Claudius the Unexpected: The Emperor They Never Saw Coming

Dismissed as unfit to rule, Claudius stunned Rome by becoming one of its most capable emperors—expanding borders, reforming government, and ruling with quiet competence.

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus was never meant to rule. Born into the Julio-Claudian dynasty, he lived much of his life in the shadows—dismissed by his own family as weak, mocked for his stammer and limp, and denied the public roles expected of a Roman noble.

Yet in a twist that stunned the empire, Claudius became emperor in 41 CE, plucked from hiding by the Praetorian Guard after the assassination of Caligula. Far from the puppet emperor imagined by ancient historians, Claudius would go on to govern with surprising skill, expanding Roman territory, reforming imperial administration, and reshaping what it meant to wield power in the early empire.

Dismissed, Overlooked—Then Crowned

Tiberius‘s father, Drusus, had died young; his brother Germanicus was a hero of Rome and presumed heir to the principate. But when Germanicus died in 19 CE, the question of succession passed not to Claudius but to Germanicus’s sons—among them, the future emperor Caligula.

From the outset, Claudius was marked by what his contemporaries considered deformities: a limp, a stammer, and other physical traits that suggested to his family a mind unfit for public life. His own mother dismissed him with contempt, reportedly calling him “a monster of a man, one that Nature had only begun to form.”

In a society that prized rhetorical eloquence, martial vigor, and political visibility, Claudius was kept away from military command and public office.

Emperor Claudius, as Jupiter Capitoline. Credits: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Augustus passed him over for promotion, and Tiberius confined him to the margins of imperial life. Claudius spent these years in study, quietly composing histories of the Roman Republic, the Etruscans, and even Carthage, while being excluded from Rome’s most vital institutions.

And yet, in 41 CE, following the dramatic assassination of Caligula, Claudius was thrust into power. Hiding in the palace, fearing for his life, he was discovered by a Praetorian Guardsman and declared emperor. The Senate had not chosen him. Neither had the people.

But through the power of the military and sheer dynastic presence, Claudius ascended to rule the Roman world. While ancient authors like Suetonius, Tacitus, and Dio Cassius portrayed Claudius as weak-willed, easily manipulated by wives and freedmen, and far from a commanding figure, other sources tell a different story.

Inscriptions, coinage, official decrees, and monuments reveal an emperor deeply concerned with legitimacy, civic order, and imperial continuity. Through these materials, Claudius emerges not as the passive figure of literary caricature, but as a ruler who actively used public communication to reinforce his authority.

Claudius’s rule cannot be understood solely through the lens of Rome. His policies and public image extended deep into the provinces, particularly in Gaul and Britain, where he sought to engage not just with the elite, but with local communities across the empire.

His reign proved pivotal in the evolution of the Principate after Augustus—not as a passive continuation, but as a moment of reinvention. Claudius expanded Rome’s borders, reformed its institutions, and subtly redefined the image of imperial leadership.

Far from being hindered by his physical impairments or unconventional path to power, Claudius may have succeeded precisely because he offered a different kind of authority—one rooted in stability, administrative clarity, and careful image-making. His story invites a deeper reflection on what truly counted as strength in the Roman imperial system—and on who, in the end, was best suited to govern it. (Claudius Caesar: Image and Power in the Early Roman Empire, by Josiah Osgood)

From Madness to Order: Caligula’s Fall and Claudius’s Rise

Throughout its long history, the Roman Empire saw emperors who were builders of order and vision—Octavian, Trajan, Hadrian, Constantine, and Marcus Aurelius remain enduring names of military skill, philosophical depth, and political foresight. But alongside these titans stood others who became infamous for their cruelty or indulgence. Among them, none cast a darker shadow than Gaius—known to posterity as Caligula.

When he came to power in 37 CE, expectations for the young prince were high. In his early months, he ruled with justice and dignity. But a sudden illness altered the course of his reign. What followed was a descent into extremes that shocked even Roman sensibilities: public appearances dressed as deities, accounts of incest and ritualized violence, and a cult of personality that blurred the line between theatrics and tyranny.

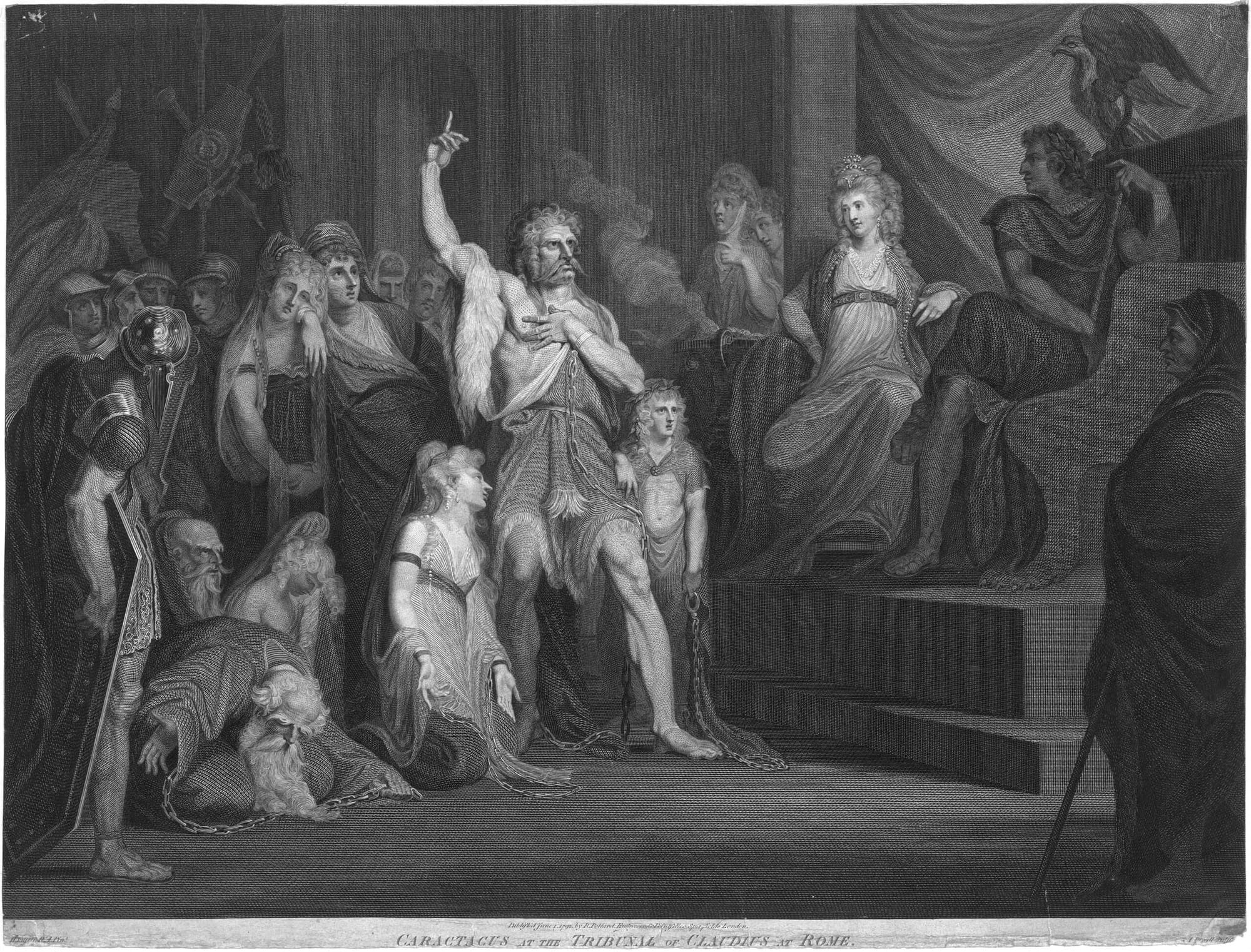

Though the Roman world had long tolerated eccentricity and excess, Caligula’s actions went far beyond. By 41 CE, the Praetorian Guard intervened—assassinating the emperor and casting uncertainty over the future of imperial power. In the wake of Caligula’s death, some factions even considered restoring the Republic.

Yet it was the army, not the Senate, that determined the next step. In a move that startled many, Claudius—long dismissed as unfit for rule—was proclaimed emperor. As the last surviving adult male in the Julio-Claudian line, he was a politically convenient choice. But what followed defied all expectations.

Claudius would be remembered not only for consolidating power after a time of crisis, but for expanding the empire’s borders.

Bartolomeo Passarotti’s painting, The Emperor Claudius. Public domain

Britain, which had remained out of reach since Julius Caesar’s expeditions, was now firmly brought under Roman control. New provinces were added in North Africa and the East, and colonies were planted in frontier regions to strengthen imperial presence. He restructured Rome’s administration with remarkable efficiency, delegating key branches of governance—such as the treasury—to freedmen.

His attention to infrastructure resulted in the construction of aqueducts, roads, and a crucial new harbor at Ostia. He also took aggressive steps to secure Rome’s grain supply, ensuring stability in a region still haunted by Caligula’s disruptions.

While Claudius attempted to work with the Senate, the power balance shifted. The imperial office grew stronger; the Senate, weaker. This created lasting tension. His critics—most notably Seneca, who authored The Apocolocyntosis—portrayed him as foolish, dependent, and physically grotesque.

Later writers like Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio repeated these judgments, accusing him of being a tool of palace intrigue, dominated by his wives and freedmen. Yet the accomplishments of his reign suggest a more capable ruler. Claudius governed with a mixture of caution, delegation, and reform. Though his path to power was unconventional and his image often scorned, the legacy he left behind was one of expansion, stabilization, and administrative maturity.

Marked by Nature: Claudius and the Burden of Perception

Claudius, born on 1 August 10 BCE in Lugdunum, Gaul—modern-day Lyon—was the first Roman emperor born outside Italy. While his lineage placed him firmly within the Julio-Claudian dynasty, his physical condition set him apart from the expectations of Roman nobility.

Modern interpretations suggest that he may have lived with a congenital impairment consistent with what is now recognized as cerebral palsy, which would explain the difficulties he had with movement and speech. Lucius Annaeus Seneca mocked his speech in The Pumpkinification of Claudius, describing how:

“[...] they did not understand his reply because his voice was disturbing and confusing to the ear [...]

His tongue was not intelligible—not Greek was he, nor Roman, nor of any noted race [...]”.

Roman society, steeped in ideals of physical perfection and eloquence, was often cruel in its judgment. According to Suetonius:

“[...] almost the whole course of his childhood and youth he suffered so severely from various obstinate disorders that the vigour of both his mind and his body was dulled, and even when he reached the proper age he was not thought capable of any public or private business.”

Although he reportedly possessed a dignified appearance while seated or lying down, the same author recounts the traits that provoked mockery:

“He possessed majesty and dignity of appearance, but only when he was standing still or sitting, and especially when he was lying down [...] he would foam at the mouth and trickle at the nose; he stammered besides and his head was very shaky at all times, but especially when he made the least exertion [...]”.

Cassius Dio offers further detail, writing:

“[...] physically he was in poor shape, and his head and his hands shook slightly. Because of this he also had a slight stammer, and so he himself did not read out all the measures that he introduced to the senate, but gave them to the quaestor to read [...]

As for those measures he did read out for himself, he would generally do this seated. Furthermore, he was the first of the Romans to use a covered chair.

This started a trend; for since that time right down to the present day not only emperors, but also ex-consuls have been carried on such chairs [...]”.

Even within his own household, Claudius was viewed with contempt. His mother reportedly called him:

“a monster of a man, not finished but merely begun by Dame Nature,”

while his grandmother showed him open disdain. His sister is said to have exclaimed that she hoped:

“the Roman people might be spared so cruel and undeserved a fortune”

when she heard he might one day become emperor.

Some modern analyses argue that the long-standing belief that Claudius suffered from polio was shaped by 20th-century preoccupations. However, others suggest that cerebral palsy, particularly a mild form involving spasticity, more accurately explains the symptoms described in ancient sources.

These accounts, often colored by political hostility, may have exaggerated his impairments. Yet, Claudius himself seems to have been aware of how he was perceived and how that perception could impact his speech—especially in public, unprepared moments or debates. Reports suggest he could speak clearly when reading from a script, as both Augustus and Tacitus observed.

From what can be inferred about his early development, his condition appears to have been present from birth—supporting the view that it was not a viral infection like polio, but likely cerebral palsy. Suetonius quotes his mother referring to him as:

"a man, not finished but merely begun by [...] Nature,"

This implied she recognized something was different shortly after his birth. This further distances his condition from polio, which is typically acquired after birth through exposure to contaminated water and is not hereditary.

Despite the limitations placed on him, Claudius received an exceptional education. His tutor was none other than the historian Livy. Claudius would later write prolifically: a twenty-book history of the Etruscans, an eight-book history of Carthage—both in Greek—and a forty-one book account of Roman history from 31 BCE onward, alongside his own autobiography.

None of these texts survive. One early work even defended the statesman Cicero, a bold and politically risky move for the time, hinting that Claudius may have harbored republican sympathies. When he ascended to power in 41 CE, the empire was in crisis, including a severe grain shortage. Claudius moved swiftly to stabilize the situation. Suetonius recounts that:

“[...] there was a scarcity of grain because of long-continued droughts, he was once stopped in the middle of the Forum by a mob and so pelted with abuse and at the same time with pieces of bread, that he was barely able to make his escape to the Palace by a back door; and after this experience he resorted to every possible means to bring grain to Rome, even in the winter season.

To the merchants he held out the certainty of profit by assuming the expense of any loss that they might suffer from storms, and offered to those who would build merchant ships large bounties, adapted to the condition of each.”

Contemporary visual representations, such as statues, do not reflect his physical impairments. This is not unusual for the period, as imperial portraits were often idealized.

Even centuries later, other heads of state—like Franklin Delano Roosevelt—took great care to conceal the visible signs of their disability from public view. In both cases, there remained a cultural discomfort with visible deviation from the ideal, despite their effectiveness as leaders. (Emperor Claudius I: the man, his physical impairment, and reactions to it, by Keith Armstrong)

Claudius and the Senate: Cooperation, Control, and the Illusion of Balance

When Claudius assumed power in 41 CE, he inherited not only an empire unsettled by Caligula’s tyranny but a Senate that viewed him with suspicion. His rise, orchestrated by the Praetorian Guard, came amid widespread unease, conspiratorial murmurs, and resentment among senators.

Despite this, Claudius sought to mend relations. He extended amnesty to his political opponents, including those who had favored restoring the Republic or eyed the throne themselves, and allowed many of them to attain consulships. To further calm tensions, Claudius reversed some of Caligula’s unpopular policies and showed overt signs of respect toward the Senate.

In a striking gesture, he would rise in the Senate House to address the consuls—a practice even Julius Caesar had failed to observe consistently, often citing health reasons for remaining seated. Claudius also made an effort not to flaunt his authority with excessive displays of triumphal attire and was attentive to the personal and ceremonial needs of individual senators.

His participation in the Senate’s festivals and proceedings was earnest—he was more active in senatorial sessions than any emperor since Augustus in his prime. He involved the Senate in discussions and decision-making where possible, hoping to sustain a cooperative relationship.

In public imagery, he projected himself not as a rebuilder of the Republic, but as a protector of libertas Augusta—the stable, structured liberty introduced by Augustus. Yet, the Senate’s authority waned under his rule.

Claudius may have spoken as though the Senate remained the empire’s highest body, once remarking that the emperor was in effect a “committee of one” entrusted with refining and presenting matters to the full Senate. But in practice, the Senate’s influence paled in comparison to the centralizing power of the emperor.

Claudius increasingly took it upon himself to bypass the Senate’s control over appointments, selecting men he deemed capable regardless of pedigree. Though his early clemency suggested a spirit of cooperation, a wave of conspiracies and assassination attempts early in his reign shifted his approach.

Punishments grew harsher, likely reflecting disappointment at the Senate’s refusal to embrace a more collaborative arrangement. As repression increased, so did hostility from the senatorial class. By the end of his reign, Claudius’s enemies claimed that he had overseen the executions of 35 senators and over 300 members of the equestrian order.

One of the most contentious aspects of his Senate policy was his effort to expand its membership beyond Italy. Claudius advocated for the inclusion of provincial elites from Gaul, even from regions still viewed as culturally backward by Roman standards. In a rare surviving speech delivered in 48 CE, Claudius argued that Rome’s strength had always rested on its ability to absorb new peoples and reshape its constitution to meet the needs of empire.

The Gauls he nominated were already Roman citizens and legally entitled to Senate representation, but they faced opposition purely on the basis of not being Italian. The senatorial class, proud and exclusive, resisted relinquishing its long-held monopoly on honors and office. When one of his Gallic candidates was rejected, Claudius resolved to institutionalize change.

He revived the long-neglected office of censor, assuming it jointly with Lucius Vitellius between 47–49 CE. This role allowed him to restructure the Senate and population registers, officially assessing citizens by birth, property, and moral standing. Through this, he could legitimize new admissions and enforce his vision of an expanded, imperial Senate.

Although the integration of provincial elites was controversial in Claudius’s lifetime—mocked as favoritism toward foreigners—it soon became a normalized policy. Just five decades later, a provincial Spaniard, Trajan, would ascend to the throne. But in Claudius’s own time, his proposals triggered xenophobic resistance and sharpened his divide with Rome’s traditional aristocracy.

The Wives, the Heirs, and the Poisoned End: Claudius’s Final Act

Before ascending the throne, Claudius had already married his third wife, Valeria Messalina, a politically advantageous union thanks to her lineage—she was the great-granddaughter of Octavia, sister of Augustus. Though significantly younger than Claudius, Messalina soon gave birth to a son, Britannicus, not long after Claudius became emperor. As the direct male heir, Britannicus represented dynastic stability, and his mother’s influence grew accordingly.

Messalina did not remain idle in securing her son’s place. She eliminated political rivals and women she viewed as threats to her status. Claudius himself may have been complicit in some of these removals, particularly if the individuals posed danger to his rule.

While Roman authors, especially Tacitus, vilified her for sexual excesses, describing her indulgence in “untried debaucheries,” it is now understood that she likely used sexuality as a political tool—to compromise men, manipulate outcomes, and strengthen her own position. The most dramatic episode came in 48 CE, when Messalina entered into a marriage with Senator Gaius Silius.

Ancient sources present this either as the final act of an affair or as a calculated political move—perhaps a conspiracy to depose Claudius or a reaction to Agrippina and her son Nero rising in favor. Others suggest that Claudius’s powerful freedmen, now seeing Messalina as a threat, engineered her fall. Once the emperor was informed of the marriage, Messalina was executed.

Despite vowing never to marry again, Claudius reconsidered within months—likely under the influence of his inner circle. From a list of candidates presented by his freedmen, he chose Agrippina the Younger, his own niece.

This required a change in Roman law, which was passed with senatorial approval, marking the marriage as a unifying political act. In 50 CE, Claudius formally adopted Agrippina’s son, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, who then became known as Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus Caesar. That same year, Agrippina received the title Augusta, a status no imperial consort had held since Livia.

Though succession plans were never formally declared, Nero had the advantage of age—three years older than Britannicus—and gained office eligibility earlier. In 51 CE, Nero donned the toga of manhood and was quickly accepted as Claudius’s intended heir.

He solidified his position in 53 CE by marrying Claudius’s daughter. The growing power of Agrippina and Nero stirred unease in certain circles, and this tension formed the backdrop to Claudius’s sudden death in 54 CE—believed by many ancient sources to have been murder.

According to Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio, Claudius was poisoned—possibly by mushrooms, administered either directly or with the help of his physician. Upon his death, Nero was immediately acclaimed as imperator by the Praetorian Guard and swiftly confirmed by the Senate.

Suetonius noted that even if Nero was not the one who orchestrated Claudius’s death, he acknowledged his role and later mocked the episode. He reportedly called mushrooms “the food of the gods” and jested that Claudius had stopped “playing the fool among mortals,” twisting the Latin morari for comic effect. His mockery extended to disregarding many of Claudius’s decrees, which he labeled the products of a madman:

“…even if he was not the instigator of the emperor's death, he was at least privy to it, as he openly admitted; for he used afterwards to laud mushrooms, the vehicle in which the poison was administered to Claudius, as ‘the food of the gods,’ as the Greek proverb has it.

At any rate, after Claudius's death he vented on him every kind of insult, in act and word, charging him now with folly and now with cruelty; for it was a favourite joke of his to say that Claudius had ceased ‘to play the fool among mortals,’ lengthening the first syllable of the word morari, and he disregarded many of his decrees and acts as the work of a madman and a dotard.

Finally, he neglected to enclose the place where his body was burned except with a low and mean wall."

Suetonius

Though Claudius was deified soon after his death, the act was hollow in some quarters. Upper-class Romans ignored or ridiculed it, and Seneca’s biting satire Apocolocyntosis divi Claudii openly scorned the dead emperor. Even Nero’s accession speech criticized Claudius’s decisions and failures.

Yet after Nero’s own fall and the rise of the Flavian dynasty, Claudius’s reputation saw a modest rehabilitation. The Flavians recognized the stability he had brought and honored his deification more sincerely.

Though his legacy would again fade, modern historians in the 19th and 20th centuries began reevaluating his reign, identifying it as a pivotal moment that helped shape Rome’s future. Even if his rule was not universally admired in his lifetime, the simple fact of Claudius's competence—especially when viewed beside the chaos of Caligula and the cruelty of Nero—has helped preserve a legacy defined less by spectacle and more by function. (Claudius: The Life and Legacy of the Emperor Who Stabilized the Ancient Roman Empire after Caligula, By Charles River Editors)

Claudius may never have commanded admiration through grandeur or charisma, but in many ways, his reign redefined what imperial success could look like. He did not inspire through oratory or battlefield heroics; instead, he stabilized an empire recovering from madness, introduced bureaucratic reforms that would shape governance for generations, and quietly expanded Rome’s frontiers.

History tried to reduce him to a joke — a stammering accident of dynastic fortune. Yet in hindsight, Claudius stands as a reminder that effective leadership often comes not from the expected mold, but from those willing to build, revise, and govern when others collapse. The empire may have mocked him — but it also endured because of him.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: