Valerian: The Only Roman Emperor Who Was Captured Alive by an Enemy

Valerian’s capture by Shapur I in 260 CE was Rome’s most humiliating defeat—its emperor turned into a Persian trophy. His fate, ambiguous and unforgettable, inspired centuries of reinterpretation, from Christian polemic to Byzantine invective and Persian pride.

He was the only Roman emperor ever taken alive by a foreign enemy. Valerian’s reign, beginning in 253 CE, unfolded during one of the empire’s darkest hours—a time of invasions, plague, and internal unrest. His capture by the Persian king Shapur I in 260 was more than a personal humiliation; it was a blow to Roman prestige that shook the foundations of imperial power and became a symbol of the empire’s vulnerability in the age of crisis.

Valerian in Chains: Rome’s Emperor as a Trophy of Defeat

The capture of Emperor Valerian (r. 253–260) by the Sasanian Persians in Syria stands as one of the most infamous defeats in Roman history. Zosimus described it as:

“the greatest shame to the name of the Romans for future generations”

While other Roman commanders had lost battles, armies, and even their lives in the East, Valerian’s survival as a living trophy for Persia was without precedent. Roman political culture placed supreme value on martial courage, and emperors followed Augustus’ example by framing their role through displays of virtus. The epithet “Unconquered” (invictus) had by then entered official imperial usage, moving from literature and provincial inscriptions into the language of Roman power itself.

Against this backdrop, Valerian’s surrender of his freedom to a foreign enemy in 260 represented a failure of unparalleled magnitude, overshadowing the deaths of emperors in both foreign wars and civil strife during the same century. He became, in effect, a celebrity of defeat, whose fate allowed later writers to employ his story well beyond the event itself.

Yet, despite its importance, Valerian’s fall has often been absorbed into the broad category of the “third-century crisis.” Modern historians usually reduce it to a passing entry in surveys of imperial disasters or as a prelude in accounts of his son Gallienus (r. 260–268). Placed alongside Decius’ death against the Goths in 251, it marks the lowest ebb of Roman foreign policy and frontier security.

When scholars have sought to reconstruct the disaster in detail, they have typically focused on chronology, the military context, or the trustworthiness of ancient testimony—debating whether Valerian was humiliated in captivity, whether his body was desecrated after death, and whether he was an incompetent general or a principled Roman aristocrat. These approaches rest on privileging some sources as more reliable than others to piece together the most accurate version of events.

But what if the focus shifted from reconstructing “what happened” to understanding how different narratives sought to explain an unprecedented disaster? From Persian inscriptions to late-antique fictional biographies and Christian historiography, Valerian became an irresistible figure for reinterpretation. His capture served as fertile ground for diverse traditions, confirming Gibbon’s later judgment that:

“the Pagan writers lament, the Christian insult, the misfortunes of Valerian.”

The Earliest Memory of Captivity: Valerian in Shapur’s Res Gestae

The first surviving record of Valerian’s capture appears in the Res Gestae Divi Saporis (Accomplishments of the Divine Shapur), a trilingual inscription at Naqsh-i Rustam in Iran that celebrated the deeds of Shapur I in Middle Persian, Parthian, and Greek. Although its precise date is uncertain, the text was almost certainly composed between 260 and 262, when the triumph was fresh and Valerian likely still alive, but before Shapur’s campaign against Palmyrene forces.

Roman historians usually follow Mikhail Rostovtzeff’s Latin name for the text, but specialists on Persia refer to it as the Shāpūr–Ka‛ba-ye Zardošt or ŠKZ. In recounting the event, the scribe drew on Parthian traditions of diplomacy with Rome, offering detailed yet inaccurate information about the Roman army.

The inscription treats Rome as a formidable enemy, presenting Valerian as nearly equal to Shapur himself, “king of kings.” Shapur also portrayed his campaigns not as divinely ordained conquests but as justified responses to Roman aggression. The ŠKZ narrates the climax of his third campaign in clear terms:

“And on the far side of Carrhae and Edessa [now Harran and Şanlıurfa in Turkey] a great battle occurred between us and the Caesar Valerian, and we took the Caesar Valerian prisoner with our own hands as well as the other leaders of the army, the praetorian prefect and the senators and the officers, all these we took in hand and deported to Persis.”

ŠKZ §22, lines 24–26

The phrase “took in hand” (ἐν χερσὶν ἐκρατήσαμεν) echoes the iconography of Shapur seizing Valerian by the hand in Persian reliefs and in a cameo now in Paris. In this account, Valerian is presented not as an emperor humiliated but as part of the captured spoils, alongside his praetorian prefect and high-ranking officers.

Since the memory of victory was fresh, the ŠKZ required no further narrative about his fate as a deportee in Persia. Epigraphy and reliefs alike made the mere fact of capture the ultimate proof of Shapur’s power.

Yet the inscription’s silences may hint at a hidden Roman achievement. While Shapur claims victory outside Carrhae and Edessa, those cities do not appear on his list of conquests. Some later sources suggest why: Peter the Patrician reports that the Persians bribed the Edessa garrison with seized “Syrian money” to allow a safe passage. This suggests Roman control persisted in at least one city, even if it was secured by corruption rather than valor.

Zosimus, writing in the sixth century, went further by insisting that Valerian’s defeat had not allowed Persia to seize Rome’s eastern provinces. In his New History, Valerian remains a failed emperor, but not the worst: that dishonor was reserved for the Christian Jovian, who surrendered irrecoverable territory. In this way, Zosimus diminished Valerian’s disgrace by placing it within a larger arc of eastern defeats.

A different lens comes from the Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle, which offers a Syrian perspective from the 260s. The Sibylline Oracles, a composite collection mixing Greco-Roman myth with Jewish and Christian ideas, presented prophecy in familiar forms to persuade readers of their authenticity. Here Valerian’s defeat appears in allegory:

“The high-necked bull digging the earth with his hoofs and rousing the dust on his double horns will do much harm to the dark-hued serpent cutting a furrow with its scales; then [the bull] will be destroyed.”

The bull represents Valerian, who fought fiercely but was ultimately annihilated by the Persian serpent. The oracle passes over the detail of capture, emphasizing instead his obstinate struggle and utter downfall.

In this prophetic vision, Roman calamity sets the stage for renewed local resistance by leaders such as Uranius Antoninus of Emesa and Odaenathus of Palmyra. Thus, in the Syrian imagination, Valerian’s defeat did not carry the weight of an imperial crisis; instead, it heralded the rise of saviors who would eventually strike back at Persia.

Educated Folklore: Valerian’s Defeat in the Historia Augusta

A century after Valerian’s capture, Roman imagination reshaped the disaster through the Historia Augusta, a compilation of imperial biographies notorious for blending invention with history. Although unreliable for reconstructing events of the third century, it offers a glimpse into how later Romans remembered the past as a form of educated folklore.

Much of the Life of Valerian is lost, and what remains is largely fabricated correspondence. From the vantage point of the late fourth century, the author claimed that Shapur broadcast his triumph across the East, receiving four kinds of responses.

One group—including the Bactrians, Iberians, Albanians, and Tauroscythians—allegedly rejected Shapur’s letters and pledged their support to Rome in freeing Valerian. This list, spanning from border kingdoms like Iberia and Albania to distant Bactria and the anciently described Tauroscythians, displays both geographic erudition and the assertion of Rome’s friends on every frontier.

It also reflects the strategic importance of the Caucasus—the “Mountain Arena” of Roman–Persian rivalry—as described by Elizabeth Fowden. (Elizabeth Key Fowden is a noted historian specializing in the cultural, religious, and political interactions between Rome and Persia during Late Antiquity and the early Islamic period.)

Its control influenced the outcome of major wars between the two powers.

Fowden herself uses the term “Barbarian Plain” to designate the Syrian steppe region centered around Rusafa, a frontier zone critically situated between Rome and Iran.

This area is depicted as ethnically diverse and culturally dynamic, with its local religious and martial identities shaped by proximity to both imperial spheres.

Thus, “Mountain Arena” refers to the wider Caucasus frontier, while “Barbarian Plain” refers more specifically to the Syrian frontier where Fowden concentrates her study.

The Armenian king’s supposed reply offers a prophetic caution. He admitted both Shapur’s success and Armenia’s role in Valerian’s downfall, but warned:

“therefore, you have captured one old man but have made all the nations of the world extremely hostile to you”.

Armenia’s position between Rome and Persia made any war ruinous for its people, an observation well-suited to the fourth-century reality of a divided Armenia caught between empires.

Another letter, attributed to a Cadusian ruler north of Media, urged Shapur to restore Valerian, arguing that a magnanimous gesture would bring him greater honor. It called Valerian “leader of leaders” (princeps principum), elevating the captive emperor to a rank almost equal with the Persian “king of kings.” This appeal also invoked a recurring Roman trope:

“Romans are never more troublesome than when they are conquered” (2.2).

As Livy and Polybius had noted in earlier defeats, disaster often sharpened Roman resolve. In this spirit, the author pointed to Galerius as the one destined to avenge Valerian and restore Roman honor (Life of Carinus 18.3).

Other letters reinforced this theme of resilience. One unnamed correspondent argued that Rome’s past enemies—the Gauls, Carthaginians, and Mithridates of Pontus—had all eventually fallen under Roman power, warning Shapur that Valerian’s capture might lead to Persia’s own downfall.

“Rome, through Fate or its own virtus, is supremely powerful,”

the letter declared, insisting that the emperor had been seized only “by trickery” (fraude). The Historia Augusta also claimed Valerian was “overcome by a kind of fated inevitability”, but sought to preserve his dignity as a great man supported by the Senate. Thus, even amid fabrications, the work framed Rome as dangerous even without its emperor, Fortune as fickle, and Valerian as worthy of respect despite misfortune.

The account also turned to Valerian’s son. When most Romans grieved, Gallienus was said to have celebrated, excusing himself by claiming his father had been captured through “eagerness for virtus”. Another explanation was that Gallienus rejoiced in freedom from his father’s famous gravitas. Philosophical asides and dark humor followed: Gallienus reportedly adapted the saying:

“I knew that my father was mortal,”

and during one procession, jesters searched among Persian captives “for the emperor’s father”. Their fate, being burned alive by Gallienus’ orders, added cruelty to his portrait. The narrative closed with a reminder that Valerian never returned home, not even in death. The so-called tomb of Valerian near Milan belonged instead to his son of the same name, later marked “Valerianus imperator” by Claudius II.

Taken together, the Historia Augusta reimagined Valerian’s defeat in ways that honored his memory, foreshadowed Roman revenge, and contrasted his gravitas with his son’s frivolity. In doing so, it suited a fourth-century world once again locked in eastern wars, where the desire for a new optimus princeps in the mold of Trajan or Marcus Aurelius shaped the storytelling of Rome’s past.

Julian and the Silence on Valerian’s Chains

A century after Valerian’s humiliation, Emperor Julian (r. 361–363) marched east against Shapur II, the great-grandson of Valerian’s captor. His army retraced the battlefields of earlier Roman–Persian wars, but Valerian’s name is strikingly absent from contemporary accounts. Ammianus Marcellinus, who may himself have served in Julian’s Persian campaign, recalls reminders of other disasters but not Valerian.

He identifies Carrhae only as:

“notable for the calamity of the Crassi and the Roman army,”

Amm. Marc. 23.3.1

referring to Crassus’ fatal defeat in 53 BCE. Near Dura, Julian made offerings at the tomb of the deified Gordian III. Gordian’s role in Roman–Persian history was contested: Roman tradition hailed his victory over Shapur I, while the Persian ŠKZ listed him among the king’s conquests. In addressing his troops after crossing the Euphrates, Julian invoked victorious emperors such as Trajan, Lucius Verus, and Septimius Severus, lamenting only in general terms:

“the unavenged shades of our butchered armies, the immensity of our losses … urge us on to the task we have undertaken, for all of us are united in our vows to remedy the past”

The omission of Valerian suggests Julian’s unwillingness to acknowledge this catastrophic precedent.

Yet Julian was not ignorant of Valerian’s fate. In his satirical Caesars, where a banquet of emperors is staged, “the father of Gallienus” appears with the emblems of captivity (Julian, Caes. 313B). There the jester Silenus mocks him with a line from Euripides’ Phoenician Women:

“Who is the white-plumed man who stands in front to command the army?”

Without granting Valerian or Gallienus a word, Zeus commands them to leave the gathering. Julian’s silence thus reflects contempt, for the disgrace of Valerian’s chains was intolerable to a ruler who sought to emulate Alexander the Great. Indeed, in the same dialogue, Alexander derides Julius Caesar by stressing the futility of three centuries of Roman wars against Persia, which had never secured a province beyond the Tigris. In this reckoning, Valerian, though unnamed, embodied the futility that Julian wished to rise above.

After Julian’s own Persian expedition ended in disaster and cost him his life, his critics used the memory he had suppressed. Gregory of Nazianzus invoked Valerian not as a persecutor of Christians, but as a cautionary parallel: another emperor who advanced too boldly into Persia and paid with ruin. Thus, Valerian re-entered the narrative of Julian’s reign only when his enemies employed the shame of the past to underscore the emperor’s defeat.

From Persecutor to Trophy: Christian Memories of Valerian’s Captivity

Unlike Julian, Christian writers insisted on remembering Valerian—but as the persecutor of their faith whose capture was merely the beginning of his punishment. The shock of his unprecedented “disappearance” demanded explanation, and Lactantius offered one in the early fourth century. In On the Deaths of the Persecutors, he interpreted Valerian’s humiliation as part of God’s plan, calling it a:

“new and singular form of punishment”

According to him, the emperor was stripped of both imperium and libertas as divine retribution for his crimes against Christians. Unlike other persecuting emperors who met disgraceful deaths and damnatio memoriae, Valerian lived on as a footstool for Shapur, a reversal of Roman art that had long shown Persians submitting at Roman feet.

For Lactantius, this ongoing degradation surpassed Decius’ fate, whose corpse became “food for wild beasts and birds”. He even drew from the Psalms: “till I make your enemies your footstool,” linking Valerian’s abasement to Christ’s cosmic dominion (Div. inst. 4.12.17). Such imagery was so powerful that Lactantius claimed Persians despised all Romans because of the captive emperor.

Gallienus’ failure to ransom his father was, in his view, not a personal flaw but a further sign of God’s wrath. The story continued after Valerian’s death, when his body was supposedly flayed and dyed red as a grotesque warning—whether or not Shapur actually preserved him in this way.

Even Diocletian, Lactantius claims, was restrained by the “precedent of Valerian” (exemplum Valeriani) from leading an army against Persia himself. Thus, in Christian polemic, Valerian’s fate became proof that Rome’s victories were fleeting before divine justice.

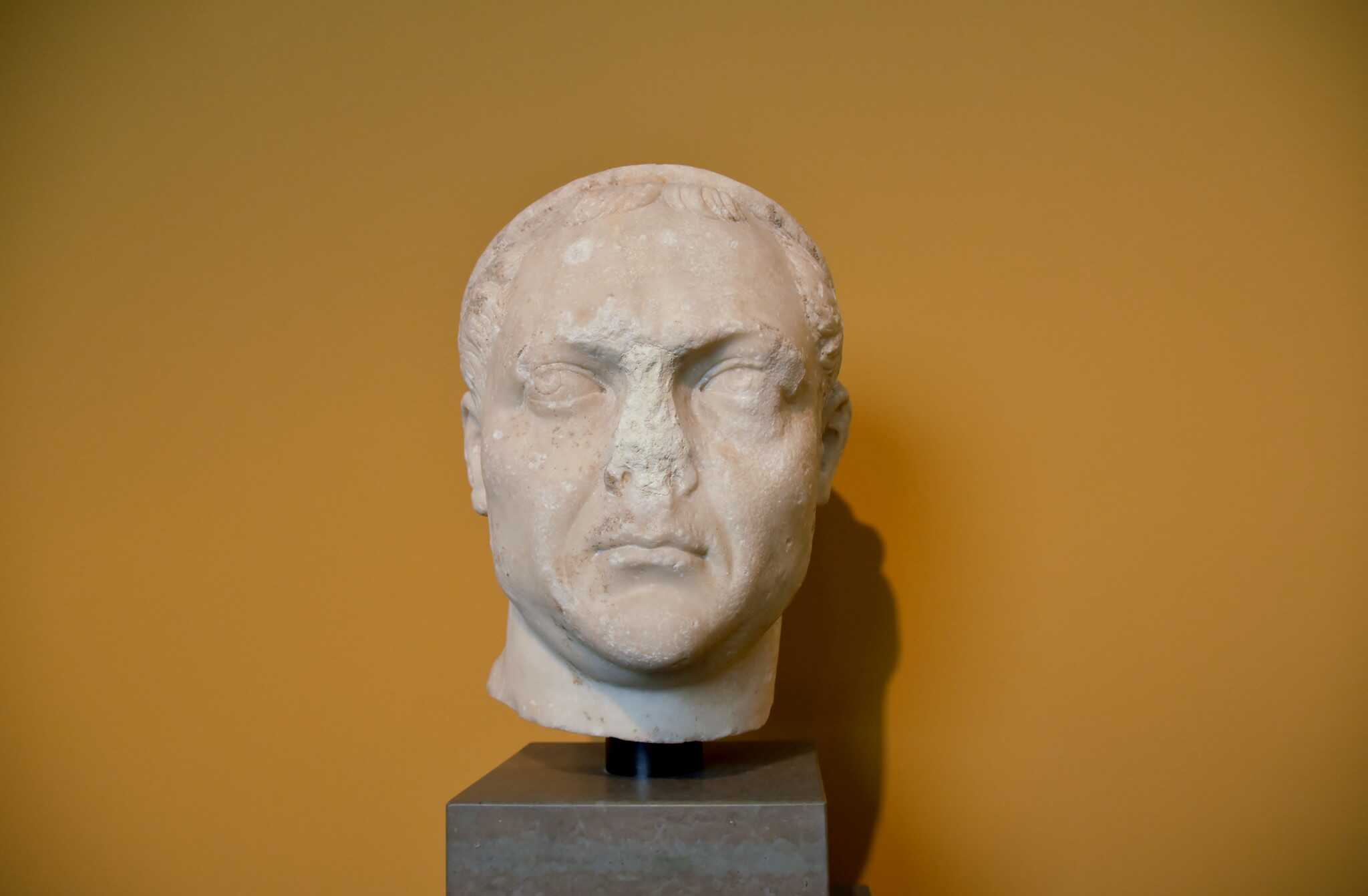

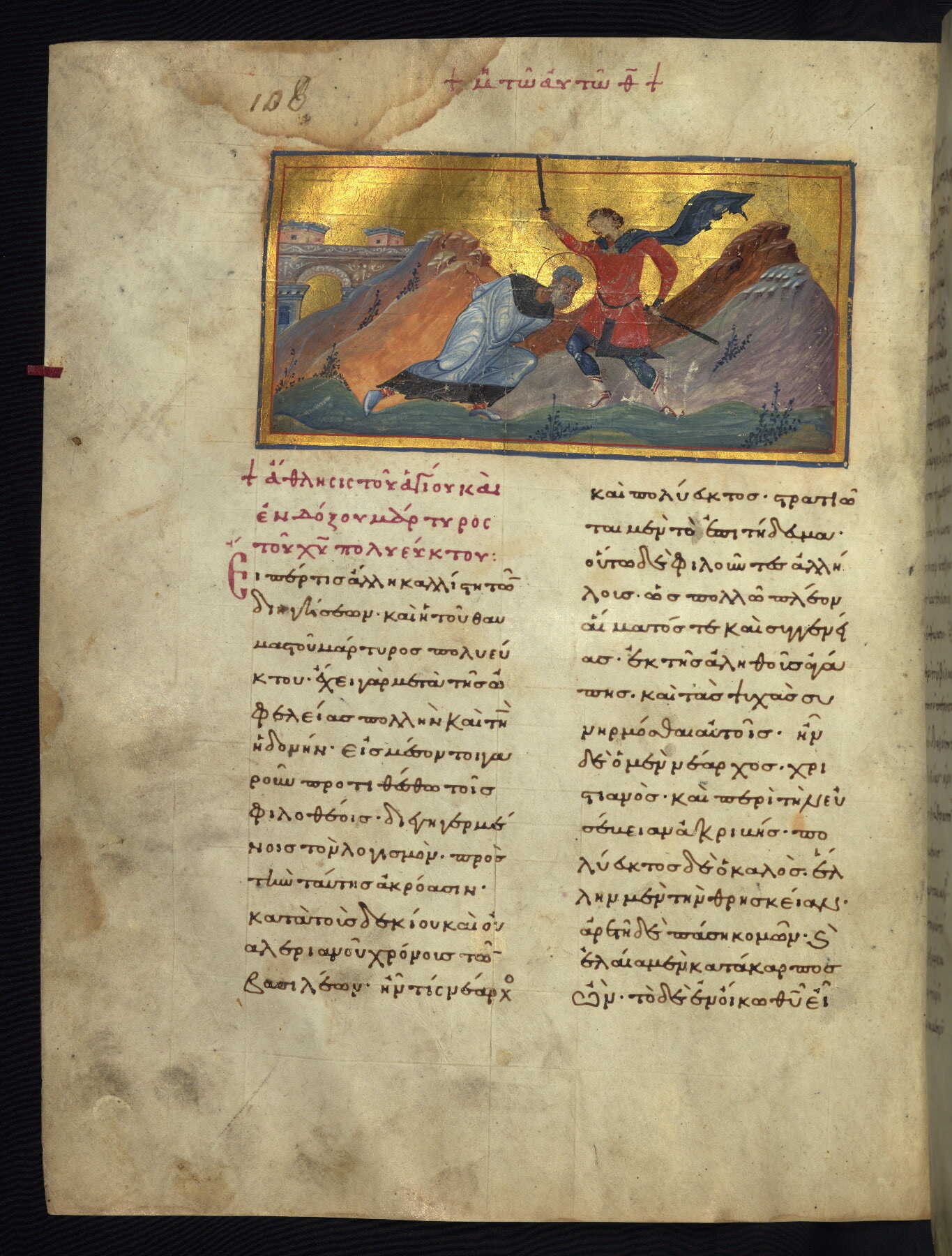

Image #1: Page from an Imperial Menologion, depicting a saint being beheaded here (Polyeuctus), a Roman army officer martyred at Melitene (Asia Minor) under Emperor Valerian in 259. Credits: Walters Art Museum Illuminated Manuscripts, Public domain. Image #2: The martyrdom of Saint Cyprian, who was executed under Emperor Valerian. Credits: Lawrence OP, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Eusebius of Caesarea carried this interpretation further. He cited Dionysius of Alexandria, who saw in the Apocalypse a prophecy that the “first beast” referred to Valerian, persecutor of Christians. Dionysius predicted he would rule for three-and-a-half years before God stripped him of power, and his disgrace fulfilled Isaiah’s words:

“These have chosen their own ways and their own abominations; their soul delighted in them. I will choose their delusions, and for their sins I will repay them”

Valerian’s captivity, therefore, was divine punishment realized. When Constantine later celebrated his own victories, he took up this legacy. In his Oration to the Assembly of the Saints, Constantine singled out Valerian:

“caught and led as a prisoner in bonds with your very purple … finally, flayed and pickled at the behest of Shapur the king of the Persians, you were set up as an eternal trophy of your own misfortune!”

Here, Valerian became not a Persian warning to Romans, but a Roman reminder of God’s justice. Even in diplomacy, Constantine used the precedent. In a letter to Shapur II, preserved in Eusebius’ Life of Constantine, he referred to Valerian obliquely as:

“that one, who was driven from these [Roman] parts by divine wrath as by a thunderbolt … left in yours, where he caused the victory on your side to be very famous because of the shame he suffered”

By reframing Valerian’s humiliation as God’s work, Constantine warned Shapur to treat Persian Christians well—or risk divine punishment himself. Later writers, however, were not satisfied. Orosius, writing after the sack of Rome in 410, insisted that Valerian’s punishment was too small a price for the blood of the martyrs.

“The incarceration of one impious man, albeit that it was forever and of a particularly vile kind, did not compensate … for the torture of so many thousands of the saints”

Historiarum, 7.22.4.

He repeated Lactantius’ image of Valerian as Shapur’s footstool but argued that God had punished the whole empire with barbarian invasions, civil wars, and torrents of blood. Valerian’s captivity was thus only one episode in a divine cycle of vengeance, insufficient to balance the weight of Christian suffering.

Image #1: A fresco depicting Saint Lawrence, in the presence of Emperor Valerian, is being beaten prior to his execution. Credits: Jim Forest, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Image #2: Saint Lawrence was arrested under the Emperor Valerian in 258, laid upon a gridiron and slowly roasted to death, while he rejoiced in his awful martyrdom and died praying for the conversion of the city of Rome. Credits: Thomas Hawk, CC BY-NC 2.0. Image #3: A mosaic of Saint Lawrence by Tessa Hunkin inside Westminster Cathedral, he holds the martyr's palm, and the purse which he was entrusted with as the almoner of the Roman Church, in the background is the gridiron on which he was executed. Credits: Lawrence OP, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Valerian’s Authority in Captivity: Peter the Patrician’s Perspective

Rather than emphasize themes of shame or divine retribution, the sixth-century historian Peter the Patrician approached Valerian’s disaster through the lens of a bureaucrat in Constantinople. He highlighted two diplomatic episodes—one contemporary to the emperor’s captivity and another tied to the Treaty of 298—that reveal how later Romans reflected on loyalty, authority, and imperial image.

The first story concerns Macrinus, comes thesaurorum (count of the treasuries) at Samosata, who received a summons from Valerian in captivity. Shapur had allowed the official Cledonius, captured with Valerian, to deliver the request. But Macrinus refused to obey, declaring that no rational man would choose slavery over freedom and dismissing both Shapur and Valerian:

“one [Shapur] is an enemy, the other [Valerian] neither his own master nor ours.”

Cledonius, however, interpreted the matter differently, insisting that his emperor still merited loyalty, and he returned to captivity beside him. Peter, trained in law, was drawn to the deeper issue—whether Valerian still retained authority as a prisoner of war.

Macrinus framed his refusal in philosophical and legal terms, while Cledonius acted from personal devotion regardless of consequence. For Peter’s sixth-century audience, the account underscored enduring questions of obedience and duty within the imperial bureaucracy, framed with careful precision in his Greek translations of their official titles.

Peter also recalled Valerian’s disgrace in the context of later Roman diplomacy with Persia. He noted that negotiations following Galerius’ victory in 298 included a Persian appeal to the “mutability of human affairs.” Apharbān, envoy of King Narseh, thanked Galerius for his treatment of the captured Persian royal family but added that reminder of changing fortune. The words enraged Galerius, who rebuked the Persians for recalling Valerian’s fate:

“after you had tricked [Valerian] with deceptions, held him to extreme old age and did not spare him a dishonorable end, then, by some abominable art, having preserved his skin, perpetrated an immortal outrage on a mortal body.”

Despite such anger, Peter emphasizes that Galerius chose generosity, not vengeance. He attributes this restraint not to human fate but to Roman principle, citing Virgil’s maxim:

“to spare the subject and subdue the proud”

Virgil, Aeneid, 6.853

Thus, where Shapur had sought to teach Rome a lesson with Valerian’s capture, Peter recasts Galerius as teaching the Persians what it meant to act with Roman virtue.

Image #1: Bas-relief from the 2nd century AD in the Tang-e Chowgan gorge by Bishapur, damaged by water flowing from an aqueduct. Image #2: Detail from the carving, where Valerian as a slave in Bishapur, depicted here as aiding Shapur onto his horse. Credits: youngrobv, CC BY-NC 2.0

Shapur the Cruel: Byzantine Echoes of Valerian’s Defeat

Romans not only affirmed their superiority in the face of Valerian’s humiliation but also used the story to vilify their Persian adversaries, who remained formidable foes into the sixth century. Whereas Peter the Patrician emphasized Shapur’s arrogance, Agathias painted a darker portrait of the king:

“a monster of wickedness and injustice … who set a dreadful precedent of vindictive cruelty and obscene brutality,”

Agathias, The Histories, 4.24.3

by flaying Valerian alive. Agathias added that after the emperor’s death, Shapur unleashed plunder without restraint, pushing his campaigns from Syria into Cappadocia. For Agathias, writing in the reign of Justin II (565–574), the story resonated with his own age, when Rome again clashed with Persia and suffered defeats so severe that one may have driven the emperor himself into madness.

Agathias’ disgust for Persia is further illustrated through a tale of Roman philosophers who sought refuge there, imagining it to be a haven for non-Christians. Yet they quickly fled, deciding that:

“despite the Persian king’s affection for them … they felt that merely to set foot on Roman territory, even if it meant instant death, was preferable to a life of distinction in Persia”

Agathias, The Histories, 4.24.3

By the twelfth century, John Zonaras in his Epitome of Histories expanded on Agathias’ themes, stressing how Shapur’s cruelty deepened after Valerian’s capture and how the Persian king grew presumptuous in claiming mastery over the world. Among the most gruesome episodes is the report that Shapur, retreating toward Persia, crossed a ravine by filling it with the corpses of his Roman captives.

Once the Christian version of Valerian’s humiliation had gained wide circulation, Byzantine historians added another layer: the capture of Valerian not only disgraced Rome but also corrupted Persia. Shapur’s triumph became proof of the degenerating effect of excessive victory, a theme that reinforced Byzantine moralizing about their eastern enemy across the centuries.

Al-Tabari’s Shapur: Valerian the Builder in Captivity

In the tenth century, the historian Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari recorded a Sasanian perspective on Valerian’s fate, drawing from the seventh-century Khvadhaynamagh (Book of Kings) tradition. His History of the Prophets and Kings celebrates Shapur’s triumph not only in war but in the emperor’s long captivity.

According to this account, after Valerian’s defeat—misplaced here at Antioch—he was resettled at Junday Sābūr (Gundeshapur). There, the Persian king forced “al-Riyānūs” (Valerianus) to oversee the building of a dam at Tustar (Shushtar), with Roman prisoners as the workforce. Valerian:

“held Shapur to a promise to free him once the dam was completed. It is said that Shapur took from al-Riyānūs a great financial indemnity, and set him free after cutting off his nose; others, however, say that Shapur killed him.”

The error of placing the defeat at Antioch nevertheless ties symbolically to Gundeshapur, whose foundation name Beh-az-Andew-i-Shapur (“better than Antioch of Shapur”) commemorated the Persian king’s rivalry with Rome. In this retelling, Shapur outshines his enemies not only in battle but also in urban achievement.

The Tustar dam and bridge become evidence of his skill as a ruler who transformed captives into useful labor. In some strands of the story, Shapur even appears as a fair master, though the mutilation of Valerian—his nose cut off before release—may reflect Byzantine or Arab traditions of corporal punishment rather than Persian practice.

Thus, centuries after the event, Persian tradition recast Valerian’s capture in a way that honored Shapur. The emperor who had once been Rome’s supreme ruler became in memory a prisoner-builder, a symbol of Persian superiority in both conquest and construction, and—at least in one version—a captive granted a partially favorable end.

Image #1: Where the Karun River passes through the Shushtar watermills in Iran, a construction overseen by the captive Emperor Valerian. Image #2: A small Roman bridge managing the flow of the Karun River for the Shushtar watermills. Image #3: ‘Ceasar's bridge' that also functioned as a dam, is the easternmost construction of the Roman Empire, although it was built by the Roman Emperor Valerian and the remains of his army, as slaves. Credits: youngrobv, CC BY-NC 2.0

The Unfinished Fate of Valerian: An Emperor Reimagined Across Centuries

The scale of Valerian’s defeat generated extensive commentary, and when we move beyond the events of his reign, the sheer variety of references to his infamy is striking. Early responses in Persia and Syria concentrated on the disgrace of the capture itself, but the uncertainty surrounding his fate soon opened the way for reinterpretation.

As aforementioned, the Historia Augusta reshaped Valerian for a fourth-century audience, turning disaster into a story that upheld imperial virtus and stability. Julian, by contrast, sought to erase him entirely from the memory of Rome’s Persian wars, though Christian authors swiftly restored him to prominence.

For them, Valerian’s persecution of the Church explained his ruin: Lactantius highlighted the grotesque details of humiliation to critique contemporary campaigns, while Eusebius cast his downfall as preordained within the divine plan of Christian history.

Constantine drew on Valerian’s example to proclaim God’s sovereignty, punishing wicked emperors and humbling Persians who had once gloried in capturing a Roman ruler. Later, Orosius extended Valerian’s punishment to the empire as a whole, arguing that the disasters of the third century flowed from its collective crimes against Christians.

In the sixth century, Peter the Patrician and Agathias examined the catastrophe for lessons about bureaucratic loyalty and Persian cruelty, while the Persian Khvadhaynamagh—preserved by al-Tabari—looked back to glorify Shapur, portraying Valerian as a captive builder and symbol of the king’s greatness.

Far from being forgotten, Valerian became a figure reshaped across centuries.

Ruins of the Palace of Roman Emperor Valerian in Bishapur city (Capital of Sasanian Empire) in Kazerun county, Iran. Public domain

Modern historians have sometimes downplayed his importance, but the disaster served as a formative defeat that inspired new narratives in diverse contexts. Central to its adaptability was the unfinished quality of the story: with his ultimate fate and burial unknown, Valerian could be recast as a trophy, a villainous persecutor, or a symbol of Roman resilience.

Unlike Nero, he did not become Antichrist or folk hero, nor did impostors arise in his name, yet both emperors shared the trait of an ambiguous end that invited speculation. Some accounts even left open the possibility of his eventual release, once rendered powerless by Shapur.

Unlike territorial losses that could be reversed or legionary standards that could be recovered, an emperor enslaved was beyond restoration. If Valerian overlooked the precedent of Crassus’ capture nearby in 53 BCE, later authors did not. By adapting his misfortune to their own needs, they ensured that Valerian would be remembered as Rome’s unforgettable imperial prisoner of war. (The Roman Emperor as Persian Prisoner of War: Remembering Shapur’s Capture of Valerian, by Craig H. Caldwell III in Brill’s Companions in Classical Studies. Warfare in the Ancient Mediterranean World)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: