How Gaius Marius Changed Rome’s Armies Forever

Gaius Marius reshaped Rome’s war-machine. By opening enlistment to the capite censi, organizing legions by cohorts, lightening baggage—“Marius’ Mules”—and elevating the eagle, he turned a citizen militia into a professional army that outlived the Republic.

Gaius Marius (157–86 BCE) stands among the most transformative commanders of the ancient world. Under his leadership, Rome secured victories in North Africa and repelled a massive invasion of some 300,000 Germanic tribes pressing into Italy. The key to these successes lay in a set of five radical reforms that reshaped recruitment, training, and the very makeup of Rome’s legions.

By opening the ranks to new segments of society and standardizing their service, Marius turned the citizen militia into a permanent, professional army. This shift gave Rome a powerful instrument for conquest abroad and control at home, establishing a military model that endured for centuries. Yet these changes also carried profound consequences, undermining the stability of the Republic itself.

The Marian Reforms Under the Historian’s Lens

The Roman military left a deep imprint on nearly every dimension of Roman life, and few areas of study remain untouched by its presence. The impact of Marius’ reforms can be traced through a wide range of evidence that allows historians to reconstruct and assess the transformation of Rome’s armies after his time. Yet the nature, reliability, and usefulness of these sources vary considerably, leading to conflicting, inconclusive, and at times erroneous interpretations of what the reforms truly involved.

Many general works on the Roman army provide only a brief overview of Marius’ changes, offering little detail on the motivations behind them or their long-term effects. More specialized studies on infantry equipment, examine weapons, formations, and battlefield practices, which can shed indirect light on how the reforms reshaped the military. Illustrations based on ancient descriptions and archaeological finds supply useful visual context, though their accuracy is often limited by artistic interpretation.

Texts focused exclusively on Marius are rare, particularly in English, and tend to emphasize his political career over his military innovations. A further complication lies in the scholarly tendency to attribute almost any military development between 110 and 30 BCE to Marius without firm evidence. Such claims are often unreferenced and lack corroboration, highlighting the need for comparative analysis across different types of sources.

Any serious reconstruction of the Marian reforms must begin with the ancient texts. Sallust’s Jugurthine War and Plutarch’s Life of Marius remain the most substantial accounts, while scattered details can be found in Appian, Florus, Pliny, Orosius, and Frontinus, writing between the first and fifth centuries CE. Comparative insights into pre- and post-Marian military practice can be drawn from Polybius, Livy, Caesar, Josephus, and Vegetius.

Later historians such as Tacitus and Suetonius also provide valuable context on the military and political climate of the late Republic and early Empire, while grammarians like Festus preserve important terminology relevant to the reforms. Yet biases, gaps, and the temporal distance of these sources pose challenges.

Sallust, a supporter of Caesar who served under him, often portrays Marius in a favorable light while attacking the Senate, as in the speech he ascribes to Marius in 107 BCE. Plutarch, writing some three centuries later, relied heavily on partisan sources such as Sulla’s memoirs. Others, like Diodorus’ Histories, survive only in fragments, with much of the material on Marius lost.

Beyond literary evidence, additional sources enrich the picture. Inscriptions, military diplomas, and official lists from the imperial period provide first-hand glimpses into the life of soldiers shaped by Marius’ reforms. Monuments such as Trajan’s Column, the Altar of Ahenobarbus, and funerary reliefs supply visual comparisons between the pre- and post-Marian army.

Archaeological discoveries—including camps, coins, and weapons—offer tangible links to the organization and equipment of the legions, often proving more reliable than literary testimony. Together, these sources form the foundation for any reappraisal of Marius’ military reforms and their enduring impact on Rome.

The Roman army before Marius

To grasp the scale of Marius’ changes, it is essential to understand the structure of Rome’s army in the second century BCE. Polybius, writing in book six of his Histories, offers the fullest description. Each year, soldiers were selected by the dilectus, a ceremony of lot-drawing that filled four consular legions. Service was viewed as a civic duty, with enlistment originally lasting only a single campaign season, though by the Punic Wars terms of several years became common. Men could be recalled up to sixteen years of service, balancing soldiering with civilian life.

Eligibility depended on property. Only citizens worth more than 4,000 asses could serve, based on the belief that landholders would fight more loyally for the state. Recruits were then divided by wealth and age into four ranks: velites (light infantry skirmishers), hastati (young, medium infantry), principes (experienced heavy infantry), and triarii (older heavy infantry with spears).

Each was differently armed, from the lightly equipped velites with javelins to the heavily armed triarii. Though many scholars assume soldiers supplied their own equipment, Polybius and Plutarch indicate that the state issued arms, with costs deducted from pay. Wealth distinctions may therefore have reflected repayment ability rather than direct purchase.

A legion numbered around 4,200 men, divided into maniples and centuries, arrayed in three successive lines of hastati, principes, and triarii. This “manipular” system allowed units to rotate in and out of battle: skirmishers began the fight, hastati engaged next, then principes, with the triarii as the final reserve. This flexible deployment was effective against rigid phalanxes but left gaps that could be exploited by looser formations. It was in this army, organized by wealth and fought in layered ranks, that Marius began his career—an army he would soon revolutionize.

The Military Career of Gaius Marius

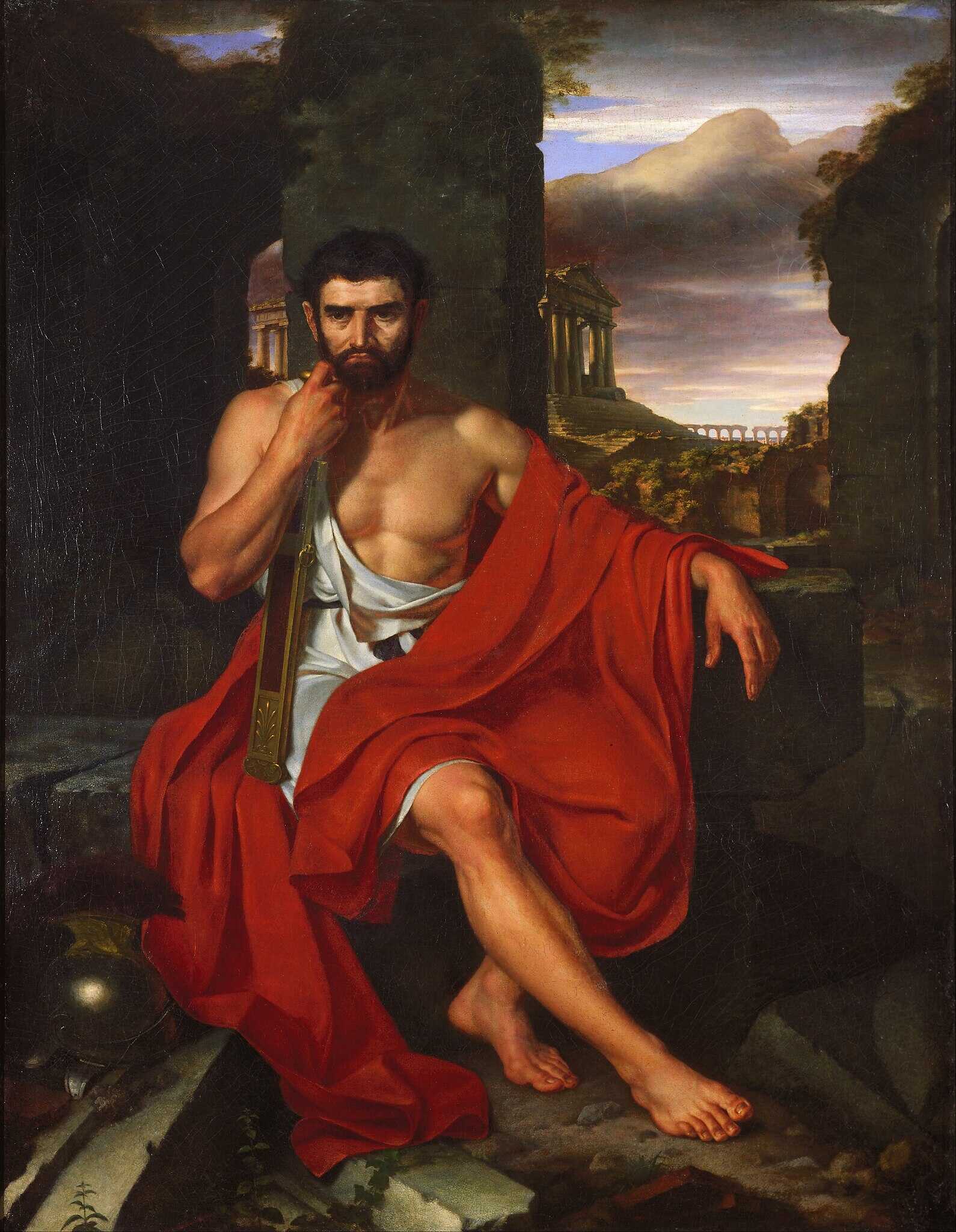

Understanding the reforms of Gaius Marius requires first setting them against the backdrop of his career. Born near Arpinum in 157 BCE to modest parents, Marius came from outside the Roman aristocracy and sought advancement through military service. His career began in 134 BCE as a cavalryman in Spain under Scipio Aemilianus. He later held a tribunate in the 120s BCE, served in Asia Minor, and was elected praetor in 115 BCE, followed by a governorship in Spain the next year.

In 111 BCE Rome went to war with Jugurtha of Numidia, a conflict prolonged by broken truces, revolts, and Roman setbacks. By 109 BCE Quintus Caecilius Metellus commanded in Numidia, with Marius as his cavalry officer. After several inconclusive campaigns, Marius secured election to the consulship of 107 BCE with popular backing and replaced Metellus in command.

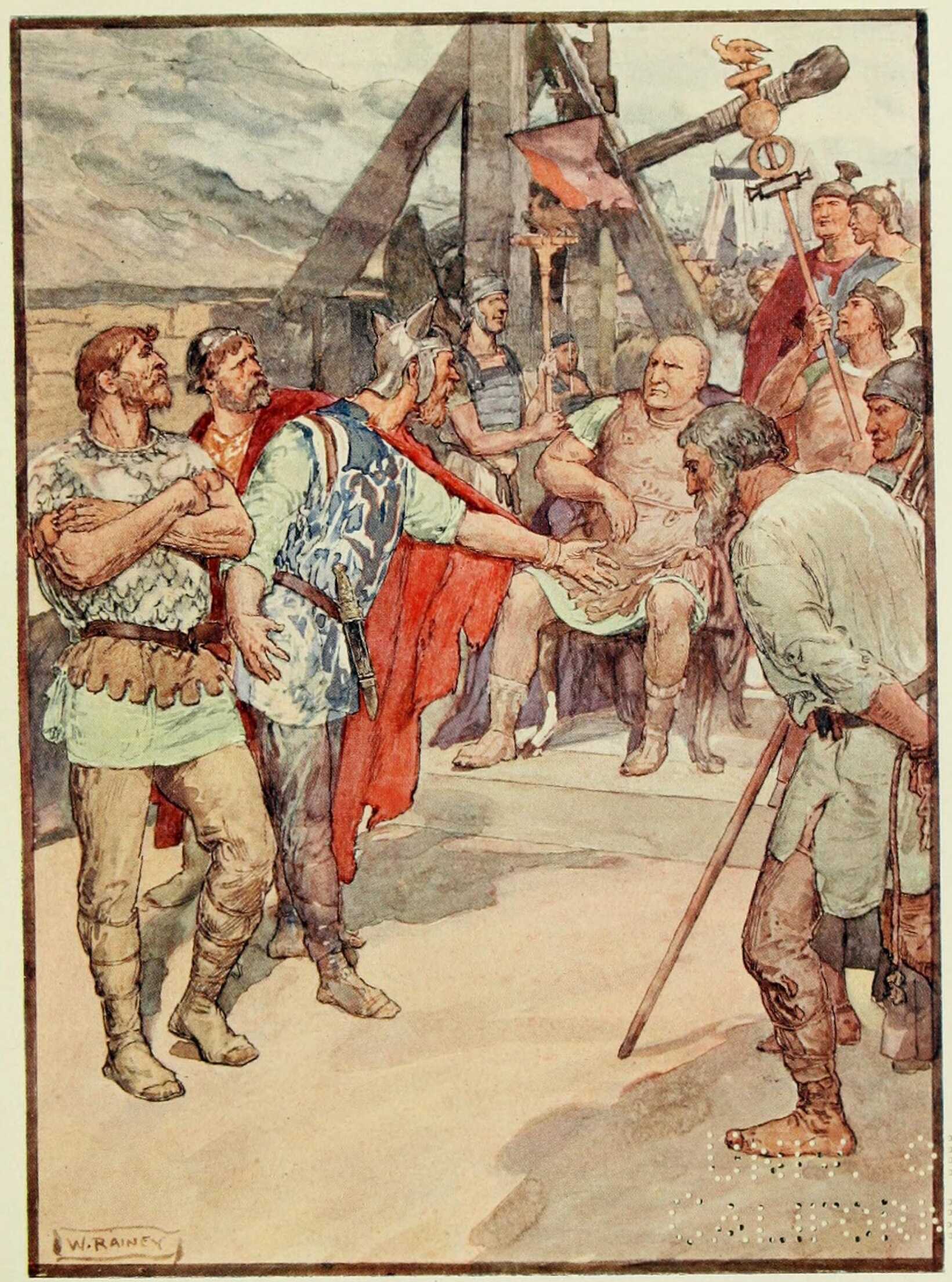

It was here that he introduced his first reform: allowing citizens without property to enlist. His campaign brought mixed results, but by 106 BCE he had taken several cities and Jugurtha’s treasury, aided by cavalry under Lucius Cornelius Sulla. The war ended in 105 BCE when Jugurtha was handed over through negotiations with Bocchus of Mauretania.

With Jugurtha defeated, Marius was elected consul again in 104 BCE to face a far greater challenge: migrating Germanic tribes who had annihilated a Roman army at Arausio. As he raised new troops, Marius introduced three linked reforms: altering the baggage train and the soldiers’ load, making the cohort the army’s basic unit, and adopting the eagle as the sole legionary standard. While the German tribes first diverted toward Spain, Marius held repeated consulships in 103 and 102 BCE to prepare.

In 102 BCE the Teutones and Ambrones advanced into southern Gaul, while the Cimbri and Tigurini threatened northern Italy. Marius defeated the Teutones and Ambrones at Aquae Sextiae after securing supply lines with a new canal, then joined his colleague Catulus against the Cimbri. Before the decisive battle at Vercellae in 101 BCE, during his fifth consulship, Marius introduced his final reform: a redesign of the legionary javelin. At Vercellae, the combined armies of Marius and Catulus crushed the Cimbri, ending the Germanic threat.

The Teutones: A large tribe often mentioned alongside the Cimbri. Ancient writers describe them as formidable warriors, feared for their size and ferocity. Their migration brought them into conflict with Rome after they crossed into southern Gaul.

The Ambrones: A smaller but allied tribe, culturally and linguistically related to the Teutones. They fought alongside them during the invasion of southern Gaul. Ancient sources, such as Plutarch, note their distinctive war cries — shouting “Ambrones!” as they charged into battle.

In 102 BCE, these two tribes advanced toward Italy but were intercepted by Marius at Aquae Sextiae (modern Aix-en-Provence, France). There he won a decisive victory, annihilating the Ambrones and most of the Teutones, an achievement that bolstered his reputation as Rome’s savior.

The rest of Marius’ life was marked less by triumph than turmoil. He returned to politics with diminishing success, clashed with the Senate over land for his veterans, and entered into bitter rivalry with Sulla over command in the East. He still fought in the Social War of 90–89 BCE, but the conflict with Sulla led to civil war, executions, and his exile.

Restored to power in 86 BCE, he was elected consul for a seventh time, only to die seventeen days later at the age of seventy-one. No further reforms followed his earlier innovations, but the army he had reshaped endured long beyond him.

Opening the Ranks: Marius’ Head-Count Reform (107 BCE)

In 107 BCE, while preparing for the war in Numidia, Marius broke with tradition by enlisting volunteers from the capite censi—landless citizens normally exempt from legionary duty—and recalling veterans to fill his ranks. This marked a decisive departure from the dilectus, which had long limited service to property holders.

Scholars have debated whether this was the “next step” in a gradual reduction of property thresholds or a radical reform. The evidence suggests the latter: Marius faced not a shortage of men in general, but a shortage of willing property-owning recruits, reluctant to endure a long and unprofitable African campaign. Volunteers from the head-count offered a solution—men with little to lose and much to gain from military pay, plunder, and the chance of advancement.

The consequences reached far beyond Numidia. By opening the army to the dispossessed, Marius shifted loyalty from the Republic to individual commanders who provided success and rewards. This reform gave Rome a larger and more flexible pool of manpower, laying the groundwork for the professional armies of the late Republic and the Principate. It also set in motion a new political dynamic where military power became the key to political office—a path later taken by Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar.

From Manipules to Cohorts

In the late Republic, Rome abandoned the manipular system in favor of the cohort, reshaping the army’s structure and battlefield tactics. Before Marius, cohorts existed as ad hoc groupings of maniples, but evidence suggests that around 104 BCE, during preparations for the Germanic wars, Marius formalized the cohort as the legion’s basic unit. Each cohort now contained six centuries of eighty men—about 480 soldiers—ten cohorts forming a legion.

This change erased the old class-based divisions of hastati, principes, and triarii. Uniform equipping replaced varied weaponry, with all legionaries now carrying the gladius, scutum, and pila. Removing light-armed velites and standardizing arms created formations better suited to withstand the mass charges of the Cimbri and Teutones. The cohort also gave flexibility: units could form defensive squares, shift to meet attacks from several directions, and mutually support each other.

Beyond tactics, the cohort strengthened cohesion. Mixing recruits from all backgrounds in one formation, outfitted alike, built solidarity and reduced resentment. Marius’ recall of veterans further stabilized these new units, while the cohort’s larger size made them more resilient in melee. The adaptability and esprit de corps fostered by this reform ensured that the cohort became the permanent backbone of the Roman legion, retained through Caesar’s time and into the Empire.

Maniple vs Cohort at a Glance

Manipular Legion (pre-Marius)

Basic Unit: Manipulus (“handful”)

Unit Size: 120 men (hastati & principes) or 70 men (triarii)

Legion Size: ±4,200 men (plus cavalry & allies)

Troop Types: Divided by weather/age: velites, hastati, principes, triarii

Equipment: Varied by class: from light javelins to spears and heavy armor

Deployment: Triplex acies (three lines), maniples staggered in checkerboard

Tactical Strengths: Flexibility against phalanx-style armies, rotation of ranks

Loyalty & Cohesion: Based on property class and civic duty

Cohort Legion (post-Marius)

Basic Unit: Cohors (“enclosure, band”)

Unit Size: ±480 men (6 centuries of 80)

Legion Size: ±5,000 men (10 cohorts)

Troop Types: All legionaries equipped and trained alike

Equipment: Standarized: gladius, scutum, pila for all

Deployment: Cohorts as flexible blocks; could form squares, pivot, support each other

Tactical Strengths: Greater cohesion, resilience, and adaptability vs large tribal warbands

Loyalty & Cohesion: Built through uniform training, shared arms, and mixed recruitment

Marius’ Mules: Mobility, Endurance, and the Transformation of Roman Warfare

In 104 BCE, during preparations for the Germanic threat, Marius introduced one of his most enduring reforms: reducing the baggage train and requiring each legionary to carry his own kit. Soldiers bore rations, cookware, tools, and weapons on a forked pole across their shoulders, earning the nickname “Marius’ Mules.” While earlier commanders like Scipio Aemilianus and Metellus had experimented with burdening troops for discipline, Marius institutionalized the practice.

The reform had sweeping effects. By shrinking the reliance on cumbersome wagons and animals, the legions gained mobility, speed, and independence. Units could march faster, seize ground, and entrench themselves without waiting for supplies. This meant Rome’s armies could advance deep into hostile territory, conduct rapid strikes, and adapt to sudden encounters.

Caesar’s later campaigns in Gaul vividly demonstrate the tactical freedom this system provided: troops in “light order” could march ahead of baggage, fortify a base, and fight effectively.

Beyond logistics, the hardship of carrying heavy loads hardened soldiers physically and forged a new esprit de corps. Shared endurance promoted solidarity and discipline, while the ability to live off what they carried made legions less tied to the state’s traditional structures. This self-sufficiency became a hallmark of the Roman soldier. Evidence from Josephus, Trajan’s Column, and Vegetius confirms that the system persisted well into the Empire, proving its long-term value.

“Marius’ Mules” turned the legion into a faster, more mobile, and more cohesive fighting machine. It was not simply a change in marching order but a redefinition of how Rome waged war—projecting power swiftly, decisively, and with armies bound together by shared burden. It remains one of the most important logistical revolutions in Roman military history.

What Did a Gaius Marius “Mule” Carry?

A Marian legionary typically bore 30–40 kg of equipment on a forked carrying pole (furca). His load included:

- Weapons → Gladius (short sword), pila (two javelins), dagger

- Armor & Shield → Helmet, mail or breastplate, large scutum shield

- Rations → Grain (about two weeks’ supply), dried foods, water flask

- Cooking gear → Pot, pan, and basic utensils

- Tools → Entrenching spade or pickaxe, saw, and stakes for camp palisade (sudes)

- Personal kit → Cloak, blanket, spare sandals, and small personal item

The Eagle, the eternal symbol of the Roman army

Among Rome’s most iconic military emblems stands the eagle, though this was not always the case. Before Marius, legions carried several animal standards, including the wolf, horse, boar, and minotaur. Pliny the Elder, the only ancient author to attribute the reform directly to Marius, dates it to his second consulship in 104 BCE. Pliny associates the eagle with the prima ordinatio, while the other animals were linked to different ranks.

Scholars remain divided over how these standards functioned: some think each consular legion carried one of the four animals, others believe the manipular ranks each had their own insignia. A closer reading of Pliny, however, suggests that legions carried all five standards together but only took the eagle into battle, leaving the others in camp. The eagle, under the care of the aquilifer and the senior centurion of the first cohort, thus already symbolized the legion as a whole.

“Before the time of Gaius Marius, the legions carried five standards: the eagle, wolf, minotaur, horse, and boar. Marius gave preeminence to the eagle, and it alone began to be carried into battle, the rest remaining only in camp.”

Pliny, Natural History 10.16

Marius’ reform abolished the use of the four lesser standards, leaving the eagle as the sole emblem of the legion. This aligned naturally with his wider restructuring: the end of class-based ranks, the adoption of the cohort, and the uniform equipping of troops. Older standards such as the vexillum and open-hand manipular signs may have continued as banners for centuries, but their role became secondary.

The aquila was placed with the first cohort, usually on the right flank, serving as the reference point for deployment. Standard-bearers of cohorts and centuries aligned themselves by it, ensuring cohesion in movement and battle. Caesar’s order at Ruspina—that men should not advance more than four feet beyond their standards—illustrates this practical function.

The eagle quickly became more than a tactical marker. It created esprit de corps, binding together men of varied backgrounds who had joined the army as volunteers after the head-count reform. Loyalty, once tied to property and the Republic, now centered on the legion and its eagle. Studies of military cohesion show that unit identity is crucial to morale, and for Roman soldiers the aquila embodied their collective pride.

Caesar’s campaigns provide examples of aquilifers who risked or gave their lives to save the eagle, even throwing it into enemy ranks to spur comrades forward or carrying it ashore in Britain to force hesitant soldiers to follow. Accounts describe soldiers defending standards to the death, and Tacitus later called the eagles the “true deities of our legions.”

The eagle also carried religious meaning. Associated with Jupiter, its thunderbolt grasp confirmed the legion’s tie to Rome’s supreme god. This gave soldiers the sense of marching under divine protection, while offering Rome a potent symbol of its claim to rule. Ancient sources even describe standards “refusing” to be moved, such as before Crassus’ disaster at Carrhae, when the eagles seemed to resist crossing the Euphrates. These stories reflect the semi-divine aura that had come to surround them.

By the late Republic and into the Principate, the eagle’s political significance grew. Cinna carried one of Marius’ old eagles during the Marian War, and smaller eagles appear in Caesar’s armies. Under Augustus, eagles became instruments of diplomacy and propaganda. Envoys swore oaths before them, cities adopted their image, and Herod himself set up a golden eagle at the Jerusalem Temple.

Victories and defeats were measured by standards captured or recovered: Augustus gloried in regaining those lost by Crassus to the Parthians, a feat advertised on coins and monuments, while the loss of three eagles in the Teutoburg disaster was remembered as a profound humiliation.

In the end, the adoption of the eagle as the sole legionary standard reshaped Roman identity. It gave legions unity, pride, and a divine connection; it provided the state with an emblem to project its authority abroad; and it created a symbol so powerful that its fate was tied to the legion itself. Through this reform, Marius left one of his most enduring legacies—an image that would stand at the heart of Rome’s military and imperial power for centuries.

The Pilum: Marius’ Last Reform

The pilum was Rome’s heavy throwing spear, central to legionary tactics. Traditionally it had a wooden shaft and long iron shank, fixed with two rivets. Marius altered its design before the battle of Vercellae (101 BCE): one iron rivet was replaced by a wooden peg that snapped on impact, bending the shaft and rendering enemy shields useless. Ancient writers, especially Plutarch, highlight its success in forcing the Cimbri to abandon their shields.

Scholars debate the effectiveness and longevity of this innovation. Archaeological finds show pila of different designs, some with iron soft enough to bend, suggesting multiple experiments to ensure shields became unusable. Caesar later describes pila that bent at Bibracte in 58 BCE, showing the principle endured even if Marius’ exact peg design did not.

The pilum reform was not as permanent as his other changes—the cohort system, “Marius’ Mules,” or the eagle—but it reflected the same spirit of adaptation. It showed Marius’ focus on practical battlefield needs, ensuring that Rome’s legions had every advantage over massed tribal armies. While the rivet modification was eventually abandoned, the pilum itself remained a defining weapon of Rome’s soldiers into the imperial era. (On the Wings of Eagles. The reforms of Gaius Marius and the creation of Rome’s first professional soldiers, by Christopher Anthony Matthew)

Marius’ reforms were born of hard necessity but forged a new kind of Roman army—mobile, cohesive, and increasingly tied to its commanders. That force secured Rome’s borders and fueled expansion; it also unsettled the Republic’s politics. Whatever the debates over detail, the army that marched into the last century of the Republic—and the Empire that followed—moved in Marius’ footprint.

The Roman Army Before and After the Marian Reforms

Pre-Marian Army (Polybius’s manipular system)

Recruitment: Limited to citizens worth ≥ 4,000 asses; militia drawn annually via dilectus

Service Term: Seasonal or campaign-based; could total 16 years across life

Motivation: Civic duty tied to property ownership

Organization: Manipular system: velites, hastati, principes, triarii ranked by wealth & age

Equipment: Varied by class/wealth; partly issued by state, repaid via wages

Unit Strength: ±4,200 per legion; maniples of 60-120 men

Tactics: Triplex acies with successive ranks; maniples allowed rotation & flexibility

Loyalty: To Republic and Senate; soldiers as citizen-militia

Post-Marian Army (Reforms 107-104 BCE)

Recruitment: Open to all Roman citizens, including landless capite censi volunteers

Service Term: Long-term service (ca. 16-20 years), creating standing armies

Motivation: Career path with pay, equipment, and potential land grants

Organization: Cohort system: 10 cohorts per legion, each 480 men; class divisions abolished

Equipment: Standardized equipment for all, uniform appearance across legion

Unit Strength: ±5,000 per legion; cohorts of 480 men, 6 centuries each

Tactics: Cohorts provided larger, more versatile blocks; could form defensive squares, adapt formations

Loyalty: Increasingly personal loyalty to commanders who paid and rewarded them

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: