The Defeat Rome Never Forgot: Teutoburg Forest, 9 CE

In 9 CE, Roman authority in northern Europe collapsed in a landscape it believed already secured. The destruction of three legions in Germania did more than shock contemporaries – it reshaped Rome’s frontiers, ambitions, and memory of empire itself.

In the late summer of 9 CE, Roman authority in the north appeared secure. The frontier along the Rhine was heavily garrisoned, alliances had been negotiated, and the language of administration—courts, censuses, taxation—was already being spoken deep beyond the river. To contemporaries in Rome, Germania no longer looked like an active war zone, but a region in the process of becoming orderly, legible, and obedient.

What followed, however, would expose how fragile that confidence was. Somewhere in the wooded interior of the north, Roman power encountered a form of resistance it did not understand—and the consequences would echo through imperial memory for generations.

The Clades Lolliana and Rome’s Sense of Humiliation

Toward the end of the summer of 17 BC, a coalition of Germanic tribes – the Sugambri, Usipetes, and Tencteri – crossed the Rhine, raided into Gaul, and crucified Roman citizens. Such frontier violence was not unusual, but the incident escalated when the raiders ambushed a Roman cavalry detachment and surprised Marcus Lollius, the senior Roman commander in Gaul. The encounter ended with the capture of a legionary standard, the eagle of Legion V Alaudae.

The loss of an eagle carried symbolic weight far beyond the military reality. Although the tribes quickly withdrew and offered hostages, the episode entered Roman memory as the clades Lolliana. Later writers inflated it into a disaster comparable to Varus’ defeat, transforming a minor frontier reverse into a moral and political affront. As Suetonius later insisted – implausibly – Augustus was portrayed as a ruler who

“never invaded any country nor sought to extend the empire’s boundaries”,

a claim that sat uneasily with events on the Rhine.

Poetry amplified the sense of outrage. Crinagoras celebrated the recovery of the eagle in language that elevated humiliation into heroic sacrifice, while later historians retrospectively framed the incident as a turning point. In reality, it provided Rome with something more useful than a military lesson – a justification.

Germany Before Germania: Rome’s First Encounters Beyond the Rhine

Roman awareness of the peoples beyond the Rhine long predated Augustus. Julius Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul brought the Germans into written history, and his assessments sharply distinguished them from the Gauls. They were poorer, harder, and more warlike. Caesar noted that the Gauls no longer dared compare themselves to German bravery and regarded German life as simpler and more austere.

His two crossings of the Rhine in 55 and 53 BC were brief and punitive, intended less to conquer than to intimidate. Their practical effect was limited, but symbolically they mattered enormously. They demonstrated that the Rhine was not an absolute barrier and that Roman arms could reach even the edge of the known world.

After Caesar’s assassination, his reputation lingered in Germania. His sword was reportedly preserved in Cologne, a mark of respect that did not translate into submission. Gaul was broken after Alesia; Germany was not.

From Intimidation to Ambition: The Hardening of Roman Policy

Under Augustus, Germany ceased to be merely an extension of Gallic security policy. Although no fixed northern frontier can be credited to long-term planning, Roman strategy hardened into expansion. What began as intimidation evolved into conquest, and conquest gave way to an attempt at administration.

Roman confidence grew steadily. Propertius could celebrate the

“enslavement of the marsh-dwelling Sugambri”,

while Horace asked who could fear Parthians or Germans while Caesar lived. The assumption was not whether Germany would be subdued, but when.

The Rhine as Frontier: Camps, Commerce, and Control

Augustan policy combined force with relocation and trade. Loyal tribes such as the Ubii were resettled west of the Rhine, forming buffer communities that shielded Gaul. Their move laid the foundations for Cologne, which developed into an urban and commercial centre.

Trade followed soldiers. Roman merchants penetrated deep into German territory, supplying wine, metal goods, and prestige items. Linguistic traces survive: the German verb kaufen derives from the Latin caupo, “wine merchant”. Archaeology confirms long-distance exchange reaching as far as the Baltic.

Yet stability was fragile. Rebellions flared repeatedly, and Roman authority east of the Rhine remained provisional. The frontier was porous, reactive, and vulnerable.

Drusus Takes Command: Exploration, Engineering, and War

In 13 BC Augustus entrusted the German command to his stepson Drusus. Young, popular, and politically reliable, he embodied the new generation of imperial leadership. His early campaigns focused on reconnaissance and infrastructure as much as combat.

Naval expeditions traced the North Sea coast, while canals – notably the Fossa Drusiana – connected the Rhine to northern river systems, opening routes to the Ems, Weser, and Elbe. These works transformed logistics and allowed Roman forces to strike deep into Germania with unprecedented speed.

Drusus’ advances were hard-fought. Campaigns along the Lippe and toward the Weser exposed the army to ambush and attritional warfare. Cassius Dio records moments when Roman forces were trapped in narrow passes and narrowly avoided destruction.

Semi-permanent camps such as Oberaden reveal both ambition and insecurity. Towers, heavy defences, and vast supply stores point to a long-term presence, yet also to constant fear. Even so, Roman logistics delivered Mediterranean foodstuffs – and even Indian pepper – to soldiers deep in Germany.

Death on the Frontier and the Making of a Roman Hero

In 9 BC, after reaching the Elbe, Drusus’ campaign halted. Ancient sources speak of a prophetic apparition warning him to turn back; modern scholars suggest mutiny and exhaustion. Shortly afterward, a riding accident left him mortally injured.

Tiberius raced across the empire to his brother’s side. Ancient writers turned the journey into a moral exemplum of fraternal devotion. Drusus died shortly after, his body returned to Rome and interred in Augustus’ mausoleum. He was posthumously granted the title Germanicus.

Poetry and monuments transformed him into a martyr of expansion. Yet his achievements were limited: Germany was probed, mapped, and intimidated – not conquered.

Withdrawal Without Defeat: Tiberius and Strategic Recalibration

Tiberius inherited an unstable frontier. Camps such as Oberaden were abandoned and deliberately destroyed, not in panic but as part of a controlled withdrawal. Roman policy shifted from bold advance to consolidation.

For nearly a decade, sources fall silent. Commanders changed, rebellions continued, and Roman control remained shallow. The illusion of pacification persisted, sustained by triumphs and rhetoric rather than facts on the ground.

The Illusion of Pacification

By AD 6, Rome believed Germania secure enough to attempt a major campaign against Maroboduus, whose powerful confederation threatened the Danube frontier. Plans collapsed when a massive revolt erupted in Illyria, forcing Rome to divert troops on an unprecedented scale.

The shock exposed the fragility of imperial control. Augustus required a steady administrator in Germany – someone who could govern, tax, and pacify without provoking revolt.

The choice fell on Publius Quinctilius Varus.

A Reputation Forged After Defeat

Publius Quinctilius Varus has long been remembered as an inept and unsuitable governor, an image shaped largely by hostile ancient commentators and reinforced by modern caricature. Contemporary authors describe him as cruel, naive, or sluggish, with Velleius Paterculus offering the most damaging portrait:

“A man of mild character and quiet disposition, somewhat slow in mind as he was in body.”

Yet this judgement reflects post-disaster scapegoating rather than Varus’ actual standing before AD 9. It is implausible that Augustus would have entrusted the Rhine armies to an incompetent at a moment of instability. Until Teutoburg, Varus’ career had been consistently successful.

Born in the late 40s BC into a long-established patrician family, Varus belonged to Rome’s governing class by pedigree rather than celebrity. His father, Sextus Quinctilius Varus, had backed the losing side in the civil wars and committed suicide after Philippi, but this did not impede his son’s advancement under the Augustan regime.

Varus followed a conventional but notably accelerated cursus honorum. By 22 BC he had been selected as quaestor to accompany Augustus on an extended eastern tour, a rare mark of imperial confidence. In Asia he gained direct experience in taxation, civic administration, and provincial governance—skills that would define his later career.

His advancement continued. In 13 BC he reached the consulship alongside his brother-in-law Tiberius, firmly aligning his fortunes with the imperial household. His political standing at this moment is reflected in his association with the dedication of the Ara Pacis, where he likely appeared among the senior figures of the Augustan elite.

Marriage further consolidated his position. His second wife, Vipsania, was a daughter of Marcus Agrippa, binding Varus directly into the imperial family, while other familial alliances tied him to influential senatorial houses. These connections placed him securely within Augustus’ inner circle.

Governor of Africa: Securing Rome’s Granary

Varus’ first major provincial command came in Africa (8–7 BC), one of Rome’s most sensitive regions due to its role as a primary grain supplier. Although formally a senatorial province, Africa still housed a legion, requiring both political tact and military oversight.

Varus maintained stability, ensured uninterrupted grain shipments, and avoided serious unrest—an achievement that confirmed his reliability in a post where failure carried empire-wide consequences.

Governor of Syria: Authority at the Empire’s Edge

In 6 BC Varus was appointed governor of Syria, among the most demanding commands in the empire. He oversaw four legions, volatile client kingdoms, and the Parthian frontier, operating at great distance from Rome with substantial autonomy.

His tenure was dominated by events in Judaea following the death of Herod the Great. Varus attempted mediation in the succession crisis and responded decisively when unrest erupted. According to Josephus, revolt was suppressed swiftly and harshly, culminating in mass crucifixions but restoring order without prolonged instability.

From Rome’s perspective, Varus had acted efficiently and within expectations. He left Syria with his reputation intact.

Appointment to Germany

By AD 6–7, Varus was appointed to command in Germany, entrusted with five legions and extensive auxiliary forces. Whether Germany was formally a province or a territory in transition mattered less than the authority he exercised there, which was effectively absolute.

His remit was administrative as well as military: security, taxation, legal adjudication, and cooperation with local elites. Ancient critics later portrayed these measures as naive or provocative, but they were standard instruments of Roman consolidation.

Archaeology now confirms that Roman civilian and administrative presence east of the Rhine was more advanced than once assumed. Sites such as Waldgirmes and Haltern show forums, workshops, water systems, and mixed Roman–German populations. Cassius Dio’s claim that Germans were adapting to Roman civic life is no longer dismissed as rhetorical exaggeration.

Varus was overseeing a transition already underway—from conquest to direct rule.

The Man Before the Disaster

Before Teutoburg, Varus embodied the qualities Cicero once said defined a great commander:

“Military experience, bravery, prestige, and luck.”

He had governed Africa and Syria successfully, managed rebellion, administered complex provinces, and maintained imperial confidence. Far from being an obvious failure, Varus was regarded as a safe and capable choice for Germany — a governor trusted precisely because the region seemed already secured.

What followed in September AD 9 would redefine his reputation entirely.

Arminius: Roman Officer Turned Enemy

To Rome, Arminius was not only a rebel but a mutinous Roman-trained officer. A Cheruscan noble born around 18 BC, he served as an auxiliary commander, earned Roman citizenship and equestrian rank, and mastered Latin. Tacitus credits him with unusual intelligence and courage. That background mattered more than any myth – he learned Rome well enough to fight it.

The Cherusci and Their Society

The Cherusci lived between the Weser and the Elbe (roughly Lower Saxony). Roman writers mocked Germania as wild and unproductive, yet archaeology and environmental evidence point to a settled, agrarian landscape with cereal farming, livestock, ironworking, and surplus storage. This was a functioning countryside, not an empty wilderness.

Rome advanced through elite management as much as force – rewarding chiefs, promoting cooperation, encouraging towns, markets, courts, and cult sites. Tacitus frames the process with irony:

“They called it civilisation, when it was but a part of their slavery.”

Gifts, subsidies, and trade drew elites into dependency. Roman silver circulated widely beyond the frontier, helping shift exchange away from pure barter.

Cheruscan politics were fractured. Arminius led the anti-Roman faction; Segestes remained pro-Roman; Inguiomerus shifted with events. The survival of strong pro-Roman support shows AD 9 was not a unified national revolt but a coalition held together by success and fear.

Cassius Dio gives two drivers: Germans were treated

“as if… slaves”,

and Varus imposed taxation,

“exacting money as he would from subject nations.”

The move from allied partner to near-province brought taxes, courts, and a permanent army presence. For elites, this meant loss of autonomy and rising financial pressure – practical grievances, not abstract slogans.

Germanic warfare favoured speed, light weapons, and terrain. Tacitus describes spears and javelins as dominant; “naked” likely meant without armour. Arminius did not copy Roman methods – he used Roman knowledge (routine, confidence, logistics) against them, shaping conditions where Roman strengths became liabilities.

AD 9 may reflect a moment when taxation and control felt irreversible, and when Arminius had consolidated enough support. His goal was not “Germany” as a nation – Tacitus’ “liberator of Germany” is hindsight – but more plausibly preventing a Roman province east of the Rhine. Cassius Dio notes Arminius stayed close to Varus, “often shared his mess,” while preparing the betrayal that would follow.

A Province That Looked Quiet

By late summer AD 9, Quinctilius Varus appears to have treated Germany as a province in the making rather than a frontier still in flux. The season had been dominated by administration – diplomacy, local dispute-handling, routine patrols – the kind of work that signals a region is being normalised.

Into that atmosphere came Segestes’ warning: Arminius, the Cheruscan leader who had served Rome, was plotting revolt. Varus dismissed the report, reading it as exaggeration or as a move in tribal politics rather than the early signal of a coordinated strike. The failure was not ignorance – it was interpretation.

Arminius was able to act precisely because he was trusted. He had spent the summer close to Varus and moved within the Roman camp as an ally. When he and his auxiliaries rode off under the pretext of gathering support and reconnaissance, the Romans accepted it as procedure – and handed their advance intelligence to the man organising the ambush.

The force marched as if through cooperative territory. Its length, its baggage, and the presence of camp followers made it an impressive machine of movement but a poor instrument for sudden combat. Once weather and difficult ground slowed progress, order became dislocation – and dislocation made the army vulnerable to repeated blows.

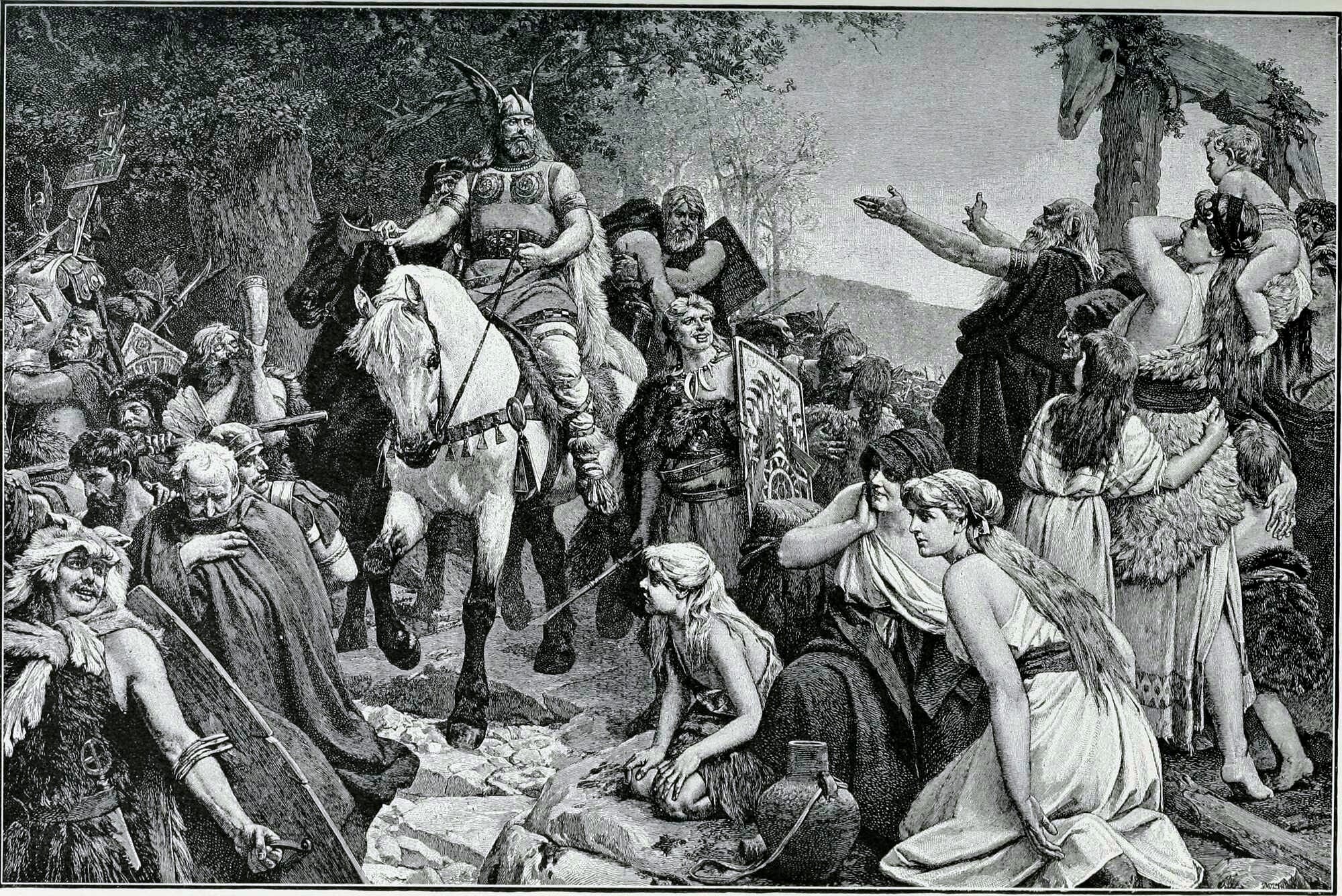

Kalkriese – Where Movement Becomes Confinement

Later sources disagree on details of route and sequence, but a consistent logic emerges: the Romans were pressured into terrain that restricted their ability to regroup. Near Kalkriese, a narrow corridor between higher ground and wet lowland offered attackers what they needed – confinement, surprise, and the ability to strike against separated elements of the column.

Archaeological traces of ramparts along the corridor add force to the picture, suggesting the space was shaped to narrow movement and channel troops into the most difficult ground.

In those conditions, Roman advantages were blunted. Formations were hard to assemble; cavalry became difficult to use; fighting turned into exhaustion and confusion under sustained attack. The end was not a single decisive clash but a breaking of cohesion. Wounded and surrounded, Varus chose suicide rather than capture, and the remaining resistance unravelled.

The result was catastrophic – the legions were destroyed and the standards taken. Roman positions east of the Rhine were abandoned or overwhelmed, and the political meaning was immediate: Germany could not be treated as a settled province. Later tradition preserves the story of a lone stronghold holding out long enough to contain the shock, a final reminder that after Teutoburg, Rome’s priority was no longer expansion, but survival and boundary.

Rediscovering the Battlefield

For centuries, the location of Rome’s greatest defeat remained uncertain. Ancient authors gave no precise coordinates, and northern Germany offered countless plausible landscapes. By the nineteenth century, more than six hundred proposed sites had been put forward, ranging from cautious reconstructions to pure speculation.

A decisive suggestion was made by Theodor Mommsen, who noted the concentration of Augustan coins found near Kalkriese, at the edge of the Great Moor below the Wiehen Hills. The topography matched the ancient descriptions: a narrow corridor between high ground and marsh, ideally suited to ambush. Lacking physical evidence of combat, however, Mommsen’s conclusion was largely dismissed.

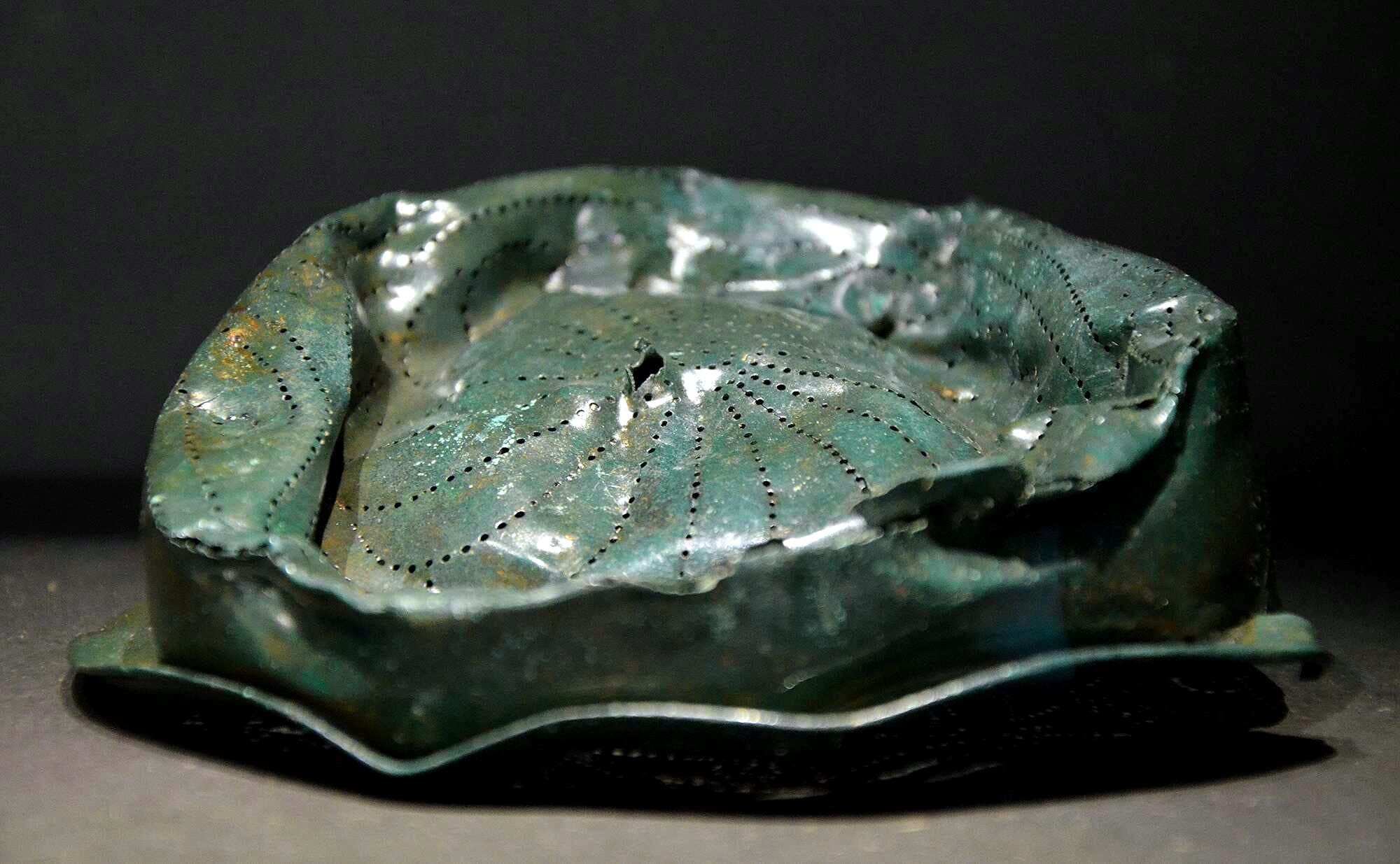

Confirmation came only in 1987, when Tony Clunn, a British army officer and metal-detector enthusiast, uncovered Roman silver denarii along an ancient roadway at Kalkriese. What initially appeared to be a dispersed hoard soon proved otherwise. The discovery of Roman sling bullets in 1988 established the site as military rather than commercial, prompting systematic excavation.

Archaeology provided cumulative proof rather than a single decisive find. Thousands of artefacts—weapon fragments, armour fittings, coins, medical instruments, and personal items—were recovered across a wide area, consistent with a prolonged, mobile engagement rather than a single pitched battle. Almost all finds were Roman, reflecting ancient accounts that the victors stripped the dead. The absence of Germanic equipment reinforced this pattern.

The numismatic evidence proved crucial. All coins recovered date to the reign of Augustus, with none later than AD 1. Many were countermarked, a practice associated with military pay, and among these appeared stamps reading VAR, used only during the governorship of Publius Quinctilius Varus. No other known conflict in his tenure could account for material on this scale.

Together, terrain, artefact distribution, and coinage establish Kalkriese as a principal battlefield of the Varian disaster. While the fighting extended over many kilometres, this narrow pass marks the point where Roman movement collapsed into confinement—and where defeat became irreversible. (“Rome’s greatest defeat. Masacre in the Teutoborg Forest” by Adrian Murdoch)

The defeat in the Teutoburg Forest did not merely destroy three legions; it forced Rome to recognise the limits of its power. Expansion halted, ambition recalibrated, and the Rhine hardened into a permanent frontier. Germania was no longer a province in waiting but a boundary never again seriously crossed. Long after the bones were buried and the standards lost, the lesson endured: Rome could dominate much of the known world, but it could not master every landscape, nor every form of resistance.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: