Quintilian: A Theory of Education that Left its Mark from Antiquity Onwards

From Spain’s quiet frontier to Domitian’s court, Quintilian shaped Rome’s moral voice. His Institutio Oratoria united eloquence and virtue, teaching that only the good man can truly speak well.

In an age when power was measured by words as much as by swords, Quintilian shaped Rome’s voice. Born in Hispania and educated in the capital, he rose to become the Empire’s foremost teacher of rhetoric — a man who believed eloquence was not merely technique but virtue in speech.

His Institutio Oratoria, the most comprehensive treatise on education and oratory ever produced in antiquity, guided students from cradle to courtroom, blending moral discipline with intellectual rigor. To Quintilian, the perfect orator was not simply persuasive; he was good, for only a good man could truly speak well.

Quintilian: From the Provinces to the Heart of Rome

Born in Calagurris (modern Calahorra) on the river Ebro around 35 CE, Quintilian rose from Spain’s quiet hinterland to become the Roman Empire’s greatest teacher of rhetoric. His province, Hispania Citerior, was known, as Pliny wrote, for its iudicium et gravitas — its “good judgment and seriousness.”

These were the very qualities that defined Quintilian himself. Although later generations recorded his Spanish origin, his own writings reveal little trace of it. Long residence in Rome made him, in spirit, a citizen of the capital — yet one whose provincial roots gave him sobriety, discipline, and moral steadiness.

He came from a family of rhetoricians. His father taught the art of speech, and an older Quintilian mentioned by Seneca may have been his grandfather — suggesting that eloquence was the family’s inheritance. Whether raised first in Spain or brought early to Rome, the young Quintilian received the best Greco-Roman education. He was likely bilingual from infancy, hearing Greek nurses at home and learning both languages in parallel.

“It is the nurse,”

he wrote,

“whom the child first hears and imitates.”

From these beginnings he would build his lifelong conviction that moral character must shape speech as much as grammar or logic.

At twelve he entered the grammar schools, Greek and Latin alike, where he was trained in:

“the art of correct speaking and the explanation of the poets.”

His teachers still wrote seruom for servum and banned hybrid words like piratica or fabrica, reminders of a Latin still in motion. Alongside grammar came mathematics and music —

“for,”

he noted,

“no discipline stands alone.”

The final step was the rhetorical school, where ambition burned fiercely: pupils declaimed in ranked order, striving each month to remain at the head of the class. Quintilian recalled with wry humor one popular exercise:

“Why is Venus armed at Sparta?”

or

“Why is Cupid believed to be a boy with wings and arrows?”

myth turned into training for logic and persuasion.

He advanced rapidly. Rejecting teachers who detained pupils:

“to prolong their wretched fees,”

he left the school early and began his career at the bar, much as Pliny did in youth. By his own counsel,

“the student, having gained some mastery of invention and style, should choose an orator to follow and imitate.”

For Quintilian, that model was Domitius Afer, the brilliant but morally ambiguous advocate of Gaul. Tacitus condemned Afer for greed and cruelty; Quintilian, however, revered his professional mastery, recalling how the old man taught him to question witnesses and how Afer would sigh,

“It is all over with our profession.”

Their exchanges ranged beyond the courtroom — when asked who came nearest to Homer, Afer answered,

“Virgil — nearer to first than to third.”

By the 60s CE, Quintilian had made his name as an advocate and soon returned to Spain, where he practiced law and met Galba, then governor of Tarraconensis. When Galba became emperor in 68, he summoned Quintilian to Rome — a call that changed his life. Quintilian was the first to hold a publicly funded chair of rhetoric, his salary set at 100,000 sesterces, an honor later poets would recall with awe. Juvenal quipped about wealthy parents begrudging Quintilian his two thousand sesterces, proof of his eminence and prosperity.

He taught for twenty years, guiding pupils who would later fill Rome’s courts and Senate. His teaching blended rigor with conscience: rhetoric, he held, must serve justice, not vanity. He continued to plead cases, among them the defense of Berenice, mistress of Emperor Titus, and earned Martial’s tribute as “the glory of the Roman bar.” His success, he admitted, came not from dazzling wit but from diligence —

“to know every document, to question every witness, and to consider the cause from both sides.”

Retiring in his later years, he dedicated himself to writing. His Institutio Oratoria distilled a lifetime’s learning — a complete education of the orator from cradle to perfection. Domitian honored him with consular insignia and entrusted him with the emperor’s great-nephews, the young heirs of the Flavian house.

“How could I spare any pains,”

Quintilian wrote,

“in shaping their character, that they might deserve the praise of so chaste a guardian of morals?”

Such loyalty, however, placed him in a perilous proximity to power. When Flavius Clemens and Domitilla, the boys’ parents, fell under charges of “atheism” — likely Christianity — Quintilian remained silent. Perhaps, as he wrote bitterly elsewhere,

“one cannot be too careful under a despotism.”

He endured personal tragedy: his wife died young, and both sons followed her. The Institutio closes with the voice of a man who has lost much yet remains steadfast:

“I have long retired; death may overtake me before my work is done.”

He probably did not live beyond the first years of Nerva’s reign.

Quintilian’s name stands for the union of eloquence and ethics. His Rome was not that of conquest but of conscience — a Rome where the orator’s highest duty was to truth, and where, in his own words,

“the good man who speaks well” (vir bonus dicendi peritus)

was the true measure of civilization. (Quintilian: A Biographical Sketch, by M. L. Clarke)

The Measure of Quintilian: Virtue, Eloquence, and the Roman Ideal

Quintilian’s reputation rests not only on his mastery of rhetoric but on the moral vision that shaped his teaching. In an age when eloquence was too often divorced from virtue, he restored their unity, arguing that:

“the good man, skilled in speaking” (vir bonus dicendi peritus)

was the only true orator. The formula, deceptively simple, defined an entire philosophy of education — one where character was the foundation of art.

He lived at a moment when the old Republic’s civic eloquence had waned, and rhetoric risked becoming an ornament of tyranny. Yet Quintilian stood apart. He refused to sever speech from ethics, insisting that the orator must not merely persuade but deserve to persuade. In his view, no amount of technical skill could redeem corruption of soul.

“It is not enough,”

he warned,

“to know what should be said — one must also be worthy to say it.”

Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria was the summation of this creed — a vast architecture of moral and intellectual formation. It led the student from infancy to maturity, shaping not only the voice but the conscience. He envisioned education as the slow, deliberate growth of judgment (iudicium), nurtured by memory, imitation, and virtue.

The process began at home, with the choice of a nurse of pure speech and morals. From there, the young mind advanced through grammar, literature, and philosophy, each stage meant to refine both intellect and character.

For Quintilian, knowledge was inseparable from moral purpose. He admired the great stylists of the past — Cicero above all — yet he measured them by ethical gravity, not verbal brilliance. The orator’s task was to defend truth, not to dazzle with artifice.

“Art is perfected by nature, and nature by art,”

he wrote, blending Stoic integrity with Roman practicality. His method united the moral discipline of the philosopher with the precision of the rhetor.

Quintilian’s influence lay in his moderation. He rejected both the austerity of pedants and the excess of declaimers. The true orator, he taught, must combine wisdom with emotional power — a harmony of reason and feeling that mirrored the balance of the well-governed state. He cautioned against false passion:

“Let the heart feel what the lips utter.”

Such restraint, rare in his age, gave his teaching its lasting dignity.

His work was both technical and ethical, offering Rome an ideal of eloquence as moral service. To speak justly was, for him, to act justly. He turned rhetoric from a weapon of ambition into an instrument of conscience. The Institutio thus became not merely a manual but a vision of civic virtue preserved through education. In its pages, speech was the breath of duty — a means by which empire itself might recall its better self.

Quintilian’s legacy endured because it reconciled two traditions: the Roman sense of law and order with the Greek pursuit of moral beauty. He gave form to a principle as old as the Republic and as enduring as the Empire — that words, when rightly used, are the guardians of the soul. (An Estimate of Quintilian, by George Kennedy)

The Architecture of Eloquence: Inside Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria

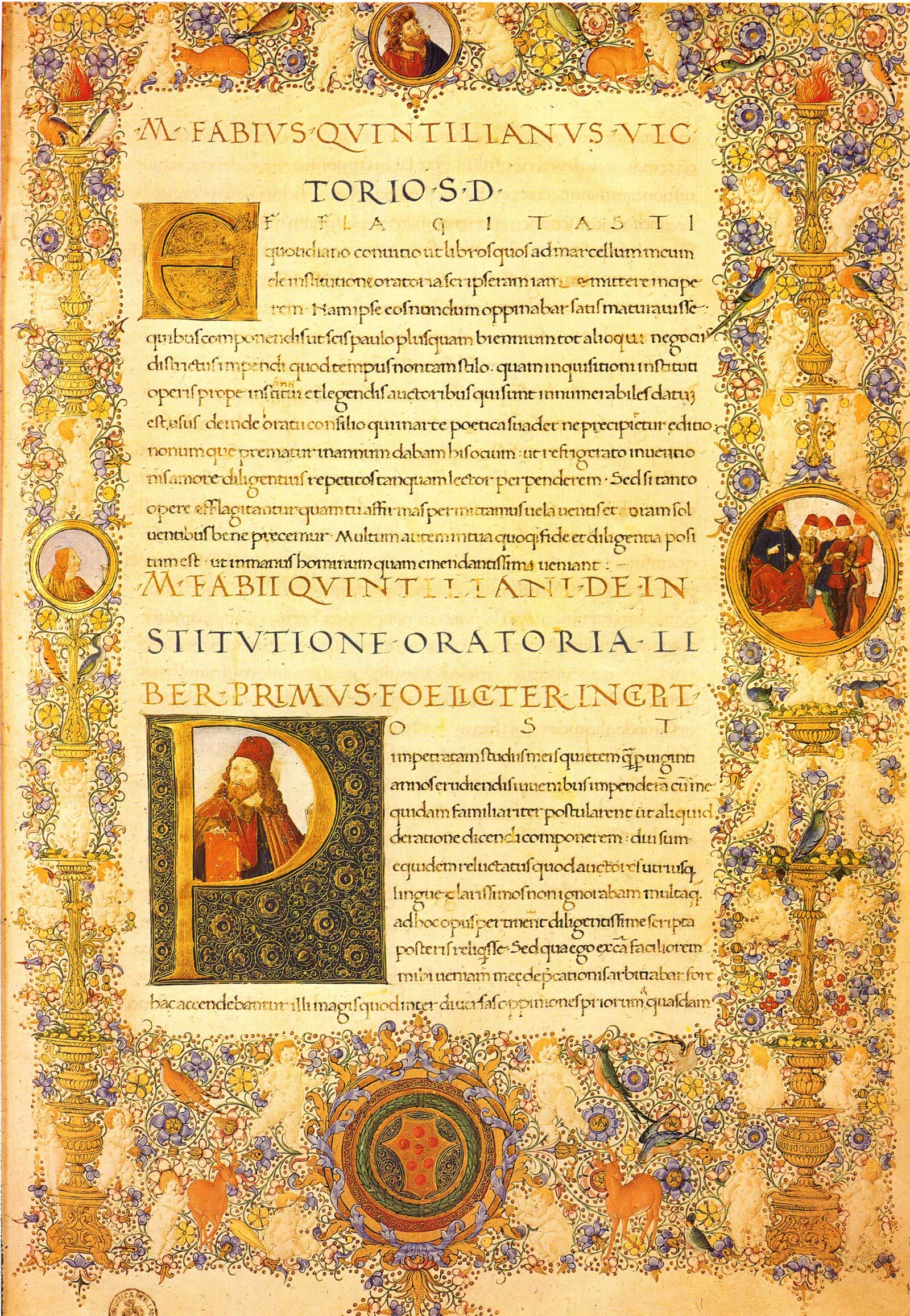

Around 95 CE, a retired teacher Marcus Fabius Quintilianus entrusted to his friend, the bookseller Trypho, one of the most ambitious intellectual works of antiquity — the Institutio Oratoria, or The Orator’s Education.

Across twelve lengthy rolls of papyrus, nearly 700,000 words in total, Quintilian undertook what he called an audacious aim:

“I am proposing to educate the perfect orator.”

For two years, he devoted his life to this project, consulting countless sources and shaping his long experience into a single system of moral and rhetorical training. His letter to Trypho — something like a modern preface — reveals a mix of persuasion and fatigue. Trypho, sensing a best-seller, urged him to publish, while Quintilian, already honored and wealthy, had little to gain but posterity.

Writing for profit was unthinkable for a man of his rank; only the bookseller’s staff of scribes would benefit commercially. His motive was different: the preservation of Roman eloquence through the education of conscience.

In his General Preface, Quintilian explains why he wrote. After two decades of teaching, he wished to reconcile conflicting theories of rhetoric and to provide a complete guide for his friend Marcus Vitorius Marcellus and the boy Geta, to whom the work is dedicated.

Unauthorized notes from his lectures were already circulating, and he feared that partial versions might distort his principles. His solution was to produce the definitive map of an orator’s life — from cradle to old age — an encyclopaedia of virtue and voice.

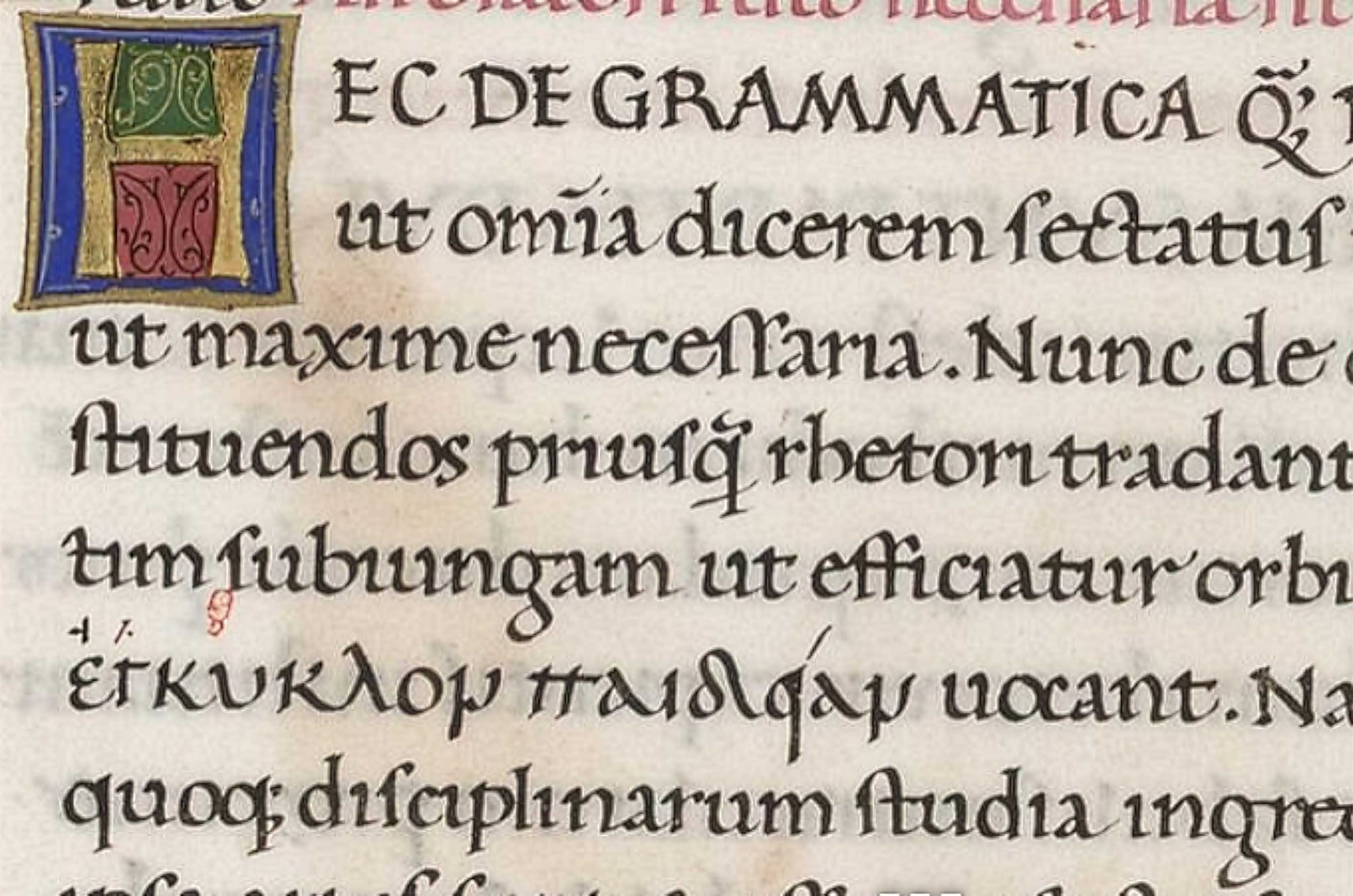

The Twelve Books of Formation

Quintilian carefully outlines the design of his monument to education.

- Book I begins before the rhetor’s art, teaching the earliest formation of speech, moral discipline, and home education.

- Book II turns to the foundations of rhetoric itself, defining its nature and aims.

- Books III to VII explore invention and disposition — the finding and ordering of arguments — what he calls “the sinews of speech.”

- Books VIII to XI cover style, memory, and delivery, the outward grace that animates thought.

- Book XII stands apart, portraying the finished orator: his character, his conduct in court, his retirement, and his intellectual afterlife.

The sequence moves from infancy to maturity, from theory to practice, and finally to the moral philosophy that must crown eloquence.

“I shall there discuss,”

he writes,

“his character, the principles of undertaking, preparing, and pleading cases, his style, the end of his active career, and the studies he may undertake thereafter.”

A Method for the Whole Man

Quintilian defends the scale of his work with clarity and irony.

He refuses to write another:

“dry textbook,” (nudae artes)

that

“drains off all the juice of the mind and exposes the bones.”

His goal was not to produce a skeleton of rhetoric but a living body — sinew, flesh, and spirit united. To teach eloquence, he insists, one must nourish the student’s powers of judgment and moral sense, not merely the tongue.

In this vision, rhetoric is inseparable from ethics. The orator, trained from childhood in purity of speech and thought, matures through grammar, literature, and philosophy into a figure capable of uniting wisdom with persuasion. The teacher’s task is to cultivate both the intellect and the heart, guiding a youth whose earliest words —

“for the words first heard cling longest”

will shape the citizen he becomes.

The Institutio Oratoria thus unfolds as four intertwined works: a treatise on education, a manual of rhetoric, a reading guide to the finest authors, and a moral handbook for the vir bonus dicendi peritus — “the good man skilled in speaking.” The rhetorical books themselves, nine in number, are only instruments; the true design lies in the ethical structure built around them. Eloquence is not an end but a form of virtue expressed in words.

Reading the Monument

For ancient readers, such a monumental text demanded patience. Divided into twelve scrolls without modern aids, it could only be navigated through Quintilian’s own plan. Later copyists added divisions, headings, and chapters; Renaissance printers supplied numbered sections; modern translators, like Donald A. Russell, imposed fresh order upon its labyrinth. Yet no amount of segmentation can diminish its unity of purpose.

Quintilian wrote as a craftsman of civilization. Each page mirrors the balance he preached: discipline tempered by humanity, method softened by moral vision. He often interrupts his argument to consider opposing views, to offer personal advice from the courtroom, or to apologize for excessive detail —

“I may seem to dwell too long,”

he admits,

“but nothing is unnecessary in forming the perfect orator.”

This generosity of thought is what makes the Institutio timeless. It is less a system than a life unfolded in twelve acts — a journey from the first word of a child to the last counsel of an old teacher who believed that eloquence, rightly taught, could refine the world.

The Making of a Monument: How Quintilian Wrote the Institutio Oratoria

Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria, appears to have been written in the very sequence we read today. Only its short preface, the letter to his bookseller Trypho, came last. Some modern editors think the General Preface was also a late addition, but its forward-looking tone and future-tense verbs show it was conceived as a prologue, not an afterthought.

That the letter to Trypho survived at all is remarkable. It was never meant as part of the book, merely a covering note for delivery. Perhaps Trypho preserved it as an advertisement for his distinguished author — a bit of literary marketing that scribes continued to copy over the centuries. Yet within it lie small but telling clues about how the Institutio was made.

Quintilian tells Trypho that he had already finished the work before the bookseller approached him. The treatise, he explains, was first written for his friend Marcus Vitorius Marcellus and his son Geta, not for the general public. He spent

“a little more than two years”

completing it, then, following Horace’s advice in the Ars Poetica,

“put it away, so as to go over it again with a reader’s eyes.”

The act of setting a finished work aside for revision was part of his method, as it was for any disciplined rhetor. In Book X, he urges his students to correct their written speeches before delivery, conceding that though orators may be pressed for time,

“the work must be returned to the file,”

since

“the same care that shapes the speech refines the speaker” .

Quintilian seems to have written the twelve books gradually, sending each new installment to Marcellus as it was completed. In the preface to Book IV he remarks that his appointment as tutor to the emperor’s grandnephews had

“changed the nature of our relationship”

a clear sign that the correspondence continued through composition. Later, in Book VI, he apologizes for delay:

“When grief subsides, I shall have some justification for asking pardon for my slowness, caused by the death of my son”.

These moments of personal voice — grief, fatigue, renewed resolve — mark the progress of a living work rather than a polished academic system. It ends as it began, in friendship:

“This, then, Marcus Vitorius,”

he writes in the closing line,

“is the best contribution I think I can personally make to the teaching of oratory”.

Writing for Posterity, Not Publication

Quintilian never meant to publish in the modern sense. “Publication” in ancient Rome had little to do with business. There were no copyright laws, no printing houses, and no royalties — anyone could copy a text and sell it.

Speeches were often taken down by shorthand writers and sold as scrolls; authors might read their work aloud to select audiences in a recitatio, or entrust copies to friends. Virgil had read passages of the Aeneid to Augustus himself.

Quintilian, comfortably wealthy from his career and imperial pension, would have regarded writing for profit as undignified. His motive was civic and moral: to set down a complete programme of education, a legacy for Rome. What seems to him a burden of two years’ labor appears to us astonishing speed — seven hundred thousand words composed, edited, and copied with only wax tablets, parchment, and the hands of slaves.

The Teacher at Work

It is easy to imagine Quintilian’s study: wax tablets stacked like pages of a private notebook, the stylus scratching into their smooth surface. He may have followed what we might call today a “storyboard” — a written plan or checklist of the twelve books to keep track of what had been completed. His adherence to his outline is clear: the work follows the order promised in the General Preface almost exactly, with only minor slips. At times, he loses his place —

“I might be thought by some to have left this out”,

he admits when repeating an earlier point on judgment; elsewhere, he says,

“I spoke (I think in Book Seven)...”.

Such self-corrections show that no later editor “cleaned” the manuscript; what we read today is the voice of a writer caught in motion, not after revision.

Scholars have called the Institutio, the most complete and detailed collection of the theories and techniques of communication in Greece and Rome up to the first century. Indeed, it feels encyclopedic — yet Quintilian himself remained humble about its limits. Discussing figures of speech, he concedes that more remain to be discovered. On the proofs of argument, he writes,

“I have not the confidence to assert that this is all there is; indeed I urge further research”.

Even where he sounds most certain, he reconsiders — on arguments and on the number of issues — treating study as a living art rather than a closed ledger.

The Tools of Composition

In Book X, Quintilian turns from philosophy to the physical act of writing. He distinguishes three methods: dictation, writing on parchment, and writing on wax tablets. Dictation,

“the luxury of the rich,”

he says,

“achieves neither the accuracy of writing nor the spontaneity of speaking”.

The scribe might be slow, or misunderstand, and:

“our chain of thought may be broken by delay or irritation.”

As for surfaces, his preference is clear:

“It is best to write on wax, where it is easiest to erase,”

unless poor eyesight demands parchment — though parchment:

“delays the hand and breaks off the flow of thought”.

Wax tablets were the working pages of Rome — small wooden boards covered in wax, joined by cords, and inscribed with a stylus whose blunt end smoothed away errors. They were portable, erasable, and ideal for teaching or composing drafts.

In Book I, Quintilian recommends them to beginners:

“Let the child write first on wax, so that mistakes may be corrected easily”.

Later, in Book XI, he describes orators preparing their speeches on such tablets before transferring them to more permanent rolls.

The Institutio must have followed that process. Each passage was probably drafted on wax, then copied onto papyrus by household scribes. Quintilian, like Cicero before him, almost certainly dictated the final version to a secretary once the structure was fixed.

Cicero’s scribe, Tiro, had invented shorthand to record such dictation; Quintilian may have had a similar servant, though he never names one. He seldom names anyone — not even his late wife or his two sons.

His library, meanwhile, must have been vast. He cites nearly eighty authors, from Plato to Seneca, quoting four major rhetorical treatises and most of Cicero’s speeches. In twenty years of teaching he had gathered a scholar’s treasury, likely by purchase or by private copying, for public libraries were rare. His mastery of sources gives the Institutio its depth: a lifetime’s reading distilled into one continuous work.

The making of the Institutio Oratoria was an act of endurance as much as intellect. Between teaching, loss, and imperial service, Quintilian sustained two years of unbroken writing — drafting, revising, dictating, and assembling the twelve rolls that would define rhetorical education for a millennium. His method combined rigor with humility, perfection with progress — the mark of a teacher who believed wisdom itself must remain a living art.

“Prolonged study would be waste of time,”

he confessed,

“if one were forbidden to improve on one’s past opinions.”

That single line captures the restless spirit of a teacher who believed that wisdom itself must remain a living art. (The Oxford Handbook of Quintilian, edited by Mark Van Der Poel with Michael Edwards and James J. Murphy)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: