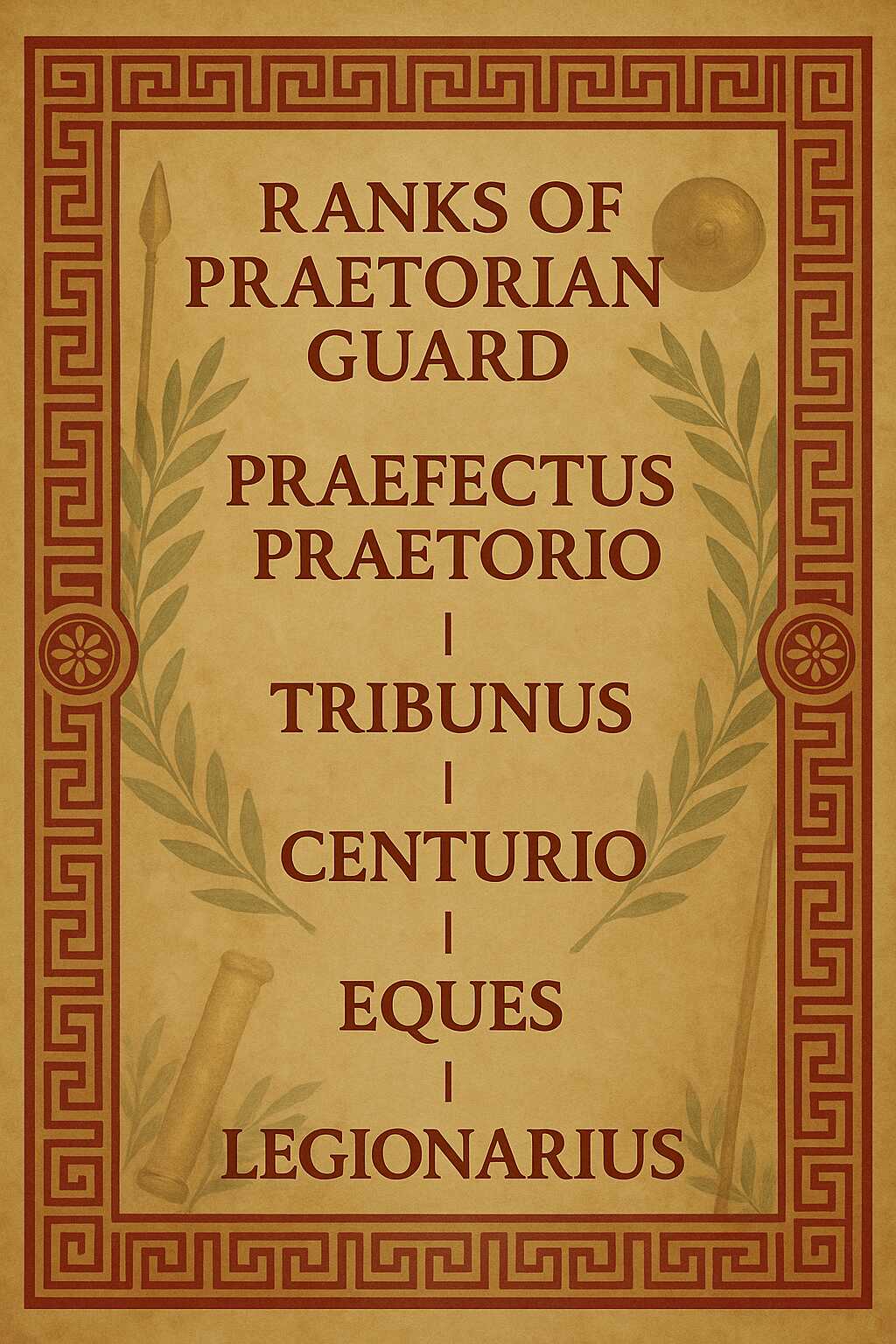

Who were the Praetorian Guard, Rome’s Elite Bodyguards?

Beyond their role as imperial bodyguards, the Praetorian Guard operated as an elite security force, enforcing state authority through surveillance, arrests, and executions.

From the shadows of Rome’s palaces to the bloodstained floors of imperial chambers, the Praetorian Guard stood as both protectors and executioners of emperors. Established by Augustus as an elite force sworn to defend the throne, they quickly evolved into something far more dangerous—the true power behind the purple.

For centuries, they dictated the fate of emperors, raising some to power and cutting others down in cold betrayal. From Sejanus’ ambition to Caligula’s assassination, from the infamous auction of the empire to their final downfall under Constantine, the Praetorian Guard’s story is one of loyalty, corruption, and ruthless ambition.

Protectors, Enforcers, and Political Players

The Praetorian Guard was primarily responsible for safeguarding the life of the emperor and, when necessary, his immediate family. While their role as protectors is often overshadowed by their political involvement, their effectiveness in security operations was significant. In the early empire, assassinations were typically carried out by individuals with pre-existing personal access to the emperor, allowing them to bypass security measures.

Random attacks by lone assassins, which are a primary concern for modern intelligence agencies, were rare in the Roman world.

A possible representation of how a lone assassin would look in the Roman Empire. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

Beyond imperial protection, the Guard’s responsibilities extended into state security and law enforcement. The Guard acted as an instrument of political control, conducting arrests and executions on behalf of the emperor.

In some cases, their mere presence was enough to pressure political enemies into committing suicide, allowing the emperor to avoid direct association with their deaths. A well-documented instance of this is the fate of Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, whose constant surveillance by the Guard contributed to his eventual demise (Tacitus, Annals).

Public Security and Firefighting

The Praetorian Guard also played a key role in maintaining order during public events, particularly those attended by the emperor. Their presence was both a protective measure and a demonstration of imperial authority, ensuring the safety of Rome’s citizens.

Beyond their responsibilities in political and public security, the Guard also had a firefighting role. Archaeological evidence and inscriptions indicate that Praetorians actively participated in extinguishing fires in the capital, a duty not commonly associated with elite military forces. One inscription from Ostia commemorates a Praetorian who died while combating a blaze (ILS 9494), highlighting their involvement in urban safety beyond military and political functions.

The Paradox of Power: Loyalty and Threat

The stationing of the Guard in Rome presented a paradox for emperors. As the closest military force to the imperial palace, the Praetorians served as the emperor’s first line of defense, yet they also posed a significant internal threat. The command of the Guard was a highly sensitive position, requiring careful management to prevent any one individual from gaining excessive power.

To mitigate the risk of a Praetorian coup, emperors structured the prefecture as a collegiate office, appointing two equally ranked prefects rather than a single commander. The association of the prefecture with the equestrian order also served as a safeguard, preventing high-ranking senatorial figures from controlling the empire’s most powerful military unit.

Despite these measures, some emperors took extraordinary precautions to ensure the loyalty of their protectors. Commodus, for instance, replaced his Praetorian Prefects frequently, at times appointing individuals to the position for mere hours. According to the Historia Augusta, one prefect’s tenure lasted only six hours before being dismissed, illustrating the emperor’s deep mistrust of the Guard’s leadership.

Casperius Aelianus and the Politics of Loyalty

Among the many figures who commanded the Praetorian Guard, Casperius Aelianus stands out for his unique political influence. Aelianus first served as Prefect under Domitian, later returning to the role under Nerva, likely as a concession to the Praetorians angered by Domitian’s assassination (Dio Cassius)

Tensions between Nerva and the Guard came to a head when Aelianus led the Praetorians in demanding the execution of high-ranking officials responsible for Domitian’s murder—despite the emperor’s reluctance. The situation was only resolved when Trajan intervened, removing Aelianus from power. However, Dio’s account is ambiguous, leaving room for debate as to whether Trajan executed Aelianus or simply allowed him to retire.

“He sent for Aelianus and the Praetorians who had mutinied against Nerva, pretending that he was going to employ them for some purpose, and then put them out of the way.

When he came to Rome, he did much to reform the administration of affairs and much to please the better element; to the public business he gave unusual attention, making many grants, for example, to the cities in Italy for the support of their children, and upon the good citizens he conferred many favours”.

Cassius Dio, Roman History

Some modern scholars suggest that Aelianus may have played an unspecified role in securing Trajan’s rise to power, possibly explaining why he was not immediately executed. Alternative theories propose that his loyalty was not to Trajan but rather to the Flavian dynasty, as some sources claim he had served under Vespasian in Judaea.

It is also possible that Aelianus’ career began under Domitius Corbulo, whose legions contributed key supporters to the Flavian bid for power. If this is the case, his actions may have been motivated more by a personal commitment to the Flavian cause than by any allegiance to Trajan.

Given Trajan’s own public loyalty to Domitian, Aelianus may have expected clemency rather than removal. Regardless of his ultimate fate, Trajan had no choice but to eliminate a prefect who had openly defied imperial authority (The Classical Review, Jonathan Eaton for "The Praetorian Guard. A History of Rome’s Elite Special Forces" by Snadra Bingham)

The Political Influence of the Guard in Roman History

The Praetorian Guard has frequently been described as a politically motivated force, often associated with self-interest and opportunism. In modern discourse, it is sometimes referenced as a symbol of an authoritarian security presence. Within the field of ancient history, contemporary sources typically portray the Guard as a pragmatic and calculating entity, engaged in numerous political maneuvers and betrayals.

From the ascension payments extracted from Caligula and Nero to their involvement in the assassination of Commodus and the auctioning of imperial power to Didius Julianus, the Guard has been the subject of significant historical scrutiny. Although many accounts document their actions, there has been little analysis of their broader consequences.

While existing studies examine specific incidents involving the Guard, few attempt to trace a larger narrative connecting these events to the political shifts in Rome, particularly in relation to the reforms of Diocletian and Constantine. Understanding the Guard’s development and influence requires an examination of key moments in their history, considering both their actions and their effects.

It is important to recognize that not all members of the Praetorian Guard participated in these events in the same manner. Some plots and assassinations were initiated by Prefects without broader Guard involvement, while others were carried out by the rank and file independent of their commanders.

Despite these distinctions, it is possible to observe a broader development in how the imperial position was perceived. The concept of what it meant to be emperor in the Early Principate differed significantly from its meaning in the later empire, particularly by the reigns of Philip the Arab or Macrinus. Various explanations have been proposed to account for this transformation, and one factor that warrants further examination is the political role and influence of the Praetorian Guard within these broader shifts in Roman governance.

The Origins and Influence of the Praetorian Guard in Imperial Rome

The Praetorian Guard is widely regarded as a defining feature of imperial Rome, a distinction justified by its absence during the Republican era. The earliest reference to a praetorian appears in 63 BCE, as noted by Sallust, and later, Julius Caesar used the term for a cavalry unit in his army.

However, these early mentions of praetorians differ from the force established by the Second Triumvirate. At the outset of their rule, the Triumvirs entered Rome with their own personal "praetorians," though these were not yet organized as a structured military unit. It was only after the Battle of Philippi that the first Praetorian cohorts were formally established, taking their name from the late Republic but not yet functioning in the way they would under the emperors.

These early guards were not yet a centralized force but served primarily as personal bodyguards for Augustus, similar to his Germanic bodyguards. Upon becoming princeps, Augustus formalized their role, creating a structured Praetorian Guard to secure his position as Rome’s sole ruler while avoiding the appearance of a military dictatorship.

He officially established the Guard in 27 BCE, forming nine cohorts of 500 men each, strategically stationed outside the city to avoid an overt military presence while ensuring that their influence could be deployed when necessary. Unlike regular legionaries, Praetorians dressed in civilian attire, carrying swords but no armor, reinforcing their role as enforcers of imperial power rather than a conventional army.

Though often portrayed as an elite force, early Praetorians were primarily recruited from the legions. Over time, their ranks expanded to include civilians and, under Septimius Severus, even non-Italians. Their privileges distinguished them from ordinary soldiers: initially earning 1.5 times the legionary wage, their pay later increased to three times that amount.

Additionally, their length of service was considerably shorter—set at 12 years in 13 BCE and extended to 16 years in 5 CE—a significant benefit for soldiers who rarely saw combat beyond Rome's walls. These advantages compensated for their lack of foreign campaigns and war plunder, ensuring their loyalty to the emperor. Unlike later emperors who relied on lavish payments, Augustus did not "purchase" the Guard’s allegiance outright but demonstrated his appreciation for their support through measured rewards.

Augustus’ final innovation was the creation of the Praetorian Prefect, a position —as aforementioned— designed to manage the Guard’s operations while acting as an intermediary between the emperor and the cohorts. Though some emperors appointed a single prefect, Augustus initially divided power between two equestrian officers, a decision aimed at preventing any individual from accumulating excessive influence.

The role was officially limited to organizing the Guard and ensuring the emperor’s protection, yet as later events would show, Prefects often extended their authority beyond these confines.

A drawing by Jean Lepautre, showcasing the last moments of Emperor Elagabalus, as he is assassinated by his Praetorian Guard. CC0 1.0

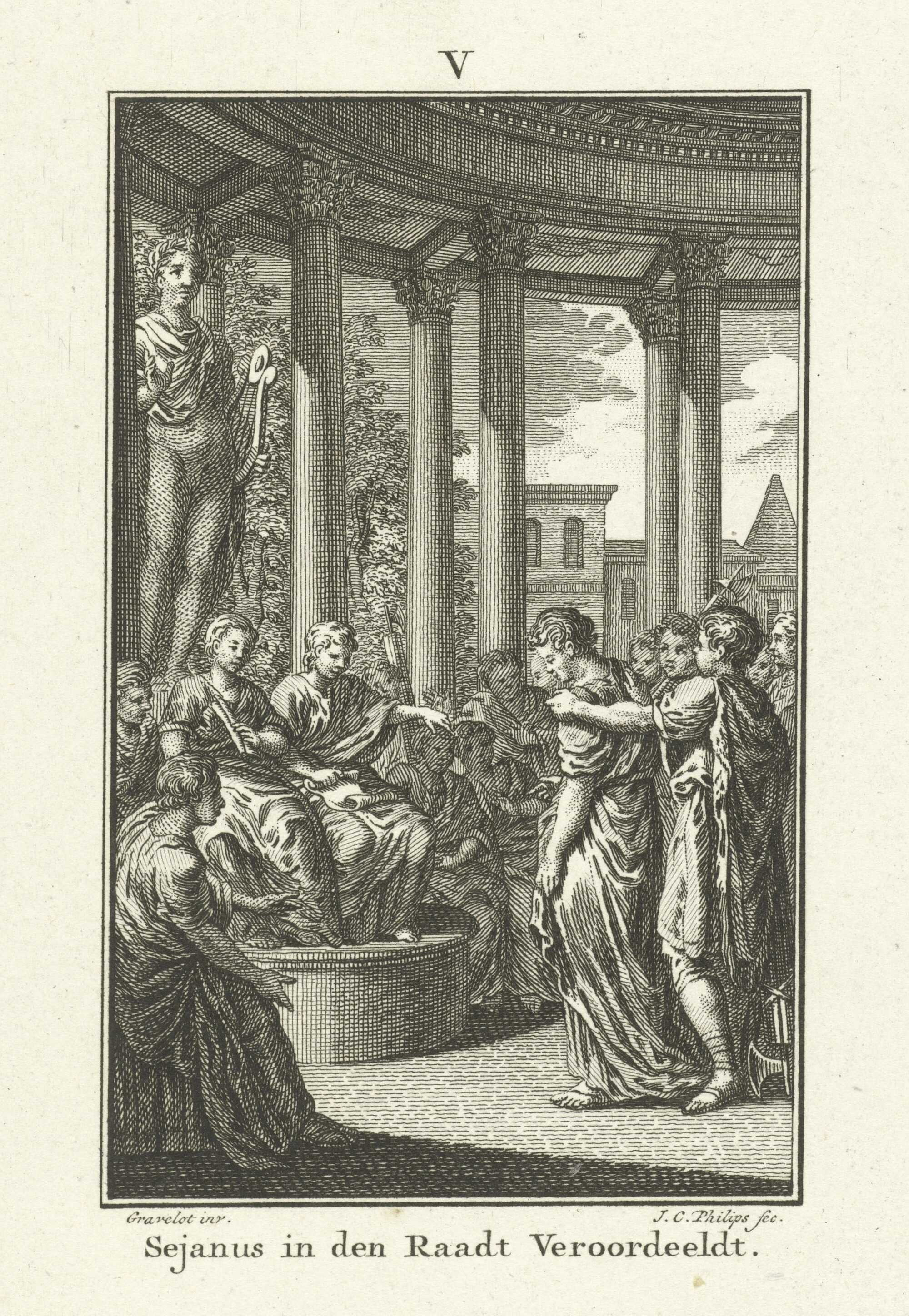

Under Tiberius, the dangers of consolidating power within a single Praetorian Prefect became apparent. Preferring to govern from Capri, Tiberius entrusted administration and military oversight to Sejanus, the sole prefect of the Guard.

Sejanus' reputation among ancient sources is complex — some depict him as the first prefect to challenge imperial authority, orchestrate assassinations within the imperial family, and consolidate power for himself. However, historical accounts also highlight his competence and dedication, qualities that earned him numerous honors, including an unprecedented double consulship despite his equestrian status.

His influence extended to the legions, as his image was carried alongside Tiberius’, a rare distinction. Given his extensive authority and recognition, the question arises: why would he attempt a coup against Tiberius?

Some sources, particularly Tacitus, who was critical of both the imperial system and the Praetorian Guard, portray Sejanus as ambitious and manipulative. His reorganization of the Guard—centralizing them within Rome’s Castra Praetoria—was perceived by citizens as a move toward military dictatorship.

Further suspicions arose following the death of Drusus, Tiberius’ heir, with many blaming Sejanus for the event. Convinced that his prefect had overstepped, Tiberius orchestrated Sejanus’ downfall, summoning him under false pretenses before the Senate, where he was condemned, arrested, and executed:

“For the man whom at dawn they had escorted to the senate-hall as a superior being, they were now dragging to prison as if no better than the worst... and him whom they were wont to adore and worship with sacrifices as a god, they were now leading to execution.”

Cassius Dio

Sejanus’ punishment extended beyond himself—his entire family was executed, serving as a warning that any Praetorian Prefect attempting to challenge imperial authority would meet the same fate. However, rather than dismantling the Praetorian Guard, Tiberius replaced Sejanus with Quintus Macro, reinforcing the Guard’s continued influence in imperial politics.

Following Tiberius’ death, his successor Caligula sought to secure the Praetorian Guard’s loyalty through donatives—a practice that would become a defining feature of imperial successions. Caligula’s relationship with the Guard, however, was strained, particularly with Prefect Cassius Chaerea, whom the emperor frequently insulted.

This hostility culminated in Caligula’s assassination, orchestrated by Chaerea and other conspirators who, as Dio Cassius notes, initially hesitated but ultimately acted for both personal and political reasons:

“both on their own account and for the common good.”

Despite their involvement in the plot, the Praetorian Guard did not immediately impose a successor. Instead, a faction of Praetorians discovered Claudius hiding in the palace, recognized him, and escorted him to the Castra Praetoria, where he was proclaimed emperor.

To consolidate his rule, Claudius issued a generous donative, reinforcing the link between military support and imperial authority. At the same time, he ordered the execution of Chaerea while allowing his fellow prefect Sabinus to commit suicide. By doing so, Claudius both punished the assassins and reaffirmed the Guard’s essential role in upholding imperial power.

Claudius’ rise marked a turning point: the illusion that emperors ruled independently of military backing had faded. His coinage prominently displayed the Castra Praetoria, bearing the inscription IMPER. RECEP., underscoring the Guard’s role in his ascension.

Though Claudius occasionally criticized the Guard’s complacency, he did not attempt to curtail their influence, instead maintaining their privileged status through continued payments. Their loyalty, however, appeared tied less to the emperor’s person and more to the financial rewards granted upon each succession.

Upon Claudius’ death, Nero ascended the throne, continuing the tradition of issuing a donative to the Guard. His reign was initially guided by his mother Agrippina and Prefect Sextus Burrus, though over time, Nero distanced himself from their influence. By 65 CE, a conspiracy arose involving Praetorian Prefect Sulpicius Asper and Senator Gaius Piso, motivated not by personal ambition but by concerns over Nero’s conduct:

“disgraceful behaviour, his licentiousness, and his cruelty.”

Cassius Dio

Although this plot failed, discontent among the Guard grew, culminating in 68 CE, when they abandoned Nero and declared support for Galba, marking a pivotal moment in their history. From this point forward, emperors could no longer claim absolute authority without the explicit backing of the Praetorian Guard. (What Impact did the Praetorian Guard have on the Political Climate of the Roman Empire?, by Adam Renner)

This episode, and subsequent events, illustrate how the Guard’s political influence shaped the imperial system. Rather than remaining mere protectors, they evolved into kingmakers, directly influencing succession, stability, and governance within the Roman Empire.

The Praetorian Prefect: More Than a Commander

The Praetorian Prefect was one of the most powerful figures in the empire, second only to the emperor. Unlike ordinary military commanders, the prefect’s responsibilities extended into governance, law enforcement, economic management, and intelligence operations. While the emperor was the "first citizen" (princeps), the prefect functioned as a prime minister, overseeing matters that went beyond military affairs.

Some of the key administrative areas under Praetorian control included:

- Food supply management – The Praefectus Annonae ensured the stable distribution of grain, particularly in Rome, preventing shortages and social unrest.

- Law enforcement and city security – The Praefectus Vigilum oversaw public order, including crime prevention and firefighting operations.

- Provincial governance – The Praefectus Aegypti governed Egypt, Rome’s most vital grain-producing province.

By centralizing these critical sectors under military oversight, the Guard ensured that imperial rule was not just enforced through arms but also through control over Rome’s essential resources and political stability.

Espionage and Counterintelligence Operations

The Praetorian Guard was instrumental in intelligence gathering, ensuring that threats to the emperor and the state were identified, monitored, and neutralized before they could manifest. Among their most specialized units were the speculatores, a group of spies and military scouts responsible for:

- Infiltrating enemy territories and collecting information on foreign powers.

- Monitoring political dissidents within Rome and the provinces.

- Providing reconnaissance in military campaigns, giving commanders strategic intelligence.

The Roman postal system, under military control, played a key role in intelligence operations. This system allowed the emperor to monopolize communication networks, ensuring that vital information from the provinces reached him directly, without interference.

Inspired by Persian intelligence networks, the militarized postal system enabled surveillance across the empire, making it difficult for political conspiracies or foreign threats to go unnoticed.

A possible representation of a Roman Praetorian Guard securing a letter that contains crucial information for the Empire, as part of their espionage. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

Beyond simple intelligence gathering, the Guard also acted as an early counter-terrorism force. Roman authorities operated under the principle "Hospis, hostis est" (The guest is an enemy), which led to constant surveillance of foreigners in Rome. The Guard monitored diplomats, traders, and envoys to ensure that external threats were swiftly detected and addressed.

The Dacian Wars: The Guard’s Intelligence Capabilities in Action

A striking example of the Praetorian Guard’s intelligence role was its involvement in the Dacian Wars. Rome’s first campaign against Dacia was inconclusive, but it provided a crucial opportunity for the Guard to gather intelligence that would lead to Rome’s victory in the second war.

During the armistice between Rome and Dacia, the Guard:

- Infiltrated Dacian society, gathering intelligence on fortifications, water sources, and supply lines.

- Monitored Decebalus’ alliances, identifying potential threats and neutralizing diplomatic efforts to unite anti-Roman forces.

- Used elite cavalry units (equites singulares) to intercept Dacian messengers, preventing communications with Rome’s enemies.

This intelligence ensured that, by the time of the second Dacian War, Rome had detailed information on Dacia’s vulnerabilities, allowing for a far more decisive campaign. The Guard’s espionage efforts directly contributed to Rome’s ability to conquer and assimilate Dacia into the empire.

Control Over Economic and Political Structures

The Praetorian Guard’s authority extended into economic policy and governance, playing a role in enforcing imperial decrees and maintaining stability. Their influence was particularly evident in:

- Supervising taxation and financial policies, ensuring imperial revenues remained stable.

- Overseeing trade and commerce, particularly in Rome and key provinces.

- Maintaining road security and supply chains, which was vital for the movement of troops, goods, and intelligence.

Through these roles, the Guard acted as a stabilizing force within the empire, ensuring that imperial control was upheld not just through military might but also through economic regulation and administrative oversight.

Their involvement in governance also extended into Roman law. Many Praetorian Prefects were legal scholars, and their interpretations of imperial law influenced judicial decisions. Their presence ensured that the legal system operated in alignment with imperial authority, reinforcing the emperor’s role as the ultimate arbiter of justice.

From Guardians to Kingmakers

Although the Guard was initially intended to protect the emperor, their role evolved into something far more politically influential. Over time, the Praetorians became deeply involved in imperial successions, deciding who would rule Rome. By the 3rd century CE, their authority had expanded so significantly that the term “praetorianism” came to symbolize military rule over civilian governance.

The Guard’s ability to install and remove emperors demonstrated that their loyalty was not necessarily to the ruler but to the stability of Rome as they defined it. Their actions ensured that only those with sufficient military and financial backing could ascend to the throne, making them one of the most powerful institutions in Roman politics. (The Praetorian guard, Rome's intelligence service, by Mădălina Strechie)

The Praetorian Guard was one of the most complex and influential institutions of the Roman Empire, balancing roles in military security, intelligence, law enforcement, economic oversight, and governance. Their influence was felt not just in the halls of the imperial palace but across the entire structure of the empire, shaping its politics, economy, and military strategies.

From their espionage efforts in foreign campaigns to their role in economic and political administration, the Guard’s actions played a significant part in maintaining the stability of the empire. While their later years were marked by political interference and imperial assassinations, their core function remained the same—to ensure the continuity and security of Rome’s imperial rule.

Though the Guard was eventually disbanded by Constantine, the systems they pioneered in intelligence, counterintelligence, and administrative control would influence future military and security organizations for centuries to come. Their legacy remains one of control, enforcement, and the unrelenting pursuit of imperial stability.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: