Orosius: The Fall of Rome Through Christian Eyes

From Braga to Jerusalem, Orosius carried letters, relics, and arguments—but his legacy rests on the Historiae, a sweeping Christian vision of world history that shaped medieval thought.

When the Goths stormed Rome in 410 A.D., the shockwaves spread far beyond the crumbling walls. Pagan writers claimed the disaster proved Christianity had doomed the Eternal City, leaving it abandoned by its gods.

To answer them, Augustine began his City of God and turned to his disciple Orosius, urging him to write a sweeping history that would prove calamities had always haunted humanity, long before Christ. Rising to the task, Orosius crafted the most extensive surviving summary of Rome’s past, dating events from the city’s foundation in 751 B.C., weaving Roman and Greek history together, and reshaping the narrative of an empire through Christian eyes.

The Shape of a Christian Historian

Aulus Orosius was most likely born at Bracara, today’s Braga in Portugal, sometime between 380 and 390, though some traditions suggest Tarraco in Spain. Evidence, however, points more strongly to Bracara. Despite his prominence, few of his contemporaries wrote about him, and only a sketchy outline of his life can be reconstructed. His additional name, Paulus, was first recorded by Jordanes in the Getica of the mid-sixth century.

Nothing certain can be said about Orosius’ early years in Hispania, except that he became a presbyter and played a leading role in debates with the Priscillianists and Origenists. His writings show that he was well trained in both pagan and Christian culture. He was familiar with the major Roman authors, especially Vergil, Horace, and Cicero, and had studied in the rhetorical schools, while also being firmly grounded in Christian belief and recognized for his strong faith.

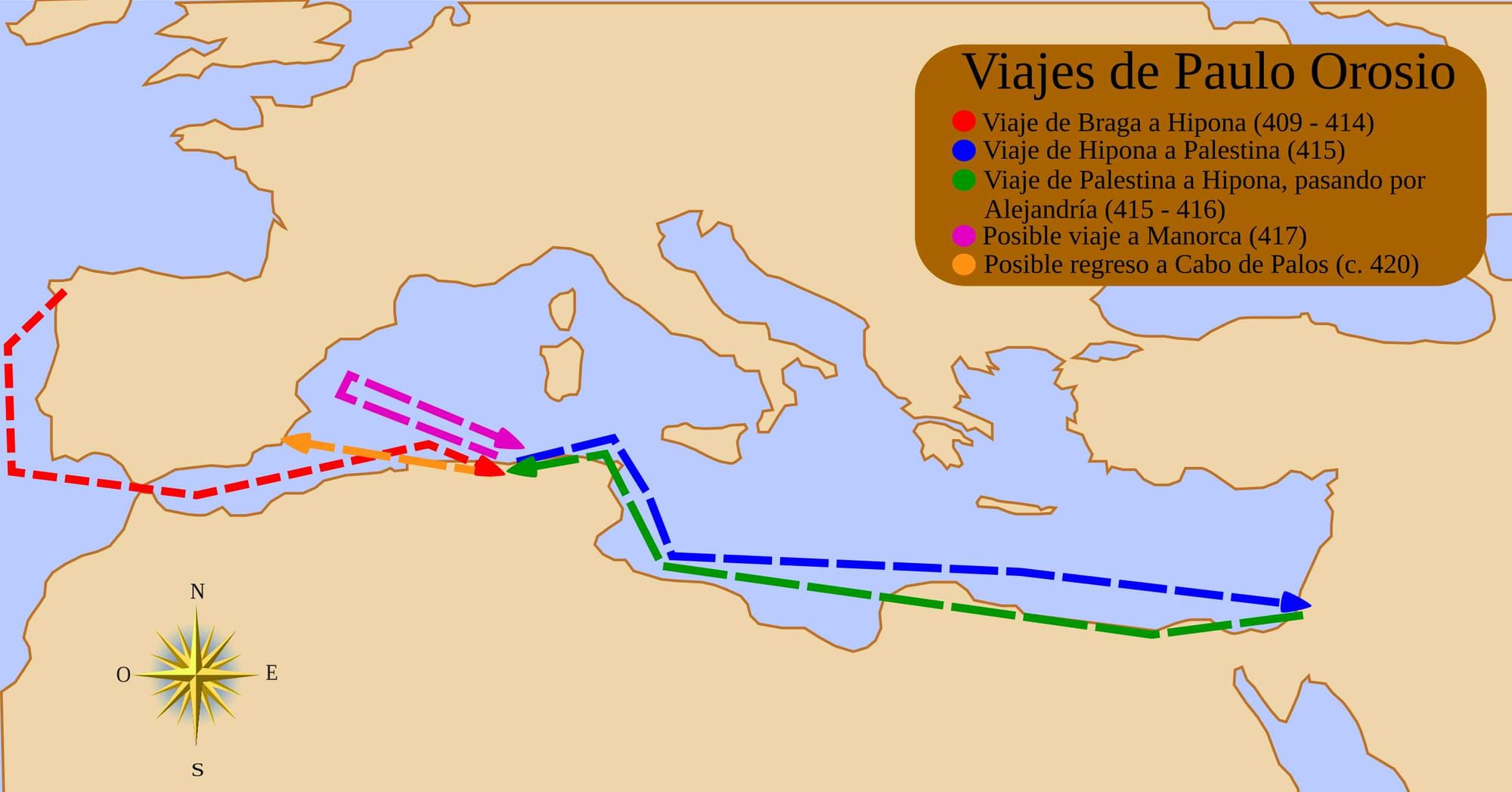

Around the age of thirty, in 413 or 414, Orosius left his homeland. He explains only that he departed sine voluntate, sine necessitate, sine consensu,(without will, without necessity, without consent) and that divine providence guided his ship during a storm to the African coast near Hippo, where Augustine was living. Some believe he fled because of the devastation of the Alans and Vandals in Hispania; others suggest he sought counsel against heresy.

In any case, he was warmly received by fellow Christians and soon went to Augustine to discuss doctrines of the soul, which were under attack by the Priscillianists and Origenists. To brief Augustine, he wrote the Commonitorium de errore Priscillianistarum et Origenistarum in 414, to which Augustine responded with Ad Orosium contra Priscillianistas et Origenistas.

Still unsatisfied, Orosius resolved to visit Jerome in Palestine. Augustine supported this plan and sent him with a long letter of introduction (Epistle 166). Augustine described Orosius as:

“a religious young man, a brother in the Catholic fold, in age a son, in dignity a fellow priest, alert of mind, ready of speech, burning with eagerness, longing to be a useful vessel in the house of the Lord…”

Orosius traveled to Palestine in 415, passing through Egypt and venerating Christian shrines along the way. There he joined Jerome and others in opposing Pelagius, who was then spreading his teachings.

The conflict reached a council in Jerusalem convened by Bishop John. Orosius defended Augustine and Jerome’s position, but his words were misinterpreted by an interpreter, and John accused him of blasphemy. Because Pelagius affirmed that man could not avoid sin without divine grace, he was not condemned, while Orosius was charged with maintaining that man could not avoid sin even with grace.

To answer these charges, Orosius composed the Liber apologeticus, which presented the Jerusalem council in detail and systematically explained Augustine and Jerome’s views on free will and Christian perfection. In 416, Orosius left Palestine, possibly via Minorca, but most likely sailed first to Africa, as Augustine had requested.

He carried a letter from Jerome and writings from the Gallic bishops Hero and Lazarus, who were engaged in the Pelagian struggle, as well as relics of St. Stephen with an explanatory letter by Lucian. On Minorca, he deposited the relics in a church where they soon became the focus of widespread devotion.

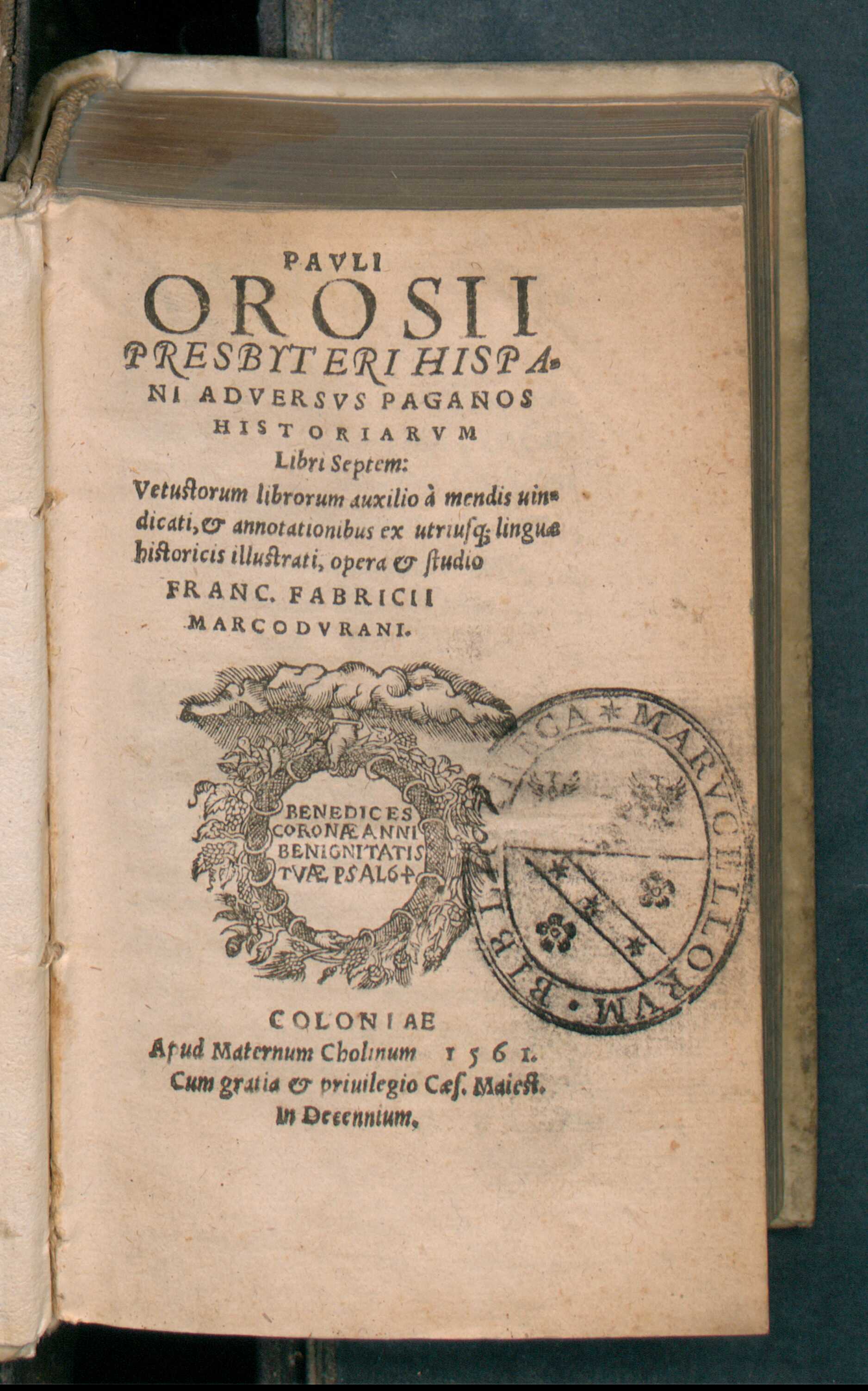

Unable to return to Hispania because of Vandal incursions, Orosius went back to Augustine in Africa. At Augustine’s request, he began the Historiae adversus paganos. This seven-book work, finished around 418, was meant to supplement Augustine’s City of God.

While Augustine had argued that calamities befell Rome both before and after Christianity, Orosius extended this proof across all of world history. He traced human affairs from the Flood to his own time, emphasizing that God determined the destiny of nations. Orosius identified four great empires in succession: Babylon, Macedon, Carthage, and Rome, a framework widely accepted in the Middle Ages.

The Historiae begins with a geographical overview and then proceeds: Book One, from the Flood to Rome’s founding; Book Two, Rome to the Gallic sack, Persia to Cyrus, Greece to Cunaxa; Book Three, Alexander and his successors alongside Roman history; Book Four, Rome to Carthage’s destruction; Books Five through Seven, Roman history down to Orosius’ own era.

Though hastily written and often borrowing heavily from sources such as Scripture, Jerome’s edition of Eusebius, Livy, Eutropius, Suetonius, Florus, and Justin, the Historiae adds details not preserved elsewhere, especially after 378 CE. His apologetic intent led him to highlight disasters and sometimes choose the more exaggerated version of an event to illustrate his point.

After completing this work, Orosius disappears from the record, and his fate remains unknown. His reputation endured, however, largely through his association with Augustine. In 494 Pope Gelasius praised the Historiae, securing its authority in the Church.

Nearly two hundred manuscripts survive, and while Augustine’s City of God eclipsed it in learned circles, Orosius’ work remained widely read. It influenced Isidore of Seville and Otto of Freising, and was even translated into Anglo-Saxon by Alfred the Great. (The fathers of the church – Paulus Orosius: The seven books of history against the pagans, translated by Roy J. Deferrari)

The Historiae: Universal History Through the Hand of Providence

The Historiae adversus paganos was not a new tale but an old one retold through providence. Orosius assumed the triumph of Christianity and set about proving that God’s presence had always guided human history.

He framed calamities of the pagan past as divine punishment for ignorance and showed that with Christ the world had entered an age of improvement. In doing so, he created the longest surviving universal history from antiquity, blending Roman chronology with Greek digressions, epitome with apologia, and theology with chronicle.

What makes the work exceptional is its afterlife. With over 275 manuscripts in circulation—an astonishing survival compared to Ammianus or Arnobius—Orosius’ Historiae became the medieval standard for understanding antiquity.

Pope Gelasius called it “indispensable,” Gennadius praised him as “most eloquent and learned,” and its echoes stretched from Jordanes and Isidore to Bede, Dante, and Petrarch. The opening world-survey circulated as an authoritative text on geography, while Orosius’ portrait of Alexander the Great helped shape the medieval Alexander Romance.

Though Renaissance humanists dismissed him as ignorant, and modern scholars long derided his “naïve providentialism,” more recent work has uncovered Orosius’ rhetorical skill and the originality of his vision. Rather than a poor imitation of Augustine, he emerges as an independent author who forged a providential framework for world history—one that would dominate European thought for centuries.

Between History, Breviarium, and Apologia

Orosius’s work, defies easy categorization. For over 1,600 years it has circulated widely, yet questions about its purpose, genre, and authorial intention remain unresolved. Scholars note that Orosius carefully avoided calling his work a “history” in the Prologue, where he refers to it instead as an opus, a volumen, or an opera. While he drew on “histories and annals” at Augustine’s request:

“You bade me, therefore, discover from all the available records of histories and annals whatever instances past ages have afforded of the burdens of war, the ravages of disease, the horrors of famine, of terrible earthquakes, extraordinary floods, dreadful eruptions of fire, thunderbolts and hailstorms, and also instances of the cruel miseries caused by parricides and disgusting crimes.

I was to set these forth systematically and briefly in the course of my book.”

Paulus Orosius, Histories against the Pagans

He positioned his project as fundamentally different from earlier pagan writers, who began with Ninus of Assyria. Orosius criticizes them for omitting “3,184 years” of human history and for wasting the subsequent “2,015 years” between Ninus and Christ:

“From Adam, the first man, to Ninus, whom they call "The Great" and in whose time Abraham was born, 3,184 years elapsed, a period that all historians have either disregarded or have not known.

But from Ninus, or from Abraham, to Caesar Augustus, that is, to the birth of Christ, which took place in the forty-second year of Caesar's rule, when, on the conclusion of peace with the Parthians, the gates of Janus were closed and wars ceased over all the world, there were 2,015 years.”

He insists instead on the authority of Scripture:

“My subject, therefore, requires a brief mention of at least a few facts from those books which, in their account of the origin of the world, have gained credence by the accuracy with which their prophecies were later fulfilled.

I used these books not because I purpose to press their authority upon anyone, but because it is worthwhile to repeat the common opinions that we ourselves all share.”

Brevity is a constant concern in the Historiae. Orosius repeatedly apologizes for omissions—“for the sake of brevity, I have passed over” —and admits to the “knotty problem” (sollicitudo nodosior) of reconciling universality with conciseness. He concludes that “brevity is always obscure” (obscura brevitas), but tries to strike a balance by presenting “the essence of things” while omitting detail.

This balancing act shapes the narrative voice. At times Orosius writes in the style of a neutral breviarium, offering facts in chronological order, often ab urbe condita (from the founding of the City i.e., Rome). Yet the narrative regularly shifts into emotional commentary. After describing Alexander’s conquests, he exclaims:

“O callous soul of man, and heart ever inhuman!

Did not my eyes fill with tears as I reviewed the past in order to prove that calamities have recurred in cycles throughout all ages; did I not weep as I spoke of evils so great that the entire world trembled from death itself or from fear of death?

Was not my heart torn with grief?

As I pondered over all this, did I not make the terrible experiences of my ancestors my own, seeing in them the common lot of man?”

Similar passages appear after the history of Athens and the First Punic War. These rhetorical intrusions direct the reader to view the past not as glorious but as tragic, reinforcing the apologetic aim.

Orosius also competes with his models. He borrows from Eutropius’s Breviarium, dating events ab urbe condita, but extends the system backwards to Creation and forwards to his own time. Where Eutropius gave 850 years from Rome’s founding to Nerva, Orosius corrects him:

“In the eight hundred and forty-sixth year of the City - although Eutropius { 8.1.1 } says that it was the eight hundred and fiftieth - Nerva was proclaimed emperor {96 A.D.}”

This reveals Orosius’ independence, his insistence on chronological precision, and his determination to align universal history with Rome as the chosen empire.

The question of audience remains contested. The narrator often addresses nonbelievers:

“These arguments, though advanced with great force and truth, do require, after all, a devout and willing listener.

My present audience, however, whether or not they may come to believe at some future time, are certainly unbelievers now.

Therefore I shall bring forward rather quickly arguments which, though my opponents may not approve, they certainly cannot disprove.

Now, within the limits of our human comprehension, we and our opponents both revere religion and acknowledge and worship a higher power.

The difference lies only in the nature of our belief; whereas we acknowledge that all things are from one God and through one God, they think there are as many gods as there are things.”

Yet scholars argue that Orosius could not have intended real pagans as his readers, since such invective would alienate them. Rather, the Historiae was more likely aimed at Christians unsettled by Rome’s sack, giving them arguments against pagan critics and reassurance of divine providence.

The narrative voice complicates matters further, sometimes appearing autobiographical. In Book 5 Orosius describes fleeing his homeland:

"No matter where I flee, I find my native land, my law, and my religion.

Just now Africa has welcomed me with a warmth of spirit that matched the confidence I felt when I came here.

At the present time, I say, this Africa has welcomed me to her state of absolute peace, to her own bosom, and to her common law - Africa...."

Yet this too serves the apologetic aim of portraying Christianity as a universal refuge. The result is a text marked by multiplicity—part history, part apologia, part breviarium—whose contradictions and shifting registers have long unsettled its reception. (In defiance of history. Orosius and the unimproved past, by Victoria Leonard)

Orosius gave his age a universal history shaped by Christian conviction, a narrative that turned calamity into proof of providence. However flawed by haste or partiality, the Historiae survived where many works of greater polish did not, carried by its usefulness, its association with Augustine, and its resonance with a world seeking meaning after Rome’s fall. In its pages, the past became a stage for divine judgment, and history itself a witness to faith.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: