Spartacus: The Gladiator Who Defied Rome

Who was Spartacus beyond the legend? Was he a visionary freedom fighter, or simply a desperate man driven by the brutal realities of slavery? A tale of courage, ambition, and the unrelenting human spirit that continues to captivate imaginations two millennia later.

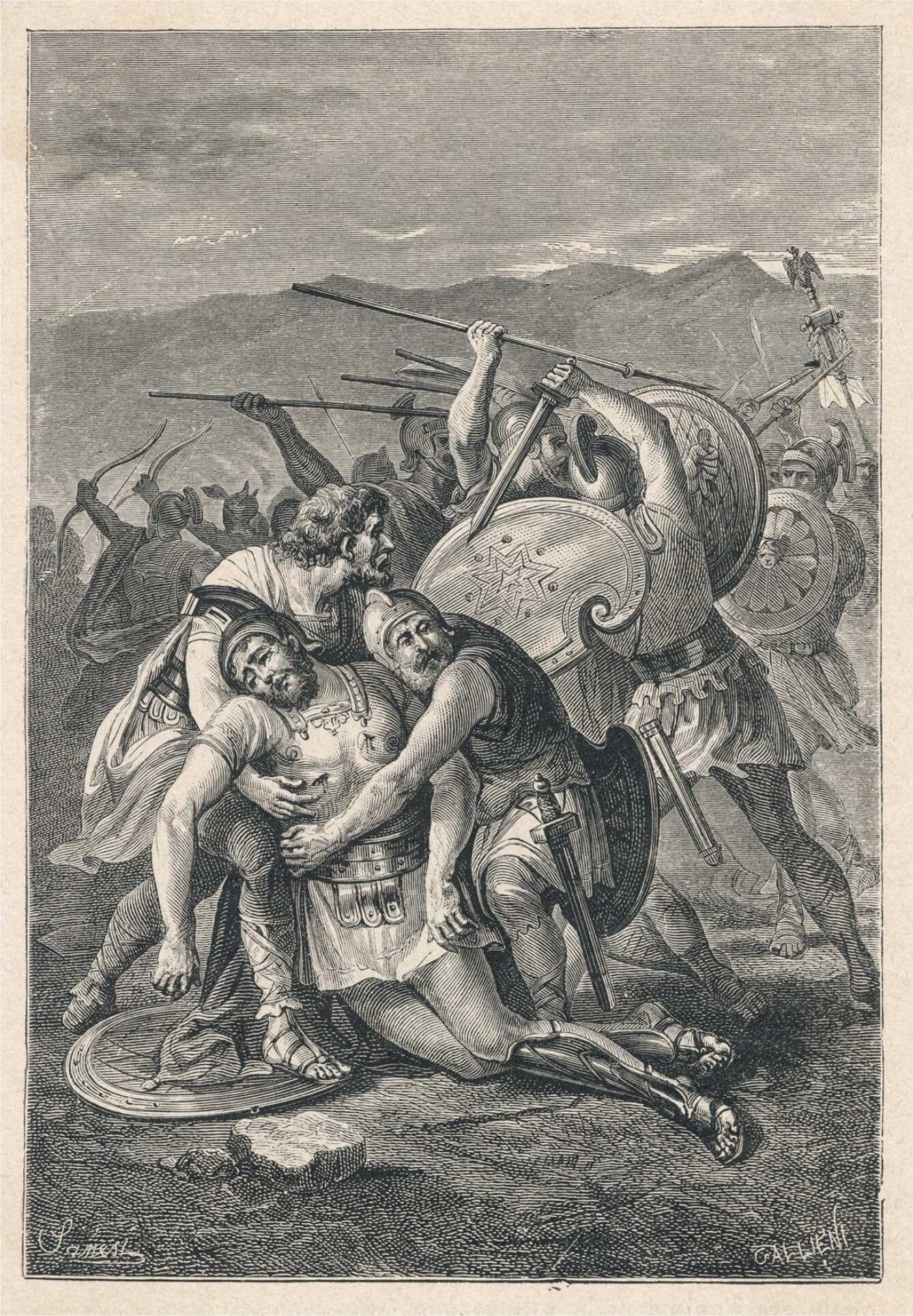

In the heart of the Roman Republic, where gladiators bled for spectacle and slaves toiled for the empire’s grandeur, one man dared to defy the might of Rome. Spartacus, a Thracian warrior turned slave, rose from the obscurity of a gladiator school to become the leader of one of the most audacious rebellions in history. His name, once whispered in fear by Roman patricians, has echoed through the centuries as a symbol of resistance against oppression.

Who was Spartacus?

Spartacus, whose early life remains shrouded in mystery, is believed to have been born in Thrace (present-day Bulgaria or a neighboring region) around 111–109 BCE. Historians speculate that he may have once served as a soldier in the Roman army before being captured and enslaved. His training as a gladiator in Capua, one of the most notorious gladiatorial schools in Italy, set the stage for what would become one of the most significant uprisings against the Roman Empire.

The details of Spartacus's early life remain largely unknown, a situation that's not unexpected considering his status as a slave in Roman society. Nonetheless, historical accounts of the Third Servile War do offer some insights, though they often present conflicting information. For example, Plutarch identifies Spartacus as originating from Thracian origins, specifically from Nomadic or possibly Maedic backgrounds — a Thracian tribe — depending on the manuscript interpretation.

Despite this, Plutarch acknowledges Spartacus as wise and brave, attributing to him qualities and a temperament more akin to a Greek (Hellene) than to a Thracian:

"The rising of the gladiators and their devastation of Italy, which is generally known as the war of Spartacus, began as follows.

A man called Lentulus Batiatus had an establishment for gladiators at Capua. Most of them were Gauls and Thracians. They had done nothing wrong, but, simply because of the cruelty of their owner, were kept in close confinement until the time came for them to engage in combat.

Two hundred of them planned to escape, but their plan was betrayed and only seventy-eight, who realized this, managed to act in time and get away, armed with choppers and spits which they seized from some cookhouse.

On the road they came across some wagons which were carrying arms for gladiators to another city, and they took these arms for their own use.

They then occupied a strong position and elected three leaders. The first of these was Spartacus.

He was a Thracian from the nomadic tribes and not only had a great spirit and great physical strength, but was, much more than one would expect from his condition, most intelligent and cultured, being more like a Greek than a Thracian."

Plutarch, Life of Crassus

Similarly, the historian Florus gives a similar version of the story:

"Spartacus, Crixus and Oenomaus, breaking out of the gladiatorial school of Lentulus with thirty or rather more men of the same occupation, escaped from Capua.

When, by summoning the slaves to their standard, they had quickly collected more than 10,000 adherents, these men, who had been originally content merely to have escaped, soon began to wish to take their revenge also.

The first position which attracted them (a suitable one for such ravening monsters) was Mt. Vesuvius.

Being besieged here by Clodius Glabrus, they slid by means of ropes made of vine-twigs through a passage in the hollow of the mountain down into its very depths, and issuing forth by a hidden exit, seized the camp of he general by a sudden attack which he never expected."

Publius Annius Florus, Epitome

In ancient times, the Thracians occupied extensive areas of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, predominantly across the Balkan region and parts of Asia Minor. Positioned outside the conventional boundaries of the Greco-Roman world, they were typically perceived as formidable fighters, yet were regarded as uncivilized from a cultural standpoint.

Living the Life of a Gladiator

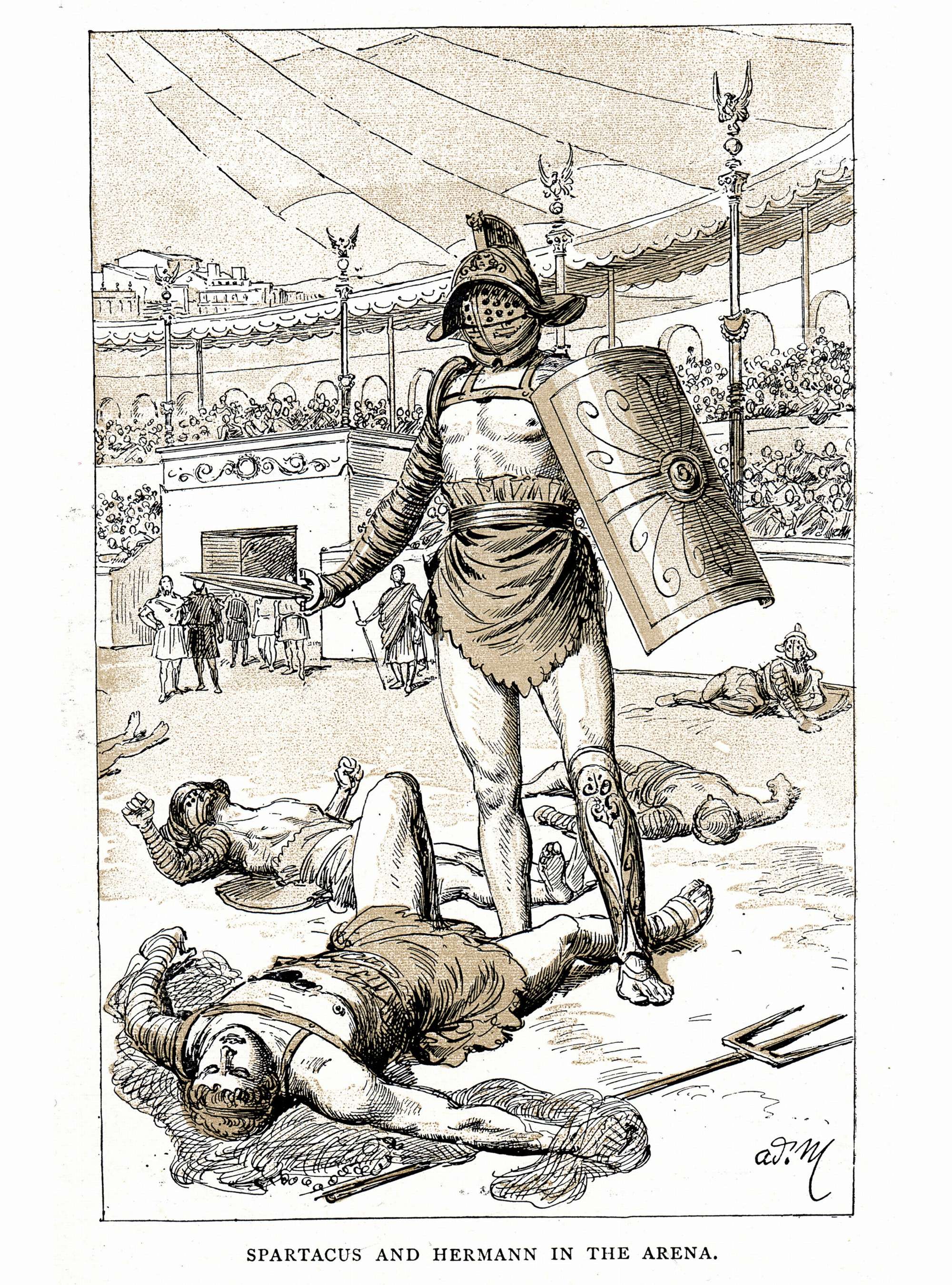

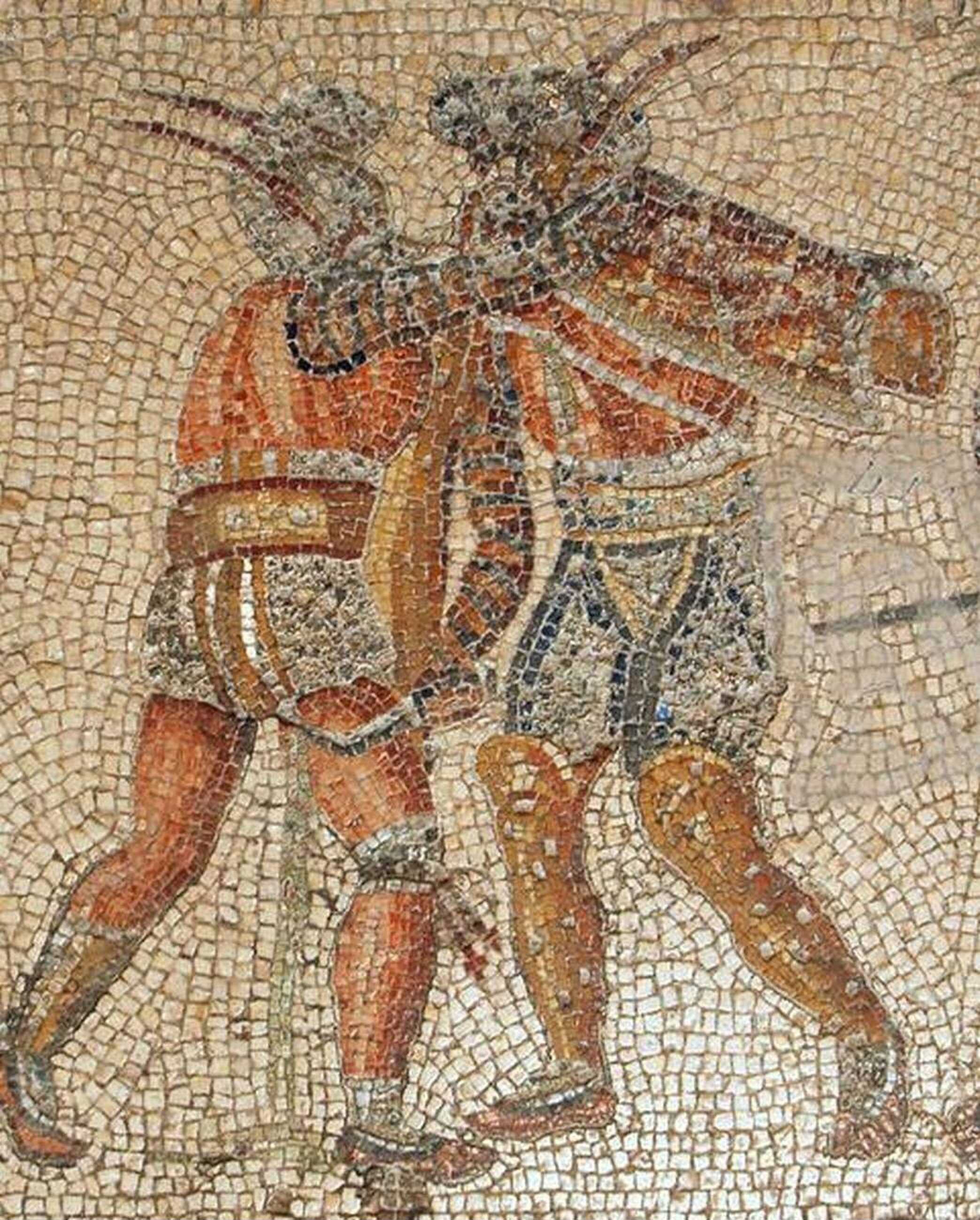

Gladiators were iconic figures of Roman entertainment, captivating audiences with their battles to the death from the Republic era until the early Christian empire's 5th-century ban on the games. While their exact origins are debated, with many historians suggesting they began in Campania, the widespread presence of amphitheaters throughout the empire serves as evidence of the gladiatorial games' widespread appeal.

The initial categories of gladiators were designated based on the adversaries of the early Roman state, including the Samnite, Gaul (which was later changed to murmillo), and Thracian fighters.

Gladiators were men specifically trained to fight with swords (gladii) and other weapons, often battling to wound or kill each other for the entertainment of spectators. Alongside them were other armed performers, such as beast fighters (bestiarii) and hunters (venatores), who were trained to hunt wild animals like leopards and bears for the amusement of large crowds.

Gladiatorial games became a hallmark of Roman culture as it evolved during the third and second centuries B.C., reaching their most intense development in the Campania region, south of Rome. This area, particularly the affluent city of Capua, served as a hub for gladiatorial schools and training facilities. Evidence of this culture is well-preserved in Pompeii, located about forty-five miles from Capua, where notices for gladiatorial performances have been found.

Gladiators were often forced into their violent profession, with many being condemned criminals or enslaved individuals who had little say in their fate. Trained to expertly wield weapons and inflict harm, they were both highly skilled and potentially dangerous, necessitating strict supervision. Some of them, resisted their grim destinies, going so far as to take their own lives rather than face the arena.

Others, however, were exploited beyond the arena, serving as enforcers or assassins for powerful Romans seeking to further their agendas. In times of political turmoil or civil unrest, gladiators posed a unique and constant threat to the stability of the Roman state. ("Spartacus And The Slave Wars A Brief History With Documents" by Brent Shaw)

Regardless of his precise background, Spartacus is recorded to have been captured by Roman forces. Subsequently enslaved, he was turned into a gladiator, receiving his training at a ludus located near Capua, a facility owned by Lentulus Batiatus. Presently, this city is noted for the remnants of its amphitheater, which is second in size only to Rome's Colosseum.

Notably, the details of Spartacus's background seemed of minimal importance, as the Thracian was trained as a murmillo, indicating a level of flexibility in the roles assigned within the gladiatorial system.

The Spark of Rebellion

The conspiracy led by Spartacus and his fellow gladiators took shape in 73 BCE at Capua, involving approximately 70 slaves. They managed to break free from the ludus, overcoming several pursuing soldiers, swiftly gathering supplies, and amassing additional supporters (it is estimated that there were 90,000 to 100,000 men in all) from the surrounding region.

Seeking a strategic advantage, they retreated to a defensible position on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, where Spartacus was unanimously chosen as their commander. This marked the onset of the Third Servile War.

The Fight for Freedom

Under Spartacus's leadership, the rebel army won multiple engagements against Roman forces. They even managed to defeat two consular armies, showcasing the seriousness of their challenge to Roman authority. Spartacus's ultimate goal, however, remains a subject of debate among historians. Some suggest he aimed to march on Rome itself, while others believe he sought to disperse his followers to their homes or to safer lands.

In the latter part of 73 BCE, the Roman government sent Praetor Gaius Claudius Glaber to quell the rebellion led by Spartacus. Commanding a hastily gathered force of about 3,000, Glaber attempted to encircle the rebels on Mount Vesuvius.

However, he underestimated the resourcefulness of Spartacus and his followers, who managed to descend the mountain using ropes to surprise and defeat the Roman troops. This victory significantly boosted the morale of Spartacus's forces. Shortly afterward, they overcame a second Roman detachment under Praetor Publius Varinius, prompting an influx of new recruits to their cause.

The situation reached a critical point for Rome in 72 BCE when the Senate, disturbed by the consecutive defeats, dispatched two consular armies led by Lucius Gellius and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus. Initially, these forces seemed to turn the tide by killing 30,000 rebels, including Spartacus's deputy, Crixus, near Mount Garganus.

However, historical accounts from Appian and Plutarch diverge at this juncture, with Appian providing a more dramatic account. According to him, Spartacus avenged Crixus's death by executing 300 Roman prisoners after defeating Lentulus's troops. Spartacus then faced the consular armies again in the Battle of Picenum, securing another significant victory for the rebels.

The Fall of the Rebellion

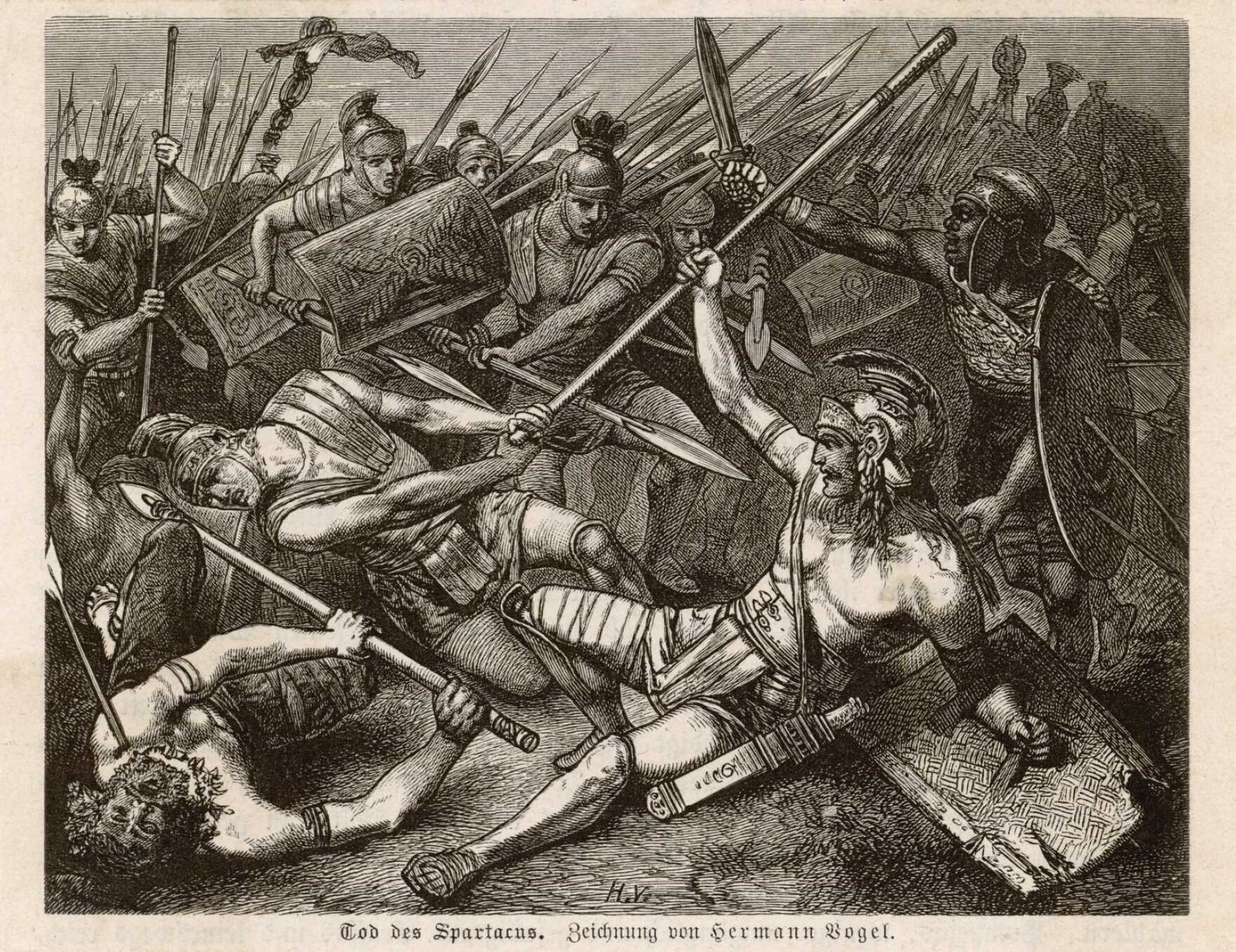

In 71 BCE, as Spartacus and his army headed south, their actions significantly alarmed the Roman Senate, prompting a more severe reaction. Marcus Licinius Crassus, known for his role in the Civil Wars on the side of Sulla, was tasked with quelling the Third Servile War.

Awarded a praetorship and command of six legions, along with the forces previously led by Gellius and Lentulus, Crassus assembled a formidable force of approximately 40,000 soldiers to confront the slave uprising. From their initial encounter near Samnium, as recounted by Appian, it was evident that Spartacus's forces were at a disadvantage, suffering a heavy loss of about 6,000 men.

Subsequent battles consistently favored Crassus, progressively pushing the rebels further south. A desperate attempt by Spartacus to escape to Sicily with the aid of Cilician pirates fell through due to betrayal, exacerbating the rebels' dire situation.

The situation for Spartacus and his forces grew even more precarious with the return of Pompey the Great to Italy. Pompey, renowned for his victories on behalf of Sulla's faction, had just successfully suppressed a revolt in Hispania led by Quintus Sertorius. With Pompey's arrival imminent, Crassus was under pressure to conclude the conflict swiftly to secure the triumph over Spartacus for himself, rather than share or lose the accolade to Pompey.

After Crassus rejected their attempts at negotiation, Spartacus and his followers were forced into a decisive confrontation at the Silarius River in 71 BCE. This final battle proved too overwhelming for the rebels, resulting in their defeat by Crassus's forces.

Spartacus met his end alongside thousands of his troops in the conflict at the Silarius River, with his remains never identified among the casualties. Numerous survivors attempted to escape the site of their defeat, yet Crassus's forces relentlessly pursued them.

The conclusive, grim chapter of the uprising unfolded along the Via Appia, where Crassus displayed a ruthless symbol of deterrence; approximately 6,000 captives taken by his legions were crucified and displayed along the roadside. This chilling spectacle served as a stark warning against defying Roman power.

Spartacus and the Last Great Slave War: Resistance and Legend

As already mentioned above what initially started in the summer of 73 B.C. as a violent slave uprising in Italy, eventually marked the beginning of a brutal two-year conflict. According to accounts, the rebellion began when seventy gladiator slaves escaped from the training school in the affluent city of Capua, located approximately 125 miles south of Rome.

This initial act of defiance rapidly escalated into a large-scale revolt, with tens of thousands of slaves joining forces to resist their masters and fight for their freedom from the oppressive conditions of servitude. While the brutality of this war is often compared to the savagery of the civil wars that Rome endured in the preceding decade, its impact was uniquely profound.

The battles, ambushes, and skirmishes waged by the rebellious slaves have secured this conflict's place as one of history’s most significant wars of resistance against slavery and as the most famous slave war in the ancient world.

This rebellion, led by Spartacus and other enslaved leaders was not the first to happen, but the last in a series of three major slave wars that Rome faced between the 130s and 70s B.C. The two earlier revolts occurred on the island of Sicily, Rome's first overseas province. The first Sicilian slave war (135–132 B.C.) and the second (104–100 B.C.) were both led by charismatic figures—Eunus and Kleon in the first, and Athenion and Salvias in the second.

The final war, centered in southern Italy, began in 73 B.C. Spartacus emerged as the most prominent leader of this rebellion, but he was only one of many enslaved individuals involved in the initial revolt.

Today, Spartacus has become a symbol of defiance against oppression, immortalized in Howard Fast's 1951 novel Spartacus and the 1960 film adaptation. However, the iconic status he enjoys today raises complex questions about the actual events of the slave wars, the myths that have surrounded him over time, and the reliability of the historical sources that document his story. (Spartacus And The Slave Wars A Brief History With Documents, by Brent Shaw)

The Man, the Myth, the Symbol

The Ancient Perspective: A Rebel of His Time

From the earliest accounts of Spartacus, ancient historians like Appian and Plutarch framed him as an extraordinary figure. While Appian emphasized the military genius of the rebel leader, capable of challenging the Roman legions, Plutarch presented him as a man of noble character who rose above his station.

These accounts, however, were not mere historical records. They were shaped by the political and social concerns of their time, using Spartacus as an exemplum—a moral or political example to warn against or inspire action.

Spartacus ballet performance, at Bolshoi in Moskow October 2013 (Michail Lobukhin, Anna Nikulina). Credits: Bengt Nyman, CC BY 2.0

In Roman discourse, Spartacus symbolized both the threat of rebellion and the resilience of Roman authority. His victories against Roman forces were portrayed as a cautionary tale of what could happen if Rome's societal order were undermined.

Yet, his defeat also underscored the ultimate supremacy of the state. For Romans, Spartacus was not just a historical figure but a rhetorical tool, a way to illustrate both the dangers of disobedience and the strength of Roman governance.

A Modern Revolution: Spartacus Reimagined

Centuries later, Spartacus emerged not just as a historical rebel but as a symbol of resistance against oppression. The modern era, particularly the 19th and 20th centuries, saw a wave of reinterpretations that infused Spartacus with revolutionary ideals.

Writers like Karl Marx and later socialist thinkers adopted Spartacus as a symbol of the proletariat rising against oppressive elites. His struggle was no longer merely about escaping slavery; it became a metaphor for systemic resistance against economic and social inequalities.

Howard Fast’s 1951 novel Spartacus and Stanley Kubrick’s 1960 film epitomized this shift. In these works, Spartacus transcends his historical context to become a universal emblem of freedom and human dignity:

- Fast’s novel explicitly connects Spartacus’s struggle with the broader fight against tyranny, positioning him as a figure of timeless relevance.

- Kubrick’s film amplified this theme, turning him into a cinematic icon of rebellion whose cry for liberty resonated with audiences during the Cold War and civil rights movements.

A Tool for Ideologies

The figure of Spartacus has been invoked repeatedly in political discourse. During the French Revolution, François-Noël Babeuf, who called himself "Gracchus Babeuf," adopted Spartacus as a symbol of his revolutionary ideology, advocating for the abolition of private property and equality for all—a vision he himself likely never held.

In Ireland, he became a symbol of resistance against British imperialism, reflecting the adaptability of his narrative to different cultural and historical contexts. Historian Saskia T. Roselaar cautions against over-romanticizing him as a proto-socialist revolutionary. She writes:

“Modern Marxist websites... present Tiberius [Gracchus] as a popular champion in the same vein as later Marxist or communist activists, although scholarship does not support this interpretation.”

The same could be said of Spartacus. While he undeniably stood against oppression, his primary aim was personal freedom and the survival of his followers, not the restructuring of society.

An Eternal Symbol of Resistance

What makes Spartacus so enduring is his ability to transcend time and place. As Benjamin Howland argues, the Thracian gladiator has become an "empty signifier," a figure whose meaning shifts based on the needs of those invoking him. Whether as a fearsome enemy of Rome, a champion of the oppressed, or a cinematic hero, Spartacus remains a powerful symbol of resistance.

His story, although firmly rooted in antiquity, continues to inspire and provoke. The tale of a man who dared to defy the greatest empire of his age resonates with universal themes of freedom, dignity, and the human spirit's resilience.

For ancient Romans, he was a reminder of the fragile balance of their social order. For modern audiences, he is a beacon of hope, proof that even the most unlikely individuals can rise to challenge the forces of oppression. (The Exemplary Spartacus: Reception, Adaptation, and Reconstruction, by Benjamin Franklin Howland)

The Rebel Who Shook Rome

The Spartacus Rebellion remains one of the most captivating and studied events in Roman history. From its beginnings as a gladiatorial escape to its evolution into a widespread uprising, the rebellion has drawn the attention of thinkers like Karl Marx, scholars, and even young students fascinated by its dramatic narrative.

Yet, one of the most significant misconceptions about this revolt is the idea that it was solely a slave uprising aimed at abolishing slavery.

A statue of Spartacus by Denis Foyatier, in the Louvre. Credits: Gautier Poupeau, CC BY 2.0

While Spartacus' escape from gladiatorial slavery created an inspiring narrative, the rebellion’s true uniqueness lies in the participation of free men alongside enslaved and freed individuals. Ancient records, particularly those from Appian, explicitly mention that:

“fugitive slaves and even some free men from the surrounding countryside...”

...joined Spartacus’ forces at Mount Vesuvius. This mix of classes not only amplified the threat posed by the rebellion but also revealed the underlying social and economic discontent of the Roman lower classes. To fully appreciate the Spartacus Rebellion, we must examine it as a revolt that transcended the boundaries of slavery and included free men seeking their own forms of change.

Unlike earlier slave uprisings, such as those in Sicily, Spartacus’ revolt posed an unprecedented threat. Ancient historians noted that the rebellion’s strength lay not just in its size but also in its ability to defeat Roman legions in open battle. This feat could not have been achieved by untrained rural slaves alone. As Appian recorded, the Italians:

“had sided with the gladiator Spartacus against the Romans, even though he was a wholly disreputable person.”

Many of these Italians were likely veterans of the Social War, bringing with them military expertise and a desire for political and social change rather than mere survival. The motivations of these free men were complex. Disillusioned by Rome’s unyielding oligarchy and their exclusion from meaningful political participation, many Italian veterans found themselves struggling economically, unable to compete with wealthy landowners.

When the Spartacus Rebellion arose, it offered not just a chance to resist oppression but also an opportunity to challenge the Roman elite and their control over the Republic. This fear of social upheaval, more than the physical proximity of Spartacus’ forces to Rome, is what terrified the Roman aristocracy. As Plutarch observed, the Senate was:

“moved by fear and the danger...”

...of the revolt and responded with exceptional force, dispatching both consuls and eventually Crassus and Pompey to suppress it.

Despite its revolutionary elements, the Spartacus Rebellion was not a Marxist-style proletarian uprising. Marxist historians have often imbued Spartacus with ideals of class struggle, but as Roselaar (a prominent scholar specializing in Roman economic history) explains, “works by Marxist ancient historians indeed sometimes take this line,” although “scholarship does not support this interpretation.”

Instead, the rebellion was a coalition of diverse agendas: Spartacus sought to return to Thrace, while his followers—free men, ex-soldiers, and displaced peasants—had their own ambitions for status, power, and economic security.

The Spartacus Rebellion was a unique historical phenomenon, blending elements of a slave revolt with the political aspirations of free men. It highlighted the growing divisions within Roman society and foreshadowed the civil unrest that would eventually lead to the Republic’s collapse.

Though not the Marxist hero he is sometimes portrayed to be, Spartacus remains an enduring symbol of resistance against oppression and a figure whose rebellion forever altered Rome’s history. (The Spartacus Rebellion, More Than a Slave Revolt The Spartacus Rebellion, More Than a Slave Revolt, by Gavin J. Maziarz. Gettysburg College)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: