The Divine Chaos of Elagabalus: Rome’s Most Unconventional Emperor

A boy-emperor draped in silk and scandal, Elagabalus shook the Roman world with rituals, rumors, and rebellion. His brief reign remains one of the Empire’s most controversial and enigmatic chapters.

He came wrapped in silk, crowned by a god, and followed by scandal. Elagabalus ascended the Roman throne at just fourteen, not with a sword but with incense and sunfire, bringing with him the cult of a foreign god, a taste for theatrical ceremony, and a defiance of every Roman norm.

In a city built on discipline and tradition, he was excess incarnate—high priest and emperor, teenager and taboo. Reviled by ancient historians as a perverse tyrant and celebrated by some modern readers as a radical outsider, Elagabalus remains one of the most provocative enigmas of imperial Rome. His reign, though brief, ignited debates on power, identity, religion, and the price of difference—then and now.

A Boy Emperor’s Ascent

On the 16th of May, 218 CE, the Roman Empire shifted course in the dead of night. A fourteen-year-old boy named Varius Avitus Bassianus was smuggled into the camp of Legio III Gallica, stationed at Raphanaea in Syria.

The son of Julia Soaemias and a high priest of the local sun god Elagabal, he had gained attention for his striking appearance and ritual dancing. Now, draped in garments that had once belonged to the murdered Emperor Caracalla, he was proclaimed emperor by the troops at dawn.

The soldiers were told he was Caracalla’s illegitimate son—a rumor encouraged by his Severan relatives to restore dynastic legitimacy. Cassius Dio records the drama that unfolded:

“They carried Avitus, whom they were already styling Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, roundabout upon the ramparts, and exhibited some likenesses of Caracallus when [he was] a child as bearing some resemblance to the boy, at the same time declaring that the latter was truly Caracallus’ son, and the only rightful heir to the throne.

‘Why do you do this, fellow soldiers?’ they exclaimed. ‘Why do you thus fight against your benefactor’s son [τοῦ εῦεργέτου ὑμῳν υῐόν]?’

By this means they corrupted all the soldiers who were with Julianus, the more so as these were eager to revolt, so that the assailants slew their commanders, with the exception of Julianus, who escaped in flight, and surrendered themselves and their arms to the False Antoninus.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History, 79.32.2–3

Dio calls the new claimant "the False Antoninus" and insists the boy’s real father was Varius Marcellus, a Syrian aristocrat whose sarcophagus was later found in Velletri.

The Roman sarcophagus of Sextus Varius Marcellus, bearing a bilingual inscription in Greek and Latin, on top is the statue of a female nymph. Credits: Media Storehouse

Marcellus' wife, Julia Soaemias, was Caracalla’s cousin through Julia Domna—linking Elagabalus to the Severan house only by maternal blood. Still, the story worked. Whether the troops believed it or merely accepted it as a useful fiction, their loyalty to Caracalla’s memory and their dissatisfaction with Macrinus ensured the boy’s rise.

Macrinus, who had cut military wages and lacked dynastic credentials, had lost the army's affection. Elagabalus, on the other hand, revived Severan imagery and used the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus to forge continuity. Coins and inscriptions declared him divi Magni Antonini Pii filius, divi Severi Pii nepos—son of the divine Caracalla, grandson of the divine Severus. Veterans even traced his supposed ancestry to Nerva.

Visual propaganda played a central role. Early portraits of Elagabalus closely resembled those of Caracalla, particularly in hairstyle and facial features. Coins issued between 218 and 219 CE emphasized martial strength: Mars Victor, Victoria Augusti, Fides Militum, and Concordia Militvm all appeared as coin legends.

But the political landscape remained volatile. Dio notes that rebellion sprang up across the empire, inspired by the ease with which one could claim the throne:

"To such an extent, indeed, had everything got turned topsy-turvy that these men, one of whom had been enrolled in the senate from the ranks of the centurions and the other of whom was the son of a physician, took it into their heads to aim at the supreme power.

I have mentioned these men alone by name, not because they were the only ones that took leave of their senses, but because they belonged to the senate; for other attempts were made.

For example, the son of a centurion undertook to stir up that same Gallic legion; another, a worker in wool, tampered with the fourth legion, and a third, a private citizen, with the fleet stationed at Cyzicus, when the False Antoninus was wintering at Nicomedia; and there were many others elsewhere, as it was the simplest thing in the world for those who wished to rule to undertake a rebellion, being encouraged thereto by the fact that many men had entered upon the supreme rule contrary to expectation and to merit."

Cassius Dio, Roman History, 80.7.2–3

Elagabalus had reached the purple not by inheritance, achievement, or acclaim—but through a calculated performance staged by his family. The empire would soon learn what kind of performance he intended to give.

Although some of these attempts were more serious than others, the sheer number of challengers suggests that many individuals believed they had a chance at seizing imperial power. Declarations about the loyalty and unity of the legions were likely aspirational rather than factual—rhetorical efforts to promote an image of stability that did not reflect reality.

Once again, this underscores the fragility of Elagabalus’ reign. Having gained the throne through deception, the young emperor and his advisors actively distorted the political and military landscape to present him as a confident and commanding figure. In truth, his position was anything but secure.

God Above All: Elagabalus and the Sun that Ruled Rome

After securing the throne, Elagabalus remained in the East for the remainder of 218 CE, wintering in Nicomedia. It is likely that a sacred stone depicting the god Elagabal—the sun deity of Emesa, worshipped in the form of a conical black stone—traveled with him. Several Eastern coin issues depict this sacred stone in a quadriga, surrounded by military standards.

Herodian, writing as a contemporary, describes the emperor’s immediate devotion to his priestly role:

“Straight away (...) [he] began to practice his ecstatic rites and go through the ridiculous motions of the priestly office belonging to his local god in which he had been trained.”

Herodian, History of the Empire, 5.5.3

While performing these rites, Elagabalus allegedly wore lavish garments “woven of purple and gold,” adorned with necklaces, bangles, and a “crown in the shape of a tiara glittering with gold and precious stones.” According to Herodian”:

“The effect of this exotic attire was something between the sacred garb of the Phoenicians and the luxurious apparel of the Medes.”

Herodian, History of the Empire, 5.5.3–4

Elagabalus reportedly disdained Roman and Greek dress, dismissing their woolen garments in favor of Chinese silk. This portrayal by Herodian starkly contrasts with the imperial administration’s messaging, which tried to align the young ruler with Caracalla and Roman tradition. One story, possibly apocryphal, claims Elagabalus refused to wear a toga when entering Rome. Instead, he had a grand image prepared showing him sacrificing to Elagabal in his priestly robes.

This image was sent to the capital and hung in the senate house so that senators and citizens could become accustomed to his appearance ahead of his arrival. While the veracity of this tale is uncertain, a Roman antoninianus minted in 219 CE shows a strikingly similar scene: a figure—presumably the emperor—sacrificing at a small altar, with the god Elagabal in a quadriga behind him.

Whether true or not, what is clear is that Elagabalus sought to introduce his god to the Roman public. The deity was even titled CONSERVATOR AVGVSTI—“the emperor’s divine protector.”

But in 220 CE, the religious ambitions of Elagabalus intensified. He officially elevated Elagabal to the head of the Roman pantheon and adopted the title sacerdos amplissimus dei invicti Solis Elagabali—“most exalted priest of the invincible sun god Elagabal.”

Although he continued using the title pontifex maximus, inscriptions consistently placed his priestly identity first, signaling its supreme importance. New coin types followed suit, bearing images of Elagabalus in ornate priestly dress performing sacrifices, with inscriptions such as INVICTVS SACERDOS AVGVSTVS, SACERDOS DEI SOLIS ELAGABALI, and SVMMVS SACERDOS AVGVSTVS.

In his zeal, Elagabalus divorced his first wife, Julia Paula, and married Aquilia Severa, a Vestal Virgin. This likely served to merge his sun cult with the most sacred institution of Roman religion. Cassius Dio was scandalized:

“He plumed himself over an act for which he ought to have been scourged in the Forum, thrown into prison, and then put to death.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History, 80.9.4

Dio adds that Elagabalus even arranged a symbolic marriage between the god Elagabal and the Punic goddess Urania:

“As if the god had any need of marriage and children!”

Cassius Dio, Roman History, 80.12.1

Until his assassination in 222 CE, the cult of Elagabal held a central role in Roman religious life. A monumental temple was constructed on the Palatine Hill—not just on imperial property but at the symbolic heart of Rome. Herodian paints a vivid scene of Elagabalus’ ritual performances:

“Each day at dawn he [i.e. Elagabalus] came out and slaughtered a hecatomb of cattle and a large number of sheep which were placed upon the altars and loaded with every variety of spices.

In front of the altars many jars of the finest and oldest wines were poured out, so that streams of blood and wine flowed together.

Around the altars he and some Phoenician women danced to the sounds of many different instruments, circling the altars with cymbals and drums in their hands. The entire senate and the equestrian order stood round them in the order they sat in the theatre.

The entrails of the sacrificial victims and spices were carried in golden bowls, not on the heads of household servants or lower-class people, but by military prefects and important officials wearing long tunics in the Phoenician style down to their feet, with long sleeves and a single purple stripe in the middle.

They also wore linen shoes of the kind used by local oracle priests in Phoenicia. It was considered a great honour had been done to anyone given a part in the sacrifice.”

Herodian, History of the Empire, 5.5.8–10

Though Herodian’s descriptions may be exaggerated in terms of scale or frequency, the forced participation of senators and knights at these rites is consistent with the emperor’s attempt to restructure Roman religion around Elagabal.

Herodian also refers to a second Elagabal temple, possibly located in Trastevere. Once a year, at midsummer, the black stone of the god was ceremonially transported there from the Palatine. He describes the ritual procession:

“The god was set up in a chariot studded with gold and precious stones” and was “preceded by the emperor, holding the reins and walking backwards,” followed by a procession of standard bearers, sacred treasures, and images of other gods.

The cavalry and army were also compelled to join.

Herodian, History of the Empire, 5.6.6–8)

After the sacrifices, Elagabalus would mount a tall tower and toss lavish gifts into the crowd—gold and silver cups, garments, fine linen, even household animals. Through such dramatic gestures, he made sure that Elagabal, god of the rising sun, remained not only Rome’s new chief deity—but also its daily spectacle.

Priest Before Emperor: Elagabalus and the Failed Reinvention of Roman Religion

The radical religious policies of Elagabalus remain difficult to explain. Though he rose to power as the supposed son of Caracalla, the young emperor’s path diverged sharply from the model of a Roman princeps.

Rather than uphold Roman traditions with moderation and respect for Jupiter, he elevated a foreign deity—Elagabal—above the entire Roman pantheon. Personal devotion to a non-Roman god was tolerated, but displacing Jupiter was unprecedented.

One possible explanation lies in the emperor’s age. By the end of 220 CE, Elagabalus was no longer a fourteen-year-old puppet, but a maturing young man, likely starting to assert independence. It is plausible that he began to make decisions without direction from his handlers, possibly under the influence of Emesene priests who accompanied the black stone to Rome.

His devotion appears genuine. But this created a dilemma for the imperial administration: how could they persuade Rome—especially the Senate and the Praetorian Guard—to accept a high priest of a foreign god as emperor?

Coinage became a tool of persuasion. As aforementioned, Elagabal was presented as CONSERVATOR AVGVSTI—the emperor’s divine protector. This title was traditionally reserved for Jupiter but had occasionally been attributed to other gods. Using it for Elagabal aimed to frame the deity within a familiar Roman context.

Interestingly, Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum notes only two coin types from 220–222 CE showing the black stone, while at least twelve depict an anthropomorphic Sol. Two of these coins even label the god as CONSERVATOR AVGVSTI, possibly referring to Elagabal. Yet, none of the Sol-type coins bear the name Elagabal, leaving the figure’s identity ambiguous—perhaps deliberately so.

Most coins during this period featured Elagabalus sacrificing as high priest. While his garments were unlike the traditional toga, the overall imagery—the altar, the patera, and the act of libation—closely echoed that of the pontifex maximus.

Elagabalus is typically shown in trousers and a long-sleeved tunic, often with a chlamys, and wearing an imperial diadem rather than a tiara, despite Herodian’s claim that he wore:

“the most expensive types of clothes, woven of purple and gold, and adorned himself with necklaces and bangles,” completed by “a crown in the shape of a tiara glittering with gold and precious stones.”

Herodian, History of the Empire, 5.5.3–4

This modified outfit was likely a Roman reinterpretation of Syrian priestly dress—possibly even an innovation designed to appeal to the army. By the third century, Roman soldiers commonly wore trousers and long-sleeved tunics. Additionally, Cassius Dio notes that Caracalla wore similar “Germanic” clothing during his eastern campaigns. By mimicking this look, Elagabalus may have been invoking his father's memory to strengthen his own image.

Maybe his appearance as sacerdos amplissimus (most exalted priest) was a calculated appeal to military audiences, linking priestly authority with martial prowess. One coin inscription—INVICTVS SACERDOS AVGVSTVS, “invincible priest-emperor”—explicitly associates the emperor with the god’s power.

Although nicknames like Elagabalus and Heliogabalus imply divine embodiment, the emperor is never shown as Sol, and only wears a radiate crown on high-value coins. Still, his intimate connection to Elagabal may have implied a semi-divine status.

This identity—Elagabalus as mediator between mortals and the sun god—placed him in a unique role akin to that of pontifex maximus. Like the chief priest, the sacerdos amplissimus made sacrifices not for himself, but for all Romans, their peace and prosperity depending on the god’s favor. Only he could secure that favor.

Despite the administration’s best efforts, Elagabalus failed to gain acceptance. The cult of Elagabal appeared too foreign, its rituals too alien, and the emperor’s charisma too weak to overcome Roman suspicion. Later emperors like Constantine would claim divine favor through military victories and national reunification, but Elagabalus lacked such achievements. His legitimacy as a sacred ruler was never convincing.

In March 222 CE, the Praetorian Guard rebelled. Elagabalus, his mother, and many close associates were executed, their corpses mutilated, and their names erased by damnatio memoriae. Some interpret Elagabalus’s downfall as a cultural collision between the Roman West and Syrian East.

However, the regime did attempt to market the god using familiar Roman imagery and language. Whether Elagabalus himself cared for Roman norms remains uncertain, but his advisors certainly tried to bridge the cultural gap. They branded him as an invincible priest-emperor, hoping to harmonize innovation with tradition.

Ancient historians, however, offer no such nuance. Herodian portrays him as a caricatured Eastern despot, forcing alien rites upon an unwilling Rome. That depiction has endured. Instead of being remembered as a pious reformer or new Antoninus, Elagabalus is remembered as a theatrical tyrant—a tragic case of a ruler whose religious vision was rejected not only by Rome, but by history itself. (From Priest to Emperor to Priest-Emperor: The Failed Legitimation of Elagabalus, by Martijn Icks)

From Slandered Teen Emperor to Symbolic Enigma

No definitive synthesis exists that successfully integrates Elagabalus’s political, economic, and religious initiatives into a unified historical portrait. Most authors have focused on what happened and why—but equally revealing are the layers of image-making that followed.

From propaganda issued by the imperial court, to damning character sketches penned by Roman historians, from scholarly works to artistic and literary reimaginings, the emperor’s posthumous identity has been rewritten countless times. Like Commodus portrayed as Hercules or Nero as a pyromaniac monster, Elagabalus became a caricature.

Ancient sources condemned him, while later generations turned him into a symbol—a pagan, a mad tyrant, or a queer martyr, depending on the era and agenda. The imperial propaganda of his reign, the hostile narratives of antiquity, and the many reinterpretations in art, fiction, and scholarship all orbit around the same elusive figure: a teenage high priest who ruled Rome from 218 to 222 CE.

Why did such a short and obscure reign inspire so many vivid and conflicting portrayals? What aspects of Elagabalus’s character were exaggerated, erased, or reimagined—and why?

Who Pulled the Strings?

Although Elagabalus ascended to the imperial throne in 218 CE, he was only fourteen years old at the time—far too young to independently govern the Roman Empire. Most ancient and modern accounts agree that he was primarily a puppet for others, particularly his politically astute Syrian family.

Chief among them was his grandmother Julia Maesa, the mastermind behind his rise, and his mother Julia Soaemias, both of whom wielded considerable influence during his reign. Inscriptions honor them with exalted titles such as Augusta, mater castrorum et senatus, and mater Augusti, suggesting not just familial reverence but real political agency.

However, Elagabalus's regime did not solely rest in the hands of these powerful women. Figures such as P. Valerius Comazon, a former commander of Legio II Parthica, rose quickly through the ranks, becoming praetorian prefect, consul, and city prefect.

Another official, whose name is partially lost in the sources but who held titles such as comes and amicus fidissimus, also climbed to the top of the imperial administration. Their careers, deeply rooted in military service, hint at the strong sway the army may have held—at least early on. Surprisingly, once Elagabalus was settled in Rome, there’s little evidence that military affairs continued to dominate. No wars were fought, and the army faded from coin imagery.

Instead, continuity was observed in the senatorial elite: many men who served under Caracalla and Septimius Severus retained their positions under Elagabalus and were carried into the next reign under Severus Alexander. It’s likely that these senators, loyal to the Severan legacy, were integral in stabilizing the administration behind the scenes.

Despite accusations by ancient authors that Elagabalus appointed unqualified favorites—chariot drivers, dancers, and actors—to important positions, there is scant material evidence to support this. Figures like Hierocles and Aurelius Zoticus, frequently mentioned in literary sources as scandalous appointees, do not appear in inscriptions. While Elagabalus rewarded allies like Comazon with high office, this was not an unusual practice. Even controversial equestrian appointments to senatorial provinces had precedents in earlier reigns.

Financially, the emperor continued Caracalla’s debasement of the denarius but maintained stable gold coinage. The four known congiaria (public gifts) during his short reign represent an unusually high frequency, possibly contributing to fiscal strain.

Although the Historia Augusta accuses him of excessive building and spending, archaeological evidence shows that his main constructions included a circus and temples dedicated to the god Elagabal, as well as modest repairs to public infrastructure. In sum, the charges of mismanagement and nepotism made by ancient authors seem more rooted in moral disapproval than fact.

The reign of Elagabalus was less a circus of chaos than a continuation—albeit with interruptions—of Severan governance. What truly undermined him was not incompetence, but his failure to satisfy the expectations of Rome’s traditional elite. As a teenage priest-king representing a foreign deity and flanked by powerful women, Elagabalus embodied a model of imperial rule that was too radical for the Roman establishment to accept. His administration may have tried to cloak its novelty in familiar iconography, but the mask did not convince.

The Final Curtain

By 222 CE, Elagabalus had alienated the imperial elite and the praetorian guard through his foreign religious reforms, erratic behavior, and unpopular court appointments. When he adopted his cousin Alexander as Caesar, the young heir became a rallying point for those seeking a more traditional, Roman image of power.

Despite efforts to reverse his unpopularity, Elagabalus’s authority crumbled. In a final act of desperation, he tried to eliminate Alexander—but the praetorians turned on him. On March 13, Elagabalus and his mother Julia Soaemias were murdered, their corpses dragged through the streets and dumped in the Tiber. His reign, and his god’s moment in the Roman sun, were obliterated by a damnatio memoriae.

The religious policies of Elagabalus—foreign in appearance and uncompromising in implementation—were too radical for Rome's conservative elite. Even more dangerous, they alienated the praetorian guard, whose favor was essential for any emperor’s survival.

Ancient sources like Cassius Dio, Herodian, and the Historia Augusta all attribute the young ruler’s downfall to his perceived immorality and misplaced favoritism, particularly toward his lover Hierocles.

The image of a gender-defying priest-emperor in silk and gold, worshipping a conical black stone and elevating actors and charioteers to positions of power, was simply too much for the traditional order to bear.

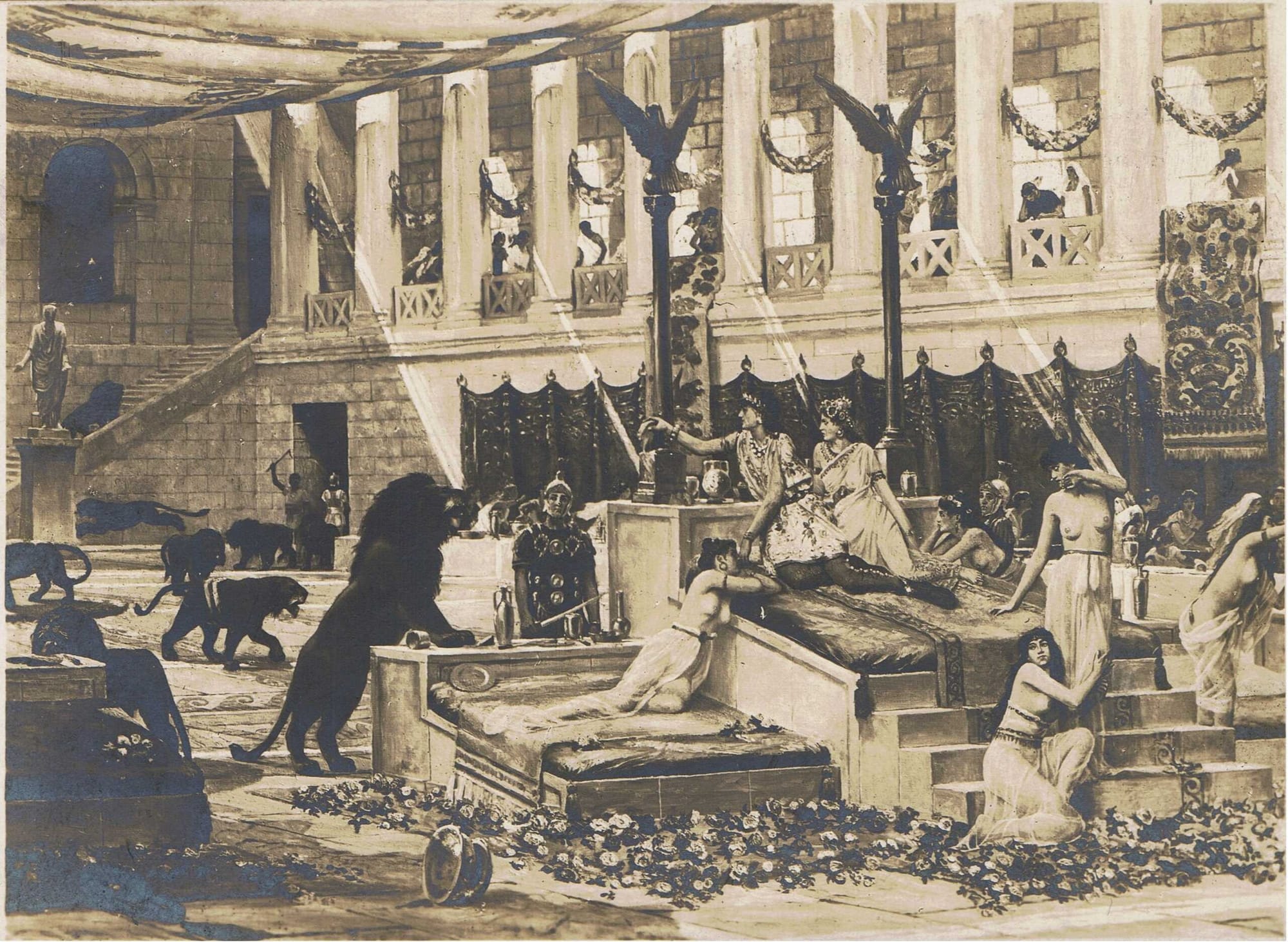

Wall painting in the inner courtyard of Castle Forchtenstein in Austria, showing Roman emperor Elagabalus. Public domain

Sensing disaster, Julia Maesa orchestrated a strategic pivot. She persuaded Elagabalus to adopt her other grandson, Alexianus, as Caesar in the summer of 221 CE. The boy, renamed Marcus Aurelius Alexander, was styled as Elagabalus’s heir, but he was deliberately distanced from the emperor’s religious agenda.

Coins bearing Alexander’s image emphasized pietas and traditional Roman rituals—patera, lituus, and simpulum—while Elagabalus continued to appear in “Oriental” dress sacrificing to Elagabal. If harmony ever existed between them, it was brief. Elagabalus, feeling increasingly threatened, attempted to murder Alexander, but the praetorian guard protected the young Caesar.

Herodian writes that when the emperor tried to involve Alexander in his priestly rituals, his mother Mammaea intervened:

“She removed him from contact with such activities which were shameful and unbecoming for emperors… and gave him both a Latin and a Greek education.”

Herodian, History of the Empire, 5.7.1

The rift deepened. Elagabalus divorced Annia Faustina—whose ancestry linked her to Marcus Aurelius—and remarried the controversial Vestal Aquilia Severa. This move likely worsened tensions with the Roman elite.

Meanwhile, his repeated attempts to sideline Alexander only bolstered the boy’s popularity. According to Dio, Elagabalus complained that “he could not satisfy the praetorians, regardless how much he gave them.” Eventually, the emperor's desperation led him to the praetorian camp in person.

According to Dio, this was a fatal mistake:

“He made an attempt to flee, and would have got away somewhere by being placed in a chest, had he not been discovered and slain, at the age of eighteen. His mother, who embraced him and clung tightly to him, perished with him; their heads were cut off… his [body] was thrown into the river.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History, 80.20

Herodian’s account confirms the soldiers’ outrage. When Elagabalus spread a rumor that Alexander was dying, the guard demanded to see the boy. Once Alexander appeared unharmed, Elagabalus lost all credibility.

Herodian recounts how the soldiers turned on the emperor, his mother, and his followers, dragged their bodies through the city, and cast them into the sewer.

“Since the sewer turned out to be too small to dump his corpse, it was finally plunged from the Aemilian Bridge into the Tiber, with a weight attached to it to make sure it would sink.”

Suetonius, Historia Augusta, Vita Heliogabali 17.3

On March 14, 222 CE, the senate officially recognized Alexander as emperor. The damnatio memoriae against Elagabalus was swift and thorough: names erased from inscriptions, honors revoked, and his memory blotted from official records. Alexander, now styled as the son of Caracalla, wiped away all reference to his predecessor.

Even Elagabal, the god who had stood above Jupiter, was removed. His sacred stone was not destroyed but returned to Emesa. The temple on the Palatine was rededicated—likely to Jupiter Ultor, the Avenger. Rome’s divine order, had been restored. (The Crimes of Elagabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome’s Decadent Boy Emperor, by Martijn Icks)

Elagabalus’s downfall was not simply the collapse of a reign—it was the rejection of a vision. The Roman world could tolerate strangeness, ambition, even youth—but not a priest-emperor who danced to a foreign rhythm, loved without shame, and dared to reorder the divine hierarchy. He ruled for less than four years. In death, he was denied burial, stripped of memory, and written into history as Rome’s cautionary tale.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: