Valerius Maximus: The Collector of Roman Virtue and Vice

In Tiberius’ cautious age, Valerius Maximus turned Rome’s past into a manual of virtue. His exempla taught how to speak of courage, justice, and restraint—while his silences reveal the moral tensions of imperial power.

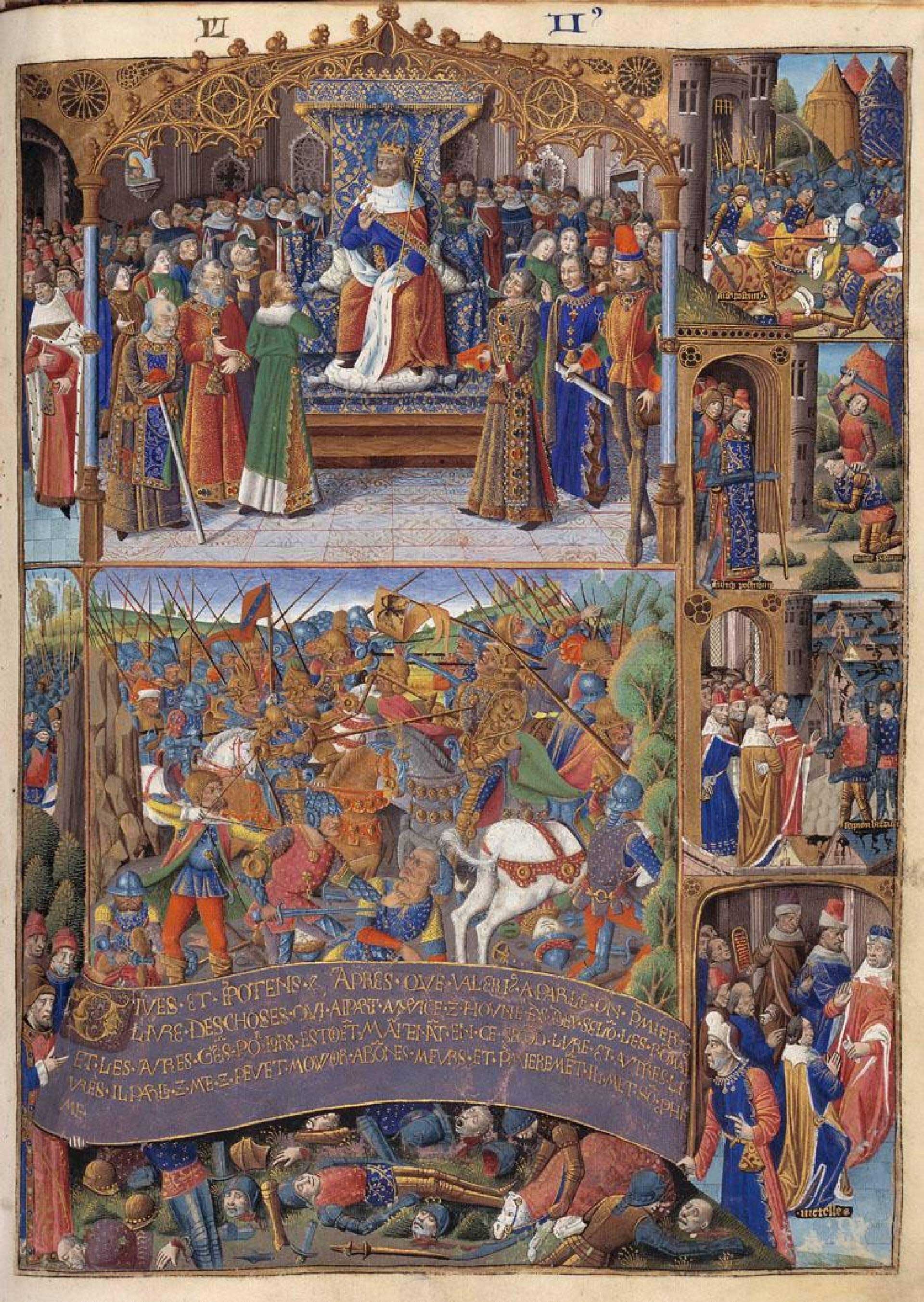

In the conservative early years of the Roman Empire, when public speech was measured and remembrance of the Republic still lingered, Valerius Maximus undertook a different kind of history. His Memorable Deeds and Sayings gathered centuries of moral examples—of courage and cowardice, loyalty and betrayal, piety and impiety—into a vast treasury of Roman experience. Written under Tiberius, it was both a manual of rhetoric and a mirror of moral order, teaching citizens how to speak of virtue while navigating a world where power had replaced freedom.

Who was Valerius Maximus?

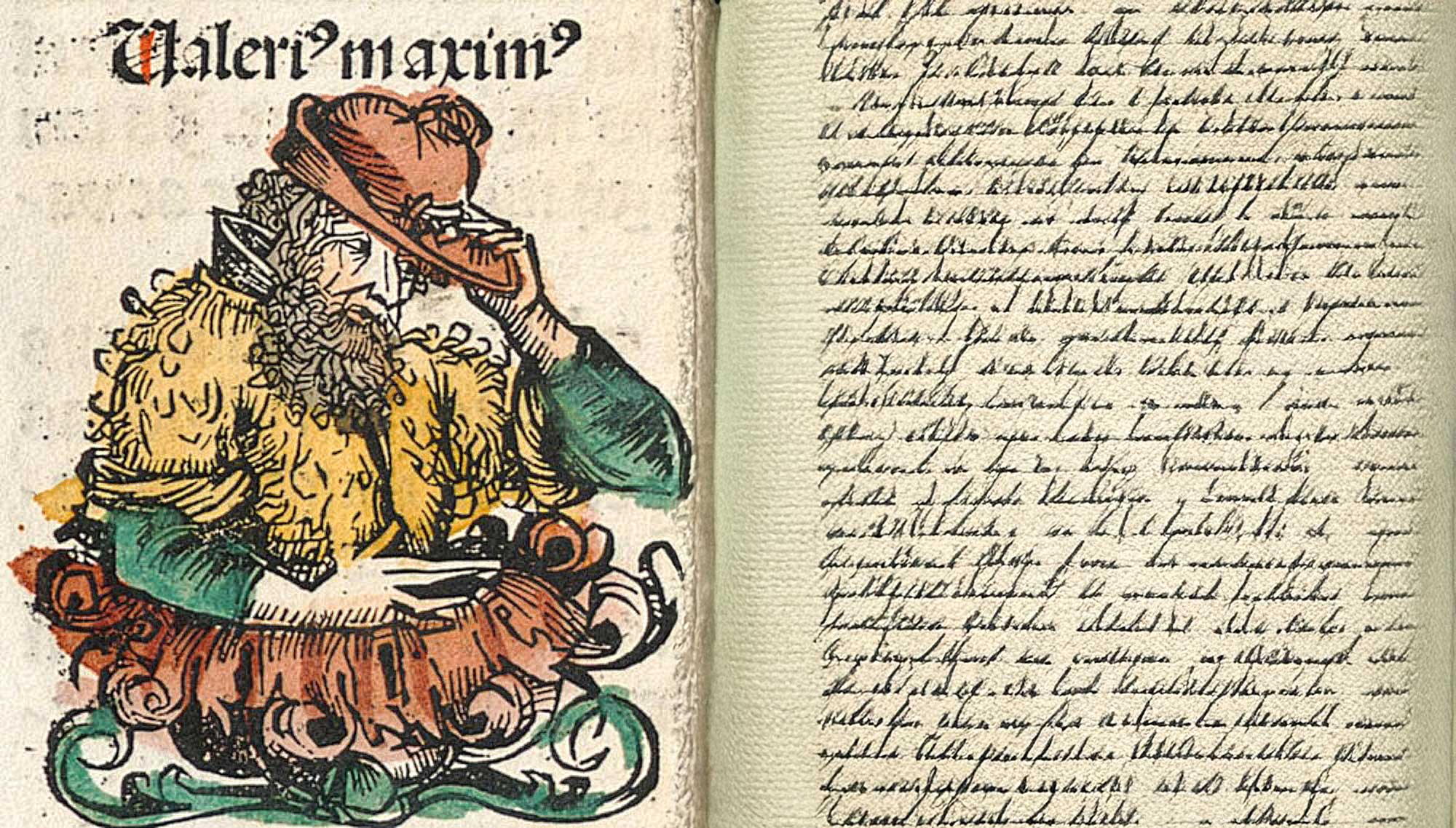

Valerius Maximus (flourished around 30 A.D.) was a Roman historian and moralist best known for his Factorum et Dictorum Memorabilium libri IX (Nine Books of Memorable Deeds and Sayings), a collection that became central to Roman education and rhetorical training.

Born to a modest family, he advanced through the patronage of Sextus Pompeius, consul in 14 A.D. and later proconsul of Asia, whom he accompanied to the East around 24 A.D. His work compiles hundreds of brief anecdotes—mainly from Roman history, though often including Greek examples—arranged by moral themes such as courage, justice, piety, and temperance.

Written in an ornate rhetorical style, his book reflects the atmosphere of Tiberius’s reign: outwardly loyal to imperial power, yet deeply rooted in Republican virtue. Drawing heavily on earlier authors like Livy and Cicero, Valerius preserved many stories otherwise lost to time. Despite its stylistic excesses and occasional inaccuracies, the work achieved immense popularity throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, remaining one of the most copied and studied texts of Latin prose.

Valerius Maximus and the Tradition of Exemplary Lives

As mentioned above, the Facta et dicta memorabilia, is a collection of “Memorable Deeds and Sayings” drawn from the lives of famous men, Roman and foreign alike. It was composed by Valerius Maximus, whose work can be placed in the middle years of Tiberius’s reign.

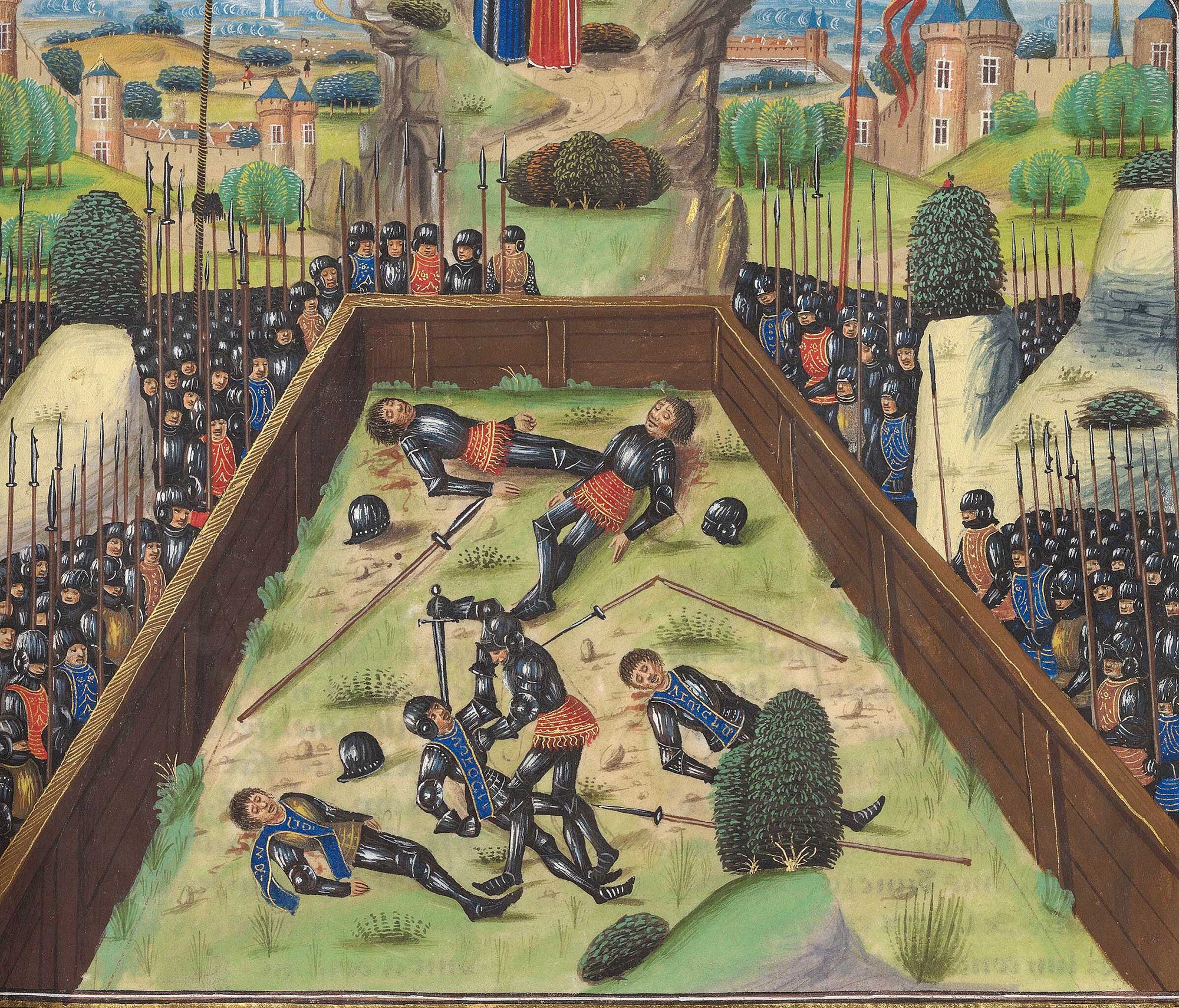

The collection offers an extensive repertoire of moral anecdotes, a reservoir of examples that later writers could employ to illustrate conduct or enliven narrative. These episodes, known as exempla in rhetorical terminology, were particularly useful to orators, historians, and biographers, who drew upon them to provide moral or emotional weight to their compositions.

Yet this practical function raises a deeper question: what purpose did Valerius himself intend for his work? His own statements, most clearly expressed in the preface but also scattered throughout the nine books, reveal an author conscious of belonging to a defined literary tradition.

The language he employs aligns his collection with the genre of the De viris illustribus—works dedicated to the deeds of illustrious men—and suggests that the Facta et dicta memorabilia may be understood as a biographical subform of this tradition. In recent scholarship, the work has often been studied for its ideological and moral significance within the context of early imperial Rome.

However, its literary dimension—its structure, vocabulary, and stylistic inheritance—offers further insight. The repeated use of verbs such as cognoscere, meaning “to become acquainted with” or “to study,” points to a tradition of moral biography in which the reader is invited not only to admire virtue but to learn from it. Valerius’s method thus reflects the influence of earlier authors, particularly Cornelius Nepos, whose De viris illustribus established the model for concise moral biography.

Although modern discussions have tended to focus on other influences, the connection between Valerius and the viri illustres tradition clarifies both the composition and purpose of his work. The Facta et dicta memorabilia stands within a continuum of Roman literature that sought to preserve moral exempla as guides to conduct. In this sense, it is more than a treasury of anecdotes—it is part of the biographical and rhetorical heritage through which Roman virtue was remembered and taught.

Remembering and Forgetting: Valerius Maximus and the Shadow of Tiberius

The work of Valerius Maximus is, at its core, an act of remembrance. Yet the author does not aim to record all things; he chooses carefully what deserves to be recalled and what must fade from memory. Beneath his collection of moral examples lies another, invisible text—a counterpart made up of the deeds and words that Valerius silently passes over. This unwritten “book of things to be forgotten” challenges modern readers to recognize that silence can be deliberate, and that omission may itself convey meaning.

To read Valerius properly is therefore to be aware of what he refuses to preserve. He excludes much that belonged to his own age, including events and people he must have known personally. With rare exceptions, his anecdotes come from earlier centuries, while the world of Tiberius remains conspicuously absent.

Yet these omissions are not neutral. The concerns and anxieties of Valerius’s own time are felt in the texture of his examples, even when they are dressed in the clothing of the past. The task for modern interpreters is to listen for these echoes—to understand what Valerius’s contemporaries would have recognized between the lines.

One way to measure what Valerius “forgets” is to set him beside Tacitus. The historian’s Annals describe the same age with a very different tone, and the contrast helps us sense what Valerius chose not to say. Tacitus’s dark vision of the reign of Tiberius can make Valerius appear complacent, even disingenuous, a writer who flatters the emperor and masks the unease of his time in the guise of moral instruction.

Yet this contrast may tell us more about the two writers’ intentions than about their integrity. Tacitus sought to expose the shadows of power; Valerius sought to show how virtue might still survive within them. To Valerius, the rule of Tiberius was a felix aetas, a blessed age governed by the optimus princeps, the best of rulers.

To Tacitus, the same reign was one of gloom and decay, its corruption radiating from the emperor himself. Reconciling these opposing visions has always been difficult, since the two authors appear to belong to different worlds of thought.

Tacitus writes as a historian of causes and consequences, tracing Rome’s moral decline through narrative; Valerius arranges anecdotes from centuries of history into a moral anthology, each story a lesson detached from chronology. Where Tacitus studies the emperor’s character, Valerius keeps him in the background, preferring to look toward the exemplary rather than the scandalous.

His silence is not ignorance but choice—a reflection of caution and of literary purpose. Valerius openly declares his reluctance to dwell on the faults of great men, writing that to reproach them for their vices would shame him. Tacitus, by contrast, finds his calling precisely in revealing such failings.

The one looks to the virtues that inspire imitation; the other to the flaws that warn against corruption. Yet both rely on the same raw material—facta et dicta, the deeds and sayings of the past—as tools for moral instruction. They differ less in substance than in tone: Valerius’s vision is optimistic, Tacitus’s profoundly tragic. Still, each believes that history’s purpose lies in ethical reflection.

Part of this divergence comes from circumstance. Valerius composed his work in the early years of Tiberius’s reign, probably completing it shortly after the fall of Sejanus in A.D. 31, one of the few datable events he mentions. Tacitus, writing long afterward, saw the full arc of that reign and its descent into tyranny.

Where Valerius experienced a stable and orderly principate, Tacitus saw its aftermath—a world of fear, suspicion, and moral exhaustion. His narrative, therefore, carries a foreboding knowledge of what Valerius could not yet foresee.

Yet the two authors meet at important intersections. Both use the deeds and words of the past to illuminate the moral fabric of Rome. Tacitus, though drawn to corruption and tragedy, still preserves acts of courage and integrity. Valerius, for his part, is capable of moral indignation, denouncing greed and cruelty with the same fervor with which he praises self-control.

Their writings, taken together, form a dialogue across time—two modes of confronting the same moral landscape, one by celebrating virtue, the other by dissecting its decay. Reading Valerius through Tacitus reveals that the Facta et dicta memorabilia is not blind to the tensions of its age. Its restraint, its very omissions, may conceal a deeper awareness of the fragility of virtue under imperial power.

Tacitus helps us recognize this undertone, while Valerius reminds us that even in an age of suspicion, memory could still serve as a vessel for hope. Each in his way teaches that the moral history of Rome was not fixed by events, but shaped by the act of remembering—and forgetting. ("Reading by Example: Valerius Maximus and the Historiography of Exempla" edited by Jeffrey Murray David Wardle)

The Purpose and Design of the Facta et dicta memorabilia

The Facta et dicta memorabilia of Valerius Maximus stands within a long tradition of Latin prose, yet its nature and purpose continue to invite debate. Before considering its later influence, it is necessary to examine the literary environment from which it emerged and the genre it occupies. Valerius himself provides frequent hints about his intentions, both in the preface and throughout his nine books.

“I have resolved to collect together the deeds and sayings of most note, and most worthy to be remembered, of the most eminent persons both among the Romans and other nations, taken out of the most approved authors, where they lie scattered so widely, that makes them hard to be known; to save the trouble of a tedious search, for those who are willing to follow their examples.

Yet I have not been over-desirous to comprehend everything.

For who in a small volume is able to set down the deeds of many ages? Or what wise man can hope to deliver the course of domestic and foreign history, which our predecessors have done in such happy styles, either with greater care, or more abounding eloquence?”

Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings, Preface {To Augustus Tiberius Caesar}

His work has often been described as a hybrid creation: a compilation of moral examples arranged as a catalogue of virtues and vices, yet shaped with the artistry of a literary composition. Written around 25–30 A.D., it draws upon earlier authors of the late Republic and early Empire, transforming their material into a new synthesis.

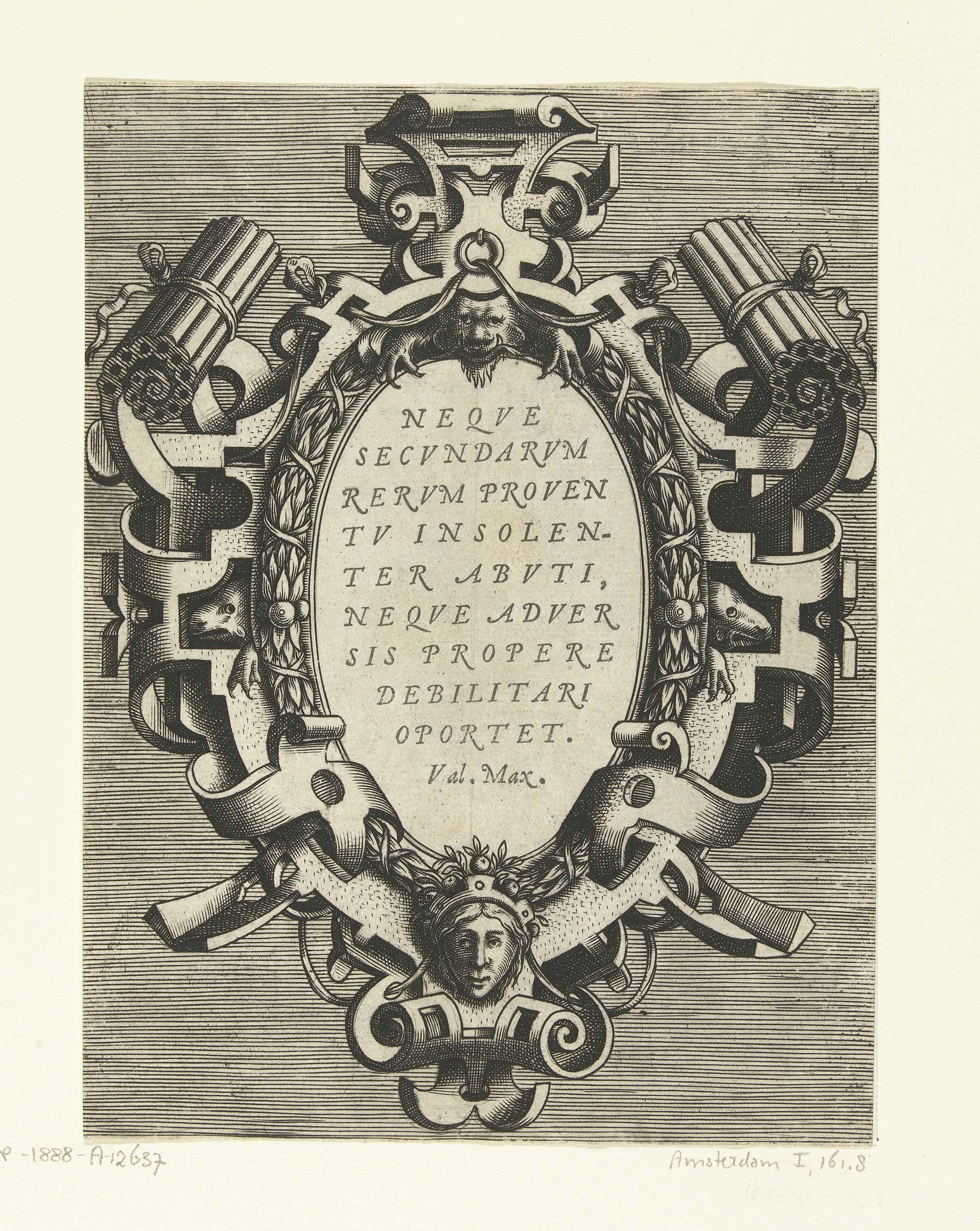

Traditionally, his work has been regarded as a rhetorical manual or handbook for moral instruction, a resource from which orators could extract examples without the labor of extended research. This view stems from Valerius’s own statement that he wrote ut documenta sumere volentibus longae inquisitionis labor absit—

“so that those who wish to take examples may be spared the toil of long inquiry.”

The collection’s wealth of episodes and moral contrasts supports this idea, and its arrangement allows readers to locate suitable examples for speeches, histories, or moral essays. Yet modern scholarship increasingly recognizes the work’s literary sophistication: its deliberate structure, narrative artistry, and rhetorical embellishment reveal a composition far removed from a mere reference book.

It possesses the refinement of a finished literary work. It opens with a dedicatory preface to the emperor, includes acclamations, apostrophes, personifications, and artfully inserted quotations, and employs stylistic devices such as litotes, chiasmus, and direct speech.

“Therefore, Caesar, your country's only safety, I invoke you at the beginning of my undertaking, whom the consent of gods and men has ordained the great commander both of sea and land; by whose divine providence those virtues, of which I am to discourse, are most favourably cherished, and vices most severely punished.

For if the ancient orators did well to begin from omnipotent Jove, if the most excellent poets did always call some particular deity to assist them; much the rather does my little work fly to your protection.

For other gods we adore only in opinion, you we behold equal to your father's and your grandfather's stars in brightness, whose resplendent lustres have added not a little to the ceremonies of our religion.

Others we receive for gods, Caesars we make such. And because it is my intention to begin with the worship of the gods, I shall discourse briefly of its nature.”

Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings, Preface {To Augustus Tiberius Caesar}

The vividness of its narrative, sustained by metaphors of sight and vision (energeia or evidentia), points to an aesthetic ambition comparable to that of Cicero’s De oratore. Rather than offering raw material for rhetorical practice, Valerius presents a model of composition in action—an embodiment of how persuasion might be achieved through moral example.

His declaration of modest intent, therefore, should not be taken at face value. The phrase ut documenta sumere volentibus… belongs to a familiar literary topos of humility. Similar expressions appear in earlier writers: Caesar’s commentaries, praised for providing material for others to shape; Suetonius’s and Cicero’s remarks on the gathering of facts for historical writing; and Pliny’s letters, offering unpolished details for Tacitus to refine.

Valerius’s formulation echoes these conventions. By appearing self-effacing, he diverts attention from the scale of his own project—a work that aims not merely to compile examples but to create an encyclopaedia of Roman morality.

Seen in this light, the Facta et dicta memorabilia is both a practical sourcebook and an original literary achievement. It provides moral instruction through example while demonstrating the rhetorical artistry that turns moral discourse into literature. Valerius transforms the ancient practice of collecting exempla into something larger: a structured moral universe, where virtue and vice are not only remembered but rendered visible through language.

Valerius Maximus and His Legacy in the Later Empire

The influence of his work extended well beyond Valerius Maximus’s own generation. His collection of moral examples began to circulate almost immediately after its completion, finding use among authors concerned with ethical and rhetorical instruction.

Early readers such as Seneca and Quintilian, each in their respective philosophical and educational writings, appear to have drawn on his treasury of exempla as a source of moral illustration. In the second century, Aulus Gellius’s Noctes Atticae often employed the same anecdotes known from Valerius, suggesting that his collection served at least as a subsidiary reference.

The biographical tradition that had gained momentum under Suetonius at the start of the second century continued to flourish in subsequent generations. Writers such as Marius Maximus, whose imperial biographies partly survive within the Historia Augusta of the late fourth century, developed the same interest in moral portraiture that characterized Valerius’s method.

Beyond biography, traces of his influence can also be detected in moral treatises and historical writing, where his arrangement of virtues and vices offered a model for later authors seeking moral clarity within narrative. By the late Empire, Valerius’s presence was deeply embedded in the Latin literary tradition. Two compendia from Late Antiquity confirm that his work remained widely known, and the extraordinary number of surviving medieval manuscripts attests to its enduring popularity.

Yet identifying direct borrowings is difficult. Because Valerius himself relied heavily on earlier authorities such as Cicero and Livy, later writers often drew upon his material without naming him, blurring the distinction between his work and that of his predecessors. The problem is compounded by the likelihood that intermediate authors, including Seneca and Quintilian, transmitted his examples indirectly to later centuries.

Even so, numerous parallels suggest that his moral vocabulary and repertoire of anecdotes continued to shape Roman thought. Lactantius, in his critique of pagan religion, employed many mythological exempla familiar from Valerius, while Ammianus Marcellinus, writing in the tradition of Livy and Tacitus, shared Valerius’s preference for historical rather than mythological examples.

Ammianus does not name him, yet his harmonization of republican and imperial virtues echoes the spirit of the Facta et dicta memorabilia. It is plausible that he made use of Valerius, particularly in the middle books of his Res Gestae covering the years up to Julian’s reign.

Traces of Valerius are also discernible in later rhetorical literature. The Panegyrici Latini, the great corpus of imperial orations composed between 289 and 389 A.D., reveal the influence of his moral style and narrative structure. These orators, steeped in the classical tradition, likely viewed Valerius as part of their rhetorical heritage.

Modern studies, such as the analysis of Nazarius’s speech of 321 A.D., have noted verbal and stylistic affinities that point to him as a model of refined Latin prose. Far from being a marginal compiler, Valerius Maximus emerged as one of the enduring custodians of Roman language and ethics.

His collection, valued not only for its moral instruction but also for its elegance of expression, may well have been regarded as a standard of classical Latin equal to that of Caesar and Cicero. In the learned circles of Late Antiquity, he remained both a moral guide and a stylistic exemplar—proof that the memory of Rome’s virtues, once set in his pages, continued to instruct long after the Republic had faded. (Valerius Maximus’ Facta et dicta memorabilia and the Roman Biographical Tradition, by Diederik Burgersdijk)

Valerius Maximus did not write history to settle accounts but to train judgment. By arranging Rome’s deeds and sayings into a living gallery of virtue and vice—and by choosing when to be silent—he taught readers how to remember well. That discipline of memory, tested under empire and preserved through Late Antiquity, kept Rome’s moral language alive long after the Republic was gone.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: