Titus and Domitian: Brotherhood on Rome’s Imperial Stage

Ancient writers cast Titus and Domitian as rival brothers, with the younger plotting against the elder. Inscriptions, coins, and monuments, however, reveal a dynasty that publicly honored unity, complicating the image of fraternal enmity.

The new Peacock series Those About to Die featuring on Amazon Prime, paints Domitian as a schemer, lurking in the shadows of his brother Titus, ever eager to seize the purple. Jealousy, ambition, and betrayal drive the on-screen drama—but how much of this reflects reality?

Ancient writers often portrayed rivalry between the Flavian brothers, even hinting that Domitian plotted against Titus. Yet modern historians caution that such stories owe as much to senatorial hostility toward Domitian as to the uncertain truth of their relationship.

The Children of Vespasian

The long-standing negative image of Domitian, shaped by both senatorial and Christian traditions, has been undergoing vigorous reconsideration in recent decades. Scholars have increasingly questioned the reliability of post-Domitian accounts such as those of Pliny, Tacitus, and Suetonius, though doubts remain about how far one can go in attempting to “rehabilitate” the last Flavian ruler through selective reinterpretation of literary anecdotes.

A more fruitful approach, recent studies suggest, is to read these literary sources alongside newly examined epigraphic and archaeological evidence. The debate over Domitian is ongoing, which is hardly surprising given the volume and diversity of surviving sources.

Contemporary writers such as Statius, Martial, Frontinus, and Quintilian often presented him in a favorable light, while later works written after his assassination in 96 CE—Pliny’s Letters and Panegyric, Suetonius’s Lives of the Caesars, and Tacitus’s Agricola and Histories—are consistently hostile. Earlier generations of scholars tended to echo this hostile tradition, which consistently darkened Domitian’s principate in order to celebrate the “golden age” of Nerva and Trajan. Pliny himself declared:

“the first duty of good citizens towards a perfect emperor is to attack those who are not like him. Indeed no one can love good emperors who does not hate the bad ones enough”

Panegyric 53.2–3

Modern scholars, however, caution against both extremes. Some note that rhetorical tropes and exaggerations are natural to certain genres, but that does not make the ancient sources either wholly unreliable or wholly accurate. More recently, scholars have warned that anti-Domitian sources should not be dismissed simply as products of Antonine propaganda, and that very different works like Pliny’s Panegyric, Tacitus’s Histories, and Suetonius’s Lives should not be read as if they shared a uniform agenda.

In light of these issues, new attention has turned to the material evidence of Domitian’s reign, which has grown significantly in both quantity and understanding. While fragmentary and often official in character, inscriptions and archaeological remains can shed light on Domitian’s rule and the narrative strategies used by Nervan and Trajanic authors to cast it as a “reign of terror.”

The Suetonian Life of Domitian in particular helped embed a hostile image of the emperor, but the extent to which this aligns with reality is questionable.

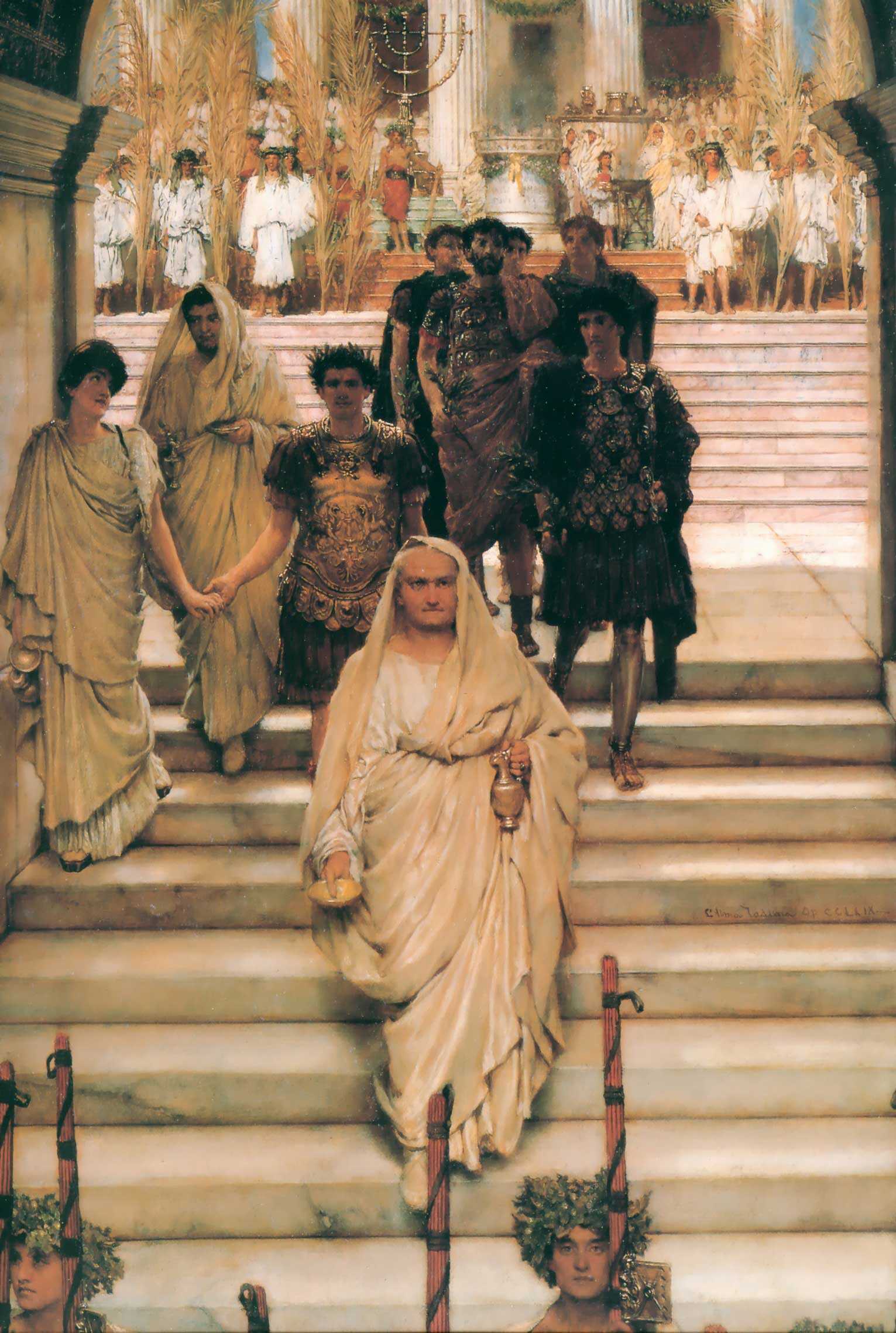

Emperor Domitian painting, by Abraham Bloemaert. Public domain

Key accusations—such as his alleged desire to be called “Master and God” and his supposed incestuous affair with his niece Julia—require closer scrutiny when set against the available evidence. Ultimately, a more holistic reading that brings together literary and material sources offers a cautious but clearer picture of Domitian’s principate and the processes that shaped its memory.

Suetonius and the Shaping of a Tyrant

Written about thirty years after Domitian’s death, Suetonius’s Life of Domitian is one of the most influential accounts of the Flavian age. With Tacitus’s Histories and Dio’s Roman History surviving only in fragments for this period, Suetonius provides the fullest surviving narrative of Domitian’s reign and the only continuous treatment of the Flavian dynasty.

For a long time, his version was regarded as more trustworthy than the openly hostile writings of Pliny and Tacitus. Modern scholarship has increasingly shown that Suetonius too shaped his material to portray Domitian as a tyrant.

Many of his characterizations rely on commonplaces drawn from Aristotle’s descriptions of tyranny, the same motifs applied to emperors such as Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero. His narrative, composed under Hadrian, develops around three major themes: Domitian’s enmity with his brother Titus, reckless financial policies, and cruelty.

These were not new inventions but refinements of accusations already suggested, though more indirectly, by Pliny and Tacitus. Suetonius organized them into coherent, morally charged stories that became the standard framework for later depictions of Domitian. On the fraternal theme, Suetonius casts Domitian in sharp contrast to his elder brother. He writes that Domitian strove:

“to match his brother’s power and fame”

and that he:

“did not cease plotting against his brother, either secretly or openly”

Later, after Titus’s death, Domitian is said to have honored him with deification alone, while in practice he:

“accorded him no honor except that of deification, and often attacked him with indirect speeches and edicts”

By contrast, Titus appears as the generous sibling who used his wealth for the public good. Yet, inscriptions complicate this picture.

Suetonius presents Domitian’s building program as motivated by vanity and greed, in contrast to Titus’s generosity. But epigraphic evidence shows that Domitian too used his own funds to rebuild after the fire of 80 CE, continuing Flavian family policy rather than erasing predecessors for his own glory.

In Suetonius’s hands, Domitian becomes a “new Nero,” his supposed cruelty rationalized and his memory darkened through contrast with Titus’s positive model. The result is a carefully crafted narrative that reinforced the hostile tradition, even as material evidence offers a more complex view.

Domitian and Titus: Rivalry, Rumor, and the Evidence of Memory

A recurring theme in ancient accounts is the supposed hostility between Domitian and his elder brother Titus. Tacitus in the Histories already hints at tension, noting Domitian’s exclusion from power and alluding to suspicions of conspiracy against his brother. Pliny speaks as though this rivalry was accepted fact, remarking that someone:

“as a friend of Domitian he feared Titus”

Letters 4.9.2

Material and epigraphic evidence, however, complicates this story. Suetonius claims that Domitian received only one ordinary consulship in 73 CE thanks to Titus stepping aside, presented as an act of brotherly kindness that emphasized Titus’s love and Domitian’s ingratitude. Yet the fasti consulares, confirmed by an inscription from that year (CIL V 7239), show a pattern: the Flavians rotated the consulship on a two-year cycle to share honors within the family and their allies.

In 71, Vespasian and Nerva gave way to Domitian and Cascus; in 72, Titus was consul with Vespasian; in 73, Domitian and Messalinus held the office; in 74, Titus resumed it with Vespasian. Far from being a special concession by Titus, Domitian’s full consulship appears part of an established system of Flavian power-sharing.

Despite this, Suetonius’s portrayal became influential. Later writers exaggerated the narrative of fraternal enmity, culminating in Cassius Dio’s dramatic account that Domitian placed the dying Titus in a basket of snow to hasten his end. According to Dio, Titus regretted only that he had:

“loved too much his ungrateful brother”

Suetonius also downplayed Domitian’s commemoration of Titus. He suggests Domitian’s honors were tokenistic, comparable to Nero’s neglect of the cult of Claudius. He says Domitian pretended grief:

“pretending to love his brother and mourned him and uttered his eulogy in tears and wanted him divinised, pretending precisely the opposite of what he really desired”

Cassius Dio 67.2.6, paraphrasing Suetonius

In this comparison, Domitian is implicitly likened to Nero, contrasted with the positive model of Titus. Yet the material record tells another story.

Unlike Claudius’s neglected cult, Titus’s deification under Domitian was substantial. Monuments such as the Temple of the Flavian Family (Templum Gentis Flaviae), the Arch of Titus, the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, and the Porticus Divorum all honored him.

Inscriptions from Rome and the provinces attest to the cult of Divus Titus. The Senate itself dedicated an inscription, while another from 81 CE, commemorates him as a divine figure. Domitian’s coinage also celebrated Titus, issuing multiple types with his portrait between 81 and 83 CE.

While Suetonius and Pliny cast Domitian as begrudging and insincere, the archaeological and numismatic evidence suggests that at least at the level of official representation, Domitian honored his brother and fostered his cult. The literary tradition shaped Domitian into a “new Nero,” but the monuments and inscriptions show a dynasty presenting unity and reverence, even if the private relationship between the two brothers can never be fully known. (Un-damning Subplots: The Principate of Domitian Between Literary Sources and Fresh Material Evidence, by Tommaso Spinelli and Gian Luca Gregori)

Was Domitian Truly Sidelined?

Later tradition often described Domitian as a frustrated younger son, kept in the shadows by his father and brother. Yet the evidence points in another direction. During Vespasian’s reign he held several consulships, along with priesthoods and public honors that marked him as a recognized part of the dynasty. Far from being excluded, he was woven into the Flavian succession plan, even if Titus was always the heir-apparent.

Some tales of tension do not withstand scrutiny. Tacitus claimed that Titus once begged Vespasian to spare his younger brother, but this story has all the signs of invention. The familiar theme of brothers locked in enmity—so often applied to later imperial pairs such as Caracalla and Geta—colored Domitian’s image in the same way.

The reality seems more measured. Coinage and official honors repeatedly linked Domitian with his brother, suggesting association rather than exclusion. What survives from the Flavian program does not reveal a prince frozen out of power, but one included in the dynasty’s public face. (The character of Domitian, by K.H Waters)

Was Domitian Responsible for the Death of Titus?

The two Flavian brothers were divided from the start. Titus was eleven years older, raised in the imperial court beside Britannicus, and later absent on military campaigns, especially in Judaea until 71 CE. Domitian, left in Rome, grew up largely without him. They “hardly knew each other,” and this early distance helps explain why no strong bond was ever forged.

Later gossip claimed Titus sought to slight Domitian through office appointments. One story had Titus granting a consulship to Aelius Lamia, the former husband of Domitian’s wife, as if to humiliate him. Another claimed he promoted Sabinus IV as consul for 82 to keep Domitian in check. Both collapse under scrutiny.

In truth, Titus had planned to share the consulship of 82 with his brother — a sign of unity at the very height of power. Only Titus’s sudden death in September prevented it, and Sabinus filled the vacancy afterwards.

At the moment of transition, Domitian acted decisively. He hurried to the praetorian camp, promised a donative, and was acclaimed emperor. The Senate, however, first gathered to honor Titus, delaying Domitian’s formal recognition until the following day. That hesitation fed the rumors of intrigue and suspicion that colored his accession, although there was no proof he was responsible for the death of his brother. (The Emperor Domitian, by Brian W. Jones)

The relationship between Titus and Domitian remains elusive, glimpsed only through hostile traditions and fragmentary evidence. Ancient authors loved the story of jealous brothers, turning Domitian into a schemer against the generous Titus.

Yet coins, inscriptions, and monuments show a dynasty projecting unity, and modern scholarship has exposed the literary patterns that shaped the darker image. Whether their private bond was strained or not, what survives is a tale of how rivalry was written into history, and how the truth still lies somewhere between suspicion and ceremony.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: