The Antonine Plague: A Devastation that Reshaped the Roman Empire

The Antonine Plague was a turning point in the empire’s downfall—an often-overlooked epidemic that raged from 165 to 180 CE during the final years of the Antonine Dynasty.

It began with a whisper—a fevered breath carried on the winds of war. At first, it was nothing more than a distant murmur, a shadow lurking at the edges of the empire’s vast frontiers. Soldiers returned from distant campaigns, their victories overshadowed by an unseen specter.

The streets of once-thriving cities grew quieter, temples filled with desperate prayers, and physicians, powerless in their craft, looked on in horror. Rome had faced countless enemies before, but this one did not come with swords or siege engines. It crept through the veins of the empire itself, silent, insatiable, and utterly indifferent to the might of men.

A Silent Catalyst of Rome’s Decline

Many historians attribute the fall of the Roman Empire to internal instability, economic downturns, and weakened military defenses after the golden age of Pax Romana. However, there is no singular event that clearly marks the decline of Roman imperial dominance. The Antonine Plague was a turning point in the empire’s downfall—an often-overlooked epidemic that raged from 165 to 180 CE during the final years of the Antonine Dynasty.

As the first recorded epidemic in history, it resulted in the loss of 10% of the empire’s population, amounting to approximately five to ten million deaths, and significantly undermined the prestige of Roman power. The Roman world, once characterized by the phrase “Dominus Et Deus” (Lord and God), was now subject to the dominance of a force beyond human control—one that dictated the health, stability, and imperial future of Rome.

The Antonine Plague, also known as the Plague of Galen, is named after the Greek physician Claudius Galenus, who documented its effects in Methodus Medendi.

A painting dubbed Medicine in the Middle Ages by Veloso Salgado, Galen is in the middle. Public domain

The disease, which afflicted victims for nearly two weeks with a 25% mortality rate, is even attributed to have claimed the life of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Galen described its symptoms and healing process:

“On the ninth day a certain young man was covered over his whole body by an exanthem, as was the case with nearly all who survived.

Drying drugs were applied to his body. On the twelfth day he was able to get out of bed.”

"Of some of these which had become ulcerated, that part of the surface called the scab fell away and then the remaining part nearby was healthy and after one or two days became scarred over.

In those places where it was not ulcerated, the exanthem was rough and scabby and fell away like some husk and hence all became healthy."

Due to the lack of inscriptions dated between 167 and 180 CE, historians estimate a severe population decline—ranging from five to ten million deaths to a highly debated 33% mortality rate among the empire’s 75 million inhabitants. The disease likely originated in the Far East, brought back by Roman soldiers returning victorious from the Parthian Wars.

Many scholars believe it was a form of smallpox or typhus. The epidemic significantly reduced life expectancy, with Italy suffering the greatest impact, as it coincided with malaria and other seasonal diseases. The plague rapidly spread across the empire’s vast transit network, affecting Asia Minor, Egypt, Greece, and Italy.

At its peak, the plague claimed 2,000 lives per day in Rome. Despite its catastrophic consequences, it is often overshadowed by other major outbreaks, such as the Plague of Athens under Pericles and the Justinian Plague centuries later.

The Economic Devastation of the Antonine Plague

The Antonine Plague dealt a severe blow to Rome’s economy, causing widespread stagnation. Trade slowed, economic activity declined, and the value of goods depreciated. Records from Roman Egypt suggest that wages remained stable, but broader economic trends indicate serious disruptions across the empire.

Archaeological evidence, such as reduced air pollution and a decline in Iberian mining activities, points to a major decrease in industrial output. As the population declined, the land-to-labor ratio increased, leading to lower incomes and cheaper land values.

Between 158 and 219 CE, agricultural output suffered, with transaction records showing a sharp drop in wheat production and a rise in the consumption of luxury goods like wine. As demand shifted, the economy favored smaller, high-profit ventures over large-scale agriculture, setting the stage for future shortages. Over time, this shift contributed to a dramatic rise in commodity prices due to population recovery outpacing production.

Though some argue that food prices rose more quickly between 165 and 180 CE than during the Crisis of the Third Century, this comparison does not fully account for coinage policies and later Diocletian reforms. Nonetheless, declining wheat rents provide a clear indicator of economic distress.

Before the plague, land rents for major wheat-producing regions—Arsinoite, Oxyrhynchite, and Hermopolite—were stable at 7.5 to 8 artabas per aroura. By the late second century CE, these values had dropped to 5.5, 6, and 3.6 artabas, respectively, reflecting a sharp decline in agricultural profitability.

The depopulation crisis forced landlords to lower rent prices to encourage cultivation, but this strategy proved ineffective. By 180 CE, the empire harvested only 27.5% of the expected wheat yield, leading to widespread starvation. This prolonged agricultural failure hindered population and economic recovery.

The economic decline further deactivated industries, particularly factories and mines, exacerbating the downward spiral.

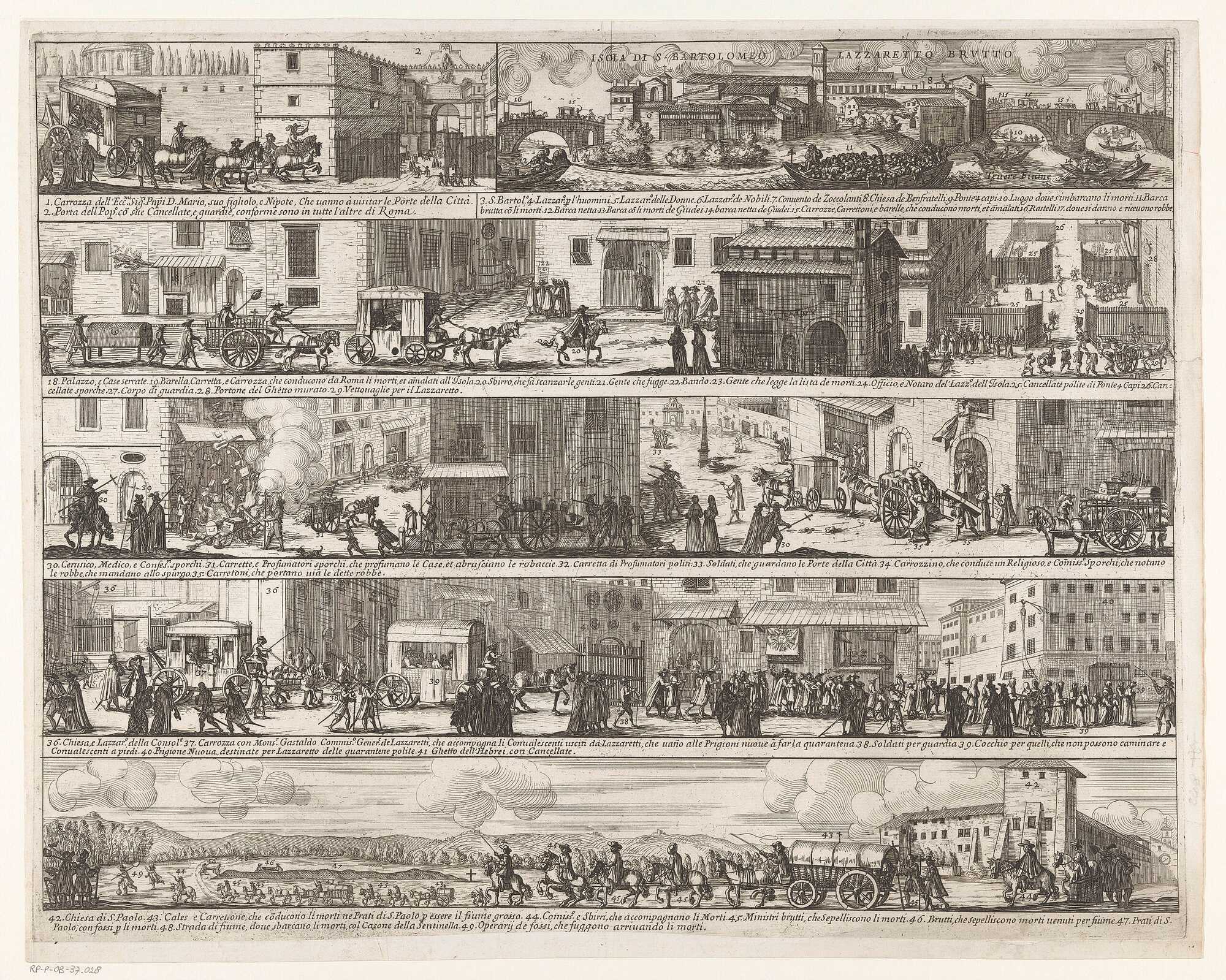

A painting from Michiel Sweerts and Workshop, dubbed Plague in an Ancient City (possibly Athens). Public domain

Even after the plague subsided, its economic aftershocks persisted. Wages in wheat units rose by 20%, while the nominal price of essential goods like wine and oil increased by nearly 50%. The situation was especially dire in Egypt, a region heavily reliant on grain exports.

As foreign demand surged, price levels spiked, worsening economic conditions long after the plague had ended. The inability of Roman citizens to afford basic necessities made economic survival increasingly difficult.

Faith in Crisis: The Shift from Paganism to Christianity

During the Antonine Plague, traditional Roman Pagan religious institutions experienced a decline in influence, while monotheistic faiths, particularly Christianity, gained followers across the empire. Throughout history, people of faith have turned to religion for comfort during crises—from the Pilgrims of the New World praying for their survival in the 17th century to the Jewish defenders at Masada choosing death over surrender.

In Rome, such spiritual reliance typically centered around the Greco-Roman god of healing, Asclepius, whose worship was introduced from Greece in 293 BCE. However, during the Antonine Plague, there is no clear evidence that Roman citizens overwhelmingly sought divine protection from Asclepius.

Modern quantitative research analyzing Latin inscriptions and epigraphic evidence suggests that Asclepius did not gain popularity during the epidemic. The number of inscriptions, monuments, and textual references dedicated to him remained stagnant.

This decline in faith during a medical crisis is a key indication of the weakening of traditional Roman religious practices and the growing appeal of monotheism, particularly Christianity.

A painting from Michiel Sweerts and Workshop, dubbed Plague in an Ancient City (possibly Athens). Credits: Wellcome Images, CC BY 4.0

Before the plague, Christians were a small and persecuted minority, estimated at 40,000 adherents—only 0.07% of the empire’s population. Despite being marginalized, many Christians, as recorded in biblical and Christian sources, provided care for the sick and extended aid even to non-believers.

In contrast, Emperor Marcus Aurelius responded to the crisis by restoring Pagan temples and monuments while continuing the persecution of Christians who refused to worship the Greco-Roman gods. Once again, Christians were blamed for the empire’s misfortunes.

However, their humanitarian response set them apart. Unlike the state-sponsored religious cults that focused on ritual and worship, Christians gained greater popularity because they offered direct help to those in need. This compassionate response contributed to a surge in conversions.

While the exact numbers remain unknown, by 180 CE, the Christian population had grown to 100,000 followers, reflecting a 150% increase. This rise in Christianity paralleled the decentralization of Pagan religious dominance and a growing acceptance of monotheistic faiths.

The influence of Christianity continued to shape imperial policies. Under Emperor Gallienus, the empire officially ended the persecution of Christians. Another epidemic, the Cyprian Plague, further contributed to the faith’s expansion. Named after Cyprian, the Christian Bishop of Carthage, the plague became a defining moment for Christian martyrdom.

Cyprian refused to renounce his faith and, like many early Christian figures, was executed for his beliefs. His death cemented his status as a Christian saint and reinforced Christianity’s growing reputation for resilience. (Antonine Plague: The Overlooked Turning Point in Roman Empire’s History, by Harrison H. Tang)

Rome’s Deadly Encounter with an Unseen Enemy

The Roman world frequently faced deadly epidemics, with historical records suggesting that major outbreaks occurred approximately every 10 to 20 years. However, the Antonine Plague stood out due to its unprecedented severity and rapid spread.

It became one of the defining events of Marcus Aurelius’ reign. When the plague first emerged, Galen—the only available medical observer—quickly abandoned Rome, where the disease had claimed nearly all his slaves. He later witnessed its return in 168 CE, which forced both emperors to leave Aquileia, with:

“one of them dying suspiciously soon on the journey home.”

The historian Dio recorded a later outbreak in 189 CE, stating that it "killed 2,000 people per day." Even two centuries later, Ammianus Marcellinus described the Antonine Plague as an event that:

“after generating the virulence of incurable disease (under Marcus and Verus), polluted everything with contagion and death, from the frontiers of Persia all the way to the Rhine and to Gaul.”

Cold winters and low rainfall were especially conducive to smallpox transmission, as evidenced by a detailed study of London deaths from 1659 to 1835. The outbreak in Aquileia in 168/9 was particularly severe in winter, with Galen recalling that:

“most of us died, not merely from the plague, but because the epidemic was happening in the depths of winter.”

Similarly, January and February 179 CE saw a significant rise in fatalities at Soknopaiou Nesos in Egypt. The timeline of epidemic outbreaks in China closely aligns with that of the Antonine Plague, suggesting a shared origin. China also experienced seasonal concentrations of deaths, with notable spikes in February 173, March 182, and the spring of 179.

The Vulnerability of Rome’s Slaves

Epidemics, including the Antonine Plague, disproportionately affected enslaved populations, whose harsh living conditions made them particularly susceptible. Slaves often endured cramped, communal sleeping arrangements and inadequate nutrition, factors that likely contributed to their high mortality rates.

As aforementioned, Galen recounts that the plague claimed nearly all of his slaves in Rome.

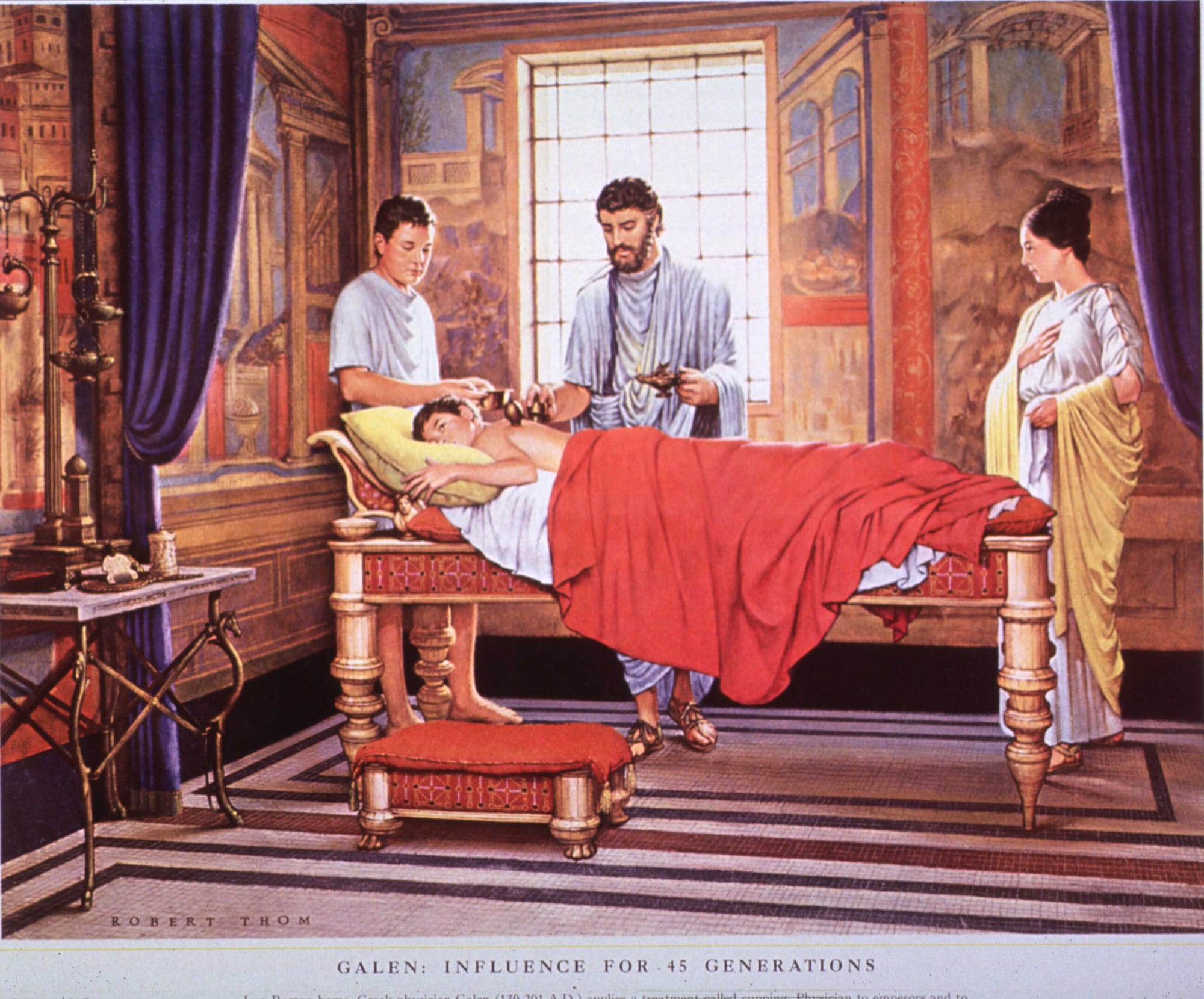

An illustration from the History of medicine in pictures, Galen cupping a patient. Credits: Rawpixel, CC0 1.0

Similarly, Aelius Aristides describes how an outbreak in Smyrna during the summer infected nearly everyone around him. At first, only a few of his servants fell ill, but soon the sickness spread, affecting both the young and the old. Aristides himself was the last to succumb, noting the horrifying speed of the disease:

“And if anyone tried to move, he immediately lay dead before the front door.”

Historical parallels reinforce the devastating impact of disease on enslaved and impoverished communities. Dionysius and Livy record that a plague in Rome in 451 BCE wiped out all the slaves and half the citizen population. Another outbreak in 428 BCE began as cattle disease before spreading to rural communities and slaves, eventually reaching the city.

A similar event in 174 BCE devastated livestock before affecting slaves so severely that their unburied bodies lined the roads. These patterns persisted into later periods—in 1419, over half of the plague victims in Cairo were slaves, and in 1815, bubonic plague in Noja, Apulia, initially struck only the poor.

While enslaved people are often underrepresented in ancient historical narratives, sources like Galen and Aristides highlight their extreme vulnerability during pandemics. The Roman annalists also acknowledge their plight, suggesting that severe outbreaks could cripple or decimate the labor force. Aelius Aristides, left with no one to care for him as his own slaves perished, was ultimately tended to by the slaves of the doctors who had come to treat him.

The Roman Army and the Deadly Spread of Plague

The risks posed by a large standing army in spreading disease under pre-modern conditions were immense. Frequent military mobilizations, unit transfers, and the furlough of soldiers created ideal circumstances for the rapid transmission of epidemics. Historical sources emphasize the devastating toll of the Antonine Plague on the Roman army.

Jerome asserts that by 172 CE, the army was nearly wiped out. Eutropius describes entire armies perishing, with nearly all the armed forces succumbing to disease, alongside massive losses in Rome, Italy, and the provinces. Orosius notes that the plague struck winter-quartered legions so severely that a three-year conscription drive at Carnuntum was necessary for the Marcomannic Wars.

The Historia Augusta records that many thousands of soldiers died, forcing Marcus Aurelius to replenish the legions by recruiting slaves, gladiators, bandits, and Germanic mercenaries. Further evidence from military inscriptions suggests dramatic upheaval.

A list of discharged legionaries from VII Claudia in Lower Moesia (195 CE) implies an unusually large intake in 169 CE, with 270 survivors—double the expected number after accounting for deaths in service. Another legionary inscription from Alexandria (168 CE) shows a shift toward recruiting men born in military camps, rather than from traditional recruitment cities, pointing to severe manpower shortages.

Additional army records reflect the plague’s impact in striking ways. Military discharge certificates (diplomata), which were regularly issued before the mid-160s, abruptly ceased after 167 CE and did not resume until a single instance in 177 CE.

Before the outbreak, numbers were stable, with 22 certificates in 160 CE and 12 in 164 CE, but the sudden halt suggests a collapse in army administration during the plague years. This disruption may have been further worsened by metal shortages caused by mining issues. (The Antonine Plague revisited, by R. P. Duncan-Jones)

Galen and the Antonine Plague: Identifying the Disease

The Antonine Plague holds a significant place in medical history primarily due to its association with Galen, the renowned Greek physician. As we mentioned, Galen had firsthand experience with the epidemic, witnessing its devastation in Rome in 166 AD and again during an outbreak among troops stationed in Aquileia in 168/9 AD.

While he meticulously recorded many medical conditions, his references to the plague remain scattered and incomplete. Unlike Thucydides, who documented the Athenian plague with future recognition in mind, Galen focused primarily on symptoms and treatment rather than providing a comprehensive account for later generations.

Due to the scarcity of details in Galen’s writings, historians have debated the exact nature of the Antonine Plague. The prevailing theory identifies it as smallpox, particularly in its hemorrhagic form, though other possibilities such as exanthematous typhus or bubonic plague have been considered.

However, the symptoms Galen described, particularly the exanthem (skin rash), strongly align with smallpox. He emphasized that the rash covered the entire body, turned black in many cases due to blood putrefaction, and often ulcerated—features consistent with hemorrhagic smallpox.

“In those who were going to survive who had diarrhea, a black exanthem appeared over the whole body.

It (the exanthem) was ulcerated in most cases and dry (no liquid oozing out) in all. The blackness was due to a remnant of blood which had putrified in the fever blisters, like some ash which nature had deposited on the skin.

Of some of these which had become ulcerated, that part of the surface called the scab fell away and then the remaining part nearby was healthy and after one or two days became scarred over.

In those places where it was not ulcerated, the exanthem was rough and scabby and fell away like some husk and hence all became healthy."

Galen also noted gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly severe diarrhea and black stools, which are frequently observed in hemorrhagic smallpox due to intestinal bleeding. He observed that patients who did not exhibit black stools often developed the characteristic black rash instead, aligning with modern medical understanding of the disease's progression.

While Galen’s incomplete description leaves some room for debate, the detailed account of the rash, fever, ulcerations, and internal bleeding provides strong evidence that the Antonine Plague was indeed smallpox. The virulent nature of the outbreak, its high mortality rate, and the widespread devastation it caused suggest a particularly severe strain of the disease, with hemorrhagic smallpox being the most likely culprit.

“Those afflicted with plague appear neither warm, nor burning to those who touch them, although they are raging with fever inside, just as Thucydides describes (in the Athenian plague).”

Comment. 1 in Hippocratis Libr. 6 Epidemiorum

“In many who survived, black stools appeared, mostly on the ninth day or even the seventh or eleventh day.

Many differences occurred.

Some had stools that were nearly black; some had neither pains in their excretions, nor were their excretions foul smelling.

Very many stood in the middle. If the stool was not black, the exanthem always appeared.

All those who excreted very black stools died.

De Atra Bile (V 104–148 K), On Black Bile

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: