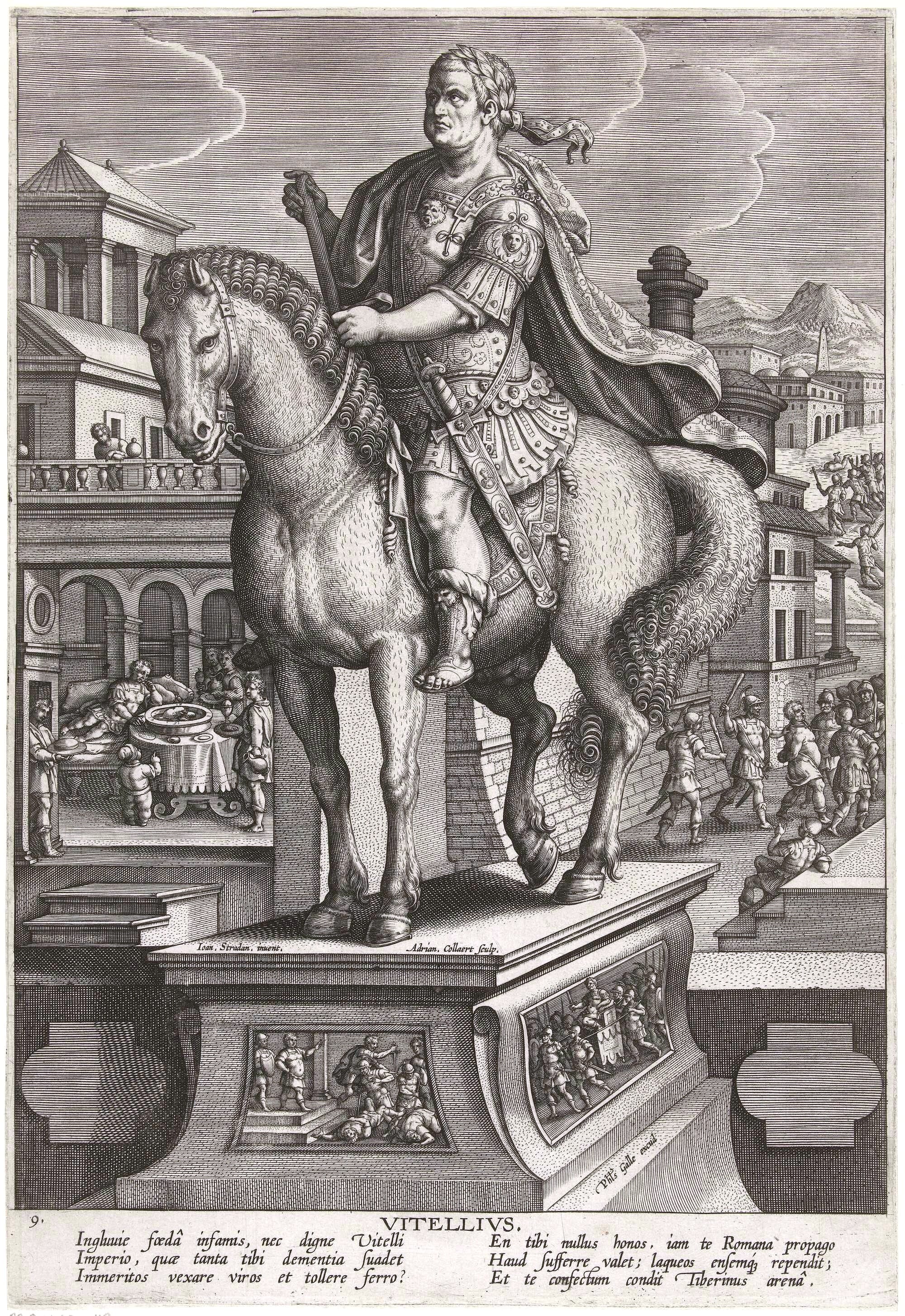

Vitellius: The Emperor Rome Raised – and Destroyed

Vitellius is remembered as Rome’s glutton emperor. Yet beneath the hostile portraits of civil war lies a more complicated ruler – one whose brief reign reveals as much about historical narrative as about power itself.

In the chaotic year of 69 CE, Rome did not merely change emperors – it exposed the fragility of imperial power. Amid the rapid succession of claimants who rose and fell with the loyalty of legions, one figure would be remembered less for military strategy or political vision than for appetite. Aulus Vitellius entered Rome as emperor carried by the momentum of civil war; he would leave it dragged through the streets. Between those two moments lies a reign that later writers reduced to excess and indulgence – yet beneath the caricature stands a more complex story of authority in collapse.

A Tyrant by Tradition – Or a Casualty of Narrative?

The surviving ancient portraits of Vitellius are overwhelmingly hostile. In the works of Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio, he appears as indolent, self-indulgent, and politically incapable – a ruler defined by excess rather than authority. Such uniform negativity reflects the shadow cast by the victorious Flavian dynasty, whose rise depended on the discrediting of their predecessor.

These authors drew on a shared historical tradition about the collapse of Nero’s regime, the civil wars of 68–69 CE, and the emergence of Vespasian. Earlier scholarship sought a single lost source behind their similarities; more recent work recognises a broader network of parallel accounts. What matters is not merely common origin but narrative shaping. Each historian moulded inherited material to serve his own literary and ideological purposes.

The case of Cassius Dio is especially revealing. His account of Vitellius survives only in Byzantine epitomes and excerpts – through Xiphilinus, Zonaras, and the Excerpta Constantiniana – yet enough remains to reconstruct its structure. Dio certainly preserved the familiar accusations of luxury and debauchery. But unlike Tacitus or Suetonius, he also recorded moments of clemency, legislative moderation, and constructive relations with senate and people.

These passages complicate the standard image. Where Tacitus often treats similar anecdotes with irony, casting Vitellius’ gestures as hollow pretence, Dio isolates them as evidence of qualities expected of a civilis princeps – the “good emperor.” His narrative method, shaped by character sketches rather than strict chronology, allowed room for selective commendation within an otherwise negative reign.

The result is not rehabilitation but tension. Vitellius remains flawed, yet he is not reduced entirely to caricature. In Dio’s hands, the emperor becomes a figure through whom competing standards of imperial behaviour are tested – a ruler whose brief principate exposes how history itself could magnify vice, soften virtue, or rearrange both according to the needs of narrative and memory.

Clemency in a Time of Civil War – Dio’s Unexpected Vitellius

Book 65 opens with familiar invective: Vitellius is introduced as devoted to

“extravagance and licentiousness” (τῇ τε τρυφῇ καὶ τῇ ἀσελγείᾳ προσκείμενος),

followed by anecdotes of gambling, monumental banquets, and the infamous million-sesterce dish. Administrative detail is minimal, a consequence of Dio’s biographical method, which separates character flaws from deeds worthy of praise.

The tone shifts in 65.6:

“Οὕτω δὲ βιοὺς οὐκ ἄμοιρος ἦν παντάπασι καὶ καλῶν ἔργων.”

Vitellius, though morally compromised, was

“not completely without good deeds.”

He retained the coinage of Nero, Galba, and Otho, confirmed their grants, forgave tax arrears, refrained from confiscations, spared most of Otho’s supporters, respected their families’ property, honoured the wills of fallen enemies, and barred senators and equestrians from degrading performances.

“And he was praised on account of these things.”

These gestures align with the ideal of clementia – the virtue of the ἀγαθὸς αὐτοκράτωρ. Tacitus recounts similar episodes but undermines them, casting mercy as weakness or self-interest; Suetonius largely omits or subverts them. Dio, by contrast, isolates such acts as evidence of imperial restraint.

The difference reflects perspective. Writing after witnessing the brutal purges of Septimius Severus and the confiscations following Geta’s murder, Dio recognised in Vitellius’ leniency something conspicuously absent in his own age. By distinguishing βίος from ἔργα, he preserved space for measured praise within an otherwise negative reign.

Arena, Theatre, and Imperial Dignity – Performing the civilis princeps

Public entertainment was not mere diversion. The theatre, circus, and arena formed a political stage on which the emperor displayed – and risked – his authority. Although Dio disapproved of the games, he recognised that attendance was part of imperial duty: at such events a princeps could exhibit comitas, receive acclamations, and be judged by the people. Yet enthusiasm had limits. To participate personally, rather than observe with dignified restraint, was a breach of imperial decorum.

Vitellius’ passion for chariot racing earned predictable censure, especially for

“rubbing down the racing horses in the clothes of the Blues.”

These charges echo the hostile tradition preserved by Tacitus and Suetonius. Yet Dio distinguishes between indulgence and conduct befitting a ruler.

Under the heading of his “good deeds,” Vitellius is said to have forbidden senators and equestrians from fighting as gladiators or appearing on stage in public spectacles. The account concludes simply that “for these things he was praised.” At a time when Nero had forced members of both orders to perform in the arena – conduct Dio describes elsewhere as utterly shameful and shocking – this decision signalled a restoration of proper social boundaries.

For a senator like Dio, who had personally witnessed Commodus fight as a gladiator and Caracalla race chariots in public, such restraint mattered.

Dio also notes that Vitellius attended the theatre regularly and that the crowd became attached to him as a result. The same wording is used for Otho and Didius Julianus, but in those cases frequent theatre attendance is presented as flattery and weakness. Here, however, the tone is more balanced. Tacitus, by contrast, treats the very same behaviour as hollow performance: actions that might have seemed pleasing and popular are dismissed as vulgar and undignified because of Vitellius’ earlier life.

Dio further notes that Vitellius “Ἐπεφοίτα… τοῖς θεάτροις συνεχῶς,” and that the crowd became attached to him. Similar phrasing is used of Otho and Didius Julianus, yet in those cases theatre attendance signals flattery and weakness. Here, the tone is measured. Tacitus, by contrast, undermines the same behaviour as theatrical pretence: actions “grata sane et popularia” are dismissed as “indecora et vilia” because of Vitellius’ past.

The divergence is revealing. Tacitus exposes performance; Dio assesses propriety. In Dio’s reconstruction, Vitellius attended, observed, and refrained from degrading participation. Even an emperor notorious for excess could, in the arena and theatre, act in accordance with the standards of a civilis princeps.

Dining as Equals – Vitellius and the Senate in Dio’s Account

Dio’s final positive assessment of Vitellius concerns his relationship with the Roman elite, especially the senatorial order. In one passage, Vitellius is shown dining with the most powerful men without arrogance, honouring former companions, and not distancing himself from those who had known him before his rise. Unlike rulers who, once elevated, despised their earlier associates, Vitellius treated senators as social equals.

For Dio – who had personally experienced humiliation under Caracalla and had seen emperors favour freedmen and soldiers over senators – such behaviour mattered. Dining practices, in his view, revealed an emperor’s character.

A second episode reinforces this impression. When the senator Helvidius Priscus openly challenged him in the senate, Vitellius did not retaliate. Instead, he told the fathers of the senate not to be disturbed if “two men of your order” disagreed. The incident was interpreted as an act of magnanimity. Where Tacitus portrays the same exchange as arrogance and self-serving comparison with Thrasea Paetus, Dio presents it as restraint and respect for senatorial dignity.

For him, this quality – clemency and measured conduct toward fellow aristocrats – was a defining feature of good imperial rule.

Yet Dio’s praise is limited. After noting these acts of affability and moderation, he returns to a largely negative portrait: imitation of Nero, extravagant banquets, and behaviour that sensible observers regretted. The shift reflects his method – separating character assessment from narrative – and allows Vitellius to emerge not as a simple caricature of vice, but as a ruler whose conduct, at moments, met the standards Dio believed an emperor ought to uphold. (The Conduct Of Vitellius In Cassius Dio's Roman History" by Franz Steiner Verlag)

The Survivor at Court: Vitellius and the Fall of Messallina

The execution of Valeria Messallina in 48 CE is usually told as the triumph of the freedman Narcissus over a reckless empress. In Tacitus’ account, Lucius Vitellius appears only briefly, depicted as hesitant and politically timid. Yet the timing of events invites closer scrutiny. If Messallina’s affair with Gaius Silius had been as public and dangerous as reported, why did Narcissus wait nearly a year before acting?

The delay suggests that isolating Claudius was not enough. Messallina’s allies – especially Vitellius – had to be neutralised first. His earlier role in the forced prosecution of his friend Valerius Asiaticus in 47 CE may have altered his loyalties. Compelled to participate in the destruction of a long-standing associate, Vitellius likely emerged embittered but cautious. Rather than openly opposing Messallina, he may have waited for a moment when silence would be more powerful than intervention.

When Narcissus finally moved against the empress, Vitellius did nothing. That absence of defence proved decisive. His later portrayal as passive and fearful may not reflect weakness, but deliberate self-preservation. By minimising his involvement in her fall, he avoided provoking Agrippina and protected himself against possible revenge from Messallina’s children. In a court governed by shifting alliances, survival often depended less on bold action than on knowing precisely when to withdraw. ("The Role of Lucius Vitellius in the Death of Messallina" by David Woods)

The Crowd Didn’t Change – Power Did

Vitellius’ rise and fall is often used to repeat the old cliché of inconstantia plebis – the “unreliable crowd.” Tacitus captures the brutality of the turnaround with one unforgettable line:

“The mob reviled the dead man with the same heartlessness with which they flattered him when he was alive.”

The same people who cheered him at the start applauded his death when Antonius Primus’ men entered Rome.

Yet the reversal wasn’t driven first by the masses. The sharper pivot came from above. Otho’s leading officers hurried to Vitellius and claimed they had secretly opposed Otho all along. The Arval Brothers quietly rewrote their public loyalty, altering names on an inscription as the political wind shifted – and later erasing Vitellius’ name after his fall.

When the primores civitatis saw the Flavian advance becoming inevitable, they were quickest to abandon Vitellius and attach themselves to Flavius Sabinus. The crowd followed the reality that the elite had already accepted: the regime was collapsing.

Vitellius’ early success also helps explain the speed of the later disaster. He rose with startling ease – a classic “military Caesar,” acclaimed by the Rhine legions in early January 69 and carried into power on consensus and army loyalty. His entry into Italy, the defeat of Otho at Bedriacum (14 April 69), and Rome’s formal recognition created a sense that the struggle was over when it was not.

Crucial forces – especially the Danube armies – remained intact, and the new ruler behaved like a victor securing a settled throne rather than a contender still balancing an empire of rival armies.

From that misread situation, the narrative turns to a pattern: strategic sluggishness, political inconsistency, and a failure to bind defeated factions into a workable settlement. The result wasn’t simply “fickle people.” It was a ruler who repeatedly looked in two directions at once, lost the confidence of the upper orders first, and then discovered – too late – that popular enthusiasm cannot survive a collapse of credibility. Tacitus’ earlier description of the crowd during civil war, tense and listening for every sound, fits the mood perfectly:

“There was no uproar, no quiet, but such a silence as accompanies great fear and great anger.”

("Vitellius and the "Fickleness of the Mob" by Z. Yavetz)

The emperor who entered the capital on the strength of military consensus misread the fragile geometry of power that sustained him. His leniency toward former enemies, his gestures toward the senate, and even his restraint in the arena reveal a ruler capable of acting within recognised standards of imperial conduct. Yet these moments of moderation were undermined by hesitation, inconsistency, and a failure to understand that civil war does not end with a single battlefield victory.

When the Danube legions advanced and elite confidence shifted, Vitellius discovered what every ruler of 69 CE would learn: legitimacy in a civil war is never stable. The upper orders recalculated first. The inscriptions changed. The allegiances adjusted. The crowd, far from initiating the reversal, responded to a political reality already decided elsewhere.

Tacitus’ image of a mob that flatters in life and insults in death remains unforgettable. But the sharper lesson lies beneath it. Popular enthusiasm could not survive a ruler who appeared uncertain at the decisive hour. Once Vitellius hesitated between abdication and resistance, between private survival and public command, he ceased to be an emperor and became, in Tacitus’ words, merely “a cause of war.”

History remembered him as a glutton. Yet the deeper failure was not appetite, but instability – the inability to align gesture, policy, and power at a moment when the empire demanded coherence. In that sense, Vitellius was less an aberration than a symptom: a ruler exposed by the very civil conflict that had elevated him.

Suetonius’ description of the events that led to his assassination is horrifying:

"The foremost of the army had now forced their way in, and since no one opposed them, were ransacking everything in the usual way.

They dragged Vitellius from his hiding-place and when they asked him his name (for they did not know him) and if he knew where Vitellius was, he attempted to escape them by a lie.

Being soon recognised, he did not cease to beg that he be confined for a time, even in the prison, alleging that he had something to say of importance to the safety of Vespasian. But they bound his arms behind his back, put a noose about his neck, and dragged him with rent garments and half-naked to the Forum.

All along the Sacred Way he was greeted with mockery and abuse, his head held back by the hair, as is common with criminals, and even the point of a sword placed under his chin, so that he could not look down but must let his face be seen.

Some pelted him with dung and ordure, others called him incendiary and glutton, and some of the mob even taunted him with his bodily defects. He was in fact abnormally tall, with a face usually flushed from hard drinking, a huge belly, and one thigh crippled from being struck once upon a time by a four-horse chariot, when he was in attendance on Gaius as he was driving.

At last on the Stairs of Wailingc he was tortured for a long time and then despatched and dragged off with a hook to the Tiber."

(Suetonius, The Lives of the Caesars. The Life of Vitellius)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: