the northern frontiers in the second century, legates fortified Danubian and Balkan cities, such as Serdica and Philippopolis, supported by military resources, an approach that expanded significantly in the third century.

With the Empire in crisis, third-century wall-building efforts varied. For example, Gallienus assigned architects to fortify West Pontic cities, and funds were provided to Dera'a in northern Arabia for defenses in 262/3 A.D. Asia Minor cities like Sardis, Ephesus, and Ancyra saw local officials, magistrates, and governors credited with these constructions, though it remains unclear who initiated or financed them. Nicaea’s inscriptions further highlight this ambiguity: while one gate mentions imperial responsibility under Claudius Gothicus, another attributes the wall’s dedication to the city and Senate.

Despite the complexity, the pattern shows that wall construction usually involved cooperation between imperial authorities and local communities, with initiatives and funding often jointly shared, reflecting an adaptable approach in times of varying threats. (Imperial Building in the Eastern Roman Provinces, by Stephen Mitchell, Department of the Classics, Harvard University)

Roman Trade with the Far East

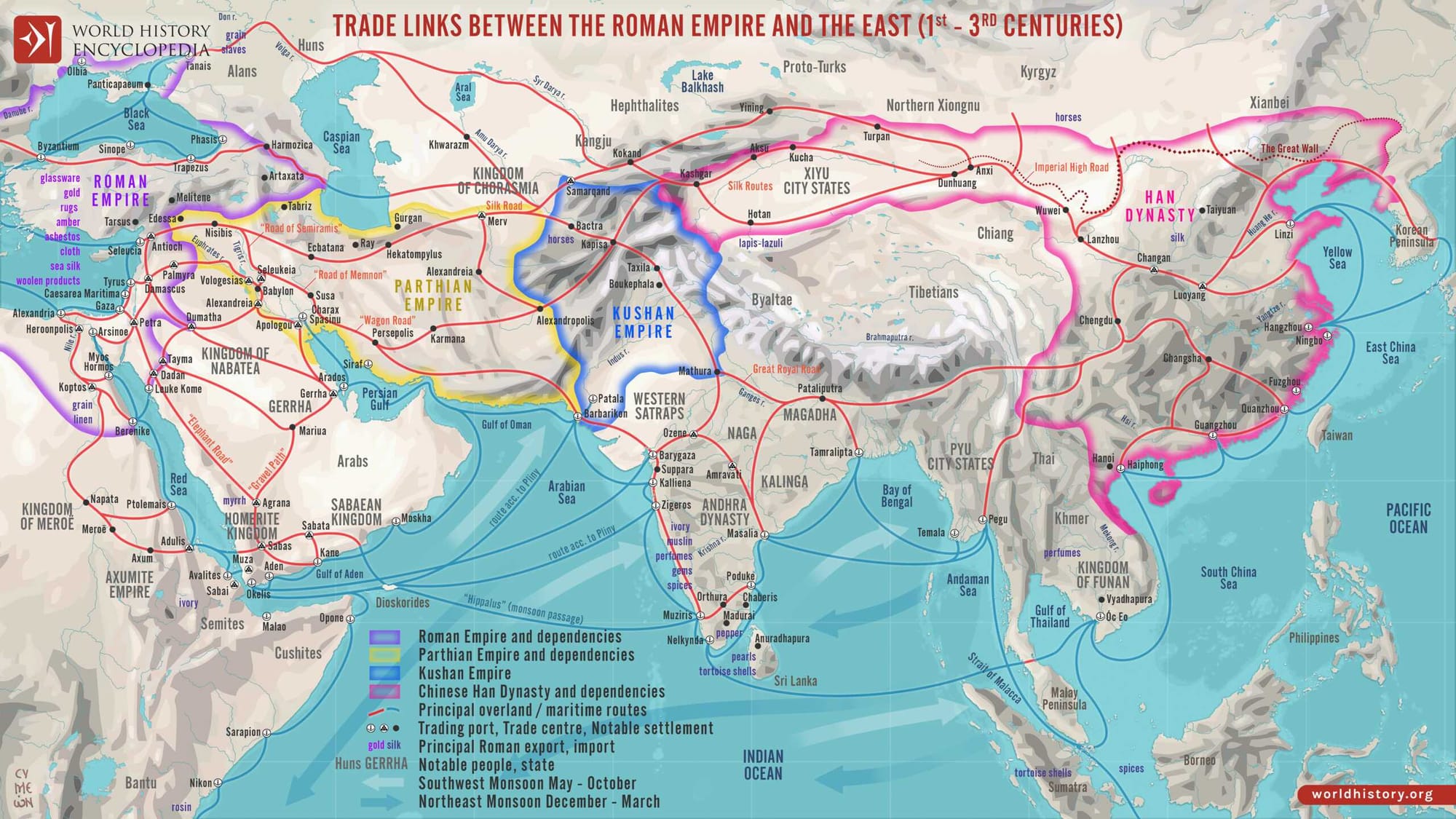

Between the first and third centuries, Roman trade with the Far East flourished, thanks to overland caravan routes and the discovery of trade winds that enabled maritime travel. Although Roman sources sometimes confused the overland and sea routes to the East, both paths provided access to luxury goods like silk, spices, and precious stones.

Caravan routes through Asia connected the Roman Empire to China, passing through the Pamirs to China’s ancient capital, Singan-fu.

A possible representation of a caravan, travelling through Asia. Illustration: Midjourney

Silk merchants had been using this route since the second century B.C. Sea routes were also crucial, linking Rome with India’s west coast and Ceylon, from where goods continued on to Southeast Asia and China. Roman sailors relied on seasonal trade winds, called the Hippalus winds, for navigation, reaching the Malabar coast of India within 40 days during the summer. Roman ships faced challenges like pirate attacks near the Tamil ports, where merchants would stop to exchange goods before returning with the southeast trade winds in December.

The trade route extended beyond India, where Tamil ports on the Bay of Bengal connected with “Golden Chersonese” (likely Southeast Asia) and Kattigara, which Roman and Chinese sources indicate might have been on the Red River in present-day Vietnam. Chinese records confirm interactions with the Roman world, sometimes referring to the Empire as “Ta-Tsin.” Chinese records of gifts and embassies also illustrate exchanges that linked China with India and Rome.

Despite limited direct Roman contact, records from Tamil literature, coinage, and trade references confirm Roman commercial influence in South Asia. Rome’s primary engagement was through Indian ports, while long-distance voyages to China remained rare. Occasionally, individuals traveled farther east, but Roman shipping in East Asia was infrequent. (Navigation to the Far East under the Roman Empire, by Wilfred H. Schoff, Journal of the American Oriental Society)

Puteoli, a key Italian port town for Rome, played a vital role in trade with the East. Known for receiving the Alexandrian grain fleet, it also likely handled high-value items like Tyrian purple dye. Luxury goods from distant regions—such as spices, silk, and frankincense from Arabia, China, and India—probably passed through Puteoli as well.

While Puteoli has not revealed eastern artifacts comparable to Pompeii's findings (e.g., an Indian ivory statuette of a voluptuous female figure), it does offer epigraphic evidence. Inscriptions from both the Greek world and Italy indicate Nabataean presence in the Mediterranean. It is believed that: first, Puteoli hosted the only permanent Nabataean community in the Mediterranean; second, that this community created a trade link between Nabataean merchants and Roman buyers, fostering trust and communication essential for commerce.

Strategically positioned between the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean, the Nabataean Kingdom was ideally situated for East-West trade. Its peak commercial influence spanned from the mid-second century BCE until just before its annexation by Rome in 106 CE. Although historical records suggest that Nabataean presence faded quickly under Roman rule, traces remain. Apuleius, for instance, mentions Nabataean merchants in a poetic passage evoking exotic eastern peoples, but by the 160s CE, they may have already become a distant memory.

Roman texts highlight that the Nabataeans’ primary wealth came from the Arabian aromatics trade.

Arabian incense and fragrance were among the top prized trade commodities in the Roman Empire. Illustration: Midjourney

Diodorus of Sicily describes them as the wealthiest Arab tribe, noting that many transported frankincense, myrrh, and valuable spices to the coast from "Arabia Eudaemon." Other authors like Strabo and Pliny the Elder portray the Nabataeans as intermediaries who did not produce goods themselves. Instead, they transported products from the South and East, moving them westward—a route that formed the basis of their commerce and prosperity.

The Nabataean trade network relied on two main overland routes, with sources well-documented. Strabo notes that the Nabataeans acquired incense from the Minaeans and Gerrhaeans, tribes from present-day Yemen. Goods traveled along a route paralleling the eastern coast of the Red Sea. Pliny the Elder adds that northbound goods passed through Gebbanitae territory, where this Arabian tribe charged a toll for passage, effectively controlling trade access to the Mediterranean. (Roman Trade with the Far East: Evidence for Nabataean Middlemen in Puteoli, by Taco Terpstra)

Trading Silk between China and the Empire

The height of the silk trade between China and the Roman Empire, was taking place specifically between 90 and 130 A.D., a period marked by significant commerce and relatively stable political conditions along the trade route.

The primary trade route saw silk move overland from northern China, passing through the Kushan kingdom (spanning parts of Central Asia and northern India) and Parthia, before arriving in the Roman Empire. This era of peace among major powers along the route facilitated a steady flow of luxury goods. Both the Kushan and Parthian empires played intermediary roles, with Parthians at the western end actively blocking direct contact between Roman and Chinese merchants to secure their position as middlemen and profit from the trade.

Romans highly prized silk, while the Chinese valued gold and silver from Rome.

A silk trader in China, selling his merchandise to an ancient Roman merchant. Illustration: Midjourney

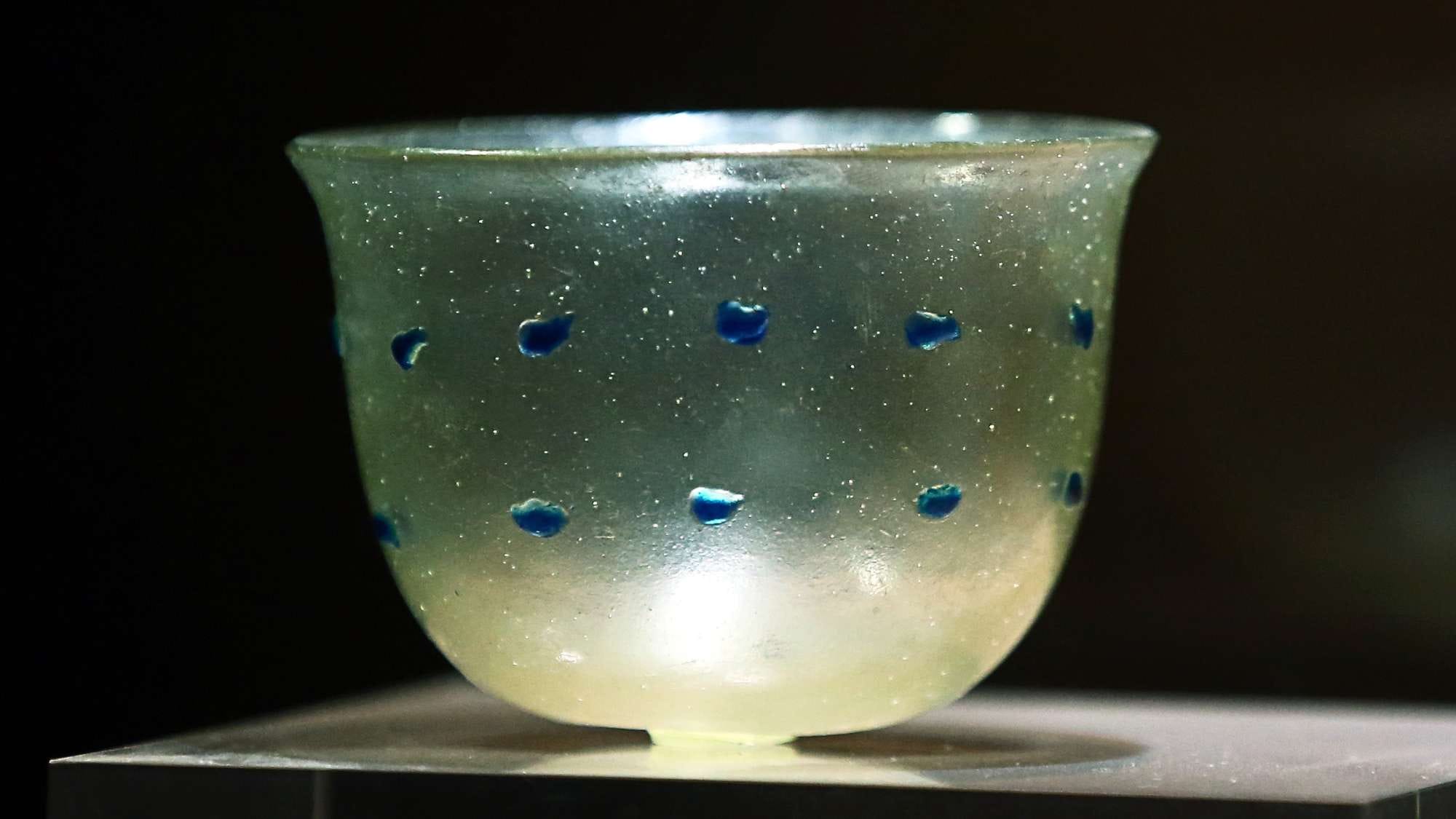

In addition to silk, the trade included other luxury items such as glass, coral, and fine textiles from the Levant, reflecting an extensive demand for exotic items and a sophisticated system of exchange in both empires. Several cities along the route, including Palmyra, Petra, and Dura-Europos, became prominent commercial centers due to their strategic locations and bustling trade activities. Archaeological finds, such as inscriptions and trading contracts, highlight the organization and intensity of the silk trade and the wealth it brought to these cities.

However, after 130 A.D., political instability along the route disrupted trade. The Chinese faced declining control over their western territories, and escalating tensions between Rome and Parthia hindered safe passage. This shift led to a gradual decline in the silk trade’s intensity as routes became less reliable and more dangerous.

In tracing the intricate web of connections between Rome and the East, we witness a remarkable era of cultural and economic exchange, with the flow of goods like silk, spices, and incense reflecting the diverse interests and ambitions of empires. While cities like Puteoli and Petra thrived as trade hubs, connecting distant worlds through their ports and caravan routes, the legacy of these exchanges is more than material.

The Roman Empire’s relationship with the Orient shaped perceptions, policies, and even myths that resonated across centuries, with each empire in the chain of trade leaving a unique mark on the cultural and economic landscapes of their time. As we conclude this exploration, it becomes clear that the ancient trade routes were not merely paths of commerce but powerful symbols of how interconnected the ancient world truly was, laying foundations that still echo, in our globalized society today.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: