The Roman Cookbook That Reveals an Empire

More than a gourmand, Apicius became a name that absorbed generations of Roman cooks. De Re Coquinaria is not a single author’s work, but the most complete survival of ancient kitchen practice, preserved under a reputation built on excess.

He is remembered less as a person than as a warning. In Roman literature, his name came to stand for excess without limit, appetite without restraint, and a refusal to accept moderation at the table. Ancient writers returned to him again and again, not to praise skill, but to illustrate what happened when wealth, power, and taste were allowed to feed upon themselves. Yet the figure so vividly sketched in satire and moral critique is only loosely connected to the Roman cookbook that later carried his name.

The Many Apicii and the Making of a Reputation

Marcus Gavius Apicius is inseparably associated with Roman cookery through the collection known as De Re Coquinaria, traditionally linked to his name. Yet despite this enduring association, the historical figure behind the name remains elusive. What survives about Apicius himself consists largely of anecdote: stories that emphasise excess, luxury, and an almost theatrical devotion to food, culminating in an equally extravagant death. Ancient sources, moreover, do not speak of a single Apicius, but of three men bearing the name, each remembered for culinary indulgence.

The earliest Apicius lived at the turn of the first century BCE and was already proverbial for extravagance. He appears in Posidonius’ Histories, preserved by Athenaeus, as a figure who surpassed all others in prodigality:

“a man who transcended all in prodigality” Athenaeus, The Dinner of the Sophists

The second—and the one with whom this discussion is primarily concerned—is Marcus Gavius Apicius, active during the reign of Tiberius in the early first century CE. A third Apicius appears in the second century CE under Trajan and is remembered not for recipes but for technical ingenuity in food preservation. Athenaeus records his invention of specialised oyster packaging during Trajan’s Parthian campaign:

“When the Emperor Trajan was in Parthia, at a distance of many days’ journey from the sea, Apicius caused fresh oysters to be sent to him in packing skilfully devised by himself.” Athenaeus

A bon viveur with a provocative death

Marcus Gavius Apicius flourished in the early imperial period and became the archetype of the bon viveur. His reputation was such that his name itself became shorthand for wealth and gastronomic excess. Ancient writers consistently emphasise not only his luxurious habits in life but the calculated extravagance of his death. Martial famously framed Apicius’ suicide as the ultimate act of gluttony:

“Apicius, you had spent 60 million [sesterces] on your stomach, and as yet a full 10 million remained to you. You refused to endure this, as also hunger and thirst, and took poison in your final drink. Nothing more gluttonous was ever done by you, Apicius.” Martial, Epigrams

Cassius Dio likewise records the episode, presenting Apicius’ decision as an unwillingness to live on what he considered insufficient means:

“Apicius so far surpassed mankind in prodigality that when he wished to know how much he had already spent and how much he still had left, on learning that 10 million [sesterces] still remained to him, he became grief-stricken, and feeling that he was destined to die of hunger, he took his own life.” Cassius Dio, Roman History

Direct evidence for Apicius’ culinary activity is limited. A contemporary grammarian, Apion, authored a treatise entitled On the Luxury of Apicius, now lost apart from its title (Athenaeus). In its absence, Pliny the Elder preserves several details of Apicius’ gastronomic innovations. Among these is the claim that Apicius promoted the consumption of flamingo tongues:

“Apicius, the most gluttonous gorger of all spendthrifts, taught that flamingo’s tongue has a particularly fine flavour.” Pliny, Natural History

Flamingos, originally imported from Africa as luxury food, were later bred in Italy to satisfy elite demand. Martial notes their presence on elite estates, such as Faustinus’ farm at Baiae (Epigrams). Although De Re Coquinaria includes a recipe for boiled flamingo in spiced date sauce, it does not specify tongues. Nevertheless, references by Seneca and Martial demonstrate that Apicius’ recommendation was widely taken up.

Flamingo tongues later featured among the ingredients of Vitellius’ infamous dish, the Shield of Minerva, and the practice was further elaborated under the emperor Elagabalus, who served peacock and nightingale tongues at imperial banquets.

Another culinary innovation attributed to Apicius concerns the treatment of pork liver:

“There is also the art of treating the liver of sows like that of geese, the discovery of Marcus Apicius. The pigs are stuffed with dried figs, and when full, they are killed after having been given a drink of mulsum.” Pliny, Natural History

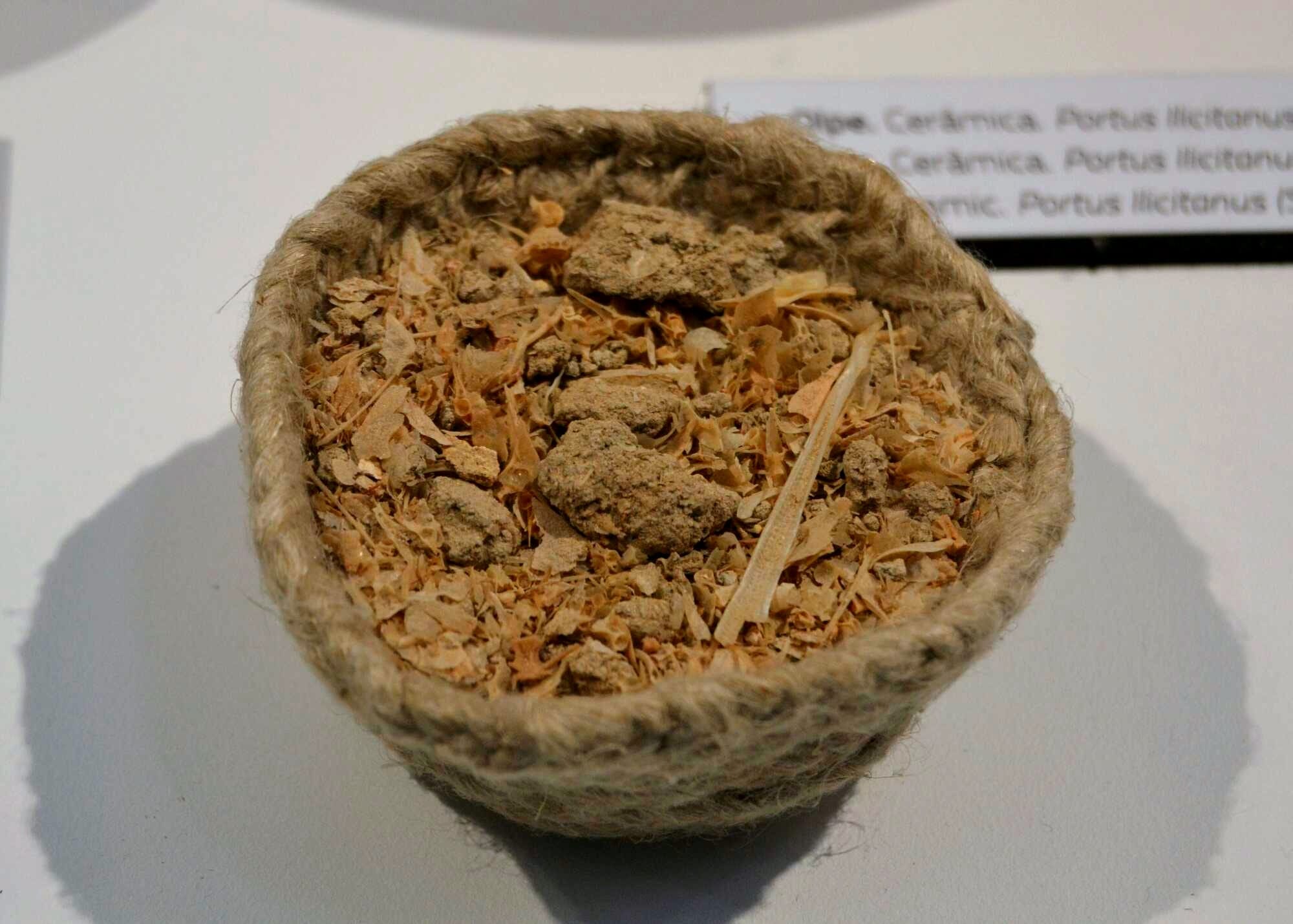

Foie gras was already known in Roman cuisine, with Pliny attributing its discovery to earlier figures (Natural History). Apicius’ contribution lay in adapting this technique to pigs, producing ficatum, liver flavoured through controlled feeding. De Re Coquinaria preserves two recipes for this dish (7.5.1–2), combining pepper, thyme, lovage, liquamen, wine, oil, and laurel berries.

Pliny also records Apicius’ preference for red mullet prepared in elaborate sauces:

“Marcus Apicius, a man born for every device of luxury, thought mullets excellent when killed in a sauce of their companions (garum sociorum), and also allec (fish paste) made out of their livers.” Pliny, Natural History

Garum, a fermented fish sauce, was a prized condiment in elite Roman cuisine. Garum sociorum, imported from New Carthage in Spain, represented the highest grade. Pliny’s phrasing allows a deliberate ambiguity: socius could mean either a commercial association or, humorously, the fish’s “companions.” Allec, originally a by-product of garum production, later became a luxury food in its own right, particularly when made from mullet liver or shellfish (Natural History).

The prestige attached to red mullet is illustrated by Seneca, who describes an auction orchestrated by Tiberius himself:

“Tiberius Caesar ordered a mullet of enormous size that had been sent to him to be sent to the market and put up for sale… Caesar said, ‘Friends, I shall not be surprised if either Apicius or Publius Octavius buys that mullet.’ … Octavius was victorious… since he had purchased for 5,000 sesterces a fish which Caesar had sold and which not even Apicius had succeeded in buying.” Seneca, Epistles

Apicius’ pursuit of seafood excellence extended beyond Italy. Athenaeus recounts his aborted journey to Libya in search of superior shrimps:

“There lived in the days of Tiberius a man named Apicius… He had spent countless sums on his belly at Minturnae… When he heard that they also grew to excessive size in Libya… On seeing the shrimps, he enquired whether they had any that were larger… and ordered the helmsman to sail back to Italy by the same route, without his even having approached the Libyan shore.” Athenaeus

Such anecdotes collectively present Apicius as a wealthy Roman whose culinary curiosity extended to the exotic and the extreme. Seneca generalises this tendency in a broader moral reflection:

“Behold Nomentanus and Apicius, digesting… the creatures of every nation upon their table.” Seneca, On the Happy Life

Ancient sources attribute two cookery works to Apicius: a general cookbook and a specialised treatise on sauces. There is no firm evidence that he was a professional chef. Tacitus instead describes him simply as a wealthy and prodigal man (Annals). His reputation attracted both admiration and moral condemnation. Seneca remarks sharply that Apicius,

“learned in the science of the cook-shop,”

had

“defiled the age with his teaching” (To Helvia, On Consolation).

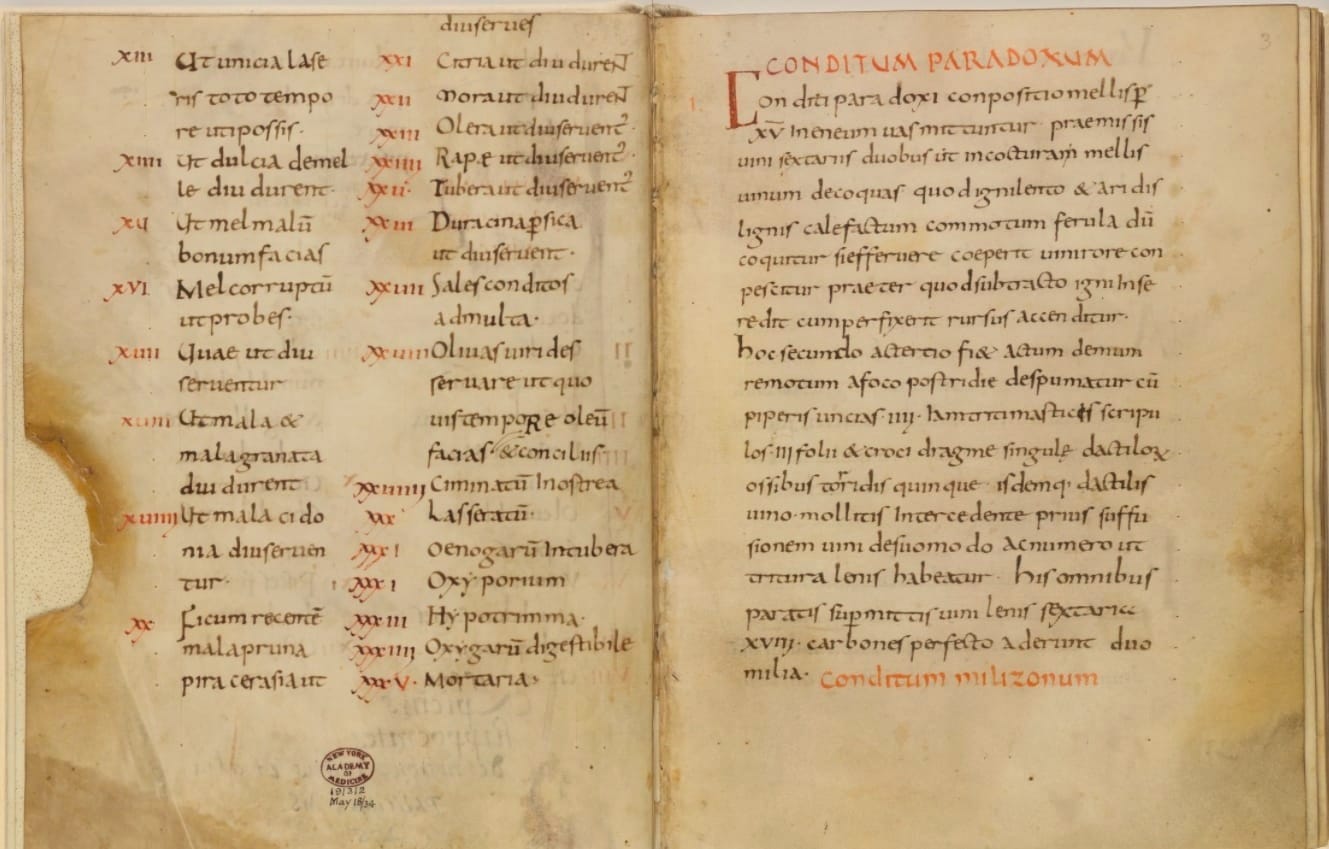

The surviving De Re Coquinaria, however, is not Apicius’ original work. It is a fourth-century CE compilation of over 500 recipes assembled by an unknown editor who attached Apicius’ name to lend authority and prestige. A further appendix of 52 recipes by Vinidarius was added in the fifth century. Despite its composite nature, the collection is the most complete ancient cookbook to survive.

Written in later Latin, the work is organised into ten books, each bearing a Greek title, including Epimeles (“The Careful Housekeeper”), Polyteles (“The Gourmet”), and Thalassa (“The Sea”). Its sources range from Apicius’ own writings to agricultural manuals, medical texts, and Greek and Roman dietary literature. The recipes combine the exotic and the everyday, from peacock dishes and stuffed dormice to herb dressings and digestive salts.

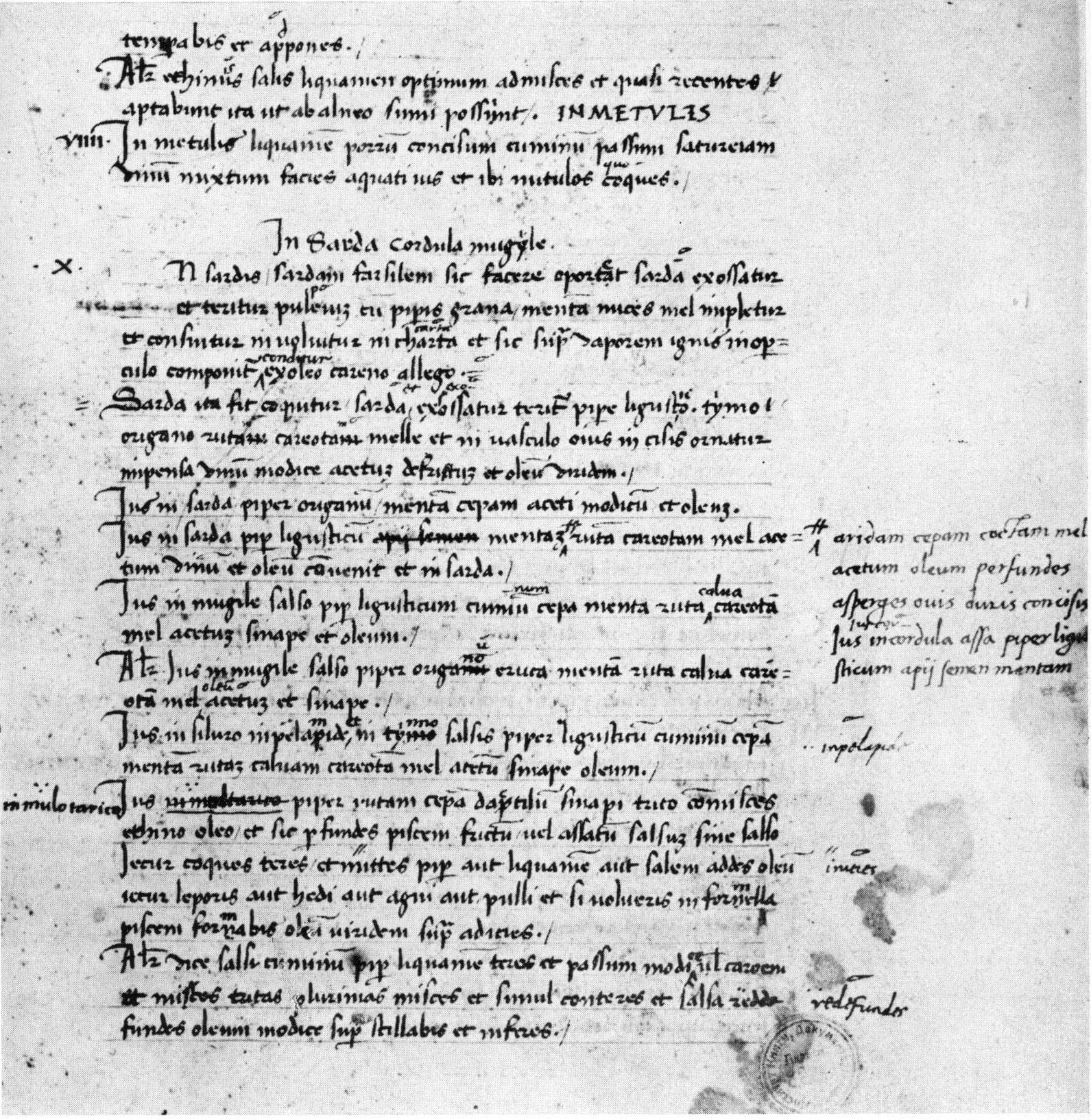

Book 10, devoted entirely to fish sauces, is often considered closest to Apicius’ original treatise. Seven recipes explicitly bear his name and show consistent seasoning preferences, including contrasts of hot meat with cold sauces. Many other recipes reflect elite taste for rare ingredients and imported spices.

The collection also reflects the empire-wide scope of Roman cuisine, with dishes described as Parthian, Alexandrian, Numidian, or Indian in style. Approximately sixty different condiments appear in the text, many familiar to modern cooks. Pepper, in particular, is ubiquitous, even appearing in dessert recipes. The demand for spices imposed heavy costs on the Roman state and shaped long-distance trade routes, especially after the discovery of the monsoon winds enabled direct sailing to India.

Apicius’ influence extended well beyond his lifetime. Later emperors, notably Elagabalus, explicitly imitated his extravagance, claiming to surpass him in novelty and excess (Augustan Histories, Elagabalus). Schools of cookery adopted him as a patron figure, and later writers used his name as a synonym for culinary excellence. His book circulated in medieval elite circles, was known at the court of Charlemagne, and continued to attract interest in the Renaissance and beyond.

Through De Re Coquinaria, Apicius remains central to our understanding of Roman food culture—not as a single authorial voice, but as the symbolic anchor for the richest surviving record of ancient cooking, taste, and gastronomic ambition. ("Cooks & other people". proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on food and cookery 1995. Edited by Harlan Wlaker)

A Name That Became a Warning

A dense web of stories surrounds the figure of Marcus Gavius Apicius, the most notorious gourmet of Roman antiquity. His reputation for greed is matched only by claims about his culinary expertise—though the precise nature of that expertise is far from clear. Contemporary writers such as Columella, Pliny, and Seneca speak with a unified voice, presenting Apicius as the ultimate embodiment of excess: a man consumed by food to the point of ridicule, a stylised figure of elite indulgence rather than a skilled practitioner of an art.

There is a strong narrative about his death. What gives this narrative its force is not poverty—Apicius was still wealthy—but the idea that he could not bear to eat ordinary food. The diet he rejected was not that of the destitute, dependent on coarse bread or thin porridge, but a respectable and balanced Mediterranean fare of vegetables, pulses, fish, and locally raised meat. The refusal of such food marks Apicius not as deprived, but as fundamentally alienated from moderation.

Luxury Without Labour

Before his reputation as a gourmet was fully formed, Apicius was already an extremely wealthy man with access to imperial circles. Seneca suggests that he even received financial support from the state, possibly to fund the kind of lavish hospitality expected of elite Romans entertaining foreign guests. His banquets were evidently remarkable, showcasing the most refined cuisine Rome could offer.

Yet despite this, the sources are silent on one crucial figure: the cook. Apicius himself is never described as preparing food. It is far more likely that his household employed exceptionally skilled chefs whose expertise rivalled that of any in the city. Whether their recipes were written down or preserved orally remains uncertain.

Doubts have often been raised about literacy among slaves and the urban poor, but such scepticism underestimates the prevalence of functional literacy. The language of the recipe collection associated with Apicius is plain, technical, and unadorned—precisely the kind of Latin that could be mastered with minimal formal education.

Roman elite attitudes toward culinary labour help explain why Apicius was never imagined as a cook. Cicero is explicit about which occupations were considered degrading:

“Now we have by and large been taught these points about which trades and occupations are to be thought decent and which ones are disgraceful: those trades are to be thought least proper which are the servants of physical pleasure: fishmongers, butchers, cooks, poultrymen, fishermen… add to these if you like perfume-sellers, dancers, and the whole entertainment industry.” Cicero

Such work was considered slavish, unworthy of a man of rank. Apicius therefore attracted criticism not because he laboured in the kitchen, but because he spent extravagantly on what others prepared. He was a consumer of luxury, not its producer. Nowhere do ancient sources describe him as a professional cook, nor as a freedman enriched through culinary skill. Although such figures existed, there is no evidence that Apicius belonged among them.

This distinction matters because it undermines the assumption that Apicius authored the recipe collection attributed to him. Scholars have long spoken cautiously of a text “attributed to Apicius,” yet rarely asked why that attribution arose. One hypothesis suggests that a later freedman cook adopted the name, but the text itself offers no authorial voice at all. There is no “I,” no framing, no claim of expertise. This silence strongly suggests that the work is not the product of a single author, but a compilation that developed organically, shaped by many hands over time.

How Cooks Disappeared and Recipes Survived

In Roman elite culture, knowledge of food was theoretical rather than practical. Physical labour was delegated to slaves; elite engagement with cuisine focused on sourcing, breeding, cultivation, and reputation. Agricultural manuals written by landowners contain detailed advice on farming and animal husbandry, but their authors never performed this work themselves. Recipes included in such texts were almost certainly gathered from household staff.

Medical and veterinary writers such as Galen and Vegetius also record remedies in recipe form, yet these too originated in the practices of freedmen and slaves. Greek specialists form an exception, as Greek culture placed greater value on practical skill, allowing artisans—including cooks—to write technical texts. Roman authors, by contrast, relied heavily on Greek knowledge in all technical fields.

This divide profoundly shaped Roman cookery. In Greek tradition, the mageiros combined theory and practice. Originally associated with sacrifice, by the fourth century BCE he appears in comedy as a free professional capable of organising an entire banquet. Dionysius captures the distinction:

“We are able to garnish, to carve, to cook sauces, and to blow on the fire, anyone can chance to do that; someone like that is only a food processor [opsopoios] but the master chef [mageiros] is quite different.”

In Rome, this division hardened. Practical cooking remained the work of enslaved opsopoioi, while culinary theory was appropriated by elite diners. As a result, food writing took two forms: elite texts with narrative and commentary, and anonymous recipe collections stripped of voice. The Apicius collection belongs firmly to the latter category.

Unlike works by Cato or Columella, which open with clear authorial intent, the Apicius collection speaks only through its instructions. Even the lost treatise by Apicius’ contemporary Gaius Matius apparently contained narrative discussion, reinforcing how unusual the silence of the recipe collection is.

The recipes themselves reflect professional kitchens. They are concise, technical, and practical, written in forms of Latin closer to everyday speech than literary style. The language smells of work rather than display. This diversity of vocabulary and grammar points to multiple authors and multiple periods. The collection cannot be the work of one man, elite or otherwise.

The name “Apicius” therefore functions less as authorship than as a label. By the second century CE it had become a byword for luxury. Juvenal jokes about poor men who aspire to Apician tastes. Later figures adopted the name as a cognomen to signal culinary ambition. Writers use “Apician” to denote fine food, excess, or greed, depending on context:

“that soul [of a glutton] will receive more pleasure… because it is interred in Apician and Lurconian spices.” Tertullian, De ieiunio

“Away with the seasoners of sauces, away with all the wiles of cooks, away with the dishes of Apicius.” Querolus

“There he will be treated with such comradeship as if up to this point he had belched among Apician feasters and Byzantine master carvers.” Sidonius Apollinaris

By this stage, “Apicius” no longer refers to a man but to a category of food and expertise. Tertullian even notes that cooks themselves were named after him:

“In the same way are not doctors named after Erasistratus, and grammar-teachers after Aristarchus, and cooks also after Apicius?”

The surviving manuscripts confirm this evolution. The collection circulated under the name Apicius without a formal title. De re coquinaria is a Renaissance invention. Variations in manuscripts, duplicate recipes, marginal additions, and linguistic inconsistency all point to gradual accumulation within professional cooking environments—possibly guilds such as the collegium cocorum Caesaris.

What survives, then, is not the voice of a reclining gourmet discoursing on sauces, but the residue of working kitchens. As a chef-text, it preserves technique rather than theory. Its anonymity is not a flaw but a clue.

The myth of Apicius endures because it satisfies expectations about Rome: excess, domination, appetite without restraint. Seneca condemns him accordingly:

“May the gods and goddesses ruin those whose greed crosses even the boundaries of our invidious empire!”

Yet stripped of myth, what remains is something rarer: a corpus shaped by enslaved and freed cooks, preserved under the borrowed authority of a famous name. The recipes of Apicius are not the work of Apicius. They belong to the cooks who made Rome eat. ("The Myth of Apicius" by Sally Grainger)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: