Stoic in the Sauna: Why a Baiae Bathhouse Linked to Cicero is Deliciously Ironic

A newly discovered sunken bathhouse at Baiae may have belonged to Cicero. For Rome’s sternest moralist, the irony is sharp: the prophet of virtue and temperance relaxing in the Empire’s most notorious playground.

The Bay of Naples is a place where the ground itself has never stood still. Volcanic activity has made whole cities rise and sink in slow motion, and none more dramatically than Baiae.

Baiae Rises from the Waves

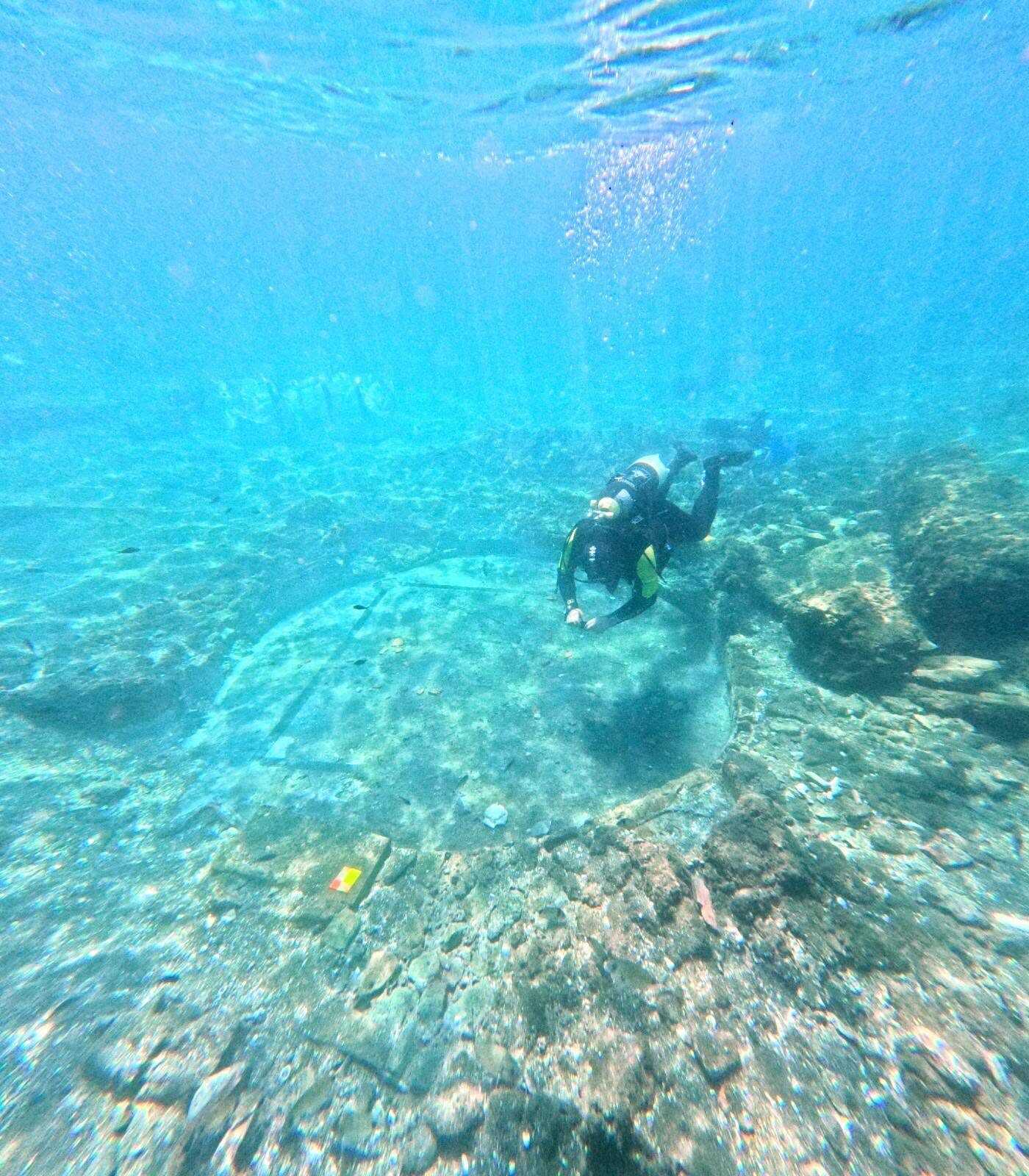

Bradyseism — the gradual up-and-down breathing of the earth — eventually drowned vast swathes of its marble villas and colonnaded streets beneath the Tyrrhenian Sea. Divers now swim through what was once the Republic’s most notorious resort town, where gilded mosaics and soaring arches are reduced to fish-haunted ruins.

The latest discovery, announced by Italian archaeologists in mid-August 2025, is a hypocaust-heated chamber — a laconicum, or dry sweating room — with traces of mosaic still intact and the suspended pillars of the heating floor standing like a miniature forest beneath the waves. The chamber belonged to a villa complex associated in ancient sources with Cicero, who is known to have owned property at Baiae. Suddenly, one of Rome’s loudest moralists has been swept into the story of the Empire’s “sin city.”

BBC’s article on Baiae and their vivid description as a sinful city of the Empire

Rome’s Playground of Vice

If Capri was a jewel and Pompeii a trading hub, Baiae was something else: a pleasure capital. Hot springs bubbled naturally from volcanic fissures, feeding a sprawl of terraced pools. Villas poured down the hillside toward the water, each with its own harbor, banqueting halls, and panoramic dining spaces that opened onto the bay. Julius Caesar kept a retreat here. So did Lucullus, the gourmet whose name became a byword for luxury. Later, Caligula built a floating bridge across the harbor to parade his power, and Nero ordered lavish feasts here that made the place infamous.

Ancient writers were scathing. Propertius warned that Baiae was “fatal to chaste girls” (Elegies 1.11), a shoreline where fidelity dissolved as quickly as salt in water. Seneca sneered in his Moral Letters (51.11):

“I left Baiae because the place was a show of vice… luxury is never far from disgrace.”

For Juvenal, it was a shorthand for excess, a place where fortunes were squandered on baths and banquets rather than virtue and civic duty (Satires 4.141). Even Martial, who enjoyed witty indulgence, called Baiae “a harbor of vice.”

To imagine Cicero’s name attached to this town is to set irony in stone. Cicero, the man who wrote page after page on temperance, moderation, and the moral duties of the citizen, soaking in a sweating chamber in the very place his peers condemned as Rome’s gilded cesspit.

Cicero’s Moral Universe

Cicero’s texts are saturated with the language of duty and virtue. In De Officiis (1.22), written for his son, he declared:

“We are not born for ourselves alone. Our country, our friends, have a share in us.”

Here was a vision of Roman life as an interlocking web of obligations — not to indulgence but to justice, courage, temperance, and wisdom. In the Tusculan Disputations (5.18), he dismissed pleasure as fleeting:

“What is sweeter than virtue itself? What is stronger, what more lasting? All other pleasures vanish, but virtue alone stands firm.”

Again and again, he framed true happiness as rooted not in luxury but in decorum — the fitting behavior of a Roman citizen who balanced public service with self-control. Even when Cicero tempered his Stoicism with Academic skepticism, the message was the same: virtue comes first. In De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum (2.35), he insisted:

“We are called away from pleasure by the dignity of virtue.”

This was the man who despised the moral collapse he saw in figures like Catiline, who linked luxury and political corruption in fiery speeches from the rostra. That such a voice should echo from a sweating chamber at Baiae is what makes this archaeological find more than just another mosaic under the sea.

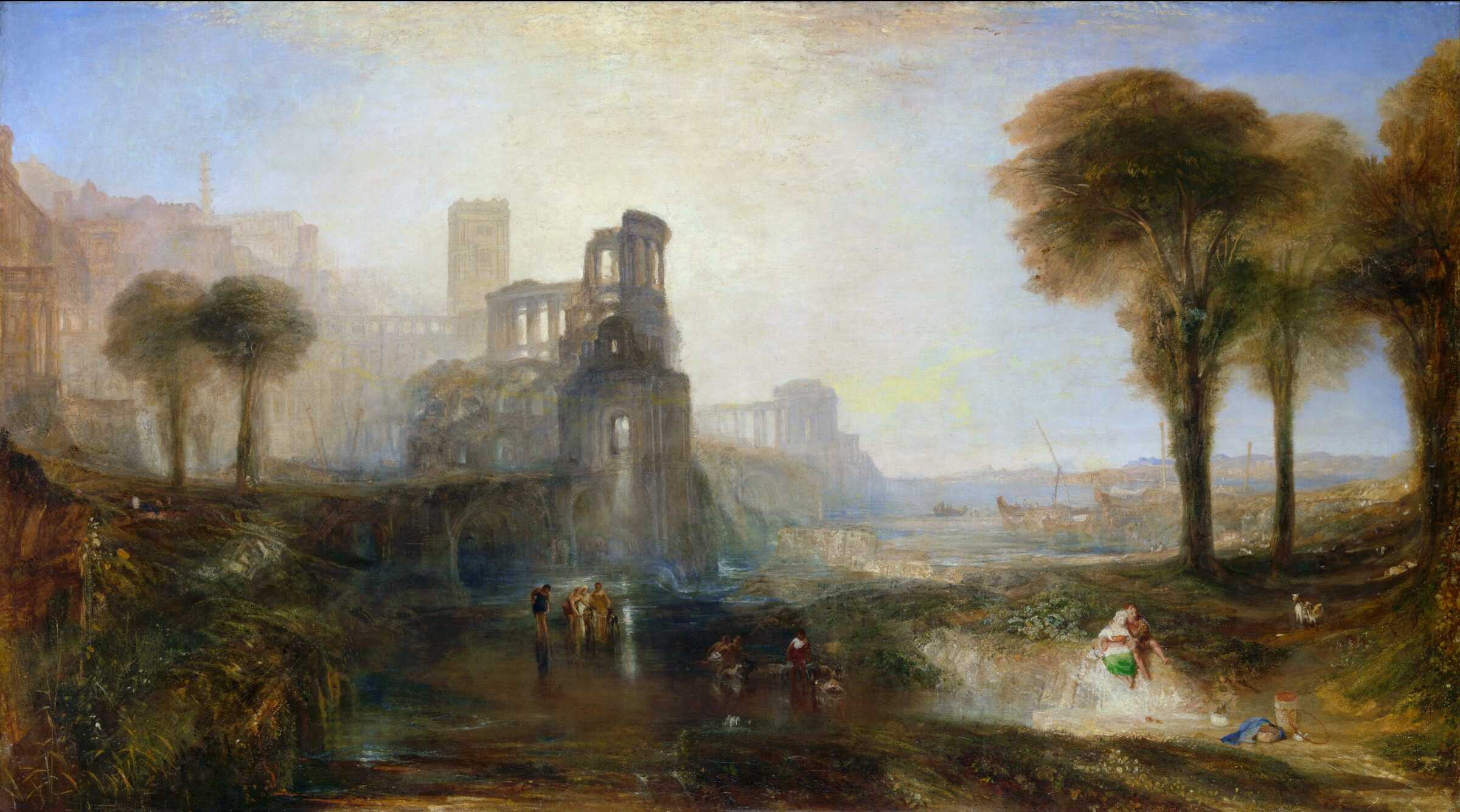

Image #1: Joseph Mallord William Turner’s painting of Caligula’s Palace and Bridge in Baiae. Credits: Gandalf's Gallery, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Image #2: A painting by Joseph Mallord William Turner, depicting the Bay of Baiae, with Apollo and the Sibyl. Public domain

The Bathhouse as a Stage

The chamber itself, the laconicum, was an architectural marvel. Heated by a hypocaust system, it allowed air to circulate beneath the floor and up through terracotta flues in the walls. Roman engineers created an atmosphere of controlled heat, dry and penetrating, designed to open the pores and cleanse the body. Mosaics on the floor provided both beauty and grip, while the suspended pilae created a miniature underworld where slaves stoked fires day and night.

This was not the rough bath of a soldier, nor the grand frigidarium of Caracalla’s later baths. It was an intimate, villa-sized chamber for private comfort, refinement, and display. Cicero, if indeed this was his, would have stepped from his study — where he drafted speeches against Antony or mused on the Republic — straight into a heated sanctuary designed for bodily ease.

The irony is not in the technology, which Romans prized as part of civilized life, but in the location. A bath at Tusculum could be restorative. A bath at Baiae — the city of vice — carried an entirely different resonance.

Divers in the Bath of Cicero in Baiae. Credits: Parco Archeologico Campi Flegrei, naumacos

Virtue on the Shoreline

Cicero himself acknowledged the temptations of leisure. In his letters, he often contrasted otium (rest, leisure) with negotium (public business). For him, otium was acceptable when filled with study and philosophy, dangerous when filled with indulgence. In De Officiis (3.1), he cautioned that:

“nothing is more shameful than to take delight in pleasure when the state is in distress.”

And yet, Cicero’s presence at Baiae suggests he lived this tension in real time. He may well have justified his villa as a place to write, to correspond, and to host select guests. He did draft philosophical works in his retreats. But to own property in Baiae — to have a sweating room there — was to place himself amid the very associations of corruption he condemned in principle.

It was a delicate balancing act. The Roman elite often accused one another of indulgence as a political weapon. Luxury was not just a lifestyle choice but a moral category, one that defined fitness for office. Cicero himself deployed it in his prosecution of Catiline’s followers. If his own villa strayed close to indulgence, it exposed him to the same charge.

The Literature of Hypocrisy

Seneca’s attacks on Baiae sharpen the irony further. He wrote (Epistle 51):

“If you are wise, you will avoid all resorts which invite a multitude of people… there is no retreat at Baiae, for luxury is never far away.”

Reading that line with Cicero’s name attached to the town feels like a dagger.

A statue of Cicero at the Ashmolean Oxford. Credits: Les Haines, CC BY 2.0

Juvenal, sarcastic and biting, linked Baiae with women of fortune and political manipulation, where senators “melted in baths” while Rome’s business was neglected. Propertius went further, casting Baiae as lethal to chastity:

“Baiae […] that shore fatal to chaste girls”

Elegies, (1.11.27)

For him, the place itself corrupted. All three authors painted Baiae as the antithesis of civic virtue. To stand Cicero in that frame is to see him through their eyes — not as a philosopher in his study, but as a senator in hot water, literally and figuratively.

Archaeology Meets Irony

The find also deepens our understanding of Baiae’s physical culture. Submerged structures show how private villas mimicked the grandeur of public baths, bringing hypocaust engineering into personal leisure. The new discovery joins the long list of Baiae’s submerged marvels: mosaic-lined nymphaea, colonnaded courtyards, private harbors cut straight into the rock.

For archaeologists, every find is another piece of the puzzle — proof of Baiae’s fusion of engineering brilliance and decadent purpose. But for cultural historians, attaching Cicero’s name adds a twist. It forces us to reckon not just with mosaics and mortar, but with moral texts and irony.

Mosaic detail in the Bath of Cicero in Baiae. Credits: Parco Archeologico Campi Flegrei, Nuccia Filomena Lucci

Cicero in Hot Water and Why This Discovery Matters

If confirmed, the bathhouse becomes a symbol of the contradictions that ran through Cicero’s life. He championed the Republic yet compromised with strongmen. He preached temperance yet lived amid luxury. He exalted virtue above pleasure yet owned a sweating chamber in the most notorious pleasure town in Italy.

The discovery does not reduce Cicero’s moral writings to hypocrisy. Instead, it makes them more human. Roman virtue was never a matter of flawless consistency but of negotiation between ideals and circumstances. Cicero in Baiae is Cicero as Roman: moralist and man, philosopher and property-owner, balancing virtus against the pull of otium in a place that symbolized the tension between the two.

The underwater bathhouse at Baiae is not just an archaeological curiosity. It is a reminder that moral philosophy is always tested against life itself. Cicero, who urged his son to prize virtue above all, also needed respite, warmth, and retreat. That he found it in Baiae, of all places, is a historical irony too sharp to ignore.

As archaeologists brush away the silt of centuries, they reveal not just tesserae and marble but the contradictions of Rome’s greatest voices. The Stoic in the sauna, the prophet of duty in the harbor of vice — Cicero’s bathhouse captures the essence of Roman life, where ideals and indulgence always mingled in uneasy steam.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: