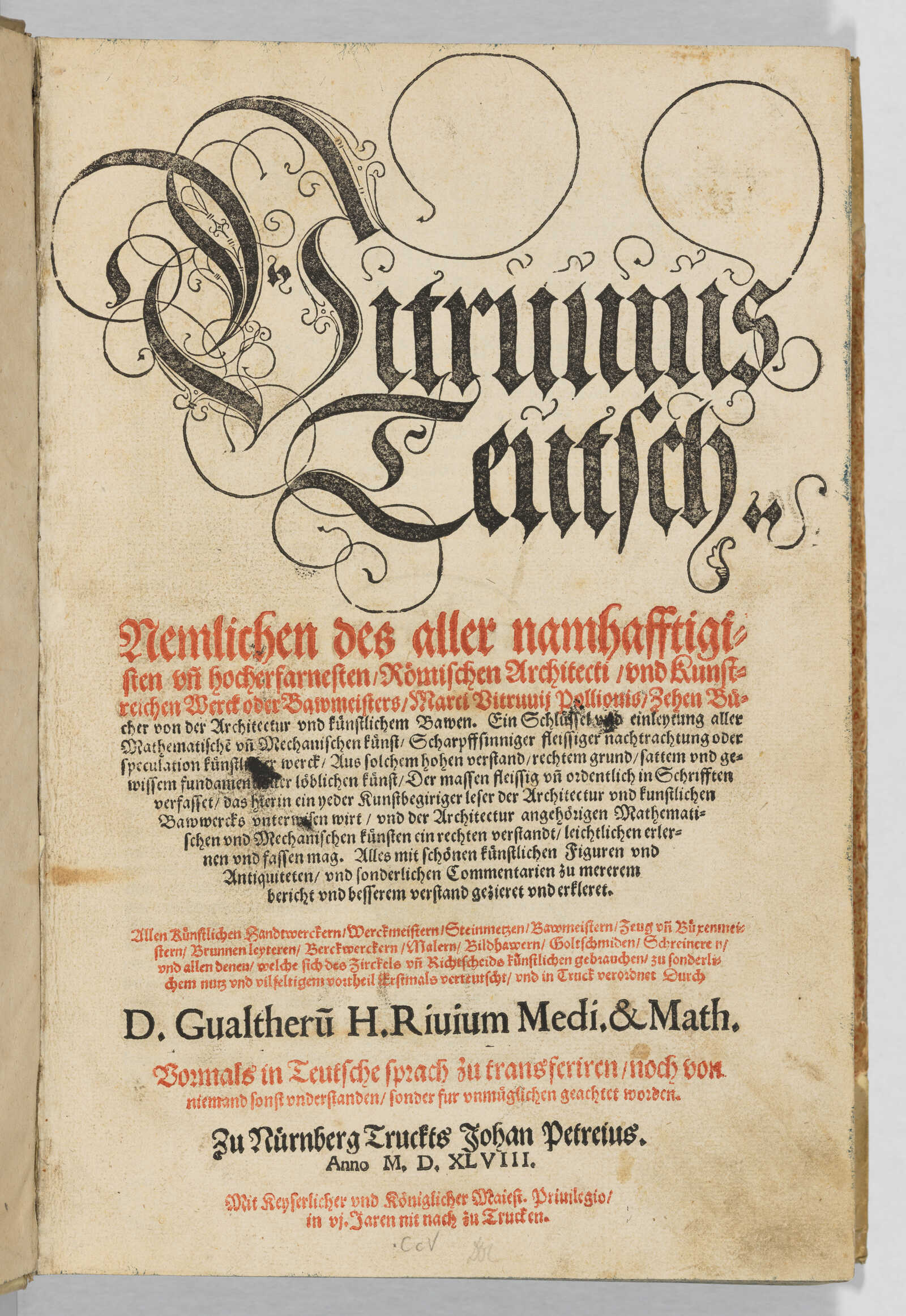

Vitruvius: The Roman Who Shaped Modern Architecture

Vitruvius wasn’t Rome’s most famous architect—but he gave architecture its voice. His treatise De Architectura did more than codify how to build; it taught Rome how to think about building.

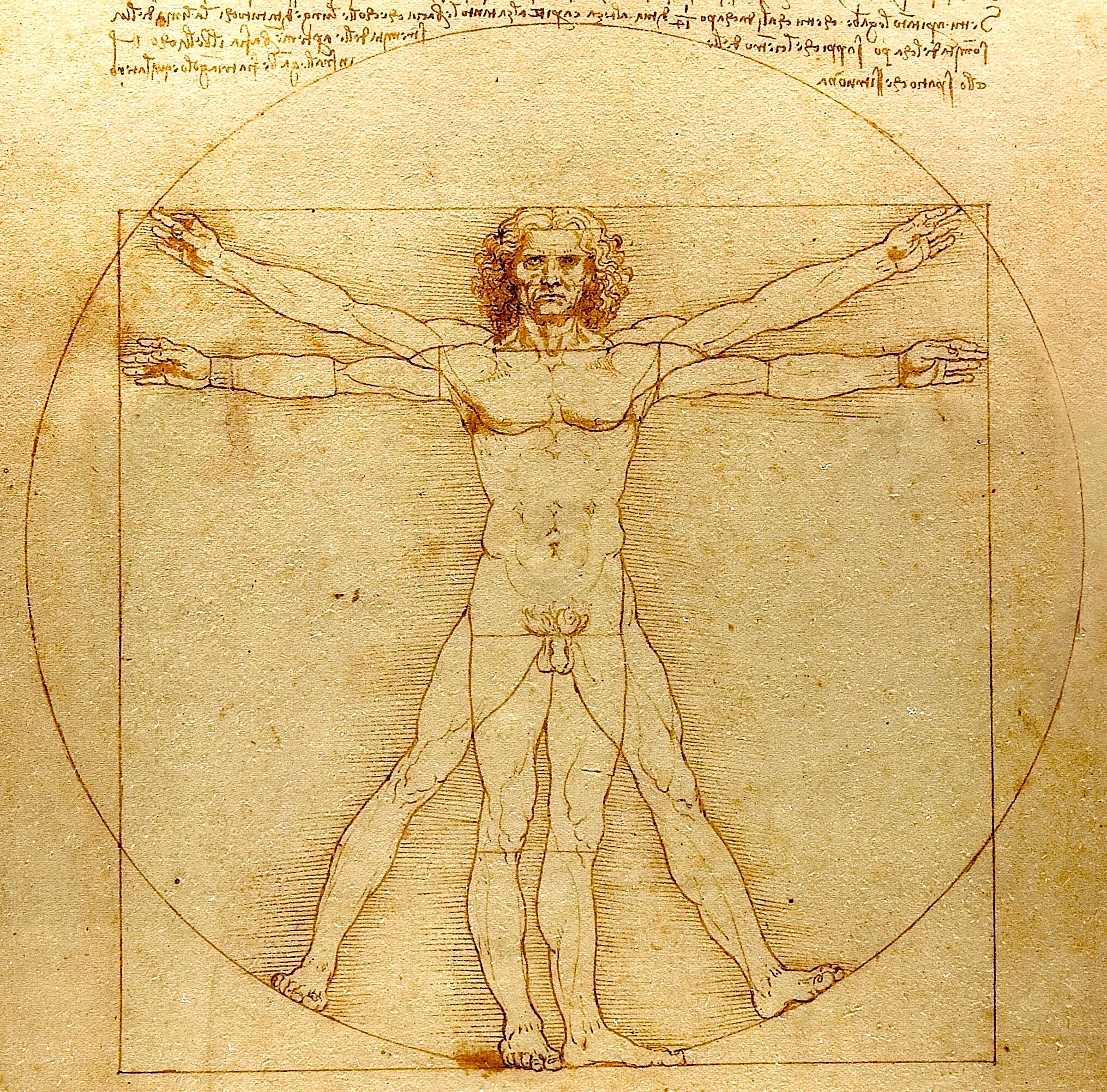

Vitruvius, a Roman architect and engineer writing in the 1st century BCE, offered more than a construction manual in his ten-book treatise De Architectura. He laid down a philosophy: that buildings should stand firm (firmitas), serve their purpose (utilitas), and delight the senses (venustas).

With this deceptively simple triad, he shaped not just Roman infrastructure but the entire Western architectural canon. From aqueducts to domes, Renaissance drawings to neoclassical facades, the fingerprints of Vitruvius are still everywhere—etched into stone, and into thought.

Vitruvius, the Enigma

The true shape of Vitruvius—his biography, chronology, and professional status—remains tantalizingly obscure. In his landmark study, “The Date, Identity, and Career of Vitruvius”, Barry Baldwin surveys the fragmented and often contradictory scholarship around this Roman architect, arguing that much of what is said about Vitruvius is either speculative or based on ambiguous internal evidence from De Architectura. Still, by examining the text alongside secondary sources, Baldwin reconstructs the most likely contours of Vitruvius’s life and intentions.

Dating De Architectura

There is no direct external evidence to pinpoint the exact date when De Architectura was written. However, scholars have tried to estimate its composition using indirect clues from within the text.

Some believe the treatise was written over an extended period, but Barry Baldwin cautions against reading too much into Vitruvius’s internal cross-references as proof of that. For example, F. Granger, editor of the Loeb edition, thought that Vitruvius published individual books one at a time. His argument relies on lines like:

“But if anyone wants to dispute the order of this book…”

and:

“In this volume I have written… in the next volume I will explain”.

But Baldwin argues these are likely just references between sections of a single cohesive work—not proof of staggered publication. A firm terminus post quem (earliest possible date) is provided by a reference to the Alpine kingdom of Cottius, which would have been inaccurate after Nero turned the area into a Roman province.

Even more tellingly, the preface to Book I makes clear that Julius Caesar is already dead and deified, and that his adopted son, Octavian (later known as Augustus), is now the uncontested ruler of the Roman world.

Scholarly opinions differ widely:

- E. Rawson believes most of the treatise was written in the early 30s BCE, with a final dedication to Augustus sometime in the 20s.

- F. Granger argued that it must have been completed before 27 BCE, pointing to the fact that Vitruvius never uses the title “Augustus.”

- Ronald Syme, by contrast, places its completion shortly after 27 BCE.

- Teuffel-Schwabe dates the text to around 14–13 BCE but no later than 11 BCE.

But this is not only a question of chronology—it’s also about ideology. Was Vitruvius a Republican in spirit, writing with nostalgia for the old order? Or was he fully part of the emerging Augustan age? Rawson tends to see him as a late Republican; Teuffel-Schwabe firmly places him among Augustan thinkers.

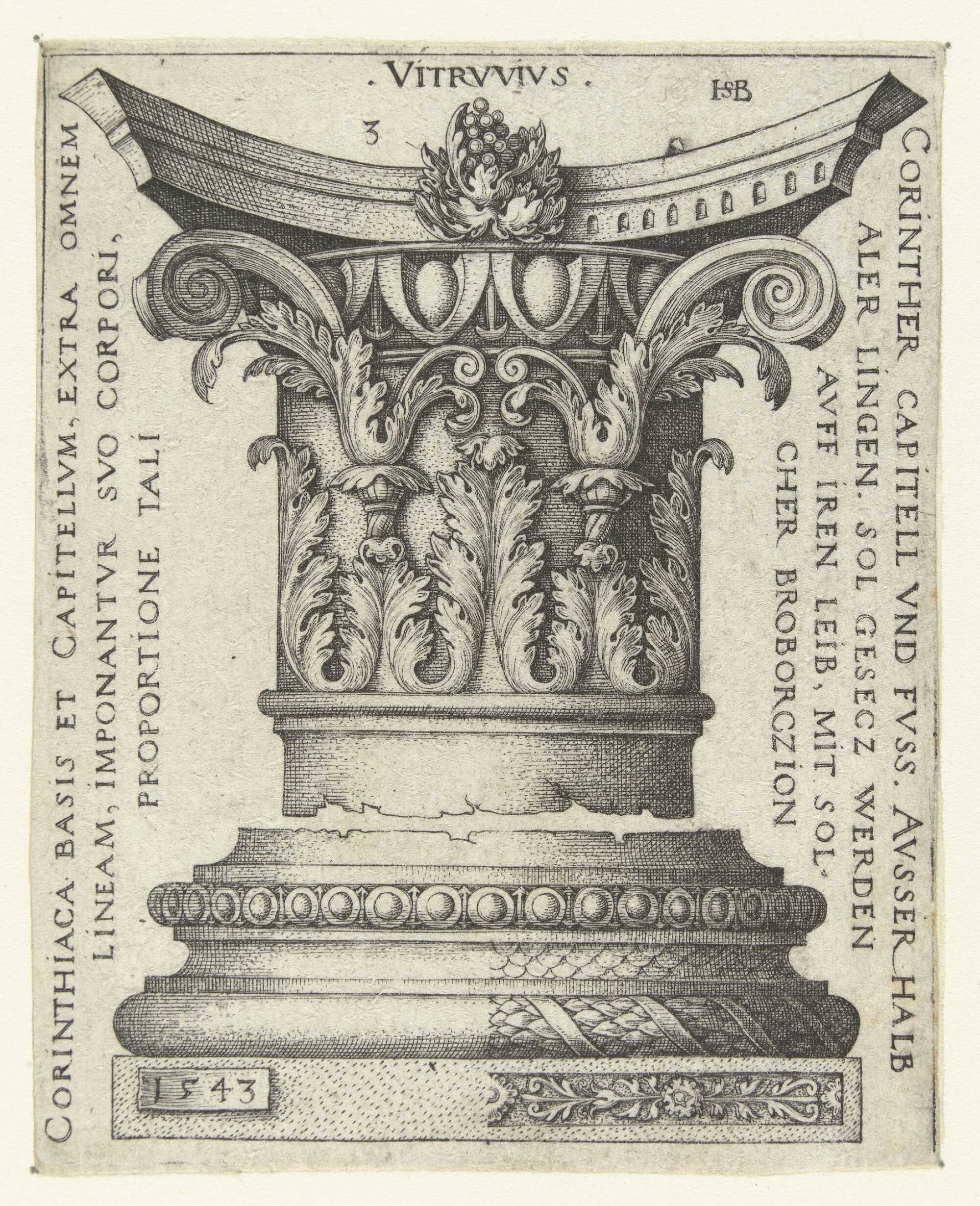

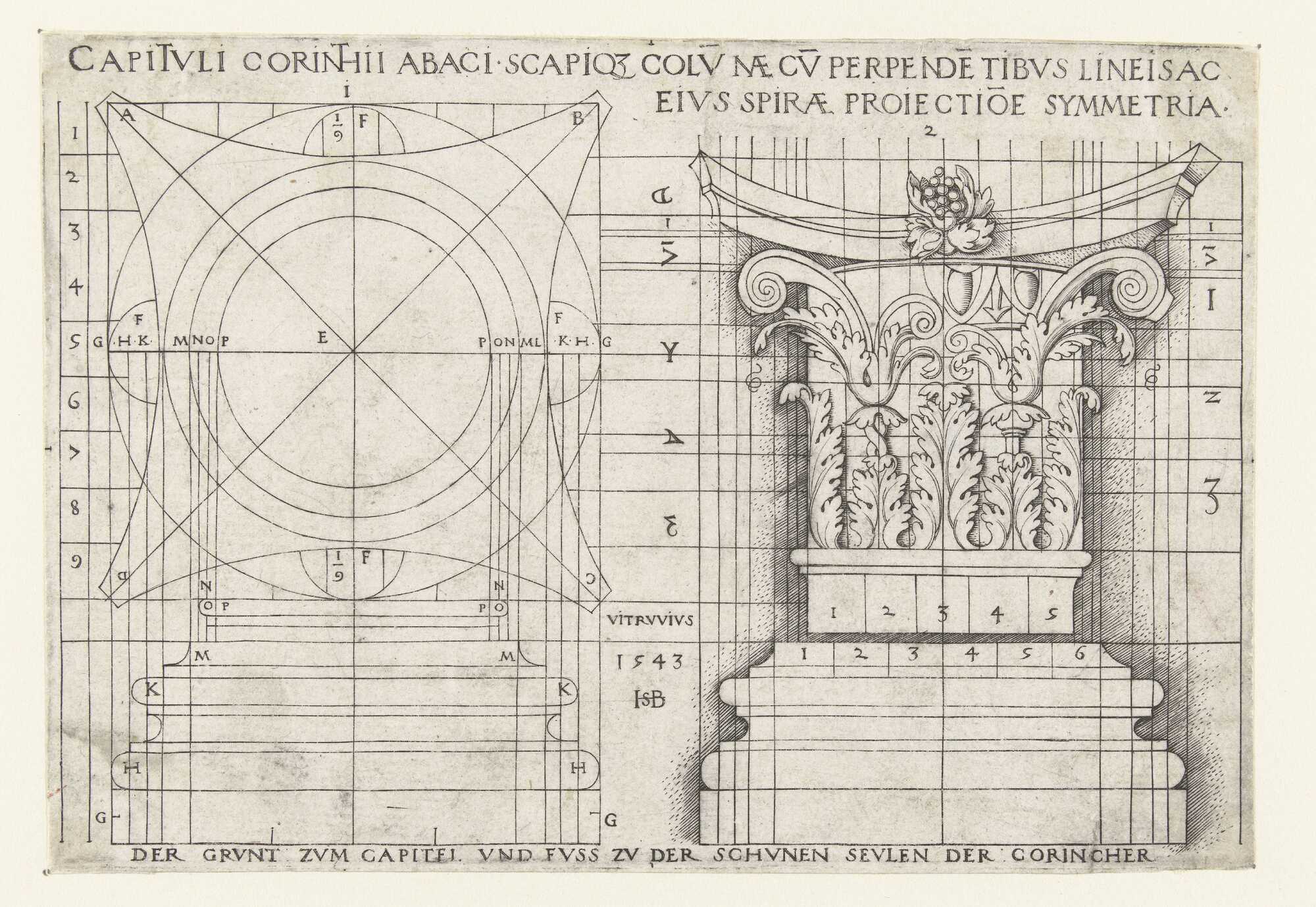

Sheets with the mapping, capital and basement of a Corinthian column after Vitruvius. Public domain

Style, Politics, and the Elision of the Triumviral Period

Rawson bases her early dating partly on Vitruvius's reference to Faberius and Vestorius—two men active in the 40s BCE but with no clear mention of the Triumviral period. Faberius, mocked for his garish taste in home decoration, had also forged documents for Mark Antony.

Vestorius, the owner of a notable dye works in Puteoli, was a friend of Cicero. Baldwin notes that these mentions may reflect Vitruvius’s desire to flatter Augustus or to erase awkward political memories. The absence of direct reference to the Triumvirate might well align with Augustus's own erasures of that divisive era.

The idea that Vitruvius deliberately avoided using the title “Augustus” is probably overstated. Baldwin points out that Vitruvius’s tone of praise—especially in the opening of Book I—is fully in line with Augustan political language and may even have anticipated it.

He begins with:

“Since your divine mind and spirit, Commander Caesar…”,

echoing the kind of reverence we later see in Augustan propaganda. Baldwin also draws attention to the similarities with Horace’s Epistles, which opens:

“Since you alone shoulder so many burdens and so many affairs…”,

and with Augustus’s Res Gestae, where he refers to gaining control:

“over the empire of the whole world”.

As Baldwin puts it,

“Vitruvius may have helped set the tone for the Augustan poets.”

The Basilicas, the Provinces, and the Question of Date

Another dating clue is found in passage 5.1.6, where Vitruvius claims to have built the basilica at Fanum Fortunae. Granger defends the authenticity of this passage, which some earlier critics had questioned. Since Fanum is probably an Augustan foundation, this activity reinforces a post-27 BCE context.

Vitruvius’s statement that:

“the state was enlarged with provinces through you”

may refer to the additions of Egypt, Galatia, or the reorganization of the Spanish provinces—all of which took place between 27 and 25 BCE. Baldwin treats this as further support for a late 20s BCE composition.

Elsewhere, Vitruvius speaks of Lucretius, Cicero, and Varro as authors with more enduring authority than their contemporaries. Since Varro died in 27 BCE, the passage must have been written afterward.

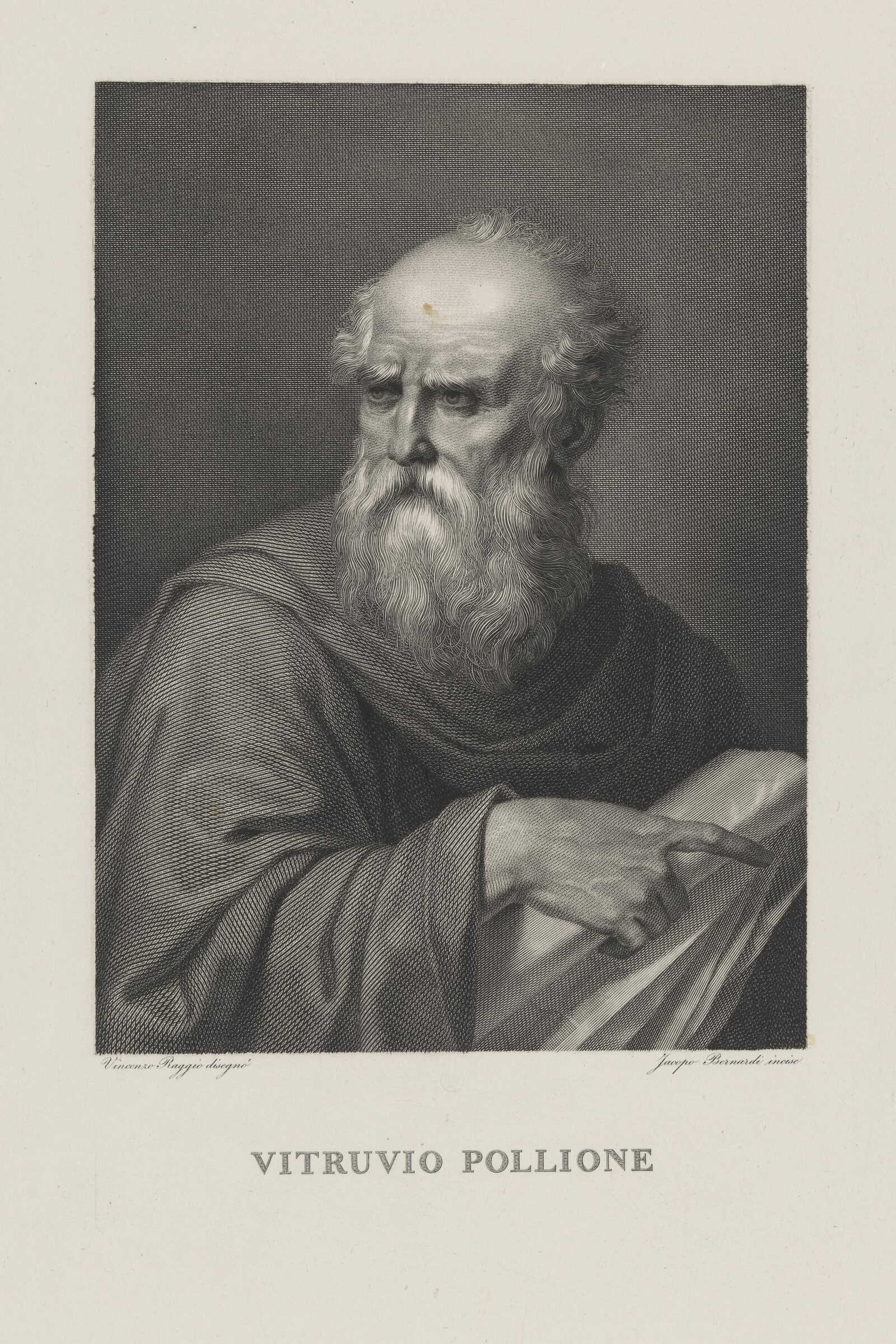

Name and Identity of Vitruvius

The full name “Vitruvius Pollio” is not securely attested in ancient sources. Manuscripts refer to him simply as “Vitruvius.” The name “Pollio” appears in the later epitome by Faventinus, who wrote “Vitruvius Polio and other authors.” Baldwin entertains Granger’s suggestion that “Polio” may refer instead to Asinius Pollio, suggesting that Faventinus might be listing two separate authors.

Another fringe theory identifies Vitruvius with Mamurra, Caesar’s notoriously decadent praefectus fabrum. Baldwin finds this unconvincing: Vitruvius never claims any special intimacy with Caesar—only that he had been “notus”-known. Furthermore, the Mamurra of Catullan invective is hard to reconcile with the frugal, technocratic Vitruvius, who emphasizes cost-efficiency and modesty.

Was He African?

Some inscriptions and grammatical oddities once led scholars to place Vitruvius in Africa, but Baldwin convincingly argues for an Italian origin. Vitruvius shows deep affection for the Italian landscape: Pozzolana quarries, Appennine sands, Amiternum stone, and curative waters at Ardea and Velia all receive detailed attention.

He praises Italian wines, discusses Roman engineering, and rarely shows the same intimacy with foreign regions. While he recounts a conversation with Gaius Julius, son of Massinissa, and offers a memorable epigram—Africa parens et nutrix ferarum bestiarum— Africa, mother and nurse of wild beasts , his tone is detached, even ironic.

Baldwin concludes that Africa was not Vitruvius’s homeland, and his knowledge of the East likely came from firsthand travel, especially to cities like Ephesus. Despite the uncertainties around his life, Vitruvius does leave us one personal sketch. At the opening of Book II, Vitruvius presents himself as old, ugly, and frail:

“staturam non tribuit natura, faciem deformavit aetas, valetudo detraxit vires”

Nature did not grant me stature, age disfigured my face, and poor health took away my strength.

He remembers his parents with affection, grateful for their provision of both literary and practical education. His admiration for Cicero, Lucretius, and Varro is evident throughout De Architectura. He echoes Lucretius on atoms and humanity’s evolution, and quotes Cicero directly in places.

Despite his ambitions, Vitruvius never exaggerates his status. Of Julius Caesar he writes only “I had been known [to him]”, and he attributes his career stability to the patronage of Augustus’s sister—likely Octavia, who died in 11 BCE. This suggests a terminus ante quem—the latest possible date.

His duties, ambiguously described as “recognitionem”—the duty of inspection, may refer to surveying or military engineering. Baldwin emphasizes that we do not fully understand the job title—Latin dictionaries treat recognitio inconsistently—and we cannot determine whether Vitruvius held a civic or strictly military role.

Baldwin closes with a note of intellectual humility. Despite the abundance of modern theories, “Vitruvius ultimately remains an enigma.” He occupies a space between practice and theory, Republican ideals and Augustan politics, artisan and rhetorician.

What emerges from De Architectura is not a memoir, but the voice of a man who sought to raise architecture to a disciplined, dignified profession—one supported not by rank or spectacle, but by order, discourse, and memory. (The Date, Identity, and Career of Vitruvius, by Barry Baldwin)

Vitruvius and the Invention of Architectural Discourse

Vitruvius’s De Architectura, written around 30 BCE, stands as the oldest surviving treatise on architecture. Unlike other ancient technical writings, it was unique in grounding architectural practice in abstract, predominantly Greek metaphysical concepts. This philosophical ambition is likely what ensured its preservation into the modern era—while other architectural treatises were lost, Vitruvius’s survived.

Ironically, in the actual field of architecture, its influence has been modest. During the Renaissance, more attention was given to the later and more narrowly technical writings of Palladius Rutilius Taurus Aemilianus (c. 400 CE), whose straightforward approach resonated more with the practical needs of the time.

Architects, like writers of any craft, tended to prefer sources that reflected their own stylistic and intellectual priorities. Palladius's limited scope may have offered more appeal to Renaissance minds than Vitruvius’s philosophical complexity.

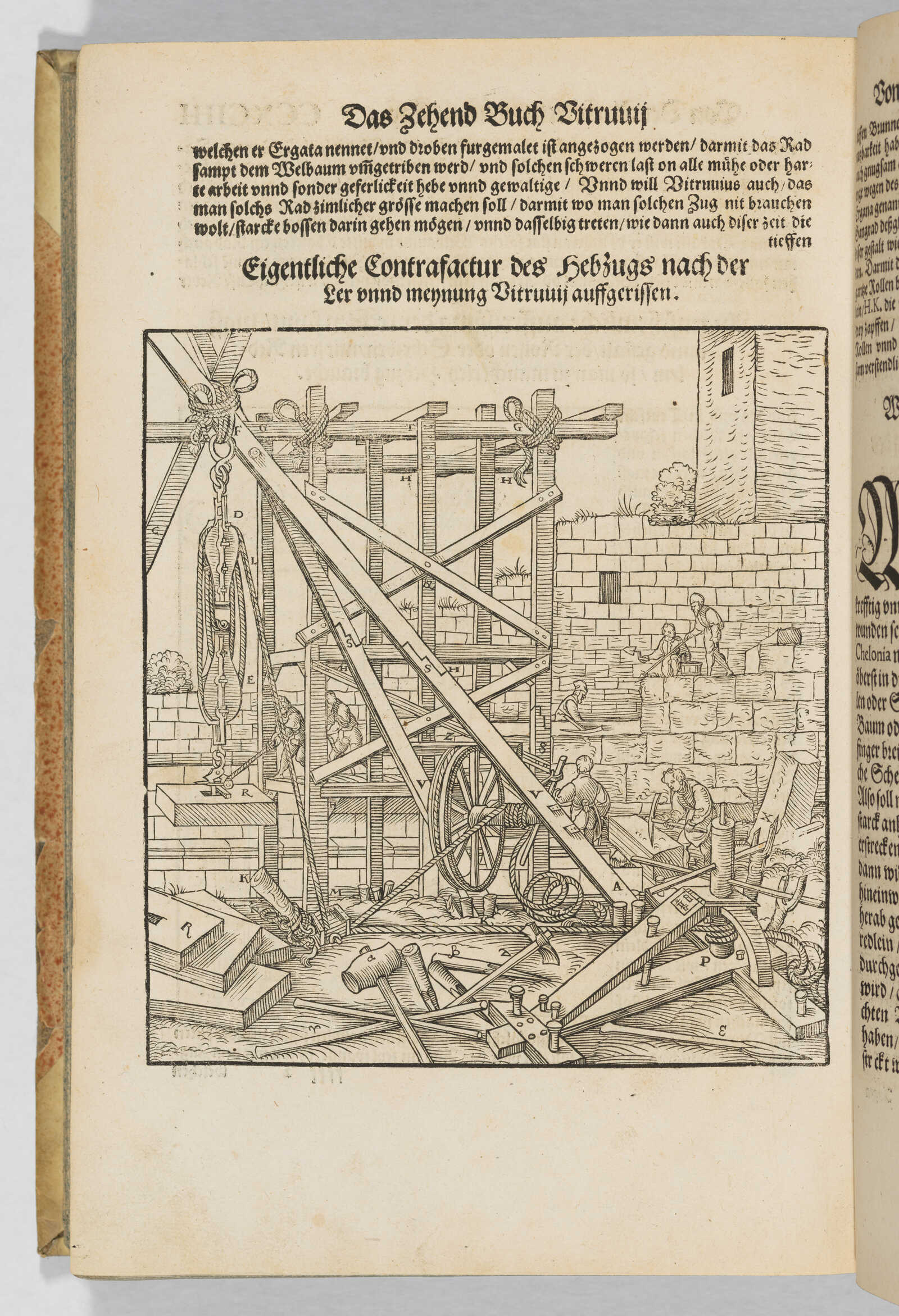

A Rhetorical Shift: Technology as Language, Not Law

Vitruvius’s real legacy lies not in his impact on building techniques but in the literary form he gave to architecture. De Architectura stood out as a textual model—discursive yet occasionally systematic, formal and critically engaged. In this, it helped shape what would become the modern understanding of “technology”—not as a natural consequence of necessity, but as a mode of thinking governed by systems of justification and external criteria.

Technology, as presented in Vitruvius’s text, did not emerge purely from practical knowledge or theoretical science. Instead, it took shape through the framing of making as a discursive subject, reliant on conventions and rhetorical structures. His work anticipated the idea of technical knowledge as something constructed through language, not simply discovered through experience.

This approach challenged the assumption that technology is rooted in scientific autonomy. Vitruvius’s writing reveals that technology does not arise from immutable laws or metaphysical certainties but rather from the deliberate codification of practice through discourse.

While such knowledge may seem grounded in practical understanding, it is often fragmented, borrowed, or indirect. His work implies that what we now call “technology” is not a body of objective knowledge but a cultural device shaped by human intention and expression. The systematization of technical activity was not about uncovering universal truths but about introducing these activities into the realm of language, argument, and evaluation.

Architecture Enters the Latin World

Critics of Vitruvius have long focused on his peculiar use of language. Even in the 15th century, Leon Battista Alberti noted that his Latin felt foreign to both Greek and Roman readers. Many historians have remarked that the Latin of De Architectura is at times barely Latin at all.

Yet what his style lacked in elegance, it aimed to recover through purpose. His rhetorical strategy was not accidental. Following Cicero’s guidance on stylistic propriety, Vitruvius seems to have selected a register that matched the practical, grounded subject of architecture.

One of his 20th-century translators we aforementioned, Frank Granger, observed that his language closely resembled everyday spoken Latin, similar to graffiti found in Pompeii. Despite his repeated apologies for his lack of literary polish, Vitruvius demonstrates mastery over his content. His use of rhetorical structure and Stoic moral concepts—like decor (appropriateness)—shows his intention to frame architectural judgment as a matter of ethical and stylistic choice.

Vitruvius did not merely compile a building manual.

His inclusion of critical values reveals a more ambitious project.

Earlier architectural texts, such as those by the Greek architect Hermogenes, were likely reference manuals—lists and diagrams designed for trained practitioners, often rooted in the scholarly traditions of the Alexandrian Museum.

Vitruvius certainly inherited and borrowed from these Greek precedents, as shown by the Greek terminology he retained and the evident presence of lecture-style passages in his work.

But his goal was different.

He sought to create a Latin architectural vocabulary and a coherent framework for practice. While his technical explanations were often inconsistent and sometimes obscure—leading many later historians to frustration—his primary innovation was not in providing precise geometric instructions but in establishing the rhetorical and conceptual scaffolding for architecture as a public discipline.

From Manual to Manifesto

The significance of De Architectura lies not in its technical content but in its rhetorical strategy. Rather than guiding practical design in a direct way, Vitruvius set out to bring architecture into the sphere of public Latin discourse.

Before him, architecture was largely excluded from mainstream Roman intellectual life. Its elements lacked proper terminology and theoretical structure. Without such language, Vitruvius argued, one could not form judgments based on decor or produce meaningful narratives—what he called historia.

His treatise aimed to correct that absence. Only after establishing this new discursive framework did he turn to the more detailed concerns of proportion, measurement, and construction.

His ambition becomes even clearer when considering the circumstances under which he wrote. In the introduction to De Architectura, as already mentioned, Vitruvius states that he as already an old man, formerly known to Julius Caesar and supported by Octavia, the sister of Augustus.

He had worked in civil architecture and was financially secure in retirement. He wrote not for money, but to promote his name and to argue for higher standards in Roman building practice. His treatise was a polemic disguised as a technical guide—a contribution to Augustus’s civic reforms, framed as a formal intervention in the discourse of the age. To elevate Roman architecture, one did not simply list techniques; one needed a rhetorical intervention that could resonate with elite readers and shape the intellectual framework of civic life.

The Real Legacy: Writing as Technology

In this light, De Architectura emerges as a work not of architectural metaphysics, but of architectural language. Its true contribution to Western history lies in its transformation of building into discourse.

The book’s significance does not reside in its metaphysical claims or technical rules—these were common enough in antiquity. What was truly innovative was its use of rhetorical and linguistic values to evaluate and organize the built environment. It was the creation of a new kind of public, reflective architectural expression.

By opening the language of architecture to critique, judgment, and structured argument, Vitruvius invented the template for all future technical writing. He redefined architectural practice not through diagrams or dogma, but through the grammar of discourse.

In doing so, he subverted the esoteric nature of earlier building knowledge. His rhetorical structure dissolved secrecy and invited participation, bringing technical practices into an elitist but visible public sphere.

The criticism often aimed at the book’s loose structure—its shifts in topic, its lack of clear headings—misses the point. De Architectura was never meant to be a simple instructional text. It was a codification of how architecture might be made intelligible to reasoned debate.

It echoed the structure of a rhetorical treatise, ascending in complexity and seeking to persuade not just through content, but through the very act of articulation. In this, Vitruvius did not merely record how buildings were made—he showed how building itself could become a way of thinking. (What Vitruvius Said, by Richard Patterson)

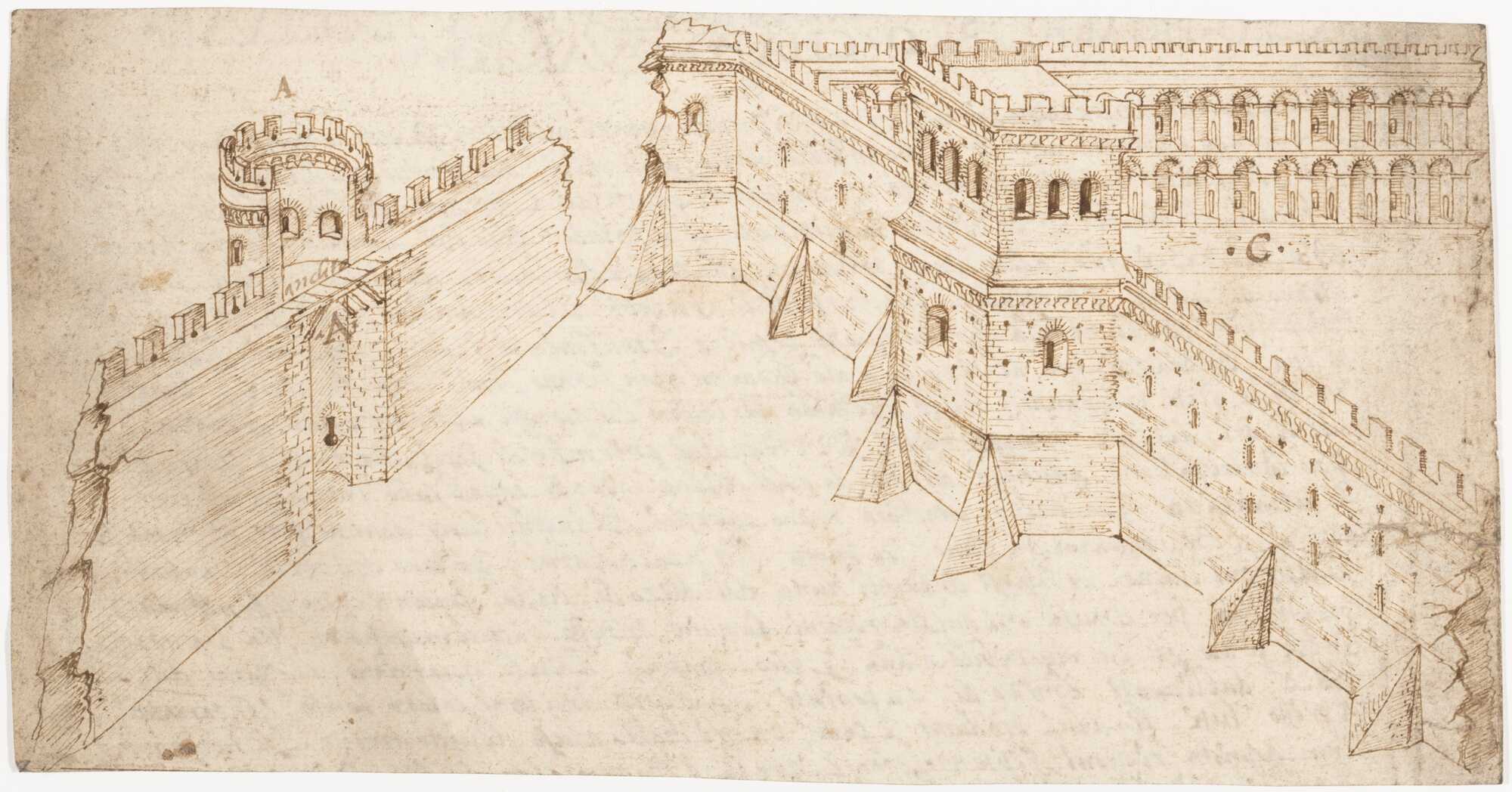

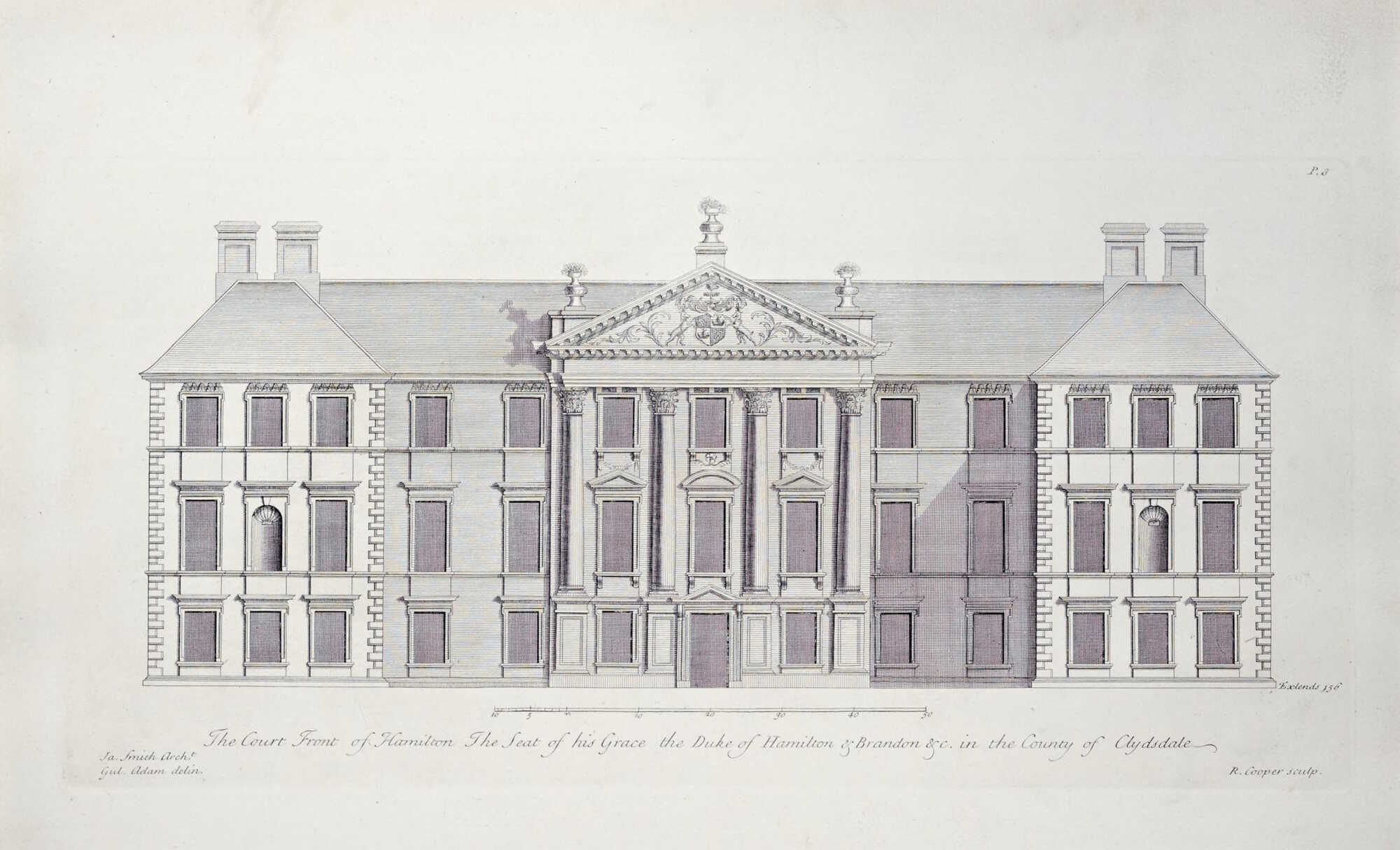

Image #1: From Vitruvius Scoticus, Hamilton Palace South (Court) Front

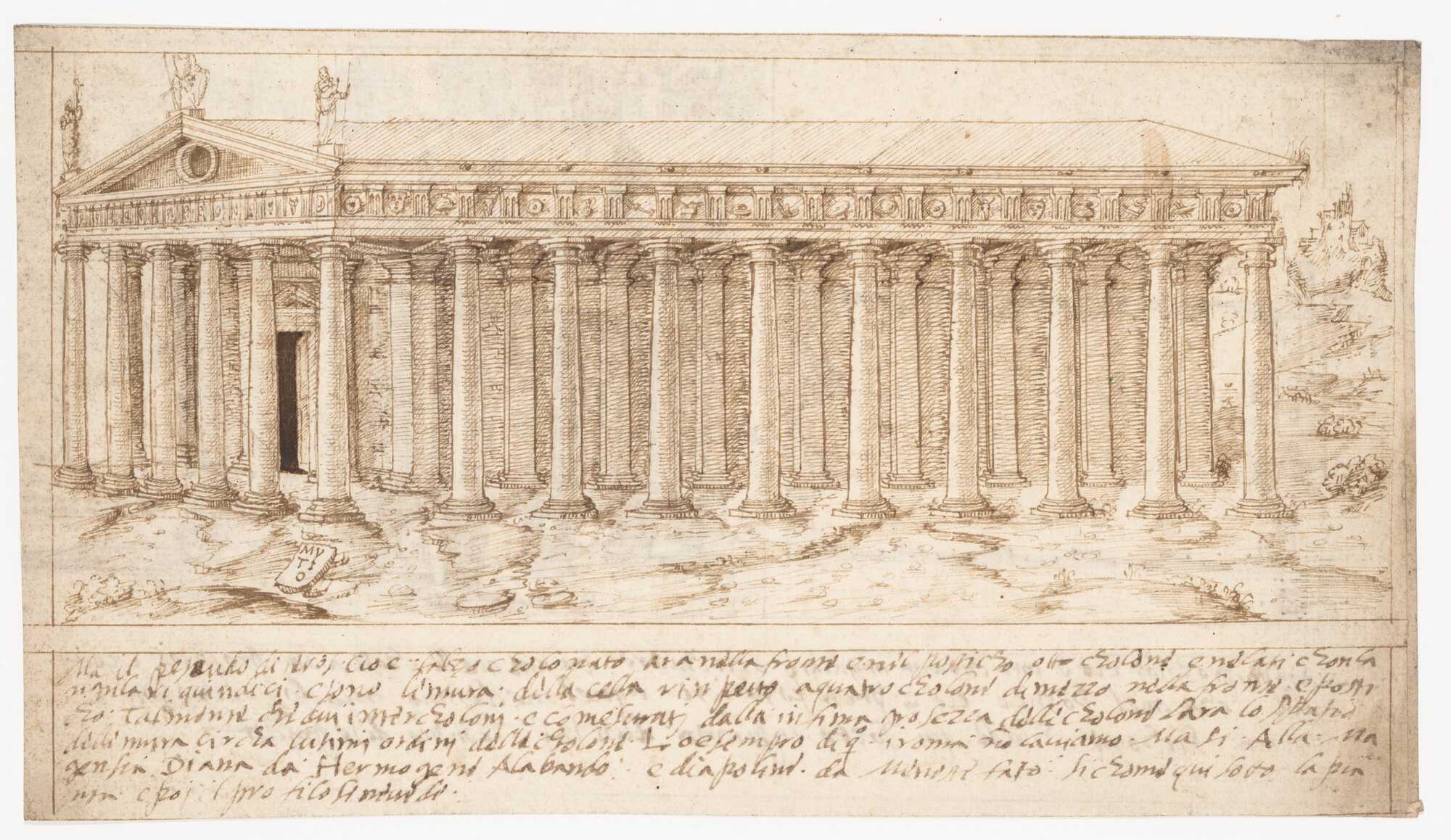

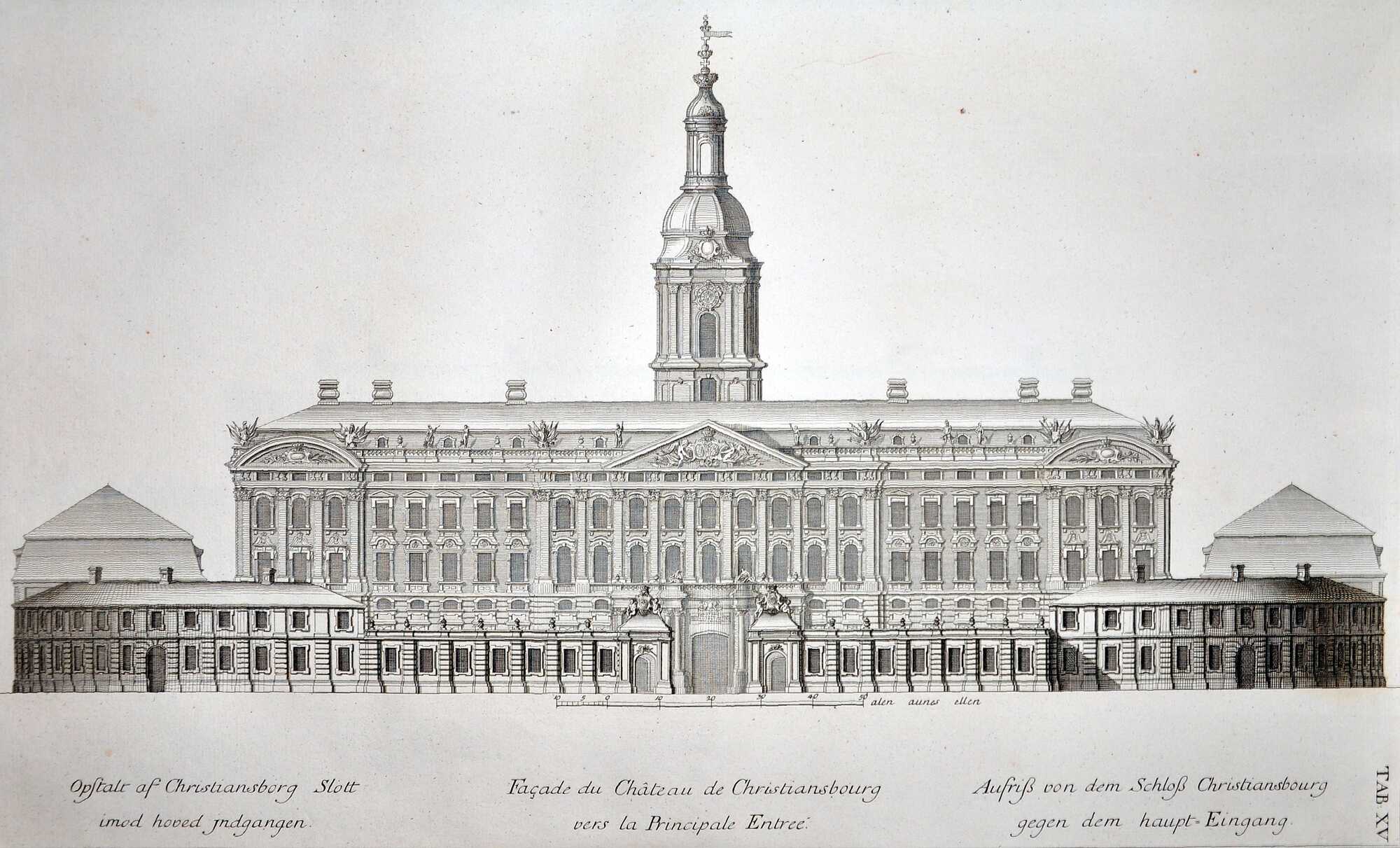

Image #2: From Vitruvius Danske, Facade of Christiansborg Castle to the Main Entrance

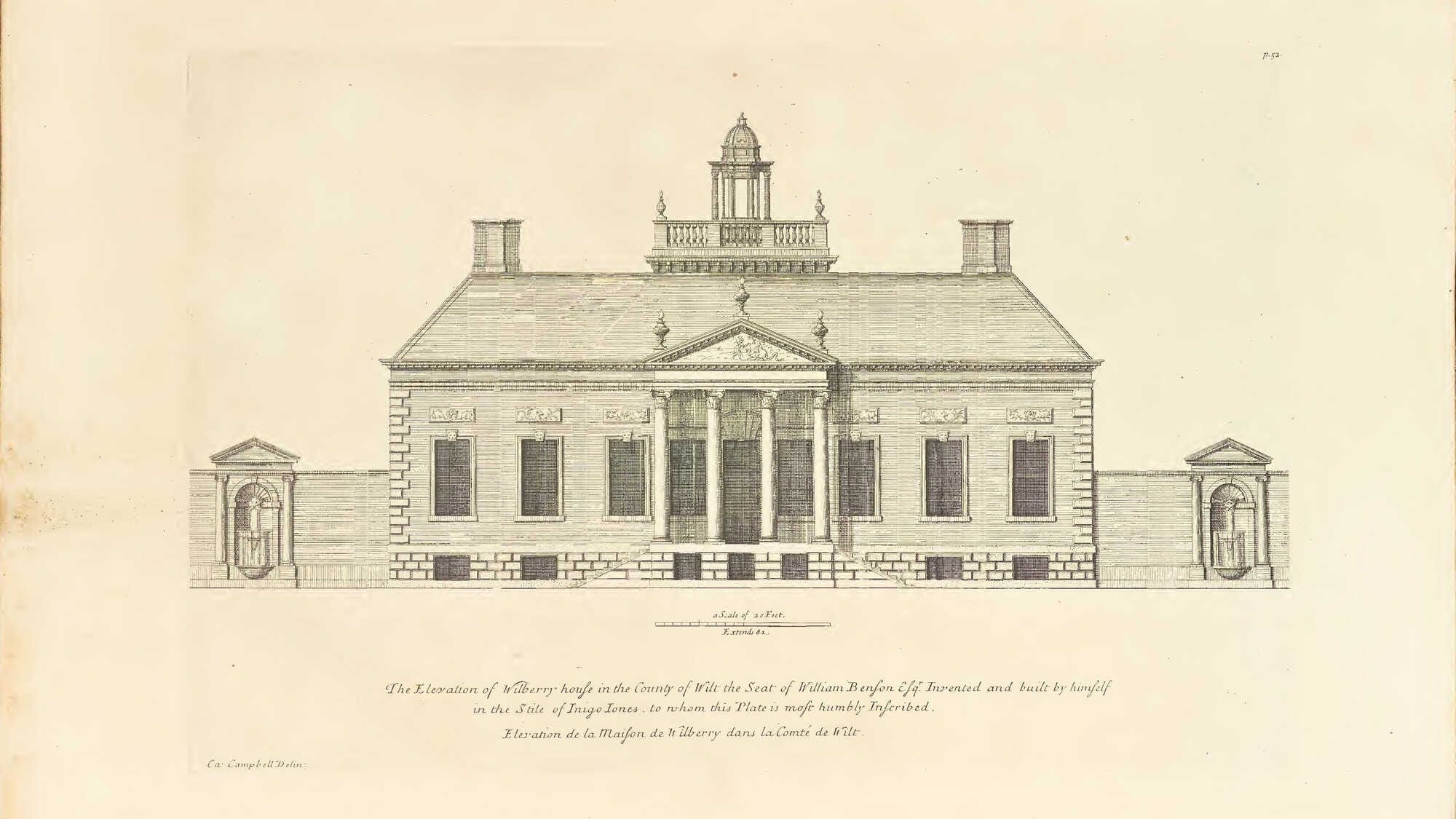

Image #3: From Vitruvius Britannicus, the Elevation of Wilberry House in the County of Wilt, the Seat of William Benson

All images are Public domain

What eventually endures in Vitruvius is not a catalogue of construction techniques but a vision of architecture as a civic and intellectual discipline. He transformed building into something that could be argued, judged, and remembered—shifting it from the hands of artisans into the realm of cultural memory.

De Architectura is not just the first architectural treatise we possess; it is the first to insist that the act of building belongs in language, that the shaping of cities is inseparable from the shaping of thought. In this way, Vitruvius did not simply write the rules—he invented the conversation.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: