What It Took to Survive as a Roman Citizen

Life in ancient Rome depended on knowing how the city worked in practice. Class, family, clothing, housing, food, and patronage shaped survival in a society where hierarchy governed every aspect of daily life.

Life in ancient Rome required more than legal status or civic pride. Survival depended on knowing how the city worked in practice: where you stood socially, how households functioned, what public space demanded, and how daily needs such as food, shelter, and clothing were managed within a rigid hierarchy. Rome did not offer comfort or protection by default. It rewarded those who understood its rules, read its signals correctly, and adapted to an environment where status, proximity, and custom shaped everyday life as much as law.

The Eternal City by 95 CE

By 95 CE, Rome was the largest city in the Mediterranean world, with a population that likely exceeded one million inhabitants. It was a densely built, crowded, and socially stratified metropolis, where monumental architecture stood alongside precarious living conditions. Marble temples, basilicas, and imperial fora dominated the city’s public image, while the majority of its population lived in multi-storey apartment buildings (insulae) constructed quickly and often unsafely.

The city’s infrastructure reflected both Roman engineering skill and its limitations. Aqueducts supplied vast quantities of water, feeding fountains, baths, and elite households, yet access was uneven and contamination common. Sewage systems existed in parts of the city, but waste disposal remained inconsistent, contributing to persistent health risks. Fire posed a constant threat, especially in districts packed with wooden structures, narrow streets, and open flames used for cooking and lighting

Social life in Rome was shaped by proximity rather than equality. Senators, equestrians, freedmen, slaves, migrants, and the urban poor shared the same urban space but experienced it very differently. Legal status determined access to protection, justice, and opportunity. Slaves and freedpeople formed a substantial portion of the population, performing essential labour while remaining vulnerable to abuse and sudden punishment. Citizenship conferred privileges, but it did not guarantee security.

Political power was concentrated at the top, yet its presence was felt daily. Imperial authority was visible in statues, inscriptions, and public ceremonies, while laws and regulations affected movement, trade, and behaviour. At the same time, informal systems—patronage, personal connections, neighbourhood networks—often mattered more than official structures for navigating everyday problems.

Food supply was a central concern. Rome depended heavily on imported grain, distributed through state systems to prevent unrest. Shortages, delays, or corruption could quickly lead to anxiety and disorder. Markets, taverns, and street vendors were essential to daily survival, particularly for those without stable income or household resources.

Entertainment and public spectacle played a significant role in urban life. Games, executions, theatrical performances, and public punishments were common features of the civic calendar, reinforcing social hierarchies while offering moments of distraction and collective experience. These events coexisted with constant reminders of mortality, from disease outbreaks to frequent funerals and roadside tombs.

Rome in 95 CE was therefore a city of contrasts: extraordinary wealth and persistent danger, sophisticated administration and everyday improvisation, monumental stability and fragile lives. To live there required awareness of risks, adaptability to rapid change, and an understanding of how to function within a city that rewarded resilience more reliably than comfort.

Where You Stood Mattered More Than Who You Were

Social class in ancient Rome was not defined by a single label, but by the cumulative answers to a series of legal and social distinctions. Whether a person was freeborn or freed, citizen or non-citizen, Italian or provincial, senator, equestrian, or without rank determined nearly every aspect of life.

These classifications governed taxation, marriage eligibility, political participation, legal protection, and even permitted clothing. Roman society functioned through visible hierarchy, and knowing one’s place was not merely a matter of etiquette but of survival.

At the apex of this system stood the emperor, followed by men of senatorial and equestrian rank. Beneath them were ordinary citizens without formal status, freedmen, and finally slaves. Women, regardless of wealth or family background, occupied a legally subordinate position, lacking independent civic authority. This hierarchy was reinforced in public space.

Seating arrangements in theatres and amphitheatres physically displayed social rank, with senators closest to the arena and women and slaves relegated to the highest tiers. Dress also served as a marker: the broad purple stripe identified senators, the narrow stripe equestrians, while most citizens rarely wore the toga at all.

Climbing Rome’s Ladder Without Falling Off

Senatorial rank was required for advancement along the cursus honorum and access to Rome’s highest offices. Unlike earlier periods, the imperial Senate was not restricted to old aristocratic families. Civil wars had thinned the traditional elite, and emperors increasingly admitted new men, including provincials. Entry, however, depended on wealth. A senator was required to possess at least one million sesterces in land and assets and was forbidden from engaging in trade.

The rewards included prestige, political influence, and proximity to imperial power, but that same proximity carried danger. Senators lived under constant scrutiny, and closeness to the emperor could quickly turn fatal.

Below them stood the equestrian order, defined by a lower property qualification of 300,000 sesterces. Equestrians increasingly filled administrative and managerial roles avoided by senators, especially under emperors who valued competence over lineage. Unlike the senatorial class, equestrian rank was open to freedmen, making it a key route of social advancement. Yet equestrians shared the same fundamental risk as senators: visibility to imperial authority without its protection.

Free, but Never Quite Equal

Freedmen formed a large and diverse social group. Roman society was unusual in the scale of manumission, and for many, slavery was a temporary condition. Freedmen could become citizens, conduct business, accumulate wealth, and even rise to equestrian status. However, they remained excluded from certain offices, military service, and marriage into elite families. Former imperial slaves often held significant administrative power, which provoked resentment from the traditional elite. Literary hostility toward imperial freedmen reflects social anxiety rather than their actual influence.

Women and slaves occupied a legally dependent position. Both were formally under the authority of another and lacked autonomous legal standing. Slaves had no personal rights but could hope for eventual manumission. Women, by contrast, had no comparable route to legal independence, despite occasional flexibility in practice. The law placed them below freedmen in formal status, regardless of family or wealth.

Living Outside Respectability

Below even slaves stood the infames, a category defined not by birth but by occupation and behaviour. Actors, dancers, gladiators, and prostitutes were legally marginalised, stripped of full civic rights despite their public visibility and popularity. Infamia functioned as institutionalised social shaming. Yet these figures occupied a paradoxical position: socially excluded but culturally central, attracting fascination from all levels of society, including the imperial household itself.

What Kept the System Together

Roman citizenship marked the sharpest legal divide of all. Citizens were protected from corporal punishment, torture, and crucifixion and retained the right to appeal directly to the emperor. Non-citizens lacked these safeguards entirely. Despite extreme inequalities, large-scale class conflict was relatively rare. Instead, Roman society was stabilised by amicitia, a system of reciprocal obligation linking patrons and clients across social boundaries.

Through patronage, individuals of lower status aligned themselves with powerful figures in exchange for protection, influence, or material benefit. Freedmen remained lifelong clients of their former masters, while elite patrons amassed large followings as visible demonstrations of power. This network of mutual dependence, rather than equality, limited unrest and bound Roman society together.

In Rome, class was not an abstract concept. It was a daily reality, enacted in law, space, clothing, and ritual. To understand Roman life is first to understand how carefully—and how relentlessly—difference was organised.

The Household Where Rome Was Made

Family sat at the centre of Roman identity, binding the living to both their ancestors and their descendants. Lineage mattered not only privately but publicly: elite households displayed ancestral death masks in their atriums, festivals such as Parentalia honoured the dead, and political reputation could be enhanced—or damaged—by claims about one’s family background. Roman writers treated ancestry as a serious measure of worth, and attacks on an opponent’s lineage were a recognised political tactic.

Under the emperors, family stability was elevated into state policy, reinforced through legislation that promoted marriage and child-rearing as moral duties essential to Rome’s survival.

The Roman household was structured around the authority of the pater familias, the male head who exercised legal control over property, finances, marriages, and dependants. His power extended over adult children and, in theory, even included the right to punish or kill members of his household. Yet this authority was often more fragile in practice.

Elite sons frequently remained financially dependent well into adulthood, while pursuing leisure, social ambition, and political connections beyond paternal control. Roman sources repeatedly reveal the tension between legal power and social reality, where fathers struggled to manage heirs whose behaviour reflected both privilege and excess.

Imperial ideology strongly promoted the household as a model of moral order, none more visibly than under Augustus. He legislated aggressively on marriage, adultery, and reproduction, rewarding large families and penalising those who failed to conform. Augustus also staged his own family as an example of traditional discipline, arranging marriages and careers for his children and relatives. Yet these efforts ended in public scandal, exile, and estrangement, exposing the limits of moral legislation when confronted with personal autonomy and elite resistance.

Women occupied a legally subordinate position within this structure. Expected to embody chastity, modesty, and domestic virtue, their primary social role was reproduction. Women held no political office, lacked voting rights, and were subject to male guardianship in financial matters. Augustus’ morality laws formalised these expectations, punishing adultery with exile and severe legal penalties.

At the same time, Roman literature reveals persistent anxiety about educated, outspoken women who operated beyond domestic boundaries, suggesting a reality more complex than official ideology allowed.

Slavery was embedded in every level of Roman family life. Slaves had no legal personhood, could not marry, and were subject to corporal punishment and sale at their owner’s discretion. Their treatment reflected directly on the reputation of the household: excessive cruelty invited public disapproval, while excessive leniency risked accusations of weakness. Although no serious challenge to slavery existed, imperial legislation gradually imposed limits on the most extreme abuses, particularly in the first century CE.

Children were viewed simultaneously as assets, responsibilities, and risks. Roman law granted the pater familias the right to decide whether a newborn would be raised or exposed, with physical fitness, gender, and economic capacity shaping that decision. Exposure did not always mean death, but it often resulted in enslavement.

Education, where available, focused on rhetoric and public performance, preparing elite boys for political life, while philosophical study was treated with suspicion by imperial authorities.

Despite the rigid hierarchy governing family life, Roman society avoided constant internal conflict through systems of obligation and reciprocity. Patronage relationships tied households together across social boundaries, creating networks of dependence that stabilised inequality. Family, in Rome, was therefore not only a private institution but a mechanism through which social order, authority, and continuity were maintained across generations.

What Your Clothes Said Before You Spoke

Clothing in Rome was never simply a matter of comfort. What a person wore immediately signalled gender, status, wealth, respectability, and even moral standing. Although Roman dress appears simple at first glance, its variations were socially meaningful and carefully observed.

For men, the tunic formed the foundation of everyday clothing. Its cut was basic, but its presentation allowed for distinction. Length, material, colour, and accessories such as belts all conveyed information about status and intention. Wool was common and affordable, while linen offered comfort in heat. Silk, though luxurious, attracted criticism for being unmanly and excessive.

Knee-length tunics were practical and fashionable, revealing legs that were expected to be hairless, reflecting broader Roman preferences for bodily grooming. Cloaks provided protection from the weather and could be lined with fur for warmth. Footwear was typically limited to sandals, sometimes reinforced with nailed soles for traction.

The toga, often imagined as universal Roman attire, was in fact reserved for formal occasions. Its complexity and impracticality made it unsuitable for daily wear. It functioned primarily as a public and political garment, worn by men seeking office or participating in civic rituals. Managing a toga required skill, and candidates often relied on slaves to prevent embarrassment. Its symbolic value far outweighed its usefulness.

Men’s appearance extended beyond clothing. Grooming mattered. Hair on the head was prized, while body hair was removed through plucking or burning. Baldness carried social stigma, prompting some elite men to resort to hairpieces. Attention to personal presentation reflected discipline, self-control, and conformity to elite norms.

Women’s clothing followed a more layered structure. The tunic formed the base, over which the stola marked respectability and marital status. A shawl, or palla, completed the outfit, serving both as outerwear and veil. Colour combinations allowed for display or discretion, depending on circumstance. Unlike men, women were not required to wear the toga.

Female grooming and adornment were highly visible markers of wealth and fashion. Jewellery, elaborate hairstyles, and skilled hairdressers signalled status. In the Flavian period, towering coiffures required hours of labour and specialist expertise. Simpler styles remained acceptable but carried different social connotations.

Children dressed much like adults, scaled down in size. Clothing, however, also carried protective meaning. Boys wore a bulla and girls a lunula, amulets believed to guard them from harm. These were surrendered at adulthood, marking the transition into full social participation. Boys then assumed the toga virilis, publicly signalling their new legal and civic status.

Across all ages and genders, clothing functioned as a visual language. It communicated belonging, ambition, respectability, and rank at a glance. To dress incorrectly was not merely a fashion error but a social risk, capable of attracting ridicule or suspicion in a society acutely attuned to appearance.

Where You Slept Said Everything

In Rome, accommodation was never a neutral matter. Where you stayed shaped daily routines, social exposure, and even personal safety. For the vast majority of the population—including newcomers to the city—life unfolded inside insulae, multi-storey apartment blocks packed tightly into Rome’s streets. These buildings were usually rented rather than owned, and could rise anywhere from three to eight storeys.

Notices advertising vacancies were commonly painted directly onto walls, offering anything from shops and storerooms to “high-class rooms,” all managed through an owner’s slave or agent.

Comfort was limited. Apartments lacked running water, private toilets, and cooking facilities. Residents relied on public latrines, bakeries, and takeaway food shops, turning basic bodily needs into social encounters where gossip circulated freely. Noise was unavoidable, especially in rooms above bathhouses, cookshops, or taverns, where activity continued well into the night. The most desirable apartments were on the first floor, safely above street level but close enough for a quick escape.

Danger was an accepted part of urban living. Fires were frequent, building standards inconsistent, and collapses common enough to inspire dark humour from Roman writers. Even well-connected investors lost properties to structural failure. Although Rome maintained a fire brigade, survival often depended on proximity to stairs and the ability to flee without hesitation. To live in an insula was to accept crowding, risk, and constant proximity to others.

Elite housing operated on entirely different principles. The townhouses of the wealthy were designed as both private residences and public arenas. Facing inward to shield occupants from the street, they opened into impressive atria where clients gathered each morning, ancestors were displayed in busts and masks, and status was carefully staged. Decoration was bold and intentional: vivid wall paintings, mosaics, statues—often Greek originals—signalled education, wealth, and cultural authority.

These homes were complemented by villas outside the city, particularly along the Bay of Naples. Here, space replaced congestion, and architecture expanded to include gardens, libraries, baths, and sea views. Such residences offered relief from Rome’s density while reinforcing elite identity through leisure and display.

Across the social spectrum, housing in Rome made hierarchy visible. Whether in a precarious upper-storey room or a carefully curated atrium, where you slept revealed not just how you lived, but where you stood.

Where Rome Bought Its Daily Life

Shopping in Rome was as much about timing, location, and spectacle as it was about goods. Fresh food was best found at the nundinae, the nine-day markets where farmers arrived before dawn, having travelled overnight to bypass restrictions on daytime wagons. Early arrival mattered, both to secure quality produce and to avoid the crush of later shoppers. For those unwilling to brave the crowds, permanent shops and markets offered alternatives, especially around the city’s forums.

The Forum Romanum sat at the heart of this commercial world. It was not a market alone, but a dense concentration of political, religious, judicial, and social life. Shoppers moved among temples, law courts, and monuments, often pausing to witness speeches, trials, or executions. The rostra in particular functioned as a focal point for public drama, repeatedly becoming the stage for unrest, violence, and spectacle.

Once the cultural circuit was complete, shoppers headed along the Via Sacra, Rome’s most prestigious retail street, where luxury goods such as jewellery, perfumes, and spices were sold at elite prices.

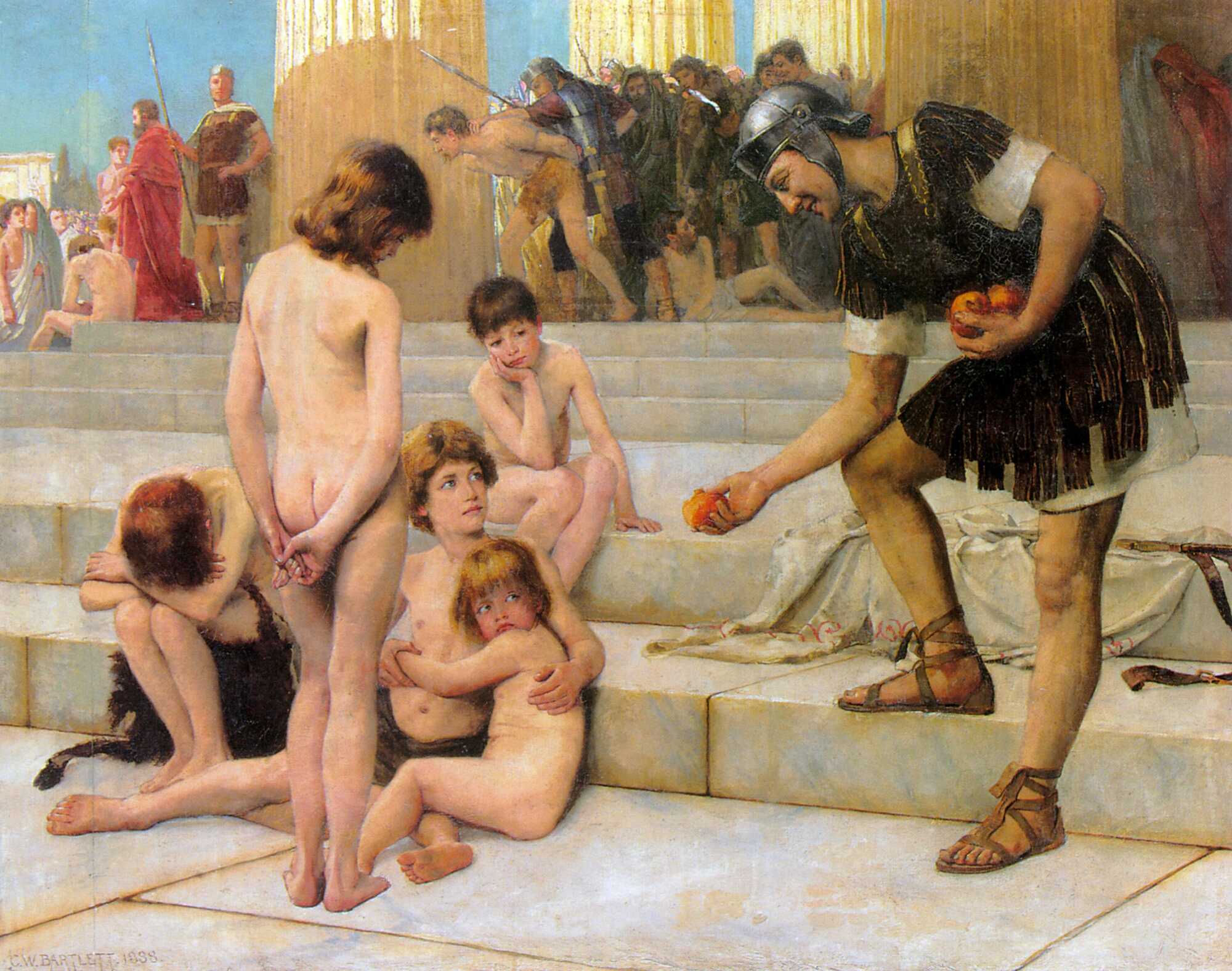

To relieve congestion, emperors created their own Imperial Forums, each lined with shops and dedicated monuments. These new spaces combined commerce with imperial self-display. Certain districts developed specialisms: bookshops clustered near the Forum of Domitian, vegetable markets occupied the Forum Holitorium, cattle were sold at the Forum Boarium, and slaves were traded at the Saepta Julia.

Buying slaves was itself a complex commercial process. Purchases were shaped by assumptions about ethnicity, climate, appearance, and skill. Greek slaves were favoured for education and medicine, others for physical labour or novelty value. Buyers weighed the merits of home-born slaves against newly captured ones, inspected health closely, and looked for useful traits such as literacy or training. Despite legal protections, the trade was understood to be deceptive by nature, and caution was expected.

Shopping in Rome therefore extended far beyond simple exchange. Markets doubled as social theatres, forums blended consumption with power, and even routine purchases reinforced hierarchy, taste, and status. To buy in Rome was to participate fully in the city’s public life.

Eating Well, Eating Poorly, Eating Everywhere

Roman food culture was shaped as much by empire and inequality as by taste. The range of foods available in the city was broad, drawing on agricultural produce from Italy and imports from across the Mediterranean world. Vegetables and pulses such as lentils, peas, beans, chickpeas, leeks, and cabbage formed staples, alongside fruits including grapes, figs, apples, pears, peaches, pomegranates, and olives.

Many of these could be preserved through pickling or drying, allowing consumption beyond their growing season. Mushrooms and chestnuts also featured among commonly available foods.

Central to Roman cooking was sauce, above all garum. This fermented fish sauce functioned as a universal seasoning and marker of culinary sophistication. Contemporary descriptions make clear both its popularity and its pungent origins, produced by salting fish entrails and leaving them to ferment in the sun. Despite (or because of) this process, garum was applied liberally across social classes and meals, becoming one of the most distinctive elements of Roman taste.

Access to food, however, varied sharply by status. Luxury ingredients and elaborate dishes were the preserve of the wealthy, while the urban poor relied heavily on the state grain dole. This grain was typically taken to local bakeries, as most Roman dwellings lacked cooking facilities. Bread formed the core of the poorer diet, supplemented when possible by vegetables, cheese, or small amounts of sausage.

The absence of private kitchens made cookshops and taverns an essential feature of daily life. These establishments served prepared food to be eaten on site or taken away and were frequented by all levels of society. Even emperors acknowledged their appeal, treating casual dining as a practical necessity rather than a social failing. Wall inscriptions and graffiti show that Romans also evaluated their dining experiences publicly, leaving comments that mixed complaint, humour, and blunt honesty.

Excess on Display: Dining Among the Wealthy

For Rome’s richest households, food was not simply nourishment but a form of social display. Wealthy Romans ate whatever they pleased and often chose their meals precisely for their cost, rarity, or shock value. Extravagance itself signalled status. Ancient writers record elite diners consuming substances not normally considered food at all, including perfumes, believed to sweeten the body from within.

Displays of excess extended to theatrical gestures such as dissolving pearls in vinegar and drinking the mixture, an act traditionally associated with Cleopatra and frequently cited as a symbol of conspicuous consumption.

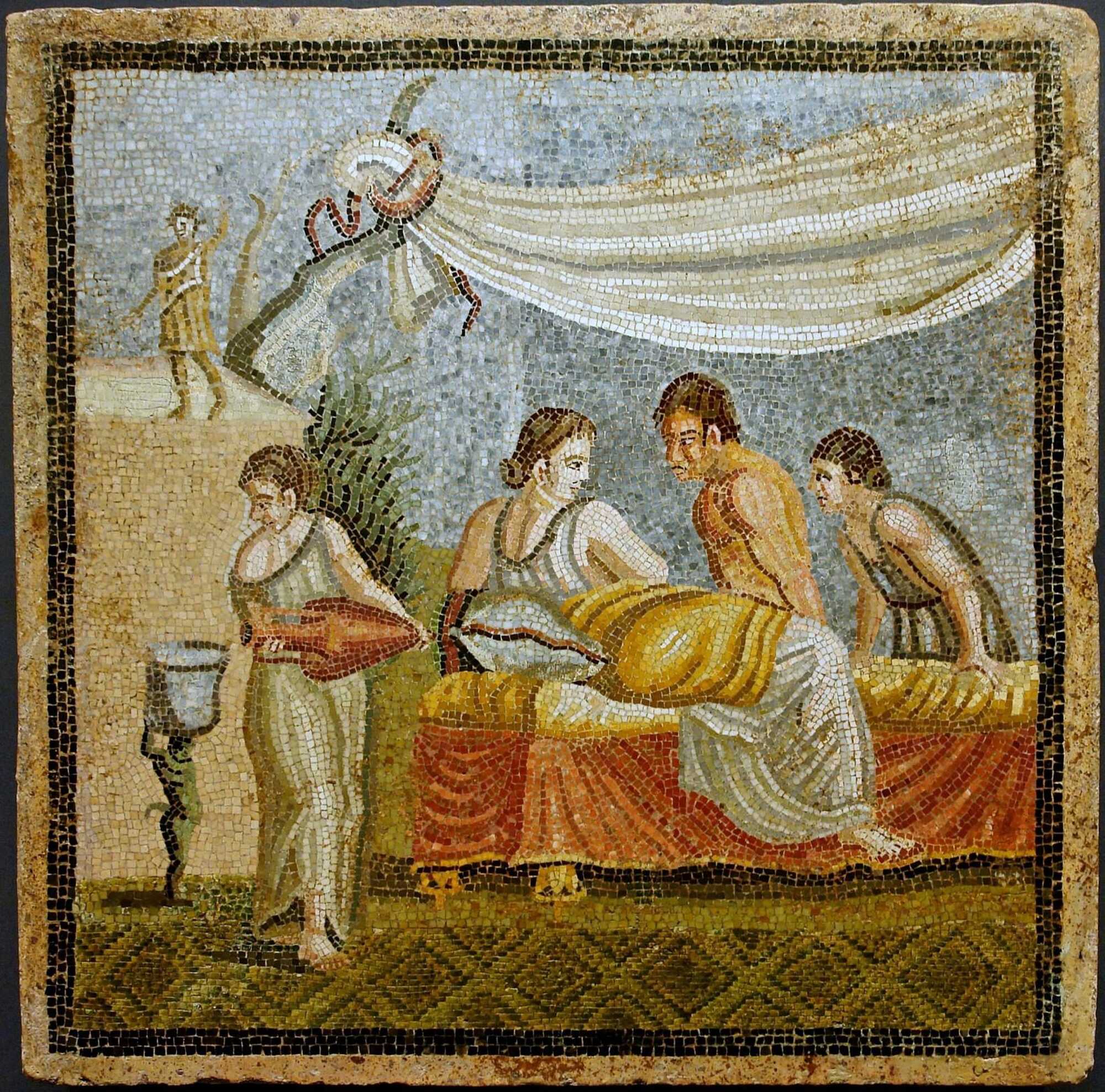

The primary setting for elite dining was the private dinner party. Securing an invitation required sustained social effort rather than reciprocal courtesy. Invitations were earned through persistence, strategic visibility, and careful cultivation of favour. Attendance itself functioned as a marker of inclusion within elite networks, while exclusion carried social meaning.

Dinner parties varied widely depending on the host. Imperial banquets, in particular, were unpredictable. Ancient sources associate them with sudden violence, intimidation, or calculated theatricality. Poisonings, executions, and armed interventions by guards are all recorded as interruptions to otherwise formal meals. Under Domitian, one dinner became infamous for its entirely black setting, from walls and couches to food and serving slaves, with tomb-like slabs placed beside guests. Such occasions were designed to unsettle as much as to impress.

More typical elite dinners followed established conventions. Guests reclined on their left sides on shared couches arranged around a central table, eating with the right hand. Seating arrangements carried clear social signals. The companions assigned to one’s couch reflected the host’s estimation of a guest’s importance, and diners were acutely aware of these hierarchies.

Conversation formed part of the performance, with wit offering the possibility of advancement and social missteps risking exclusion from future invitations.

Food at these gatherings could reach extreme levels of complexity and excess. Wealthy hosts drew inspiration from culinary collections such as those attributed to Apicius, serving dishes composed of rare animal parts and imported delicacies. Elaborate centrepieces included the so-called Trojan Hog, a roasted pig that released sausages when carved, and enormous fish chosen for their cost and the logistical effort required to prepare them. Presentation often mattered as much as flavour, with dishes floated in water channels or served by naked attendants, adding spectacle and risk to the meal.

Entertainment accompanied dining and was not always welcome. Guests might be subjected to poetry readings, musical performances, storytelling, or dance. Hosts occasionally inflicted their own literary ambitions on captive audiences, a prospect so dreaded that advance enquiries about planned entertainment were advisable. A poorly chosen performer could turn an evening into an endurance test rather than a pleasure.

One of the clearest signs of a bad dinner party was stinginess. Guests were sensitive to unequal treatment, particularly when inferior food or drink was served to them while the host enjoyed better fare. Such practices communicated relative standing within the host’s social circle with uncomfortable clarity.

Wine dominated Roman drinking culture. The most prized varieties came from Campania, especially Falernian wine from the slopes of Mount Falernus. Wine was never consumed unmixed; water, honey, or spices were added to avoid the stigma of barbarism. Beer was available but carried no prestige. Excessive wine consumption, however, was not merely tolerated but expected in elite settings, reinforcing the association between sociability, status, and indulgence.

Together, elite dining practices reveal a world in which food, drink, and hospitality operated as instruments of hierarchy, competition, and display. Meals were stages on which wealth, favour, and power were enacted as much as consumed. (“How to survive in ancient Rome” by L.J. Trafford)

To live in Rome was to move constantly between visibility and vulnerability. Status shaped where one sat, what one wore, where one slept, and how one ate, but it never eliminated risk or dependence. Family authority, patronage, and custom offered structure rather than security. Survival rested not on ideals, but on fluency: understanding hierarchy, reading social cues, and adapting daily to a city that rewarded awareness more reliably than virtue.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: