I’m a Roman Empire Nerd: Spartacus back to Netflix is a Historical Nightmare

Netflix’s revival of Spartacus will thrill fans of gladiatorial drama. For history-minded viewers, though, the series remains a stylized fiction that recasts a fragmentary past into soap-operatic certainties.

Netflix is re-licensing Spartacus (Starz) after years away, with all seasons — including the prequel Gods of the Arena — slated to arrive on September 22, 2025 (U.S.). The window length isn’t confirmed, but the timing ensures a fresh wave of attention for a show famous for its stylized violence and operatic plotting. That renewed visibility is precisely why the historical claims deserve a sober review. A compelling series can still miseducate, especially when it wraps conjecture in the costume of authority.

Why This “Return” Matters

Spartacus himself is not a cipher invented for television. He is a real figure, attested by ancient authors, who led a large and frightening revolt during the Third Servile War (73–71 BCE). Yet virtually everything beyond that skeleton — his motives, internal debates, and personal relationships — lies in shadow. The show fills those gaps with modern, character-driven arcs that secure narrative momentum but sacrifice historical caution.

For Roman Empire Times readers, this is familiar ground. We have written before about Spartacus as a historical actor rather than a modern icon, tracing the revolt through the few sources that survive and acknowledging how many questions remain open. The Netflix return is an opportunity to underline that distinction again: an engaging screen myth versus an evidence-based reconstruction.

Sources: What We Actually Know

Our best accounts of the revolt come from Plutarch’s Life of Crassus and Appian’s Civil Wars. Both wrote in the second century CE — generations after the events — relying on earlier historians like Sallust and Livy whose relevant texts are largely lost. Even so, Plutarch and Appian agree on the basics: Spartacus was a Thracian who escaped from a gladiatorial school at Capua with dozens of others, gathered a heterogeneous army, defeated several Roman forces, and was finally crushed by Crassus, with Pompey entering late and taking credit for mopping up survivors.

The thinness of the ancient record is crucial. Plutarch and Appian sketch broad movements, not intimate portraits. We do not possess a diary, correspondence, or a detailed campaign log from the rebel camp. The series fills the lacunae with intrigues and relationships that make for good television but go well beyond what the texts support. Viewers should keep the hierarchy clear: Plutarch and Appian are primary narratives; modern dramatizations are imaginative interpolations.

That caution matters most whenever the show presents a character’s “true” motive or a decisive political meeting that left no historical trace. In the absence of contemporary testimony, such scenes are narrative devices rather than recoveries of fact.

The Caesar Problem

The series’ most conspicuous liberty is the insertion of a young Julius Caesar into the heart of the Servile War. On screen he is a schemer inside Crassus’s orbit, trading stratagems and close-quarters confrontations with rebels. It is a powerful way to link familiar names and to frame the revolt as a prequel to Caesar’s later career. It is also unsupported by the sources.

Neither Plutarch nor Appian places Caesar in the campaign against Spartacus. Caesar and Crassus will later share political history, but there is no textual evidence that Caesar acted as a fixer in Italy during the slave war. Modern encyclopedic summaries and scholarly overviews repeat this point: he lived during the revolt, certainly, but his participation is unattested.

The choice to weave Caesar into the plot is understandable as television — it tightens the narrative and raises the stakes — yet it blurs the line between documented involvement and invented proximity. For an audience learning the period primarily through the series, the risk of misremembering invention as fact is high.

Batiatus, the Ludus, and a Cliff that Never Was

The show’s Capuan ludus (gladiator school) is cinematic: a multi-level complex perched theatrically above a cliff, doubling as a stage for confrontations and private intrigues. The real ludus associated with the revolt belonged to a Roman named Lentulus Batiatus (a corruption of Vatia in some manuscripts). Ancient sources identify him as the lanista whose school Spartacus escaped. That is nearly the sum of what we can say with confidence about his establishment from the record.

Archaeology and social history suggest gladiator schools were integrated into urban fabrics or their immediate outskirts, not dangling over vertiginous drops. They were walled, regimented institutions designed to control valuable human property — trained fighters whose lives were capital assets. Television sets privilege dramatic sightlines and symbolic placement; history points to enclosed training yards, barracks, armories, and administrative spaces sized to the business of spectacle.

When viewers internalize the cliff-top ludus as “how it looked,” they carry away a false architectural memory. The genuine debate among historians concerns the organization, financing, and staffing of gladiator schools — questions the series occasionally nods at but rarely treats with rigor.

Gladiators: To the Death? Not So Fast

A central promise of Spartacus is ever-escalating bloodshed, suggesting that gladiatorial bouts were regularly fights to the death. Modern scholarship draws a more complicated picture. Trained gladiators represented significant investments. While mortal outcomes did occur, the “every match ends in slaughter” premise is misleading. Rulesets, referees, and promoter economics mattered; gladiators who entertained reliably were valuable and fought repeatedly across seasons.

Recent syntheses accessible to the general reader emphasize this nuance: ancient combat sports balanced drama with sustainability. Elite funerary spectacles or imperial caprice could tilt the scales toward higher lethality, but routine school-run shows depended on a roster that survived more than an episode. The series’ balletic carnage works as choreography; as evidence of standard practice, it distorts.

This matters because gladiators in the revolt (Spartacus, Crixus, Oenomaus) are often imagined as death-court veterans honed by constant lethal wins. The reality is closer to professional fighters with specialized training who could still die, but whose careers were designed to be repeatable.

Ethnicity, Names, and Anachronism

The series casts a wide net of characters to diversify its world, but in doing so it often reassigns ethnicities and names in ways that flatten the historical texture. A Carthaginian nicknamed “Barca,” for example, borrows resonance from Hamilcar’s family name even though Carthage had been destroyed in 146 BCE and “Barca” functions in the show mostly as shorthand for ferocity. Enomao (Oenomaus) appears in ancient sources as a Gaul, not the identity presented on screen. These shifts are creative choices; they are not transparent to viewers unfamiliar with the period.

None of this denies that the rebel force was ethnically mixed. Plutarch and Appian note Gauls and Thracians among core lieutenants and a swell of rural slaves and herdsmen joining as the revolt grew. The problem is not diversity but specificity: when familiar labels are imported for dramatic effect, they can harden into canonical “facts” in public memory.

The same applies to invented Roman politicians and household members whose interpersonal subplots drive the series. In a record as thin as ours, an extra consul or tribune with a complex backstory makes for pacing — but viewers should be told up front, as many historical dramas now do, that characters and events have been condensed or fictionalized.

A Revolutionary Icon — or a Survivor?

Modern culture prefers Spartacus as a proto-revolutionary who consciously aimed to abolish slavery across the Republic. That image is powerful and morally satisfying, but it is not what the sources assert. The texts vacillate between Spartacus seeking escape from Italy, tactical campaigns for supplies and leverage, and a late-stage bid to negotiate from strength. Whether he intended to march on Rome is disputed even in antiquity.

This difference is not pedantry. Portraying Spartacus as a programmatic liberator recasts the war as a teleological struggle whose endpoint is emancipation, rather than an opportunistic and evolving revolt against a brutal system. The series gains a coherent “cause” and clear character motivation; the history remains more uncertain and more tragic. A responsible way to watch the show is to grant the moral clarity it desires without attributing that clarity to the record.

Spartacus can be admired as a symbol without turning him into a 1st-century BCE abolitionist.

An illustration of Spartacus, by Gideon Slife. Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

Compressing Timelines, Inflating Intrigue

Television thrives on compression. Campaign seasons shrink, journeys collapse into montages, conspiracies converge in a single atrium. In Spartacus, this logic produces a constant churn of reversals and betrayals that suggests an omnipresent Roman deep state arrayed against the rebels. The sources present something messier: praetors sent with insufficient forces, consuls suffering defeats, and a Senate that only gradually recognizes the scale of the emergency before empowering Crassus.

Likewise, the progression from breakout to Alpine strategy to southern maneuvering spans months and involves multiple commanders. The show streamlines those phases to keep the ensemble cast in tight orbit, which heightens drama while erasing the administrative lag and logistical problems that plague any ancient campaign. The consequence is a near-constant “now or never” tone that substitutes for the stop-start pattern of ancient warfare.

There is nothing wrong with compression if it is labeled as such. Problems arise when compressed sequences are later remembered as literal chronology. For audiences using the series as a first primer on late Republican crisis management, the distortions are significant.

What the Show Gets Right (and Why It Still Misleads)

To be fair, the series does succeed in conveying the fear the revolt inspired. Roman elites were alarmed by a fast-growing, mobile army deep in Italy, and the political stakes for Crassus and, later, Pompey were real. The improvisational quality of early Roman responses is also broadly captured: the state underestimated the threat before shifting to more experienced commanders.

The material world of training, equipment, and improvisation is sometimes well observed — gladiators adapting tools into weapons, the use of local terrain, and the recruitment of rural laborers with animal-handling experience. None of that rescues the show from its larger inventions, but it explains why it can feel authentic at moments even when it is not.

For educators and historically curious viewers, this is an opportunity rather than a problem. A scene can spark an interest that drives someone to Plutarch, Appian, or modern syntheses. The danger is when the scene becomes the history.

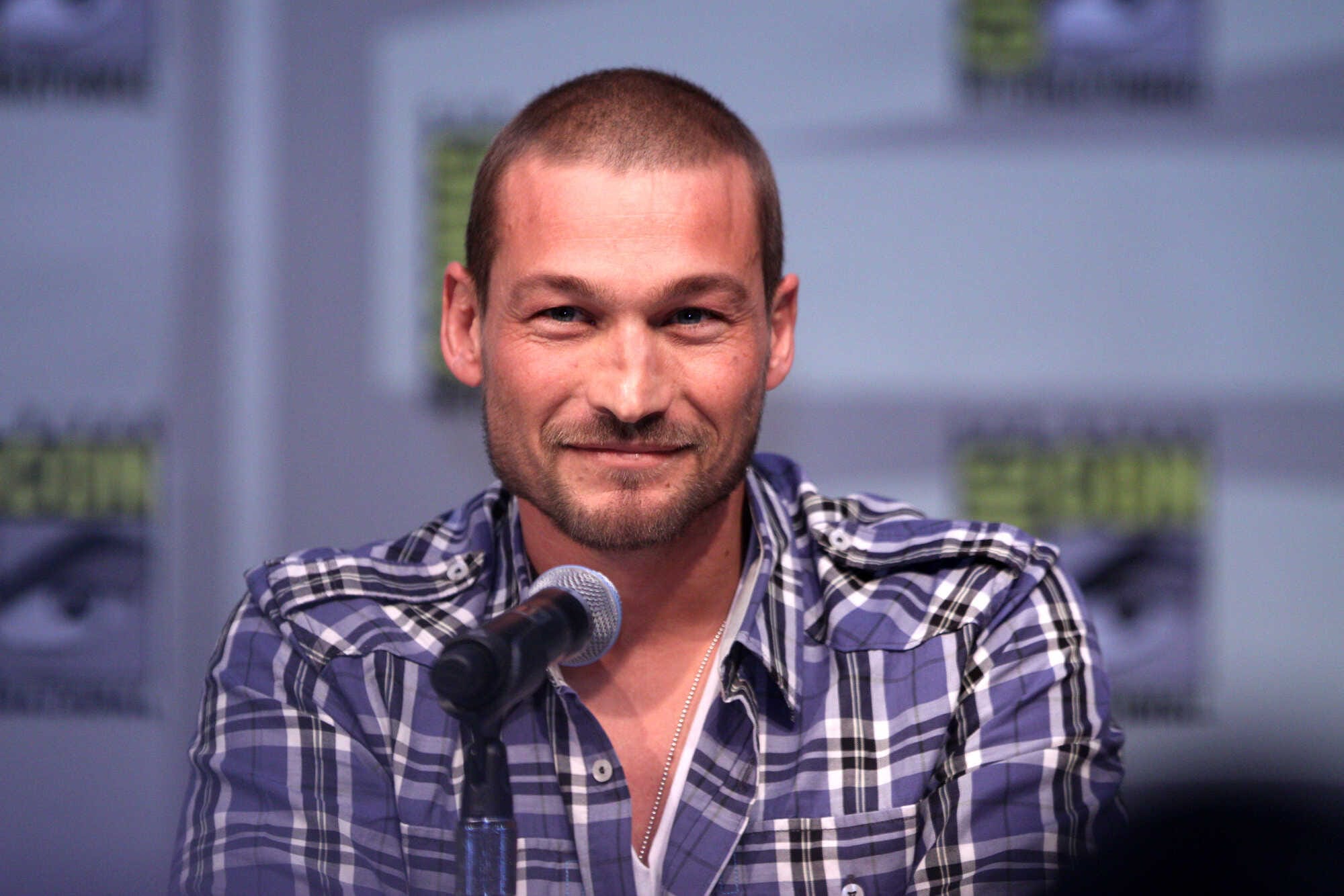

Image #1: Late actor Andy Whitfield speaking about Spartacus in Comic Con. Credits: Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 2.0 Image #2: Actress Lucy Lawless and Actor Liam McIntyre, speaking about Spartacus in Comic Con. Credits: Starz Entertainment, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Bottom Line: Watch, But Footnote It

The return of Spartacus to Netflix will introduce a new cohort to one of antiquity’s most gripping episodes. As entertainment, the series makes deliberate choices: center a charismatic lead, entwine him with marquee Romans, and escalate every fight to operatic stakes. As history, those choices blur boundaries that the ancient sources keep deliberately vague.

If you stream it, treat the show as historical fiction with aggressive liberties. Use it as an on-ramp to the texts that survive, and to the careful modern work that weighs them. Rome’s slave war does not need invented conspiracies or imported celebrities to be compelling. The fragments we possess, read with care, are dramatic enough.

The revolt of Spartacus deserves attention as a complex social uprising inside a slave society — not merely as a canvas for spectacle. Netflix can put the show back in front of us. We can put the record back beside it.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: